Colonel Samuel Smith and his homestead: Speaking notes for October 2011 presentation

*

Update

An April 4, 2012 post is entitled:

The text for the 2011 Parkview School letter was developed with input from many sources

Click here for additional posts about Parkview School >

[End]

A 26-minute video based on a presentation by Jaan Pill at an October 4, 2011 meeting of the Long Branch Historical Society is available for viewing on Vimeo. The sale in late August 2011 of Parkview School was announced in the Toronto media including in a Sept. 1, 2011 Etobicoke Guardian article. Please note that the Smith house was demolished in 1955 – not in 1952 as the newspaper article in the link in the previous sentence erroneously asserts.

Below are speaking notes from the presentation.

Jaan Pill

October 4, 2011

Long Branch Historical Society

Long Branch Library

Colonel Samuel Smith and his homestead

I want to thank you for the opportunity to speak with you this evening.

View of Parkview School, photographed from top of Aquaview Condominiums, November 2012. Photo credit: Jaan Pill

As you may know, the archaeological remains of the Colonel Samuel Smith homestead are located under the school grounds of Parkview School at 85 Forty First Street near Lake Shore Blvd. West in Long Branch, in the City of Toronto.

As you may also know, the sale of Parkview School, by the Toronto District School Board to the French public school board Conseil scolaire Viamonde, closed on August 30, 2011.

We owe thanks to many public officials, including Etobicoke-Lakeshore MPP Laurel Broten and Ward 3, Etobicoke-Lakeshore Trustee Pamela Gough – as well as many area residents – for what has turned out to be a good news story regarding this school.

The closing of the sale means that Parkview School remains in public hands instead of being sold to a developer. The open space behind the school remains as a place where children can play.

Children enjoy playing on the school grounds of Parkview School

The open space is a great venue for games of soccer, baseball, and touch football. It’s also great place for running, dog walking, playing with a Frisbee, and riding a bicycle – and for tobogganing and snowboarding in the winter.

In the background is the hill that is located on the north side of the site. The Colonel Samuel Smith log cabin was located in an area to the front of the baseball backstop. Jaan Pill photo

There’s a hill on the north side, which is a great feature if you like to roll down a hill from time to time, as many children like to do. Sometimes you’ll see three or four children rolling down the hill at the same time. These kinds of games always give rise to a great deal of laughter, conversation, and enjoyment.

When you’re walking across this space, which is surrounded by buildings and trees, you realize how extensive it is. People can be seen walking across the school grounds in all seasons of the year.

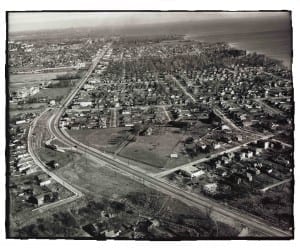

Aerial view looking east along Lake Shore Blvd West from near Long Branch Loop, Ontario Archives Acc 16215, ES1-814, Northway Gestalt Collection.

This is what the open space looked like in November 1949. In this aerial photograph from the Ontario Archives, you can see the main building of the Colonel Smith homestead as well as the outbuildings, including some located at what is now the end of Villa Road. We owe thanks to Michael Harrison for sharing this photograph with us.

Toronto board announces sale of Parkview School

Last year, on October 26, 2010, I learned something about Parkview School that stopped me in my tracks. On that day, I was reading the minutes of a recent school board meeting, posted at the website of the Toronto District School Board. I learned, from the minutes, that on June 23, 2010, the Toronto public school board had announced that Parkview School was surplus to its needs, and was going to be sold.

I began to speak with friends and neighbours about the pending sale of the school. If another school board or college bought this site, everything would work out fine. The alternative would be purchase of the school by a developer.

Two of the key people in our discussions, starting in October 2010, were Bert Crandall and Michael Harrison of Toronto. They shared with us a great deal of archival research regarding Colonel Samuel Smith and his homestead. Bert Crandall established our first contacts with Dena Doroszenko, the archaeologist who did a preliminary archaeological survey at the school in 1984, at the invitation of the Long Branch Historical Society. Michael Harrison, meanwhile, has ensured that the Smith homestead is registered in the province’s archaeological sites database and in a City of Toronto database.

Starting in October 2010, we contacted public officials to get information about the sale of the school. We met with Toronto District School Board Trustee Pamela Gough, who represents Ward 3, Etobicoke-Lakeshore, as well as Shirley Hoy, chief executive officer of the Toronto Lands Corporation, and Donna Jondreau, manager of real estate for the Toronto Lands Corporation.

The Corporation manages the sale of surplus schools on behalf of the Toronto public school board. There is a clearly defined process whereby the Toronto Lands Corporation must offer a property such as Parkview to a specified list of school boards, colleges, and levels of government, in order of priority.

