History of Ontario includes Indigenous history

I recently bought a copy of All Our Relations: Finding the Path Forward (2018) by Tanya Talaga.

I look forward, as well, to reading Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death, and Hard Truths in a Northern City (2017) by Tanya Talaga.

European settler history is closely related to the history of urban spaces and rural landscapes in Southwestern Ontario.

I have accumulated many first-hand impressions based on travels in Ontario and elsewhere. I’ve also been searching for library books about the history of small cities and physical and cultural landscapes in Southwestern Ontario.

For many years, I was involved (along with my friend Mike James) with leading and/or organizing Jane’s Walks in Long Branch and nearby neighbourhoods.

I now go for walks in Stratford and also talk with long-time residents, learning about local history.

Indigenous history of Ontario

First Nations history and settler history are closely intertwined.

Both settler history and Indigenous history includes study of diasporas – including diasporas connected with settler migrations, and internal diasporas arising from settler-initiated extermination and displacement of Indigenous peoples.

The latter processes are outlined in a study entitled The Great Land Rush and the Making of the Modern World, 1650-1900 (2003) by John C. Weaver. An excerpt from a blurb for the latter study reads:

Weaver shows that the enormous efforts involved in defining and registering large numbers of newly carved-out parcels of property for reallocation during the Great Land Rush were instrumental in the emergence of much stronger concepts of property rights and argues that this period was marked by a complete disregard for previous notions of restraint on dreams of unlimited material possibility.

For the current post, I’ve listed a number of studies related to First Nations history in Ontario and elsewhere.

Earlier accounts of European settler history around the world, written on behalf of settler interests, have tended to distort, denigrate, or ignore the history of Indigenous peoples. However, more recent, evidence-based studies, which among other things seek to take into account Indigenous sources and perspectives, are available.

I’ve written previously about the Oka crisis in Quebec.

For each book below, I’ve included a short excerpt from a blurb (or in some cases a complete blurb) for each respective study.

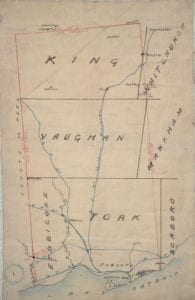

The image is from the Toronto Public Library website. Caption pasted on: “Original Plan of the Toronto Purchase from the Indians, 1787-1805. Showing the 250,808 acres, of which Toronto occupies (1911) 10,477, sold by the Indians to the Government for $9,500.” The plan is from the J. Ross Robertson Collection of maps.

The First Nations of Ontario: Social and Historical Transitions (2017)

Edward J. Helicon

The author examines historical transitions and contemporary conditions, covering such topics as treaties, the archaeology of the Province of Ontario, neo-colonial trends, restorative justice, and the present challenges facing the Indigenous population.

Karl S. Hele – editor

Explores the power of Nature and the attempts by Empires (United States, Canada, and Britain) to control it from Indigenous or Indigenous influenced perspectives. This title hopes to inspire ways of looking at the Great Lakes watershed and the people and empires contained within it.

Ipperwash: The tragic Failure of Canada’s Aboriginal Policy (2013)

Edward J. Hedican

On September 6, 1995, Dudley George was shot by Ontario Provincial Police officer Kenneth Deane. He died shortly after midnight the next day. George had been participating in a protest over land claims in Ipperwash Provincial Park, which had been expropriated from the native Ojibwe after the Second World War. A confrontation erupted between members of the Stoney Point and Kettle Point Bands and officers of the OPP’s Emergency Response Team, which had been instructed to use necessary force to disband the protest by Premier Mike Harris’s government. George’s death and the grievous mishandling of the protest led to the 2007 Ipperwash Inquiry.

No Place for Fairness: Indigenous Land Rights and Policy in the Bear Island Case and Beyond (2009)

David McNab

McNab provides details of how ministers and their senior officials resisted real efforts to resolve problems as well as examples of field staff resisting government attempts at resolution. He also shows that government entities such as the Indian Commission of Ontario and the Native Affairs Directorate were largely used as ‘mailboxes’ where successive federal and provincial governments sent things they wanted to bury. No Place for Fairness is the story of what happens when Aboriginal peoples’ political rights are crammed into the Euro-Canadian legal system.

