Toronto and Montreal wiped out their farmsteads

I much enjoyed getting together for coffee on May 18, 2016 at the Birds and Beans Café in Mimico with Bob Carswell, who attended Malcolm Campbell High School (MCHS) in Montreal in the 1960s.

In those years I was also at MCHS; many years later, we both live in South Etobicoke in Toronto (in New Toronto and Long Branch respectively) near Lake Ontario.

The text below is based on a brief comment (see below) that Bob Carswell posted on Facebook regarding the history of Toronto cottage architecture.

Lost cottage architecture

I recently posted to Facebook a BlogTO Dec. 3, 2015 article by Derek Flack entitled: “Toronto’s lost cottage architecture hides in plain sight.”

Bob Carswell at Birds and Beans Cafe in Mimico in South Etobicoke close to Lake Ontario where he met with Peter Mearns and Jaan Pill in February 2015. Bob is listening to the MCHS school song on Jaan’s iPhone. Jaan Pill photo

The above-noted BlogTO article prompted me to think about small cottages that remain here and there in Long Branch.

Long Branch cottages

On May 20, 2016 I walked from the Gus Ryder Health Club to the Alderwood Library. I started walking west at Birmingham St. which at Twenty Second St. turns into Elder Ave. as you proceed west.

Along the way, on the side streets to the north of Elder, and at other points along the way, I saw many small cottages. I much enjoy seeing those small buildings.

I was reminded of a walk that I took with my late father, around the late 1960s or early 1970s in the area of Cartierville in the northern part of Montreal, during a visit home from Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. There were many small cottages that we visited. Each cottage evoked a sense of colour, warmth, and personality.

My father really enjoyed those cottages. That short walk was one of the highlights of my life, as I look back, from those years. We looked at the cottages, and talked about them. Here’s a post that I’ve written, some years ago, about that part of Montreal and the memories that remain for me, from those years:

View of school grounds, looking north toward Lake Shore Blvd. West, at former Parkview School. As I understand, the Colonel Samuel Smith homestead house, which was continuously occupied for over 150 years as a family home, was located just to the front (that is, to the south) of where a baseball backstop now stands, close to the horizon toward the right in the photo, near where the townhouses in the background are located. A closer view is available if you click on the photo, then click again. Jaan Pill photo

Farmers’ fields north of Montreal is where the City of Laval was built

Comment from Bob Carswell: Dec. 3, 2915 BlogTO article

When I posted the above-noted BlogTo article, featuring cottage architecture in Toronto, to Facebook, Bob Carswell commented:

View of Parkview School, photographed from top of Aquaview Condominiums, November 2012. Photo credit: Jaan Pill. Click on photo to enlarge it; click again to enlarge it further.

“Interesting…a great many homes can tell you where the original farms were as they were absorbed into local developments and disappeared from the skyline without moving an inch.”

His comment has prompted me to write the current post, which you are now reading.

Rural farmstead, transformed into an urban farmstead

Bob Carswell’s comment brought to mind the same theme – of the concept of original farms that were in time engulfed by a growing city – as it relates to Long Branch, the community where I have lived for the past twenty years.

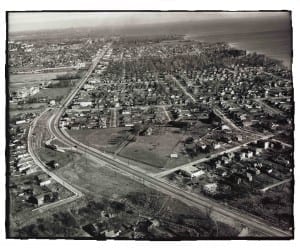

Aerial view looking east along Lake Shore Blvd West from near Long Branch Loop, Ontario Archives Acc 16215, ES1-814, Northway Gestalt Collection. Click on image to enlarge it; click again to enlarge it further.

That is indeed a fascinating phenomenon. It’s something that has struck me with regard to the Colonel Samuel Smith homestead at the grounds of the former Parkview School at 85 Forty First St. in south Etobicoke. I’ve discussed the transformation of the homestead at a long-read overview of the history of Long Branch, entitled:

A History of Long Branch (Toronto) – Draft 4

The relevant quote from the above-noted post reads:

Like the Ashbridge Estate east of the Don River, the colonel’s property began as a rural farmstead that was transformed into an urban farmstead surrounded by a growing city. The two farmsteads are mirror images of each other. As the archaeologist Dena Doroszenko has noted, one day the occupants of each farm were living in the countryside; and then the day arrived when the surrounding countryside had disappeared.