If no offer is received from any of these public bodies within 90 days, the Toronto Lands Corporation is authorized to list the property on the open market, at fair market value. At that time any interested purchaser, such as a developer, can submit an offer.

Some time later, Trustee Pamela Gough announced that the French public school board, Conseil scolaire Viamonde, had made an offer to buy Parkview School. This was good news for the community.

At a meeting on January 24, 2011 at Lakeshore Collegiate Institute, officials of the Toronto public board, the Toronto Lands Corporation, and Conseil Viamonde shared information about the pending sale of the school. Residents attending the meeting expressed strong support for the sale.

Not long after, however, we learned there was a slight complication. The French public school board didn’t actually have the money, at that point, to buy the school. In order to buy the school, Conseil Viamonde would first need to get funding from the Ontario Ministry of Education.

We came to realize, at that point, that it might be a good idea for us to organize a letter writing campaign. We decided to write letters to Laurel Broten, the local MPP, to encourage her to expedite the release of provincial funds to enable the sale of the school to proceed.

We owe thanks to a large number of people who joined us in this letter writing campaign. Members of the Long Branch Historical Society wrote letters, as did owners on the south side of the condominium building at 3845 Lake Shore Blvd. West, just north of the open space. The condo owners on the upper floors have a great view of Lake Ontario. Some people wrote letters from as far away as Yellowknife, in the Northwest Territories.

It may be noted that after the Smith homestead buildings were torn up in 1955, a gas station and garage were built where the condo building now stands. A food store and parking lot were built around that time where the townhouses, north of the open space, now stand. These photographs from around that time are from the aerial photograph of Long Branch that is currently on display at the Long Branch Public Library.

Under the school grounds are located the remains of Colonel Samuel’s homestead

In our letters to Laurel Broten, we shared as much information about Colonel Samuel Smith as we could easily fit onto one page of text.

We said that the residents in Long Branch strongly supported the purchase, by the French public school board, of the Parkview School property.

We mentioned that a preliminary archaeological survey had been conducted in 1984, and we said that we looked forward to a complete survey of the site in the future.

We mentioned as well that the open space where the archaeological remains are located provides a year-round venue for children to play. We noted that residents of all ages walk across the grounds every day in all seasons of the year.

We remarked, in our letters, that the open area provides green space for children from neighbouring buildings at 25 Villa Road and the townhouses along Lake Shore Blvd. West, which have limited open space in their complexes. Many of the children in these buildings are first generation immigrants. The open space allows them to make friends and connect to the community.

We also mentioned that Colonel Samuel Smith, who lived from 1760 to 1826, was a Loyalist officer with the Queen’s Rangers in the American Revolutionary War. Samuel Smith was granted a large tract of land in Etobicoke in 1793. The colonel’s log cabin, along with other buildings built on the site over the years, was located on what are now the school grounds of Parkview School.

We added the following information:

Originally a log cabin to which extensions and siding were added, the Smith family house was in continuous use for about 152 years from 1797 until around 1949. It was torn down in 1955, to make room for a playground. Parkview School was opened in 1959 to alleviate overcrowding at James S. Bell School on Thirty First Street.

[It may have been in use a few years after 1949; according to a Feb. 19, 1955 Toronto Star article, the Christopherson family lived at the house until about 1952. If that information is correct, then the house would have been in continuous use for about 155 years. That said, the newspaper accounts from those years occasionally include errors, for which reason I am not keen so say anything definitive about such matters unless it’s been corroborated through several reliable sources. By way of an illustration, of unfounded statements, the above-mentioned Feb. 19, 1955 Toronto Star article notes that the Smith log cabin is “believed to be the oldest in Ontario.” The article does not say what the source of the statement is; given the lack of citation or evidence, the claim that is made is dubious. The Feb. 19, 1955 article also notes that the house was to be torn down to make room for an extension to a supermarket parking lot. Other reports from the era assert (see previous paragraph above) that the house was torn down to make room for the Parkview School playground.]

Samuel Smith, we noted, served for two terms as Administrator of the Executive Council of Upper Canada, a position equivalent to Lieutenant-Governor. His portrait hangs in the Legislative Building at Queen’s Park. In December 2010, area residents including children celebrated the Colonel’s 250th Birthday, on the assumption that he was born in 1760. Colonel Samuel Smith Park is named after the colonel, as is the Colonel Samuel Smith Ice Trail.

We mentioned, in our letters, that we seek to ensure that the open space where the colonel’s house once stood remains in public hands – and remains an open space. By way of conclusion, we said that any help that Etobicoke-Lakeshore MPP Laurel Broten could provide, by way of expediting the release of funds for the purchase of the school, would be very much appreciated by area residents.

It may be noted that sometimes the year of birth for Samuel Smith is given as 1756. In her archaeological report of 1984, however, Dena Doroszenko offers evidence suggesting that 1760 is the more likely year of birth.

