Enthusiasm for local history is not enough, by itself, to preserve and repurpose heritage buildings

I recently had the opportunity to offer input as part of Heritage Toronto’s Stakeholder Consultations. Below is a text of my comments. I have lightly edited the original text, to correct typos and tighten up or revise some of the wording.

Comments related to Sept. 26, 2018 Heritage Toronto presentation at Toronto Archives

I had signed up to attend the consultation session at the Toronto Archives on Sept. 26, 2018. However, our family has recently been renting a cottage north of Peterborough, and a five-hour drive, to and from Toronto was in the end too much for me. My input is thus restricted to the following comments.

From my perspective as a blogger, in this case as a former Toronto resident who still blogs about Toronto happenings, stakeholder consultations such as the one currently underway at Heritage Toronto are tremendously valuable – including for stakeholders, who have the opportunity to organize their thoughts, regarding relevant topics under review.

Neighbourhood Character Guidelines

I have read with interest the PDF document entitled “State of Heritage Report – Stakeholder Consultations – Toronto Archives – Sept. 26, 2018.”

The document refers to recommendations from a 2015 Report, which notes that dissenting opinion persists on whether Heritage Conservation Districts are “the right preservation tool to apply across the city.”

My sense is that HDCs are great under suitable conditions but I don’t see them being applied wholesale. I can share my own anecdotal experiences, from the years I lived in Long Branch.

In about 2012, I was persuaded to consider the idea of working with fellow residents to set up an HCD in Long Branch. I researched the matter at some length, and attended a weekend seminar in Stratford to learn as much as I could about how best to go about setting up such a district.

However, I decided in the end not to get involved in attempting to launch an HCD project in Long Branch. I had previously been involved in the successful launch of several community-based projects, at the national and international levels, but my sense was that the necessary conditions for a successful launch were not, in this case, in place.

More recently, I joined other residents on Villa Road in Long Branch, where we were living at the time, in exploring whether a Heritage Conservation District could be set up specifically for our street. However, the residents could not agree regarding the pursuit of an HCD designation, and the idea was dropped.

I believe, based on my anecdotal observations, that neighbourhood character guidelines, of the kind that have been developed in Long Branch as a pilot project, would be a more realistic tool to apply across the city’s neighbourhoods. The intent would be to focus on preservation of the physical character of neighbourhoods, as redevelopment of the existing housing stock proceeds.

The plan, as I understand from communications from the city, is for such character guidelines to be developed across Toronto, in each case taking account, with input from local residents and developers, of the unique character of each neighbourhood

In recent years, I have documented, at my Preserved Stories website, the development of the Long Branch Character Guidelines. The guidelines actually might, over time, come to play a significant role in local land-use planning decisions. Ideally, such guidelines would take into account the interests of both local residents and developers. Whether or not such a role emerges, for the character guidelines, remains to be seen.

From my observations, development of character guidelines benefits tremendously, from having a strong community association in place. The Long Branch Neighbourhood Association, for example, played a key role in development of guidelines in Long Branch.

In my experience, it’s important to do extensive planning – including getting extensive resident input in development of a mission statement and constitution – before the launch of such associations. It’s also imperative that leadership succession is built into the culture of the association, right from the start.

I strongly recommend support, on the part of Heritage Toronto, for the development of neighbourhood character guidelines across the city, and for building and maintenance of strong, broadly representative community associations, in all neighbourhoods across Toronto.

Strategic thinking in many cases matters more than huge budgets

The 2015 report refers to a lack of funding. In the current climate, the lack of funding is a given. The matter is expressed eloquently in a recent study, “Small Cities, Big Issues” (2018), edited by Christopher Walmsley and Terry Kading, which outlines the current climate aptly in a passage (p. 4) that reads:

“In Canada, as elsewhere, lower taxes, balanced budgets, an entrepreneurial environment, reduced government regulation, and the philosophy of small government have become the defining themes of governance. Following the federal lead, provincial governments have endorsed these themes and have oriented their policies towards increasing private sector investment and creating joint private-public sector initiatives. At its core, neoliberal policy aims to restore the profitability of the private sector – banks, corporations, local business initiatives – in response to the global economic problems that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s: high inflation and high unemployment, low or negative rates of growth, and rapidly accumulating government deficits. Neoliberalism seeks to address these problems by opening up new investment and consumption possibilities that are less constrained by government regulations and the limits of national markets (see Shutt 2005, 34-44).”

