We have a white extremism problem, Doug Saunders argues – Globe and Mail, Nov. 12, 2016

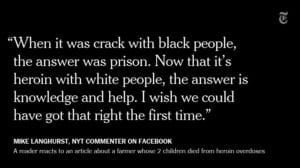

The image – click on it to enlarge it – is from a March 18, 2017 tweet from The New York Times @nytimes reading: Our top 10 comments of the week http://nyti.ms/2nD8BJX

Updates

A Nov. 14, 2016 CBC article is entitled: “Social media is blinding us to other points of view: Everyone saw a different reality during the U.S. election, depending on their own opinions.”

A Dec. 1, 2016 Guardian article is entitled: “Should we even go there? Historians on comparing fascism to Trumpism: Recent events around the world have prompted debate about the historical parallels between our times and the period preceding the second world war.”

A Dec. 13, 2016 Aeon article is entitled: “Why the Nazis studied American race laws for inspiration.”

A Dec. 14, 2016 Raw Story article is entitled: “A historian explains how Trump’s climate ‘hit list’ recalls ideology-driven science of Nazis and USSR.”

A Nov. 28, 2016 Quartz article is entitled: “A Yale history professor’s powerful, 20-point guide to defending democracy under a Trump presidency.”

Also of interest and relevance: White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide (2016)

As well: Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (2016)

A Jan. 4, 2017 Guardian article is entitled: “The Canada experiment: is this the world’s first ‘postnational’ country?: When Justin Trudeau said ‘there is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada’, he was articulating a uniquely Canadian philosophy that some find bewildering, even reckless – but could represent a radical new model of nationhood.”

A recent study by Pankaj Mishra is entitled: Age of Anger: A History of the Present (2017).

A Feb. 27, 2017 Guardian article is entitled: “‘Angry white men’: the sociologist who studied Trump’s base before Trump: Michael Kimmel, one of the world’s foremost experts on masculinity, examines its role in men’s adherence to – and departure from – far-right movements.”

A March 3, 2017 Columbia Journalism Review article is entitled: “Study: Breitbart-led right-wing media ecosystem altered broader media agenda.”

A March 13, 2017 opendemocracy.net article is entitled: “Scorn wars: rural white people and us.”

A March 13, 2017 CityLab article is entitled: “Mapping the Achievement Gap: A colorful dot map reveals the stark differences in educational levels across urban and rural areas—as well as the effects of racial segregation within cities.”

A Best of 2016 Longreads article is entitled: “Who’s Been Seeding the Alt-Right? Follow the Money to Robert Mercer.

An April 13, 2017 Guardian article is entitled: “British spies were first to spot Trump team’s links with Russia: Exclusive: GCHQ is said to have alerted US agencies after becoming aware of contacts in 2015.”

An April 20, 2017 Institute for New Economic Thinking article is entitled: “America is Regressing into a Developing Nation for Most People: A new book by economist Peter Temin finds that the U.S. is no longer one country, but dividing into two separate economic and political worlds.”

A May 23, 2017 Stat News article is entitled: “Trump wasn’t always so linguistically challenged. What could explain the change?”

A May 23, 2017 Language Log article is entitled; “Donald Trump: Cognitive decline or TDS?”

A May 23, 2017 Guardian article is entitled; “Hiding in plain sight: how the ‘alt-right’ is weaponizing irony to spread fascism: Experts say the ‘alt-right’ have stormed mainstream consciousness by using ‘humor’ and ambiguity as tactics to wrong-foot their opponents.”

Also of relevance is a book I learned about from a New York Times article, namely Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (2017).

An Aug. 3, 2017 Dallas News article is entitled: “Tangled web connects Russian oligarch money to GOP campaigns.”

A May 8, 2018 New York Times article is entitled: “Why Are So Many Democracies Breaking Down?”

[End]

*

A Nov. 12, 2016 Globe and Mail article is entitled: “Whitewashed. The real reason Donald Trump got elected? We have a white extremism problem.”