Circles of Time: Aboriginal Land Rights and Resistance in Ontario (1998)

David McNab

Controversial decisions such as the Temagami case and Oka are detailed, and McNab, who draws on archival sources that support oral history, provides a new perspective on land claims issues. Such compelling background information will be invaluable to anyone endeavoring to understand the origin and the current controversies surrounding Aboriginal land and treaty rights, and will clarify the reasons for resistance. Above all, this book will remind us we must never forget that this history belongs to Aboriginal people. Turtle Island is their place, and their oral history can no longer be ignored.

Indigenous history of North America

An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian catastrophe, 1846-1873 (2016)

Benjamin Madley

Madley describes pre-contact California and precursors to the genocide before explaining how the Gold Rush stirred vigilante violence against California Indians. He narrates the rise of a state-sanctioned killing machine and the broad societal, judicial, and political support for genocide. Many participated: vigilantes, volunteer state militiamen, U.S. Army soldiers, U.S. congressmen, California governors, and others. Ultimately, the state and federal governments spent at least $1,700,000 on campaigns against California Indians. Besides evaluating government officials’ culpability, Madley considers why the slaughter constituted genocide and how other possible genocides within and beyond the Americas might be investigated using the methods presented in this groundbreaking book.

An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (2014)

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

In An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, Dunbar-Ortiz adroitly challenges the founding myth of the United States and shows how policy against the Indigenous peoples was colonialist and designed to seize the territories of the original inhabitants, displacing or eliminating them. And as Dunbar-Ortiz reveals, this policy was praised in popular culture, through writers like James Fenimore Cooper and Walt Whitman, and in the highest offices of government and the military. Shockingly, as the genocidal policy reached its zenith under President Andrew Jackson, its ruthlessness was best articulated by US Army general Thomas S. Jesup, who, in 1836, wrote of the Seminoles: ‘The country can be rid of them only by exterminating them.

Some comments in the book about the history of Afghanistan are off the mark, in my view. However, such points aside, the book warrants reading.

Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (2013)

James W. Daschuk

Clearing the Plains is a tour de force that dismantles and destroys the view that Canada has a special claim to humanity in its treatment of indigenous peoples. Daschuk shows how infectious disease and state-supported starvation combined to create a creeping, relentless catastrophe that persists to the present day. The prose is gripping, the analysis is incisive, and the narrative is so chilling that it leaves its reader stunned and disturbed. For days after reading it, I was unable to shake a profound sense of sorrow. This is fearless, evidence-driven history at its finest.

The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing (2005)

Michael Mann

Mann demonstrates how colonial cleansings of the aboriginal peoples in Spanish Mexico, the US, Australia, and elsewhere represent the first dark side of emerging modern democracies, but he primarily focuses on the process of genocide in Armenia, Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, China, Cambodia, Yugoslavia, and Rwanda. After examining the background, motives, and roles of perpetrating political elites, state officials, soldiers, paramilitaries, and thugs in these mass murders, the author indicates that this dark side of democracy has finished passing through the north and is now engulfing parts of the Southern Hemisphere.

Of related interest

Origin of hockey

A Jan. 18, 2019 Acadiensis article is entitled: “Reimagining the Creation: The ‘Missing Indigenous Link’ in the Origins of Canadian Hockey.” An excerpt reads:

The game of hockey most likely began with the First Nations, the people known in the Maritime region as the Mi’kmaq, and its history is being pieced together by First Nations experts like Michael Robidoux, Roger Lewis and Bernie Francis utilizing insights and research gleaned from an intimate knowledge of Mi’kmaw language, culture, and ways.[4] That ground-breaking research will continue to focus on authenticating the existence of an early indigenous form of hockey in Mi’kmaki.

“Seventy percent of children in Nunavut go to bed hungry”

A CBC Second Opinion article, accessed Jan. 12, 2019, is entitled: “The dark side of Canada’s new food guide.” An excerpt reads:

Seventy percent of children in Nunavut go to bed hungry. I don’t think we can say that statistic often enough.

Indigenous leadership

A Jan. 11, 2019 Winnipeg Free Press article is entitled: “Wet’suwet’en is a reminder this isn’t a nation-to-nation relationship.”

