The first engineered alteration of Etobicoke Creek began in 1929 to allow for the westward extension of Lake Promenade

Oblique view of Marie Curtis Park including mouth of Etobicoke Creek, May 2010. © Toronto and Region Conservation Authority

The Physiography of Southern Ontario (1984) by Lyman John Chapman and Donald F. Putnam is a classic geological study expressed in clear and authoritative language.

A voice of authority does not in itself establish that a writer’s rhetoric is congruent with reality, but it’s often a pleasure to read a writer who speaks with authority.

In this case, the authors also demonstrate that their work is based on solid research, the outcome of many summers of field studies, further adding to the pleasure of reading this classic text.

When I think about flood plains I often think of how Chapman and Putnam underline the reality that a floodplain is not suitable for housing. Sooner or later flooding will occur in such a setting.

Floodplains belong to the streams that run through them

You build a house on a floodplain and the day will come sooner or later – it could be an event that occurs once in a hundred years, but it will arrive – when the house and its inhabitants may be swept away by a stream of water.

Such perils notwithstanding, houses were built upon the floodplain at the mouth of Etobicoke Creek, for many reasons.

Mid-1920s, near mouth of Etobicoke Creek. Connie, Cyril, George and Rene Durance, Florence Morrel. Photo credit: Doris Durance. © Durance family and Robert Lansdale

Such buildings offered an opportunity to spend pleasant and enjoyable summers in cottage country, as many former residents have remarked.

Some people I’ve been in touch with in recent years have said that playing at the mouth of the creek as children were among the happiest times of their lives.

One of the features of the former cottage lots at the mouth of Etobicoke Creek – as Doreen Durance of Long Branch, who spent many summers by the lake decades ago, has mentioned to me – is that the houses were wide apart. There was usually plenty of room between them, she reports.

Aside from the fact it was on a flood plain, it was a very pleasant setting for a cottage community.

In some cases, the lower cost of housing built on a flood plain may have been a variable in determining where to build a house. This aspect of home ownership is in turn related to the historical development of western concepts of property, as John C. Weaver (2003) among others has explained. Generally speaking, the house on the hill will cost a little more than the house built on the flood plain.

A Glimpse of Toronto’s History (2001)

With regard to Long Branch, three historical overviews that I’ve found of particular value include:

A Glimpse of Toronto’s History: Opportunities for the Commemoration of Lost Historic Sites (2001), a report prepared with key input from Wayne Reeves;

Regional Heritage Features on the Metropolitan Toronto Waterfront: A report by Wayne Reeves to the Metropolitan Toronto Planning Department (1992); and

Toward the Ecological Restoration of South Etobicoke (1997). The lead author is Michael Harrison. You can download the report here.

What I take to be minor factual errors occur in the first two above-mentioned studies, such as the assertion that Colonel Samuel Smith was granted a large tract of land in Long Branch in 1799, whereas many sources note that Smith was granted the tract in 1793.

Similarly, in the 2001 text – A Glimpse of Toronto’s History – a map of the flood plain at the mouth of Etobicoke Creek positions a building labelled “Col. Smith’s House” at a location, on the colonel’s homestead, that does not match information available from other sources.

These are minor quibbles. The correct information is available from other sources.

Scenic beauty spot

Historically, the mouth of Etobicoke Creek was known as one of the finest wetlands and wildlife habitats along the Lake Ontario shoreline.

The 2001 text adds that the site has since become a textbook example of what not to do with a scenic waterfront location. In this case we have a scenic beauty spot that’s been polluted and engineered out of existence.

A feature of the area was the presence of once-enormous flocks of passenger pigeons, a species that was extinct by 1902.

The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places (2011)

The birds and animals at the Etobicoke Creek mouth would have been great to listen to. Palaeo-Indian nomadic hunters in Long Branch once would have heard the great animal orchestra which Bernard Krause (2011) – see link in previous sentence – has described.

A draft of the 2001 text, A Glimpse of Toronto’s History (which is what I have at hand at the moment) notes:

“Surrounding the creek’s mouth and lower course were Carolinian forests of white pine and oak. At the mouth was an island, flanked on the west side by sandy flats and dunes, and a gradually growing peninsula.

“Annual spring floods enriched the lands around the mouth with nutrients. The marshes provided fish spawning grounds, and the creek was famous at one time for the salmon runs upriver. Aboriginal peoples grew corn on the fertile flatlands at the mouth, and later introduced squash and beans.”

“The Mississauga Indians [that is, Mississauga of the New Credit First Nation], from whom the land had been taken,” the text adds, “were guaranteed perpetual fishing rights in the river, but were driven out by commercial fishermen and advancing settlement.”

Colonel Samuel Smith left most of Etobicoke Creek as he found it and built (in 1797) only his homestead – torn down in 1955 – at a location not far from the mouth of the stream.