The article is by Doug Saunders, The Globe and Mail’s international affairs columnist, whose Twitter handle is @DougSaunders

Previous posts about Nazi Germany, and about stereotyping, come to mind.

Ethnic exclusion

We are currently dealing, Saunders argues, with “themes of ethnic nationalism and racial and religious intolerance.”

The people who voted for Trump,” Saunders notes, “have developed a set of beliefs that have led them to see a sort of strongman nationalist politics of ethnic exclusion as being perfectly acceptable, only two generations after their country fought a global war against that very thing.”

Academic studies regarding populist and extremist movements

The article draws upon the work of several academics including Matthew Goodwin, a politics professor at the University of Kent who has studied white voter support for populist and extremist movements.

“Profiling white people who turn to political extremism, it turns out,” Saunders notes, “is not that different from the effort to profile Westerners who are vulnerable to Islamic extremism – and the two communities have some backgrounds in common.”

The article notes we are not dealing with matters of poverty or unemployment:

“Most Americans with incomes below $50,000, and a strong majority of people with incomes below $30,000, voted for Hillary Clinton. Mr. Trump got his strongest support from solidly middle-class white people with incomes from $50,000 to $100,000, and also won more support in higher-income groups.”

The article refers to research by Eric Kaufmann, a professor of politics at the University of London and author of The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America: The Decline of Dominant Ethnicity in the United States.

Gender not the key variable; size of community and education is

The article notes that gender was not as big an indicator as predicted:

“If poverty, gender and region don’t draw white people into extremism, what does? One factor is size of community: Americans who live in cities of 50,000 or more overwhelmingly voted for Ms. Clinton, by a margin of 59 to 35 per cent. But “small city or rural” residents voted for Mr. Trump by almost the same margin (62 to 34), with the suburbs almost equally split between the two. And the other big predictor, as the scholars noted, was education: White people without post-secondary education voted for Mr. Trump to a huge degree (70 per cent to 30); he also got the most votes from white people with degrees, but only by 4 per cent. And military service is a big predictor: Six veterans and soldiers in every 10 voted Trump (but this has always been true for Republicans).”

Channeling anger

Saunders argues that the above-noted predictors do not, however, explain “the source of their extremism, the factors that motivated them to take this controversial political leap, what has made them so angry, and what we might do to channel that rage into something less destructive.”

In his interviews with Trump supporters, which Saunders documents in his longread article, many respondents repeated a particular phrase, namely: “This doesn’t feel like my country any more.”

“He liked Trump, [one person who was interviewed] said, because he could restore the United States of his childhood. Things, he said, had kept getting worse, and he wanted someone to fix them.”

Doug Saunders add:

“And that sense of decline and pessimism is strictly a white phenomenon: Among racial minorities, six people in 10 feel that life has improved since the 1950s, as do people with postsecondary education. The belief that a golden age once existed, but has been trammelled and despoiled by racially different people, is a classic indicator of authoritarian instinct and susceptibility to extremism.”

Gated communities

Among the people that Saunders quotes in his article is a woman in Florida who lives in a gated community:

“Although her neighbourhood, which is gated and predominantly white, does not see much crime, her family had armed up, accumulating more firearms to protect itself. They spoke favourably of Donald Trump’s management acumen, and his ability to close the border and fix things.”

Halo effect, contact effect

The article refers to a phenomenon that has been called the “halo effect.” An online definition speaks of the halo effect as “the tendency for an impression created in one area to influence opinion in another area.”

“By contrast,” notes Saunders, “white people who live in areas where they’re immersed in longstanding populations of immigrants and minorities – that is, in big cities – don’t generally tend to vote for the politics of racial intolerance. That’s called the “contact effect” – you don’t get anxious about immigration if you live around immigrants. But people who live in mainly white areas that adjoin cities with greater diversity often show very high levels of support for people like Mr. Trump.”

Key identifier of an extremism-tolerant psychology

Saunders identifies a sentiment – “what many scholars regard as a key identifier of an extremism-tolerant psychology: a belief that social and political change – even if it is broadly beneficial – is to be feared and resisted, and that order, stability and authority are crucial to comfort and security.”