An excerpt reads:

The Wet’suwet’en situation is a microcosm of the biggest challenge facing healthy relationships between Indigenous nations and Canada.

A Jan. 11, 2019 CBC article is entitled: “Why the RCMP may not be a neutral player in the Wet’suwet’en anti-pipeline dispute.”

The opening paragraphs read:

Clashes between anti-pipeline protestors and the RCMP earlier this week in the traditional territories of the Wet’suwet’en nation may have been years in the making, according to criminologist Jeffrey Monaghan.

The Carleton University professor says the RCMP has been fixated on the Unist’ot’en clan — who are at the center of this week’s dispute — since at least 2011.

Through Access to Information requests, Monaghan has uncovered a number of official government documents that he believes reveal consistent bias against members of the Wet’suwet’en anti-pipeline movement.

[End of excerpt]

Healing crystals

A Jan. 4, 2019 CBC article is entitled: “Healing crystals are sold as wellness products, but they can have shady origins.”

An excerpt reads:

A lot of the crystals do come from mines here in America, but they come from mines that we know have had a lot of environmental violations — like, say, having mine runoff pollute the local water source of a Native American community. So there’s a lack of regulation on both sides: labour and environmental.

A Sept. 17, 2019 Guardian article is entitled: “Dark crystals: the brutal reality behind a booming wellness craze: Demand for ‘healing’ crystals is soaring – but many are mined in deadly conditions in one of the world’s poorest countries. And there is little evidence that this billion-dollar industry is cleaning up its act.”

Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada

An Oct. 18, 2018 CBC article is entitled: “Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada.”

An excerpt reads:

This ambitious and unprecedented project inspired by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action. Exploring themes of language, demographics, economy, environment and culture, with in-depth coverage of treaties and residential schools, these are stories of Canada’s Indigenous Peoples, told in detailed maps and rich narratives.

Mining

A March 3, 2017 Guardian article is entitled: “Toronto’s buried history: the dark story of how mining built a city.”

An excerpt reads:

It was Cobalt that solidified Toronto’s connection to the industry, bringing American and British capital into Canada en masse. In 1906, Ontario’s new Conservative government passed the Mines Act – an open-entry legislation that remains on the books today. This act allows mining companies to lay claim to minerals sitting under virtually all public land, some private land, and First Nations reserves.

An Oct. 8, 2019 London School of Economics article is entitled: “Book Review: The Global Interior: Mineral Frontiers and American Power by Megan Black.”

An excerpt reads:

Megan Black’s The Global Interior: Mineral Frontiers and American Power reveals a fundamental paradox in American global power—its imperial stature and its anticolonial legacy. From its founding in 1849 to the 1980s, the Department of the Interior has both ensured and obscured this powerful ambiguity. It played a pivotal role in facilitating the extraction of mineral wealth, rolling back environmental regulations and expanding the frontier to the seas and then into space. But the Department also developed water sanitation and irrigation in the Global South, promoted better agricultural methods, geological exploration and conservation programmes for soil, wildlife, forests and rivers. The Interior practised hard and soft power.

Black argues that the Department’s benevolence and conservationist actions were used as covers for the real desire of extracting mineral wealth. ‘The military-industrial complex and culture of consumer abundance converged to intensify federal anxieties about America’s mineral solvency’ (122). The choice of words is apt. Underlying much of this book is a sense of anxiety within American foreign policy—whether it’s the anxiety of white settlers holding onto land in the nineteenth century, fears that Latin America could withhold minerals during World War II or turn communist in the Cold War or the alarm that OPEC states could limit oil and gas production causing a spike in prices. We see that the Interior’s ‘mineral technocracy’ was foundational in maintaining American power projection across the globe.

An additional excerpt reads:

This, Black argues, reveals a founding myth of the Department—its denial of a global role. The American West was an internal colony that became a blueprint for the US in Latin America, Africa, Asia, the ocean and even in space. The Interior parcelled out frontier land, administered parts of Alaska and Hawaii before statehood, and the Caribbean and Pacific islands, too. The racial history of conquering the West shaped US legislation and attitudes to Filipinos, Cubans and Puerto Ricans (40). ‘Minerals were thus not just a straightforward motive for expansion, as historians overwhelming suggest; they were also a vital means for it’ (6). