John Boyd committed his infantry before his artillery could properly support them: Battle of Crysler’s Farm, Nov. 11, 1813

In a previous post, I have described the Battle of Crysler’s Farm on Nov. 11, 1813 during the War of 1812. The British side numbered about 800, the American side about 4,000 – or maybe as much as 7,000 as mentioned in a reference which follows below.

Vastly outnumbered but better trained, the British side prevailed.

As a consequence of this battle and the Battle of Chateauguay on Oct. 26, 1813, the American side gave up on its plan to conquer Canada.

Field of Glory (1999)

In his study entitled Field of Glory: The Battle of Crysler’s Farm, 1813 (1999), Donald E. Graves provides the following assessment of a key feature of the Battle of Crysler’s Farm:

Responsibility for the defeat must be charged to [John] Boyd, [Morgan] Lewis and, most of all, James Wilkinson. Despite his lengthy military career, Wilkinson had never commanded even a regiment in combat, let alone an army of more than 7,000 men, and his actions and those of Morgan Lewis on 11 November 1813 were irresponsible. Wilkinson’s one positive step that day had been to order [Timothy] Upham to reinforce Boyd, but this order had been anticipated and issued by [Joseph] Swift. Other than that, neither general had done a single thing to assist their subordinates, yet although they refused to exercise command, they refused to give it up, and the result was disastrous. It therefore fell on John Boyd, an officer clearly promoted well beyond his level, to fight the battle – and a very bad job he made of it.

Boyd committed his infantry before his artillery could properly support them and did not use his superior strength to advantage but instead wasted the lives of his troops in separate and uncoordinated attacks which were defeated in detail by a well positioned opponent. Both he and his brigade commanders encountered problems deploying and manoeuvring their formations, problems resulting from their own inexperience and the poor and confused state of training in their commands. It was also Boyd’s responsibility to ensure that his troops were supplied with ammunition before and during the action, and in this he was totally remiss. For most of the engagement, John Boyd seems to have wandered aimlessly about wondering what to do next, and without the efforts of Swift and [John] Walbach the day might have been worse than it was, because, in effect, no American officer was in overall command during the battle.

1812: A Guide to the War and Its Legacy (2013)

The Battle of Crysler’s Farm is best understood in the context of the War of 1812 as a whole. An excellent overview of the context is provided by 1812: A Guide to the War of 1812 and Its Legacy (2013). It’s an impressive and readable study, with great illustrations, photographs, and maps. Among the contributors is Terry Copp, whose work I follow with interest.

A blurb for the book at the Toronto Public Library website notes:

The authors of 1812: A Guide to the War and Its Legacy believe that the War of 1812 was an important event in North American history with lasting consequences for Canadians, Americans, and First Nations. This guidebook, published by the Laurier Centre for Military Strategic and Disarmament Studies, uses modern satellite images, archival records, paintings, and contemporary photographs to help readers understand what happened during the war and why it happened that way.

In the edition of the book that’s available from the Toronto library, the title is spelled as “1812: A Guide to the War and its Legacy.” I see no rationale why “its” should not be capitalized. The above-noted blurb correctly capitalizes the word. The idiosyncratic approach to the spelling of the title detracts, in a small way, from the quality of the book, in my view. I speak as a retired elementary teacher. Such small but in my view significant details invariably command my attention.

Archaeological and Historic Sites Board of Ontario

A text, provided by the Archaeological and Historic Sites Board of Ontario, on a plaque at the site offers the following overview of the Battle of Crysler’s Farm:

In November 1813, an American Army of some 8000 men, commanded by Major-General James Wilkinson, moved down the St. Lawrence en route to Montreal. Wilkinson was followed and harassed by a British corps of observation consisting of about 800 regulars, militia and [First Nations warriors] commanded by Lieut-Col Joseph Morrison. On November 11, Morrison’s force, established in a defensive position on John Crysler’s farm, was attacked by a contingent of the American army numbering about 4000 men commanded by Brigadier-General J.P. Boyd. The hard fought engagement ended with the Americans’ withdrawal from the battlefield. This reverse, combined with the defeat of another invading army at Chateauguay on October 26, saved Canada from conquest in 1813.