“Combine that with a sense of threatened ethnic identity and membership in a lower-education voting group,” notes Saunders, “and you have what Prof. Kaufmann and other scholars describe as the most potent recipe for support of authoritarianism.”

Carol Anderson, a historian at Emory University, is quoted: “You know, if you’ve always been privileged, equality begins to look like oppression. That’s part of what you’re seeing in terms of the [white] pessimism, particularly when the system gets defined as a zero-sum game – that you can only gain at somebody else’s loss.”

Two popular theories seeking to explain white extremism

The article refers to theories in two books seeking to explain features of American cultural politics:

Thomas Frank in his 2004 book, What’s the Matter With Kansas, argued that both political parties had abandoned the economic interests of blue-collar Americans in favour of cultural politics.

In Frank’s view, Saunders explains, “white voters had been distracted away from their dealing with their own economic concerns by a politics devoted to scapegoating minorities and immigrants.”

The second book referred to in the article is Hillbilly Elegy (2016), by J.D. Vance, “which describes poor working-class white communities (such as that of his own Appalachian family) as having become dependent on the state and unable to free themselves from this dependence because they’ve come to believe in a form of racially tinged conspiracy politics that blames anyone but themselves.”

Saunders concludes that “both books were shown by Mr. Trump’s victory to be somewhat misleading. In Mr. Vance’s case, the author himself proved to be much more typical of the Trump movement than the people he chronicled: It was the angry white voters who resent the hillbillies – people like Burt Weiss [one of the interview subjects in the article] – not the hillbillies themselves, who flocked to the Republican candidate. And contrary to Mr. Frank, the radical turn against racial minorities did not turn out to be a distraction from liberal economics; instead, Mr. Trump packaged protectionist, anti-trade messages with closed-border messages of nativism, making the economic and the ethnic equal parts of a far-right, isolationist agenda that captured the interest of a great many blue-collar and middle-class voters, as long as they were white.”

Distinction between perception and reality

In his concluding remarks, Saunders argues that “The propensity of white people to turn to radicalization does seem to be much more rooted in deep psychological anxieties than in anything material or economic.”

The article argues, in this context, that the Trump movement “is based on a deeper psychic sense of loss, one not so solidly moored in lived reality”:

“Carol Anderson, a historian at Atlanta’s Emory University who recently published the book-length study, White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of our Racial Divide, sees the turn toward Trumpian extremism as a psychological response among many white people not to any actual loss – the Trump voters are typically more well-off people, who have gained in recent years – but to a sense of relative loss of influence caused by the increasingly equal status of black and brown Americans.”

In Saunder’s view, “a psychology of wounded ethnic pride – and often of wounded virility – has overtaken a large part of the white community, and not generally the part that is actually feeling economic pain. If those of us worried about the extremists in our midst want to root them out and turn them around, we need to speak to this underlying sense of loss. It may not be rational or realistic, but it has become profound enough that it has provoked the most extreme and dangerous political event of the century.”

What to do?

The Nov. 12, 2016 Globe and Mail article argues that: “It is clear that economic solutions to the actual crises of the postindustrial white working class, however desirable they may be in their own right, are not going to solve the crisis of radicalization, which is rooted far more deeply in perception and context than in reality.”

Education and urban planning

More education might help, Saunders notes:

“It might be worth facing the problem directly: If the strongest predictors of white radicalization are a lack of postsecondary education and residence in an ethnically segregated non-urban community, it’s worth thinking of reducing the number of people who live this way.”

Urban planning might also help, Saunders asserts:

“Likewise,” the article concludes, “creating less-segregated, higher-population-density urban and suburban districts is a good idea in its own right, both ecologically and in planning terms (it makes public transit possible, for example); if it cuts down on pockets of racial intolerance, then it is doubly worth pursuing.”