Lack of funding for matters such as heritage preservation – with rare exceptions where a readily evident economic payoff is envisaged – is a key feature of the neoliberal philosophy that has taken hold since the 1980s, in Canada particularly at the provincial and federal levels, with predictable consequences for municipalities.

A change in such a state of affairs is likely to come from within the global neoliberal mainstream, from individuals and groups with high levels of human capital, who have the capacity to perceive that the current state of affairs, if it continues, will be disastrous even for the apparent “winners” of the current state of affairs.

Attempts to challenge the neoliberal system from the outside are unlikely to succeed, given that each significant expression of a critical stance is incorporated at once into the ongoing system. A study entitled “The Rebel Sell” (2004) by Joseph Heath and Andrew Potter aptly outlines the latter point.

Like other volunteers involved in community organizing, I’ve achieved impressive results working with large numbers of other people in pursuit of shared goals. Huge budgets aren’t going to solve the problems that we face. Strategic thinking and skills in areas such as data analysis in many cases counts for much more than the availability of huge amounts of funding.

That said, you can’t restore and repurpose heritage buildings without spending money. An instance where money is being well spent is in Mississauga, with the Small Arms Inspection Building project, which I will outline below.

Leadership succession, and outreach to younger generations

The survey described in the Sept. 26, 2018 document is of interest. It’s vital to know what people think, and to know what inspires them. With regard to surveys, in my experience a key requirement is that public opinion expertise is brought to the table, in the design of such instruments. The survey in question, while interesting, has given rise to what can be described as rather vague generalities. A better-designed survey might yield more specific, and actionable results.

I would add, however, that I speak as a non-expert with regard to surveys. Maybe the survey in question was prepared by a top-rate survey professional, in which case my comments are wildly off the mark.

Some decades ago, I had designed a survey for a panel discussion that I had helped to organize. A friend of mine, who had just attended a course in survey design, said, “You don’t know anything about surveys.” I agreed he had a good point.

From that point on, in the projects we were working on (such as organizing of national conferences), we made it a point to persuade a public opinion professional (helping us as a volunteer) to help us with design and analysis of our surveys.

That made a most impressive difference. We acquired detailed information that helped us organize conferences, and we were able to continuously get better in our efforts as conference organizers, from one conference to the next, based on detailed feedback from conference goers, who filled out evaluation forms designed by a survey professional.

General comments regarding the role that archives play

I am a retired elementary school teacher. Since 2012, I have been involved with blogging about local history and cultures of land-use decision making, with a focus on Etobicoke and Mississauga waterfront neighbourhoods.

In 2011 I collaborated with fellow residents in a successful effort to keep a local public school, Parkview School in Long Branch, where I’ve lived for 21 years, in public hands. As a result of the Parkview project, I became interested in local history.

Uses and abuses of history

From what I can gather, history can be harnessed in service of community interests, and in service of the common good. History can, as well, be weaponized, twisted, and denied – and its archival resources can be destroyed.

I am sharing my thoughts as a former resident of Toronto. We lived in Long Branch for 21 years before selling our house in Long Branch and buying a heritage house in Stratford, Ontario.

In my comments about heritage preservation in Toronto, I will begin by sharing four stories

1. Archival research and storytelling call for vastly different skills

[Update: By way of an update to the following remarks, I would revise what I have said below by noting that, in many cases, people with skills in archival research are also incredibly fine writers and presenters. It’s taken me a while to arrive at this recent conclusion, which is based on my own anecdotal observations over the years.]

The first story concerns the Toronto Sun, where I did freelance work in the 1970s, ghostwriting articles for a consumer-advice columnist. Under her direction, I researched and wrote her columns.

At an early meeting, she advised me on how best to go about ghostwriting a consumer-advice article. In those pre-internet days, to write such a consumer column, you had two choices. You could go to a library, or you could do interviews.

The columnist said, and I paraphrase: “Don’t waste time sitting in a library. The text you come up with will lie flat on the page. Nobody’s going to read it. Instead, interview experts, people who know what they’re talking about. Then when you write your text, use their language, and their way of speaking. Your words will spring to life!”

She also told me that the first sentence in an article is there just to get attention. The lead sentence need not have anything to do with the rest of the article. I thought that was a clever observation.

I followed her directions. I never set foot in a library. I talked to a lot of interesting people, who knew what they were talking about.