Nell and Robert Christopherson at the back of the Samuel Smith house, where they lived until 1952; the house was torn down in 1955. Photo © Betty Farenick and family

The colonel’s property began as a rural farmstead, which in time was transformed into an urban farmstead surrounded by a growing city. As the years passed, the occupants of the farm observed a dramatic change in their surroundings, without having travelled anywhere. What had been a farm out in the countryside became, with the passage of the years, a farm that was on its way toward being engulfed by a growing city.

[End of text]

Archaeology of domestic space

Dena Doroszenko, who conducted a preliminary archaeological dig at the Colonel Samuel Smith homestead site in 1984, speaks of an archaeology of domestic space.

The process of the transition from rural to urban spaces fascinates me. The city in history is metaphorically like a giant comic book amoeba that slowly grows in size and engulfs all of the farmsteads in its path. I have a longer overview of the topic at an earlier post, the speaking notes for a 2011 presentation that I made at a local library regarding the Samuel Smith homestead:

Colonel Samuel Smith and his homestead: Speaking notes for October 2011 presentation

Back view (facing south) of Colonel Samuel Smith homestead house, located at what are now the school grounds of Parkview School. Originally a log cabin, built in 1797, the house had siding and extensions added to it over the years. Photo © Betty Farenick and family

For most photos at this page, you can enlarge the image by clicking on it

The latter post speaks of the topic at hand in additional detail:

The Colonel Smith site, as Dena Doroszenko has explained, was one of the earliest farmsteads in this part of the city. Anything that tells us a little bit more about what it was like to live in this area of the city, in the late 1700s and early 1800s, is of interest to archaeologists.

Starting in 1797, living at the Smith homestead was very much a matter of living in the country, in a clearing in a forest. Over time the remaining forests in the area were cleared. Then over time we see the encroachment of the growing city. The farmstead in the countryside is transformed, with the passage of time, into an urban farmstead. Over time, we see the property boundaries changing. We see the types of buildings that are needed also changing. We see additions, substitutions, and demolitions under way, in response to urbanization and new technologies.

Doroszenko has studied many sites like the Smith homestead. She speaks of this work as the archaeology of domestic space. The Ashbridge Estate, east of the Don River, by way of example, shows similarities to the Colonel Samuel Smith homestead. The two homesteads are, in a sense, mirror images of each other. The Ashbridge Estate had its beginnings around 1795, starting with a land grant and the building of a log cabin. We see, in both ends of the city, a succession of generations living on the same land, in a succession of houses. Another archaeological site that is similar to these is the Spadina House in Toronto.

[End of text]

Some buildings, originally on a farm, have been preserved

The cabin the the colonel built in 1797 was demolished in 1955. However, some buildings in Long Branch and elsewhere remain, from earlier times.

By way of illustration, 28 Daisy Avenue, located north of Lake Shore Blvd. West between Twenty Sixth St. and Twenty Fourth St. in Long Branch, originally was located on a farm, before subdivisions began to occur:

Update regarding 28 Daisy Avenue: Notice of passing of bylaw

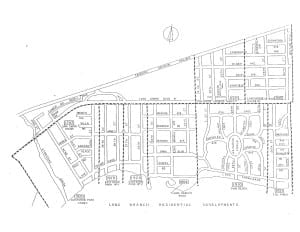

Long Branch Subdivisions Map. Daisy Ave. is located at the upper right-hand corner of the map; 28 Daisy Ave. is between Twenty Sixth Street and Twenty Fourth St. As with most other images at this overview, you can get a closer view by clicking on the image; click again to enlarge it further.

Canada’s Rural Majority (2016)

The topic of Toronto’s cottage architecture brings to mind a recent study by R.W. (Ruth Wells) Sandwell entitled: Canada’s Rural Majority: Household, Environment, and Economies, 1870-1940 (2016).

A blurb (I have broken the longer text into shorter paragraphs, for ease in online reading) for the book at the Toronto Public Library website reads:

Before the Second World War, Canada was a rural country. Unlike most industrializing countries, Canada’s rural population grew throughout the century after 1871–even if it declined as a proportion of the total population. Rural Canadians also differed in their lives from rural populations elsewhere.

In a country dominated by a harsh northern climate, a short growing season, long distances, and poor land, they typically relied on three ever-shifting pillars of support: the sale of cash crops, subsistence from the local environment, and wage work off the farm.