Serious flooding began about 1850

“But he allowed timbering of his lands, as did others,” according to the 2001 overview, “and by 1842 half of the great forests of Etobicoke Township had been cut down. As a result, serious flooding problems began about 1850.”

In 1871, as the 2001 text notes, Colonel Smith’s son sold 500 acres of the Smith property to James Eastwood, “and within a few years the forest cover was gone and the creek flats were covered with shacks and shanties.”

You can access a PDF file from a Toronto and Region Conservation Authority website that shows an April 7, 1923 photo of a typical shack from later decades on the Etobicoke Creek flood plain.

I would add in passing that the schematic diagrams, overlaid on photos, on the first page of the above-noted TRCA document, purporting to indicate where Etobicoke Creek used to run in a previous era, are somewhat absent of precision.

By way of example, Island Road used to run down the centre of the island formed by the two branches (of which only the eastern version now remains, in channelized form) of Etobicoke Creek south of Lake Shore Blvd. West.

The road remains in place [albeit it does not follow exactly the same route as before], with the same name as before. It was never submerged under the western channel of the creek, as the diagram on the first page of the above-mentioned PDF file erroneously suggests.

This is a minor point; on the whole the PDF file that I refer to is highly valuable.

Development was accompanied by pollution and destruction of wildlife habitat

The 2001 document referred to earlier notes that Etobicoke Creek is a large system with many tributaries, draining an area of 205 square kilometres. About one-quarter of the creek’s system is within the City of Toronto boundaries.

The mouth of the creek did not have good anchorage, the 2001 text notes, but some shipping was done from there, and Colonel Smith built the ship Defiance there using timber from his own oak forest in about 1825.

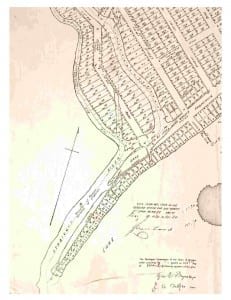

1920 map showing Long Branch subdivision near mouth of Etobicoke Creek. Part of the subdivision is located along the western extension of Lake Promenade west of Forty Second Street.

The Long Branch lands south of the Lake Shore Road were subdivided by the James Eastwood family in 1920 and developed as residential subdivisions.

Between the two World Wars, lands in Long Branch and surrounding communities unsuitable in their natural state for development were filled in and creeks and streams buried, with few remaining by 1900.

“Groundwaters became polluted,” the 2001 text notes. “Waters flowing into the system from Brampton and Mississauga were contaminated, the worst being from Spring Creek, which ran through the airport lands. Etobicoke Creek became the most contaminated system in the region, with higher concentrations of PCBs than elsewhere. Fish and wildlife were either reduced or vanished.

“Reports and studies over the years consistently recommended remediation and removal of the weir installed on the creek by the Toronto Golf Club, because it blocked fish movement.”

Work in 1929 set the stage for future flooding; the eastern branch of creek was channelized starting in 1949

The 2001 document notes that first engineered alteration of the lower creek began in 1929, when the beach sandbar across the mouth of the river was reinforced by cribwork to allow for the extension of the Lake Promenade toward the Mississauga border near where Applewood Creek is located.

An online definition speaks of cribwork as “a supporting framework of beams, logs, etc. built in layers, each layer having its unit at right angles to those of the layer below.”

Severe flooding occurred in 1948 because of this additional block to the outlet.

“In 1952, more flooding destroyed the houses on the sand flats and sandbar. In response, Long Branch Council acquired 27 lakefront lots and began to plan for flood control. It had become inescapable that the channelling done in 1949, taking the creek through the sandbar, was woefully inadequate.”

Before the planning was complete, in 1954 Hurricane Hazel arrived.

“By this date, the Metropolitan government had been formed and plans were laid for improvements beginning with the expropriation of 183 floodplain properties. The area was to be raised by landfill, the flats converted to parkland, and the lower creek re-channelled.

“Both the degree of alterations and costs were enormous. In 1959, Marie Curtis Park was opened. By this date, there was not a single trace of the original creek mouth remaining, although some remnants of the surrounding forest may still be seen upstream on the adjoining lands.”

Textbook illustration of damage of human interference

The draft of the 2001 document – the final version is identical or similar – concludes:

“Etobicoke Creek and its mouth are unquestionably important, and the history of change introduced there is a textbook illustration of the damage that can be done by human interference.

“Not only is the creek a boundary between two townships and now two cities, it has been a major wildlife habitat and scenic beauty location that has been almost polluted and engineered out of existence and should be used as a guide on what not to do to a watercourse.”

Jane’s Walk

We’ve compiled this information as part of preparations for the Jane’s Walk in Long Branch on May 4 and May 5, 2013.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!