I’ve interviewed many Long Branch residents, to get their stories about local history. To learn about local history, I made a point of interviewing long-time residents, rather than spending time in archives. From what I’ve observed, some seekers of local history can, metaphorically speaking, get lost in archives.

I’m reminded of a song from 1962 by The Kingston Trio, entitled “The Man Who Never Returned.” The song is about a man named Charlie who got on the Boston subway. The story is that the man got stuck riding back and forth forever on the train, with no way to get back home. Every day, the song narrates, Charlie’s wife hands him a sandwich through the open window, but he can’t get off the train.

I will, in fact, be doing archival research myself, to round out a book based on oral history interviews that I’ve recorded, in order to corroborate the information that oral history interviews provide. Given that memories, as research on this topic indicates, are malleable, details shared in such interviews need to be checked against archival sources.

On reflection, I would say that the advice from a Toronto Sun columnist, shared with me 40 years ago, was helpful but it wasn’t the final word. In the case of the Parkview story, which follows below, if we had gone out and just interviewed people, the project would have gone south fast. In this case, it was archival research that saved the day.

2. The Parkview School project in Long Branch convinced me that archives could be put to good use

The second story concerns what I learned in 2011 in a project related to Parkview School – now named École élémentaire Micheline-Saint-Cyr – at 85 Forty First St. close to the Long Branch GO station.

In this case, I learned that city and provincial archives could readily be used to advance the interests of local residents. Details about the effort to keep Parkview School in public hands are available at the Preserved Stories website.

Evidence from a preliminary archaeological dig, in 1984 at the school site, and archival evidence shared by two Toronto archival enthusiasts, played a key role in the Parkview project.

Archival evidence, directly related to the school site, enabled local residents to shape a compelling story, persuading provincial decisions makers to release $5.2-million to enable the school to be sold by one school board to another.

This meant the school would not be sold to a developer, who would have demolished the school building – as Colonel Samuel Smith’s log cabin, built in 1797 at a location where the Parkview school grounds now stand, had been demolished in 1955 – to make room for condos or townhouses.

The school grounds now remain as an inviting, beautifully situated green space where children and adults and their dogs can walk across and play in, at all seasons of the year. The school building, designed by a local architect to accommodate Baby Boom children, is now in full use as a French-language elementary school.

In this case, archaeological, historical, and archival evidence, crafted into a one-page template of a letter, sent out (in some cases in a personalized format) by hundreds of residents, in a two-stage, letter-writing campaign, saved the day – at least as seen from the perspective of everyday local residents.

3. Enthusiasm for local history is not enough, by itself, to preserve and repurpose heritage buildings

Persons with a strong interest in local history will achieve very little, in my anecdotal observation, in saving landmark heritage buildings unless they work in alignment with individuals skilled in marketing, event planning, community organizing, and media relations.

The preservation and repurposing of the Small Arms Inspection Building in Mississauga, a project explored at length over several years at my website, is a case study in the effective application of the above-noted skills. I could cite a couple of instances in south Etobicoke where persons without such skills have attempted to engage in heritage-preservation projects but have not achieved the desired results.

What would have been required, in my anecdotal observation, would have been a more extensive set of skills; where there is a clear procedure in place, for arriving at decisions; and where each participant demonstrates a strong capacity to work together, in close collaboration with other members of the project team.

These are also the conditions that must be met, in the event that people want to undertake a successful Heritage Conservation District designation, for a particular patch of neighbourhood.

I have seen those conditions being met with regard to the successful – and widely celebrated – designation of individual heritage buildings under the Ontario Heritage Act. The latter designation carries some weight. Having a building on a city heritage registry may or may not carry weight, depending on circumstances, from what I have observed.

4. Human capital (which includes the capacity to ask questions) plays a key role in effective participation in local land-use decision-making

My fourth story concerns my anecdotal observations as a blogger, reporting on public meetings in Toronto and Mississauga.

As I’ve noted at my website and at an Etobicoke Guardian opinion article, on April 4, 2018 I attended a meeting organized by the Long Branch Neighbourhood Association, at which city staffers spoke about how the Long Branch Character Guidelines may, or may not, affect future land-use planning decisions in Long Branch.

At that meeting, I was most interested to learn that, according to two city staffers, I was not permitted to record what city officials said at the meeting, nor was I permitted to post any direct quotations of what staff said at the meeting, based on my notes, without first getting permission from media relations at the City of Toronto.

After the meeting, I contacted media relations and asked if the above-noted prohibition was, in fact, City of Toronto policy. Among other things, I asked: “Does a person need to get permission from the city before remarks by city staff at a public meeting can be recorded?”