Language of mainstream politics

The article also argues that conventional liberal and conservative parties will “need to start talking about our plural society differently.” Instead of celebrating “diversity,” this argument goes, “it may be better to focus on the other side of the immigration coin, the near-universal tendency of newcomers to adopt universal values, to become part of mainstream society, to intermarry, to become ‘normal'”.

“I think if you actually speak directly to the ethnic majority and their anxieties – if you point out the degree of assimilation that’s occurring, the extent to which people are becoming more like each other and their children are becoming just normal Americans, then white people may begin to see them as something other than a threat.”

Conclusion

“If they want to end this nightmare,” the article concludes, [mainstream politics] will need to find a way to reach 60 million radicalized white people and find words that can bring them back to earth.”

[End of overview]

Populism

On the topic of populism, a Feb. 3, 2017 fivethirtyeight.com article is entitled: “14 Versions Of Trump’s Presidency, From #MAGA To Impeachment.”

A Feb. 17, 2017 Columbia Journalism Review article is entitled: “What does Trump have in common with Hugo Chavez? A media strategy.”

A March 26, 2017 Guardian article is entitled: “Populism is the result of global economic failure: Political revolts are inevitable in a world where employees are wage slaves and bosses super rich.”

State propaganda and related topics

A 2016 RAND Corporation article is entitled: “The Russian ‘Firehose of Falsehood’ Propaganda Model: Why It Might Work and Options to Counter It.” You can find the article by pointing your browser to the above-noted title.

A March 27, 2017 Atlantic article is entitled: “How Right-Wing Media Saved Obamacare: Years of misleading coverage left viewers so misinformed that many were shocked when confronted with the actual costs of repeal.”

A March 29, 2017 Pew Research Center article is entitled: The Future of Free Speech, Trolls, Anonymity and Fake News Online: Many experts fear uncivil and manipulative behaviors on the internet will persist – and may get worse. This will lead to a splintering of social media into AI-patrolled and regulated ‘safe spaces’ separated from free-for-all zones. Some worry this will hurt the open exchange of ideas and compromise privacy.”

A March 30, 2017 Guardian article is entitled: “Russian deception influenced election due to Trump’s support, senators hear: Former FBI special agent discusses Russia’s longstanding ‘active measures’ – including the spread of fake news – before Senate intelligence committee.”

A July 18, 2017 Politico article is entitled: “How the GOP Became the Party of Putin: Republicans have sold their souls to Russia. And Trump isn’t the only reason why.”

Richard Rorty

A July 2017 Los Angeles Review of Books article is entitled: “Conversational Philosophy: A Forum on Richard Rorty.”

A May 11, 2017 Boston Review article is entitled: “Understanding Populist Challenges to the Global Order.”

In this post, I have referred to a book I learned about from a New York Times article, namely Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (2017).

Summary

How American race law provided a blueprint for Nazi Germany

Nazism triumphed in Germany during the high era of Jim Crow laws in the United States. Did the American regime of racial oppression in any way inspire the Nazis? The unsettling answer is yes. In Hitler’s American Model, James Whitman presents a detailed investigation of the American impact on the notorious Nuremberg Laws, the centerpiece anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi regime. Contrary to those who have insisted that there was no meaningful connection between American and German racial repression, Whitman demonstrates that the Nazis took a real, sustained, significant, and revealing interest in American race policies.

As Whitman shows, the Nuremberg Laws were crafted in an atmosphere of considerable attention to the precedents American race laws had to offer. German praise for American practices, already found in Hitler’s Mein Kampf, was continuous throughout the early 1930s, and the most radical Nazi lawyers were eager advocates of the use of American models. But while Jim Crow segregation was one aspect of American law that appealed to Nazi radicals, it was not the most consequential one. Rather, both American citizenship and antimiscegenation laws proved directly relevant to the two principal Nuremberg Laws–the Citizenship Law and the Blood Law. Whitman looks at the ultimate, ugly irony that when Nazis rejected American practices, it was sometimes not because they found them too enlightened, but too harsh.

Indelibly linking American race laws to the shaping of Nazi policies in Germany, Hitler’s American Model upends understandings of America’s influence on racist practices in the wider world.