“Washington is burning”: September 2014 Harper’s Magazine

In a September 2014 Harper’s Magazine article entitled “Washington is burning: Two centuries of racial tribulation in the nation’s capital,” Andrew Cockburn notes:

To maintain a rosy view of the War of 1812, it is best to concentrate on the tattered banner and its mythic survival amid British rockets and bombs. There is less romance in the full story. It was a war of aggression, launched by President James Madison in hopes of conquering Britain’s Canadian colony, thought to be easy prey while the British were distracted by their life-and death struggle with Napoleon. Not for the last time, expert opinion expected a walkover. “The acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching,” wrote Thomas Jefferson soon after war was declared. A fellow ringleader of the war party, Henry Clay, assured Congress that “the militia of Kentucky are alone [able] to place Montreal and Upper Canada at your feet.”

A bond between two friendly peoples

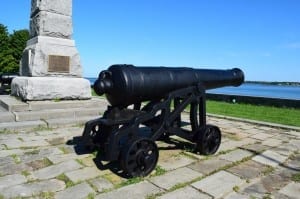

A plaque at the Crysler’s Farm site, erected in July 1963 by the Ontario-St. Lawrence Development Commission (see photo on left) reads:

In commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Crysler’s Farm, this plaque is dedicated to the Canadian and American nations whose common memories of old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago not only contribute to their separate heritages and traditions but form a bond between two friendly peoples.

Slavery

The previously-noted Harper’s article, which contrasts British and American attitudes toward slavery during the War of 1812, brings to mind Notes of a Native Son (1955, 2012) by James Baldwin.

I bought a print copy of the September 2014 issue of Harper’s Magazine. Among the features in the issue, which in my view delivers good value for money, is an article entitled: “Israel and Palestine: Where to go from here.”

The “Washington is burning” article refers, with regard to slavery, to The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1771-1832 (2013) by Alan Taylor, who has written several studies of North American history.

First Nations

The significant contributions of First Nations warriors to the outcome of the War of 1812 is a topic of valuable research by historians in recent years. We can add that, in that era as in others, the conventions of warfare were applied differentially.

I’m speaking in this context of warfare involving European settler societies as distinct from warfare involving First Nations societies.

As well, with regard to warfare as politics by other means, issues involving settlers societies, as distinct from First Nations societies, were addressed differentially.

I refer in this context to the settlement in 1814 of the War of 1812 and the political developments that shaped the North American continent in the years that followed. There is some consensus among historians, from what I can gather, that the losing side in the War of 1812 was the First Nations side.

Music

With regard to the War of 1812, we’re talking about what happened 200 years ago. How to access some of those years? How can we picture the times?

Music is among the best ways, in my experience, to gain entry, in one’s imagination, to previous, long-ago eras. I’m thinking not in particular of war songs, but of folk songs. Among the CDs in this category, from the Toronto Public Library, that I enjoy is: A Folksong Portrait of Canada / Un Portrait Folklorique (1994). The CD package includes information about each of the performers on the set of three CDs and details about the origins of the songs.

Other sets of CDs of folk songs are also available from the Toronto library. Music offers a tremendous way for a person to get a sense of the history and ambience, especially as it relates to everyday life, of a any era.

Updates

A Sept. 24, 2014 New York Times article about Greek folk music is entitled: “Hunting for the Source of the World’s Most Beguiling Folk Music.” The link provides access to several music files, including “Epirotiko Mirologi,” an instrumental piece 4 minutes and 16 seconds in length, which is highlighted in the opening paragraph of the article.

With regard to Canadian folk songs, The Log Driver’s Waltz was a favourite among the songs that I used to play, from a audio cassette recording, during my years as a Grade 4 teacher.

An April 15, 2016 Globe and Mail article by Bob Rae is entitled: “Attawapiskat is not alone: Suicide crisis is national problem.”

An Aug. 10, 2016 CBC article is entitled: “Popular theory on how humans populated North America can’t be right, study shows.”

A Jan. 23, 2017 article at earlycanadianhistory.ca is entitled: “Anishinaabeg in the War of 1812: More than Tecumseh and his Indians.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!