The answer was: “No. Information provided by city staff to the public at a public meeting is a matter of public record. As a courtesy, you may want to advise staff that you are present as a blogger or member of the media but that is not a requirement.”

The bottom line is: If a person is in doubt about a statement, by any person regarding any topic, it’s a great idea to seek verification of it. A corollary is that, when working with city staff, it makes sense to proceed with care. Otherwise, you may lose your way.

In the rest of my comments, I will address topics that are related to the four above-mentioned stories.

Are artifacts from Toronto’s geographical margins of interest to the Toronto Archives?

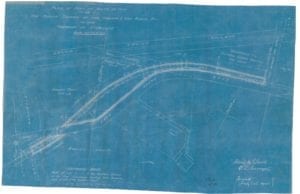

Right of way map, 1905, featuring site on which Colonel Samuel Smith built a log cabin in 1797 in his capacity s the first European settler-society landowner in Long Branch. Source: Private family collection

A year after the Parkview project, I set up a website and began to write about local history. After I was contacted by an elderly former resident of Long Branch, I became aware of an impressive collection of historical documents, related to the George Eastwood family, some dating back to the early 1800s (as I recall, at any rate) and a trophy from a 1920s horse show, connected with the former owners of the Parkview School property.

The artifacts also include a “right of way map” dating from 1905, which I have posted to my website in connection with a report on one of my oral history interviews with long-time residents.

Possibly the Toronto Archives will serve as a suitable destination for the above-noted documents. That remains to be seen.

From my discussions, some years ago, with a Toronto Archives staffer, I concluded that the above-noted Eastwood documents might not be of much interest to the city archives. As a next step, however, I will digitize the documents and share the files with archives, to see if the files will permit a more complete assessment than available from my verbal description of the documents. There are many options, with regard to which archives are best suited for a given set of documents.

In general terms, archives can play and important role in everyday life, as the Parkview School story underlines.

They have value to the extent they are used – to the extent that a use for them is found, in the present moment, and to the extent that the ability for someone to use them, in a future present moment perhaps hundreds of years hence, is retained.

History can be used in service of democracy, or it can be used in service of fascism

History and the artifacts related to can readily be used in the service of everyday community interests in a democratic society – or they can be used in the service of ideological interests including, for example, fascism.

On this topic, many resources are available. My own recent reading has included, for example, the May-August 2018 issue of a scholarly journal entitled New Eastern Europe.

How to set up your own para-state

By way of illustration, an article in the latter publication, entitled “How to set up your own para-state,” by Pawel Pienazek, a Polish journalist based in Syria, notes that the building of a suitable narrative is central to the setting up of a para-state (that is, an unrecognized state) in any unsettled region of the world. The article notes, as well, that nostalgia is important for the narrative.

As Pawel Pienazek notes: “The desire to return to the past – or, more precisely, its ideological reinterpretation – is a factor driving many societies around the world” (New Eastern Europe, May-August 2018, p. 23).

The writer adds (p. 23): “Before the ‘zero hour’ comes [whereby a para-state is launched], you need to have visuals ready. Flags, symbols, and the image of a strongman leader are always a great start. He – it is nearly always a he – should have a threatening but approachable face that people should fear and admire at the same time.”

How can we best preserve and celebrate collective memory?

Another passage (pp. 168-9) comes to mind as well, from an article by Mateusz Mazzini in the same journal, about contemporary Poland, entitled, “Memory of independence: A gap-filling exercise”; the article notes that:

“A similar critical decomposition can be conducted with regard to collective memory, a notion of paramount importance in the context of the independence commemorations. ‘Collectivities have memories, just like they have identities:’ wrote the American sociologist Jeffrey Olick in his famous essay ‘Collective memory: The Two Cultures’’. Moreover, collective memory is not only inherently plural, or, as Richard Kravitzek put it, polyphonic, but also multidirectional. The latter term, particularly popular and prolific in the Polish school of memory studies, as illustrated in the works of Barbara Szacka and more recently Joanna Tokarska-Baldr, is perhaps the most important for the entire debate over the ways of commemorating independence.

“The multidirectional nature of memory allows for its development alongside numerous paths simultaneously. In simpler terms, the creation of narratives related to one particular historical event or phenomenon does not exclude a parallel creation of narratives concerning a different fragment of the collective past. From this angle, collective memory is a building under construction, of which different wings can be developed, expanded and built over at the same time. An expansion of the memory of independence therefore does not need to be synonymous with abandoning other commemorative efforts.”