Canada’s Rural Majority is an engaging and accessible history of this distinctive experience, including not only Canada’s farmers, but also the hunters, gardeners, fishers, miners, loggers, and cannery workers who lived and worked in rural Canada.

Focusing on the household, the environment, and the community, Canada’s Rural Majority is a compelling classroom resource and an invaluable overview of this understudied aspect of Canadian history.

[End of text]

A back cover blurb for the book, which is published by the University of Toronto Press, reads:

Canada ‘s Rural Majority offers a concise introduction to the experience of Canada’s rural population in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Focusing on the household, the environment, and the community, R.W. Sandwell discusses the lives of Canada’s farmers, hunters , gardeners, fishers, miners, loggers, and cannery workers. This broad synthesis offers the following features:

- Coverage of five distinct regional environments : the Canadian Shield, the St. Lawrence Valley and Southern Great Lakes, the Prairies, the mountains, and the coasts

- Analysis of the connections between the local environment, global trends, and rural experience

- Discussion of aspects of rural life unique to Canada

Themes in Canadian History

Series Editor : Colin Coates

Books in this series are designed to open up a subject to the non-specialist reader. They pull together a large body of research and lay out the main themes and interpretations in a clear, accessible fashion.

[End of text]

Transition to urban industrialism

An excerpt (p. 80; I have broken the longer text into shorter paragraphs) from the book reads:

Many people experienced the rapid transition of society towards urban industrialism with considerable alarm; many regarded the growth of cities (crime, filth, and poverty seemed to define them in the late nineteenth century) as a negative trend, but one that more settlement on rural lands could correct.

In practice, at the same time that some rural people were viewing urbanization and industrialization with fear, others embraced the new technologies and the opportunities to travel and trade, and to purchase new goods.

Ruling elites in each province, however, had serious reservations about the social destabilization accompanying urbanization and industrialization, and used the rhetoric of a stable and knowable past to assuage their fears. Later generations would agree with British economist John Maynard Keynes that the solution to poverty in modern society lay in increasing the living wage and thus the spending power of the “masses,” leading to increased trade and manufacturing for the overall good of the urban-centred economy.

Historians such as E.A. Wrigley and Christopher Jones have recently argued that all of these transformations can ultimately be traced to the unprecedented wealth generated by the remarkable density and efficiency of the country’s new forms of energy: fossil fuels and electricity. Neither explanation was obvious to Canadians at the time; many were still convinced that “the solution” to Canadian urban problems lay in reaffirming the values and activities of an earlier rural society and encouraging more people to go “back to the land.”

[End of text]

Displacement of First Nations peoples

The processes by which European settler societies set up rural societies are highlighted in A History of Long Branch (Toronto) – Draft 4.

The history of Long Branch is part of the larger Canadian story, with regard to the growth of the settler societies, as noted by way of illustration at a previous post entitled:

Significance of the late 1880s for New Toronto and the First Nations of western Canada

Also of relevance: Final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Volume One: Summary: Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future (2015).

Ancient bison fossils offer hints about 1st humans in southern Canada – June 6, 2016 CBC report

Among the displacements, of First Nations inhabitants, that have occurred in Long Branch is the one that occurred, following the arrival of the European settler society, at the mouth of Etobicoke Creek. The original treaty permitted ongoing fishing by First Nations peoples; such fishing rights were pushed aside once commercial fishing was instituted along the Lake Ontario shoreline.

Similarly, West Mineola along the Credit River in Mississauga was originally First Nations territory, as historical and archaeological evidence indicates; again, following the arrival of the European settler society, the original inhabitants were displaced.

A feature of West Mineola is that the neighbourhood has been designated as a cultural heritage landscape; development that occurs is required to take into account the historical character of the buildings and landscape. Unlike southern Etobicoke, the streams that were originally in place have (in many cases, as I understand; I will need to read further about this topic) remained in place; as a consequence, their presence adds immeasurably to the real estate value of the area. In southern Etobicoke, the streams that used to be in place were by and large eliminated by the early 1900s.

The geographical imagination

The manner in which space is used – space in a geographical sense; space as conceptualized as land – can be analyzed from a wide range of perspectives.

