Framing Regent Park: The National Film Board and the construction of “outcast spaces” in the inner city – 1953 & 1994

Please note: I’ve included this post in the Category that deals with Malcolm Campbell High School Stories (Before & After) as it concerns a particular way of seeing the world, that was prevalent in Canada in the 1950s.

[End of note]

Sean Purdy’s article, “Framing Regent Park: The National Film Board and the construction of ‘outcast spaces’ in the inner city, 1953 and 1994,” appears in Home, work, and play: Situating Canadian social history (2010).

The article was first presented at the International Geographical Union Conference, Commission on the Cultural Approach in Geography, Rio de Janeiro, June 2003. It discusses two National Film Board documentaries about the Regent Park housing project in Toronto.

A Farewell to Oak Street (1953)

The article has enhanced my understanding of the conceptual framework that drove documentary making at the film board starting in the 1950s.

Farewell to Oak Street, as Purdy notes, promoted the attitudes that were prevalent among urban planners in the 1950s.

Purdy remarks (p. 102) that the 1953 documentary employed “fictional vignettes of the ‘old’ and the joys of the ‘new’ juxtaposed throughout the film” to emphasize the contrast between what the film’s producer and writer viewed as “the physical and social depravity of the Cabbagetown slums and the modern promise of public housing.”

The film, in Purdy’s view, continued in the tradition of the war-time NFB founder, John Grierson, in crafting a “propaganda statement” about the value of public housing projects as they were viewed by urban planners in the 1950s.

As in what Purdy describes as the classic documentary film, the 1953 production “aimed to project a ‘generalized reality or social truth’ which, in the eyes of the filmmakers and contemporary reformers, consisted of the shameful contrast between the decrepit disorder of Cabbagetown and the efficiency of the new housing development.”

“Realist” vision

Purdy notes that despite its extensive use of fictionalized dramatic scenes, “it was crucial that the film convey an air of authenticity and realism. Each of the scenes was carefully crafted, acted, sequenced, and narrated to construct this ‘realist’ vision.

“Locations were used rather than studios; the majority of actors were either residents themselves or non-professionals, which was intended to drive home to the viewers that what they were seeing was the genuine thing; the voiceover narration by well-known veteran of CBC radio and later American television star, Lorne Greene, aimed to express the ‘authority’ of pro-urban renewal commentary” (pp. 102-103).

Women’s roles

Purdy adds (p. 104) that the film “especially accentuates women’s enhanced roles as mother and housewife. Yvonne Klein-Matthews has shown that NFB films of the 1940s-50s only validated women’s roles as mothers and housewives, celebrating their natural homemaking virtues and warning against the perils of joining the male-dominated workplace. Farewell to Oak Street was no exception.

“The flaking paint, grimy walls, filthy floors, and crowded rooms are distinguished conspicuously from the spacious rooms, new-fangled appliances, and hardwood floors of Regent Park. Domestic work by women is duly celebrated: ‘A great deal of washing and scrubbing goes on nowadays. The Maclean kitchen has a new modern look as do the MacLean ladies.’

“In Cabbagetown, on the other hand, ‘keeping clean was a daily battle and a lost cause.’ One dramatized scene shows a woman futilely attempting to kill a cockroach, expressing symbolically the frustration of women’s life within the slums.”

Disorder and confusion are represented in the slum housing by showing six separate families trying to use the same bathroom: “‘Things mislaid, everyone getting in everyone’s way.'”

Inner-city workers

The title of the article refers to the construction of “outcast spaces.” Purdy notes that “The NFB joined contemporary sociologists, social workers, and the media in contributing to the powerful stigmatization of inner-city workers.

“Even if the slum environment to itself was largely to blame in these accounts, working families and Cabbagetown were portrayed as dirty, disreputable, and prone to various pathologies, a condition only redeemed in the eyes of the national film agency and reformers by the top-down, modernization of urban renewal and public housing.

“Only public housing, moreover, could reinstall women in their valid roles as housekeepers and mothers, and families to their central role as the bedrock of society and nation.

“Children, too, would benefit from a safe and orderly setting within the home and the neighbourhood, free from the lures of delinquency and sex.

“The medium of film with a mass, popular audience was a convenient and effective means to get across this message of the urgent necessity of social engineering” (p. 104).

Return to Regent Park (1994)

Purdy also discusses (p. 105) a subsequent documentary made about Regent Park:

“Directed by Bey Wayman, the film was financed and produced by the NFB, Wayman’s Close-up Productions, and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), Canada’s public broadcasting network.

“It first aired on 6 May 1994 on CBC Newsworld’s Rough Cuts, a weekly program that brings new national and international documentaries to the small screen. We have no viewing figures for the documentary, but it has been replayed periodically on public television in Canada and is widely available in university, public, and community libraries.

“In 1995, and NFB head Sandra Macdonald told a federal parliamentary committee on Canadian Heritage that she was particularly proud of Weyman’s film. In her nationalistic vision of the NFB’s role, she opined that, “We dream of the day when … Central Park West [ a popular American show {the square brackets are included in the original quotation}] will be replaced by a broadcast of Return to Regent Park.”

Purdy notes that unlike its 1953 predecessor, the film provides room for some of the residents of Regent Park to discuss life in the housing project. As in the previous project, however, the film “sets out to engage in social criticism, directing its fire at the superblock public housing design that enclosed the project buildings within its own discrete borders.”