A lack of archival resources can prompt us to seek out information about the past in other ways

From the above-noted four stories based on my own anecdotal experiences, some additional thoughts emerge.

At the time of the Parkview project, I learned that there is little information about Colonel Samuel Smith, in archives or in the historical record in general. I found that an intriguing state of affairs. Little is know about his personality, or activities, from the historical record. To learn more about his life, I decided to learn as much as I could about the times he lived in. I began to read extensively about the British empire, colonial history, and military history.

Having read widely about the times he lived in, I now have a better sense of who the colonel was, and how his life fit into the larger scheme of things.

What to do after archives are destroyed?

A community-resourced art initiative is outlined, in an article entitled “Culture in a conflicted region,” in the May-August 2018 issue of New Eastern Europe. The following passage (pp. 37-38) describes one way to address a situation where archives get destroyed.

“The residence project was initiated by Rossman-Kiss. He proposed a unifying theme for the first year of work – ‘archive’’. It is connected to the story of the national archive that was burned down by Georgian troops when they occupied Sukhum during the Georgian-Abkhaz war. The destruction of the state archive is a tragic moment in the history of Abkhazia and is perceived as an attempt to deprive the Abkhazians of their memory.

“Within the framework of the residence programme, Rossman-Kiss implemented the first participatory art project in the history of Abkhazia –

a multimedia installation titled Memory, Untitled dedicated to the destiny of the destroyed national archive. Direct participation, of the audience in the process of the work minimises the distance between the audience and the artist, between art and life. The residents of the country were invited to send their memories – anything that was significant for them and connected with Abkhazia. This call was regularly broadcasted by one of the partners of SKLAD, the Sukhum-based SOMA FM radio station. ‘The world deserves to know Abkhazia and Abkhazia deserves to know the world. Abkhazia will only benefit if it opens to the world. A metaphoric reconstruction of an archival space incorporates memories submitted by locals through an open call, historical videos, audio and photographic footage as well as descriptions of dreams. Underlined by a multi-layered soundtrack, this complex material is dispersed between two screens, three monitors, shelves and library catalogue cards and card holders; the different methods of classification and presentation echo multiplicity of voices and materials found in any archive. The space created is intimate and universal, comforting and troubling – thus allowing visitors to explore it freely depending on their own interests and rhythm:’ This is how the Swiss artist described his multimedia project.”

Whether stories are based on evidence or falsehoods, framing drives history-related story-construction

A basic precept, with regard to quality journalism, is that evidence matters. Verification and corroboration related to contents of news reports are feature of responsible reporting.

In all storytelling – whether based on evidence, or on falsehoods – the framing of the story shapes its impact.

Framing concerns itself with how facts and evidence – as well as falsehoods – are managed in the service of messaging.

Many of life’s key messages must, for reasons of communications effectiveness, be stated succinctly, and in a way that gives rise to an emotional response.

Succinctness entails condensing.

In condensing information, in order to build a suitable frame or context for the presentation of it, we emphasize some things, and omit others.

By way of illustration, when I give talks to local audiences about local history, I usually condense a vast amount of corroborated information into two or three key points that I wish to focus upon.

Often, I will include a few words of gossip related to some character from local history, as otherwise people fall asleep. That is my particular way of condensing data, and focusing on emotion, in a presentation.

If I share the same story about local history in a blog, however, I will use other ways, than gossip, to maintain the interest of the reader. I will approach things differently, because the requirements of written texts differ from those of oral presentations. The spoken word, unless its recorded, is also less permanent than the written one.

Serious writing of history entails a particular relationship to archives

A professional, in-depth familiarity with archival resources – and skill in historical analysis and research – are necessary, in my experience as a reader, in order to present an account of history that corresponds with the values of a democratic society.

At one end of a continuum, in the writing of history, is the amateur historian, focusing on local history for a limited audience, who gets facts mixed up and promotes the spread of urban legends, that have no basis in fact. Whether or not the facts are correct is not of great concern for anybody, in such a form of local-history storytelling, from what I can gather. Occasionally, such amateur historians contribute materials to archives, which can give rise to problems related to accuracy.

The colonel’s cabin was torn down in 1955

By way of example, as I’ve outlined in an overview entitled, “The History of Long Branch” at the Preserved Stories website, the Colonel Samuel Smith log cabin (to which extensions and siding had been added over many years) was torn down in 1955, not in 1952.