Funding for Scolaire Viamonde is initially refused

In March 2011, as our letter writing campaign was well under way, we got some news that was not very promising.

We learned that the Ontario Ministry of Education had decided they would not be releasing funds for the purchase of Parkview School by the French public school board. At that point it appeared that our letter writing campaign had gone nowhere.

In the spring of 2011, starting around April, I was occupied with a video project in my work as a documentary filmmaker and writer. During that time, I received some additional news regarding Parkview School.

The most recent news was that negotiations were in fact still ongoing between the Ministry of Education and Conseil scolaire Viamonde, after all.

As well, we learned that the Toronto French Catholic District School Board had now also expressed interest in the purchase of the school, given that the province had initially refused to provide funding for Conseil Viamonde to complete the sale.

This meant the Ministry of Education was now negotiating with not one but two French language school boards with regard to the school.

We also got news that the negotiations had stalled. They were, in the spring of 2011, not going anywhere.

Around this time we also received some additional advice – namely, that we should organize another round of letters. We learned at that time that a second round of letters might cause the negotiations, which had been stalled, to start moving forward again.

My own thought at that point was that another round of letters would be a lot of work. But once the video project I was working on was completed, I began to organize another round of letters to Laurel Broten, the MPP for Etobicoke-Lakeshore.

By that time I realized that a second round of letter would be a great way to show that the community was capable of a sustained effort. Many people once again wrote letters.

Late in August 2011, we got some good news.

We learned that MPP Laurel Broten would soon be making an announcement concerning Parkview School. We did not know the details of the announcement, but we had the impression that the community would be pleased.

The official announcement, which was attended by a good number of enthusiastic area residents, was made at 11:00 am on August 25, 2011 at the front of Parkview School on Forty First Street.

Laurel Broten makes official announcement on August 25, 2011

This photograph, by Deborah Baic of The Globe and Mail, shows Etobicoke-Lakeshore MPP Laurel Broten in conversation with area residents just after she had announced that the province would provide $5.2-million in funding for the purchase of Parkview School by the French public school board Conseil scolaire Viamonde.

This photograph, from an August 26, 2011 article by Carys Mills, is the property of The Globe and Mail, and is displayed with permission. An article by Cynthia Reason, in the September 1, 2011 edition of the Etobicoke Guardian, also described the purchase of the school by Conseil Viamonde.

We owe thanks to many public officials – including MPP Laurel Broten and Trustee Pamela Gough – and many residents from Long Branch and elsewhere for the work that we have done together to ensure that Parkview School remains in public hands.

Dena Doroszenko conducted a preliminary archaeological dig in 1984

I want to speak in more detail about the archaeological features of the Smith homestead. The house where Samuel Smith and his family lived was subjected to a very thorough bulldozing in 1955. Dena Doroszenko has provided valuable details about the razing – that is, razing as in r-a-z-i-n-g – of the Smith house.

We owe thanks to the Long Branch Historical Society for inviting Doroszenko to conduct the preliminary archaeological dig in 1984. As well, the Etobicoke Board of Education (which later became part of the Toronto District School Board), the City of Etobicoke (which later became part of the City of Toronto), the Etobicoke Historical Society, and the Province of Ontario were also involved with the survey. The resulting report was a key ingredient in our recent letter writing campaign.

1984 was the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the official founding of the City of Toronto. Doroszenko had just finished her master’s degree and was going into the Ph.D. program in archaeology at the University of Toronto. She had been working off and on as a consultant with the City of Toronto, on one of their properties, when the Long Branch Historical Society contacted her. They were looking for someone to do a small dig at the Parkview School site, in connection with Toronto’s anniversary. She took on the project, and the dig was completed in the summer of 1984.

A small amount of money was available, which was enough, because Doroszenko was able to get a couple of volunteers. Members of the Long Branch Historical Society came out to help. She also had an undergraduate student with her for twelve days. Another graduate student did the mapping for the project. In the fall, still another undergraduate student did a geophysical survey of the site.

The archaeology project found a large amount of artifacts elsewhere on the site, but not much came out of the flat part of the schoolyard where the original Samuel Smith house had stood. That would indicate that something has happened in the area. Given that historic maps show where the house was located, we would expect to still have artifacts showing up, but almost none were found in that area in 1984.

Doroszenko is certain that the 1984 dig was looking for the Smith house in the right area of the schoolyard. The project looked at two registered surveys. These surveys showed some slight differences in the orientation of the house. The 1984 project looked at both surveys and ensured that both possible orientations were taken into account when the digging began.

Doroszenko believes that when the Smith house was demolished, it was bulldozed into the embankment where the townhouses are now standing. Everything was shoved up on the north side to create an embankment, a rise in the land, which is what you see now if you walk in the area.