Military history and the geographical imagination comes to mind. The concept is from a study by James A. Tyner:

Genocide and the Geographical Imagination: Life and Death in Germany, China, and Cambodia (2011)

Some previous posts that address the topic include:

What conceptual framework drove the British to establish themselves in Long Branch?

In standard usage, gentrification is a limited concept; the underlying process is of a wider import

Extremely violent societies

The concept of extremely violent societies I have explored at a previous post:

Christian Gerlach’s 2010 genocide-related study focuses on extremely violent societies

Gated communities and ghettos

Gated communities and ghettos also come to mind.

Click here to access previous posts about gated communities >

A June 2016 Atlantic article is entitled: “The Destructive Legacy of Housing Segregation.” The subhead reads: “Less visible than the rise of income inequality in America is its impact in shaping the country’s urban neighborhoods. Two books – by Matthew Desmond and Mitchell Duneier – could help change that.”

The article brings to mind previous posts:

Of related interest is Ken Greenberg’s characterization (if I remember this correctly) of modernist architectural practices as like a time bomb with a long fuse:

Ken Greenberg (2011) talks about early urban planning in Chicago

To be more precise, regarding the time-bomb reference, the above-noted post notes that:

Greenberg notes that in the aftermath of the European Industrial Revolution, which gave rise to deplorable living conditions in industrial cities, a “modern movement” in architecture emerged.

He characterizes the movement (p. 22) as “an intellectual time bomb with a very long fuse” fueled by good intentions.

[End of text]

Ambiguity and sense-making

A May 16, 2016 Science of Us article is entitled: “Here’s a New Way to Make Sense of Good People Doing Bad Things.” I mention the article in passing, as I find it useful in organizing my thoughts about the topics at hand. The article refers to related articles including an Oct. 19, 2015 Science of Us article entitled:

The Bad Things That Happen When People Can’t Deal With Ambiguous Situations

Frames (as in mind-sets and world views)

Economic and political structures and frames drive the use of geographical space; an overview of economics and related topics is presented by Darryl Cunningham in:

The Age of Selfishness : Ayn Rand, Morality, and the Financial Crisis (2015)

Dark Age Ahead (2004)

The above-noted graphic overview by Darryl Cunningham serves as an update to Dark Age Ahead (2004) by Jane Jacobs. A blurb (which I have broken into shorter paragraphs) at the Toronto Public Library notes for the latter study notes:

Visionary thinker Jane Jacobs uses her authoritative work on urban life and economies to show us how we can protect and strengthen our culture and communities. In Dark Age Ahead, Jane Jacobs identifies five pillars of our culture that we depend on but which are in serious decline: community and family; higher education; the effective practice of science; taxation and government; and self-policing by learned professions.

The decay of these pillars, Jacobs contends, is behind such ills as environmental crisis, racism and the growing gulf between rich and poor; their continued degradation could lead us into a new Dark Age, a period of cultural collapse in which all that keeps a society alive and vibrant is forgotten.

But this is a hopeful book as well as a warning. Jacobs draws on her vast frame of reference – from fifteenth-century Chinese shipbuilding to zoning regulations in Brampton, Ontario – and in highly readable, invigorating prose offers proposals that could arrest the cycles of decay and turn them into beneficent ones.

Wise, worldly, full of real-life examples and accessible concepts, this book is an essential read for perilous times.

From the Hardcover edition.

[End of text]

Greenbelt expansion

On a positive note, proposals have been made to expand the greenbelt in Ontario, rather than permitting the giant comic book amoeba, as I have described it, to continue its expansion:

The Greenbelt is smart, sustainable living: Lou Rinaldi, MPP for Northumberland-Quinte West

Also of interest and equally on a positive note, a May 19, 2016 Urban Strategies article is entitled: “Ontario’s First Steps to Inclusionary Zoning.” The proposed legislation addresses themes that are touched upon in a previously-noted June 2016 Atlantic article entitled: “The Destructive Legacy of Housing Segregation.”

A June 2016 Atlantic article is entitled: “China’s Twilight Years: The country’s population is aging and shrinking. That means big consequences for its economy – and America’s global standing.”

A June 15, 2016 Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy article is entitled: “China issues demolition order on world’s largest religious town in Tibet.”

The Boundary Bargain: Growth, Development, and the Future of City County Separation (2016)

A blurb at the Toronto Public Library website for The Boundary Bargain: Growth, Development, and the Future of City County Separation (2016) [I’ve broken the text into shorter paragraphs] reads:

The Boundary Bargain: Growth, Development, and the Future of City-County Separation addresses a burgeoning area of study in Canadian local government-growth, development, and sprawl.