Some photos of the Samuel Smith house, taken before it was torn down, are available at Montgomery’s Inn. The captions, written by an amateur historian who provided the photos, erroneously claim that the building was torn down in 1952. Contemporary newspaper accounts, and other evidence, underline that it was in fact demolished in 1955.

Nonetheless, many online and printed sources claim the event occurred in 1952. The false date in each case is repeated because the person who repeats it does not seek out verification of it, by referring to relevant sources. In some cases, this happens because time is short. In other cases, a person may be unfamiliar with the practice of fact checking.

The Long Branch Hotel burned down in 1958

By way of conclusion, I refer to the Long Branch Hotel. This impressive former Long Branch landmark was built on land that the Colonel Samuel Smith family had sold to George Eastwood. In the late 1800s, Eastwood sold a portion of the property to a developer, who opened up a high-end “cottage country” resort. The hotel, which had served as a centrepiece of the resort, burned down in 1958, as newspaper accounts and first-hand observations (including by people that I’ve interviewed) have confirmed. Online and printed sources, however, widely circulated, continue to claim that the event took place in 1954.

That concludes my comments. I much appreciate the chance to share them.

Another one happened this June. Marie Curtis house at 10-31st was torn down. Built in 1927 it is where she lived while the Reeve of Long Branch. It was totally intact. There was zero interest from either the Committee of Adjustment or the Long Branch community to preserve her house until after it was torn down.

That is for certain part of the story of Long Branch. What remains of her legacy is the name of the nearby, celebrated park and stories about her. Among the stories, the accuracy of which I cannot vouch for, as I do not currently have a way to verify or corroborate them, are the following:

Many years ago, so the story goes, a meeting was held with the intention of closing down the Long Branch Public Library, a building designed by a Long Branch architect of a previous era, who had also designed the former Parkview School, the current version of James S. Bell school, and several small buildings at Marie Curtis Park along Forty Second Street.

Anyway, the story goes that, at the meeting, the discussion was about the closing of the library. An older woman, very formidable in her demeanour, who as it turns out was Marie Curtis, walked up to the front of the meeting. She spoke, as I understand, in a manner that held the close attention of those in attendance. She explained why, in her view, the library deserved to stay open. Open it remains, to this day.

A second story concerns a meeting at which Frederick G. Gardiner and Marie Curtis were both present. At one point, Gardiner remarks, so the story goes, that for a person of such a short stature, Curtis has a big mouth, as she is always speaking out. To which Curtis is said to have responded, and I paraphrase, “I may be small of stature, Fred, but I was elected to the office that I hold. I wasn’t appointed, as was the case with you.”

The architect I refer to is Gresely Elton, highlighted at previous posts including:

Elton Crescent in Long Branch is named after J.O. Elton, reeve of Long Branch and brother of architect Gresely Elton

Some years ago, on a couple of occasions, I interviewed Jane Olvet of Oakville, daughter of Gresely Elton, who told me about how her mother and father first met, in the early 1900s at a Long Branch Park tennis court – not that far from where Marie Curtis once lived. The following post refers to the tennis court:

Sixth Stop: Parking Lot where Long Branch Park Tennis Court stood at Thirty Third St.: May 5, 2018 “Evolution of Long Branch Park” Jane’s Walk

My first video recorded interview with Jane Olvet took place some years before I developed a real interest in the local history of Long Branch. At that time, when Jane and Sid Olvet visited us in Long Branch, I was so taken with Jane’s stories about life in Long Branch many, many years ago that I felt that it would be a great idea to record some of her stories and reflections.

These recordings are among the large stock of audio and video recordings that I will be working with, through a process of editing, transcribing, and in other ways processing, in my “writer’s retreat” in Stratford.

What really struck me, from the first interview with Jane Olvet many years, was her remark that, for many years, she didn’t want to talk about Long Branch. So many people, including her parents, were now gone, with the passage of the years. On that visit to Long Branch, we walked up and down the streets, and Jane pointed out who had lived where, and she spoke of the pathways through open fields that she took to go to and from school each day.

For some days after recording my interviews with Jane Olvet that day, the following thought lingered in my mind, and stayed with me, in a powerful way. The thought was, and I paraphrase: “It’s really remarkable, how much has come and gone, in this community as in any other. Relatively speaking, we are on this earth for such a short time. Lives are fleeting. All things come and go.”