A study of the soil gave no indication that there had in fact ever been a building where maps show that the Samuel Smith cabin had been built in 1797. The flat area of the open space had been completely razed – as in r-a-z-e-d – in terms of a complete scraping of the soil by earth moving equipment. The area has been graded, which means that everything had been shifted.

Stone foundations were found, in 1984, in the embankment area near where the townhouses now stand. These were likely the foundations of the outbuildings that historic maps have indicated were close to the original building. There had been an earlier outbuilding, which was torn down at some point. Thereafter, another outbuilding had been built on top of the original foundations. Two stone foundations are located, one on top of the other, close to the fence on the embankment. These were immediately north-east of the 1797 house. In between the gap, separating the two foundation walls, a very large amount of artifacts were found in 1984.

Also in 1984, the survey investigated the south-west corner, and the western wall, of one of these outbuildings. There was time, during the survey, to look at barely a quarter of the building. The rest of the building would appear to be still intact in the ground.

The 1984 survey did not dig in the interior of the outbuilding that was uncovered. That’s because the presence of collapsed rubble inside the structure meant it was not safe to dig in the interior. But it was possible to trace the outline of a portion of the building.

A very small number of artifacts were found in the area of the Smith house. There is a possibility of finding more artifacts in a future survey of the area where the house stood. The 1984 report recommended more archaeological testing in this area.

The 1984 report recommended a full archaeological survey

There has been discussion about organizing a full archaeological survey in the future. Whether or not one ever takes place depends on a lot of things, including what the new owners want to do. Speaking with the new owners will be among our first steps with regard to a possible complete survey.

An area of particular interest for a full archaeological survey is the embankment – the small hill close to where the townhouses are located. This area warrants further testing, given that two outbuildings, right on top of each other, are located on the hillside. It would be of much interest to excavate the entire outbuilding in that area.

Because we know where the walls of the foundations for the outbuildings are located, it would be possible to create a commemorative garden on the embankment. A garden, dedicated to Colonel Samuel Smith, could be built along the footprint of the foundations.

Domestic spaces have undergone many changes over the years

The Colonel Smith site, as Dena Doroszenko has explained, was one of the earliest farmsteads in this part of the city. Anything that tells us a little bit more about what it was like to live in this area of the city, in the late 1700s and early 1800s, is of interest to archaeologists.

Starting in 1797, living at the Smith homestead was very much a matter of living in the country, in a clearing in a forest. Over time the remaining forests in the area were cleared. Then over time we see the encroachment of the growing city. The farmstead in the countryside is transformed, with the passage of time, into an urban farmstead. Over time, we see the property boundaries changing. We see the types of buildings that are needed also changing. We see additions, substitutions, and demolitions under way, in response to urbanization and new technologies.

Doroszenko has studied many sites like the Smith homestead. She speaks of this work as the archaeology of domestic space. The Ashbridge Estate, east of the Don River, by way of example, shows similarities to the Colonel Samuel Smith homestead. The two homesteads are, in a sense, mirror images of each other. The Ashbridge Estate had its beginnings around 1795, starting with a land grant and the building of a log cabin. We see, in both ends of the city, a succession of generations living on the same land, in a succession of houses. Another archaeological site that is similar to these is the Spadina House in Toronto.

There’s been discussion about a historic plaque

Over the past year there has also been discussion about a plaque for the Colonel Samuel Smith homestead site. The organizing of a plaque is usually done in collaboration with the property owner, which in this case is Conseil scolaire Viamonde. As well, the Ontario Heritage Trust also has a program of Conservation Easements, which are always negotiated with the property owner. A Conservation Easement would limit what can be done with the open space, and would remain on title even if the ownership changes in the future.

The Samuel Smith site currently is registered in the province’s archaeological sites database and in a City of Toronto database. That gives it a slight measure of protection. If the site were also designated as a historic site, that would offer additional protection. The greatest amount of protection would be through a Conservation Easement.

We have many potential projects to think about. The first step will involve the opening of a dialogue between the local community and Conseil scolaire Viamonde.

By way of summary, we owe many thanks to many public officials and area residents for what has turned out to be a good news story regarding the homestead of Colonel Samuel Smith.

There are many possible next steps in the work we are doing together, as a community, with regard to the Colonel Smith homestead site.

I want to close by expressing thanks to Barry Kemp for inviting me to speak with you this evening about Colonel Samuel Smith. I look forward to working with Barry Kemp and many other people who are enthusiastic about local history, in my role, starting in January 2012, as the new president of the Long Branch Historical Society.

[By way of an update: The election for a new president for the society on January 17, 2012 ended in a tie. Jaan Pill was elected president on March 20, 2012. He resigned on June 19, 2012.]

Updates

A March 22, 2014 paper is entitled “On Conservation’s Edge: A Call for a Social Science of Destruction.”

A March 28, 2015 paper is entitled “Heritage Hoarders? Archaeological Cultural Heritage Resources in Ontario.”