Voices of tenants

“While its techniques are more subtle and elegant,” notes Purdy, “the latter film also relies on the theme of the contrast between the ‘old’ and ‘new’ to tell its story.

“Reflecting a common technique in socially critical documentary filmmaking, it constantly juxtaposes interviews with talking heads and residents and shots of the project with old archival footage from newsreels, television, and Farewell to Oak Street itself, contrasting the overly optimistic and top-down planning of the 1940s-50s urban reformers with the drug and crime problems in the project today and the efforts of activists to sell a physical redevelopment plan to the city of Toronto” (p. 106).

Purdy notes that the 1994 version offers a “less preachy” look at Regent Park than the 1953 version. He views the inclusion of the voices of tenants as a welcome addition.

However, Purdy adds, the film “also (unintentionally) produces a damning characterization of the homes, neighbourhood, and residents of Regent Park by what it focuses on and what it omits. Drugs and crime, for example, are not discussed in any kind of social or historical context. As in its predecessor, the viewer gets little sense of the whys.”

Social geography

“Why,” asks Purdy, “are public housing residents so poor? Why does Regent Park have a drug problem? Many of the socio-economic and ideological developments that have shaped material misery and driven a minority of residents to drug dealing and anti-social behaviour in public housing are never discussed in the film. Yet it is in this context of bitter despair that we need to place the widely publicized rise in violence and drugs in the project and elsewhere in the 1990s.”

Purdy lists other topics that warrant inclusion. These include the findings of social geographers, the history of tensions between black tenants and the police which has centred on allegations of police brutality and other forms of “racialized” policing, and the role of new “experts” who have appeared on the scene since the 1950s.

By way of conclusion, Purdy notes (pp. 109-110) that the second documentary’s “steadfast concentration on the physical design deficiencies of the project provides only a very partial understanding of the problems that tenants face.

“Lacking any sense of social, economic, and political context concerning why Regent Park and its residents were territorially stigmatized, the documentary leaves the viewer with the impression that marginalization stems largely from the individual problems of tenants themselves.

“Moreover, we get little indication in the film that tenants contested this stigmatization in various ways. The film, therefore, unwittingly assists in the social construction of the project as an ‘outcast space’, contributing to the damning social and economic exclusion faced by project dwellers.”

By way of an update, the following post is also of relevance:

A May 10, 2015 New York Times article is entitled: “The Real Problem With America’s Inner Cities.”

Click here to access excerpts from the latter article >

Recent media reports and a 2010 Master’s thesis

A Dec. 5, 2012 Toronto Star article about a documentary dealing with America’s failed drug war is of relevance with regard to topics discussed in this blog post.

A Nov. 16, 2010 article in The Globe and Mail provides an overview of views regarding the redevelopment of Regent Park.

A June 16, 2012 Toronto Star article addresses the same topic.

A Dec. 27, 2012 Globe and Mail article discusses development in the Corktown neighbourhood south of Regent Park.

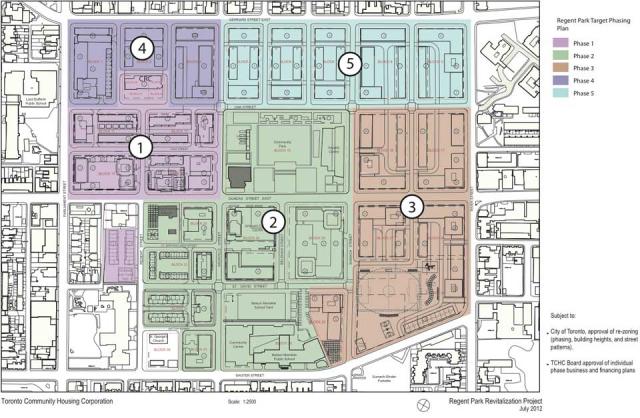

Map showing the planned phases of redevelopment, image courtesy of TCHC. This image has been downloaded from http://urbantoronto.ca/news/2012/09/tchc-and-daniels-unveil-plans-phase-three-regent-park-revitalization

An Sept. 12, 2012 article at the urbantoronto.ca website, TCHC and Daniels Unveil Plans for Phase Three of the Regent Park Revitalization, provides an overview of current projects at Regent Park.

A Sept. 12, 2012 Canadian Press article posted at the CBC website speaks of the same projects. CBC Radio’s Metro Morning has also posted a series of blog posts concerned with the redevelopment of Regent Park.

Social spaces

A September 2011 Master of Arts thesis by Astrid Greaves of Queen’s University offers a sociological perspective on revitalization projects at Regent Park. The thesis is entitled Urban regeneration in Toronto: Rebuilding the social in Regent Park.

In her concluding paragraph, Greaves comments:

“As I have investigated throughout this thesis, design can only ever offer a partial account of the forces that make up social spaces. With the influence of social, political and economic factors, as well as materials, documents and the actual usage, what is the role of the designer?

“This research raises questions regarding popular understandings of the role of urban designers in contemporary Toronto. How can urban designers accommodate the plethora of different phenomena involved within urban spaces? Does the knowledge of these other influences necessitate a shift in the practices of urban design?

“Perhaps we need to recognize the significant influence that these different factors play, and move away from the notion that effective or progressive social change can be ‘planned’ or ‘designed’ in any definitive sense.”

Additional planning and research documents related to Regent Park include:

A paper entitled Lessons from St. Lawrence for the Regent Park redevelopment process (2003)

City of Toronto – Regent Park – Community Facilities Strategy, 2005

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!