Specifically, the manuscript examines the role of municipal organization in urban growth and the role of institutions in the city-county separation. Using Ontario as case study, the manuscript highlights the coordination problem posed by this separation.

Traditionally, the two areas have been seen as distinct with different sets of values, economies, labour trends, and ways of life. Despite these cultural and geographic divergences, rural and urban have always had a reciprocal relationship and both play an important role in the strength of the national economy, trade, commerce, and population growth. This complex inter-connected relationship presents a challenge to policy-makers. In Ontario, more recent structural responses to the divide have tended to view the city and its rural periphery as part of a common political unit,if not also a sociological and economic one.

In the past when an urban area of a county was declared a city it was politically separated from its surrounding county thereby severing any institutional linkages the two once shared. More recently responses to regional growth began to see urban and rural as connected and have since designed institutions that linked the two in order to provide greater policy and service continuity.

The Boundary Bargain details this shift in institutional thinking and municipal organization while examining best practices for addressing growth and development from a regional perspective.

[End of text]

Updates

A Nov. 12, 2016 Globe and Mail article by Doug Saunders, entitled “Whitewashed,” features an American interview subject who lives in a gated community: “Although her neighbourhood, which is gated and predominantly white, does not see much crime, her family had armed up, accumulating more firearms to protect itself.” I’ve removed the link for the article as the link is no longer active.

A Jan. 23, 2015 BuzBuzzNews article is entitled: “Art Deco or Edwardian: A pictorial guide to early 20th century Toronto housing styles.”

Graeme Decarie comments:

Yes, I lived for a time in a mid-nineteenth century Decarie farmhouse in Pointe Claire. There are still some in St. Laurent. (There’s also a Decarie from St. Laurent who’s up for sainthood.)

There’s the very old, pink brick farmhouse in Westmount (can’t remember the name of the street – Vendome?). And across the street from it is a monster, late nineteenth century mansion that was owned for a time by the Wong of Wong frozen foods. It was originally a Decarie house.

Could we have a letter from somebody about how cute Bob was? (Still is, I presume.)

Very old houses are rare in New Brunswick. Almost all housing is of wood. It doesn’t last long. That, with our dense forest, makes us a Fort McMurray in waiting.

graeme

It’s great to have these details, Graeme!

Bob Carswell and I are working on a map and a text that tells the story of Saraguay from around the 1930s to the 1960s and beyond. At a recent get together for coffee, I took a photo of him and as I did, I caught a fleeting expression of his that reminded me of a characteristic expression of his from about sixty years ago.

There was an old house on a street I think to the east of Lavigne St. in Montreal, between de Salaberry and Forbes, that as I think about it now may have been a building from the farm era, before that part of Cartierville was developed as a subdivision starting I guess around the early or mid-1950s. I imagine it was demolished by the late 1950s or early 1960s.

I worked for a while at a school – Saranac School – in North York, in the early and mid-1980s. It was near Lawrence Ave. and Bathurst, where a plaza was located at the time. Years later, a friend told me that as a kid (I guess in the 1950s), he and his friends used to steal apples from the apple orchard that used to exist where the plaza is now – part of a farm, I imagine – up until the 1950s.

I’ve told this story before, maybe even at this website. Anyway, I tell it again. When I worked at a school in Mississauga in the mid 1990s into the mid-2000s, the school was located where an apple orchard, part of some farm, perhaps, used to also exist, before the school was built.

I’ve noticed that trying to figure out local history can be tricky, as the writing of local history may not be in the hands of professional historians, meaning that information can at times be hearsay or conjecture, without much evidence of fact-checking or corroboration from multiple, reliable sources.

The archives, if available, that deal with local history can be useful, if a person has the time to wander through them, although I’ve noticed that even with archives, at times the details (e.g. the year in which a given building, depicted in an archival photo, was demolished) can be inaccurate.

Of course, national histories by professional historians can also show characteristics where it’s not always easy to distinguish between rhetoric and reality, between rumour (or conjecture) and fact. Even if there is agreement about basic facts, the framing of them can diverge, when differing accounts are compared. I guess one can say that the past is on many levels an imagined territory.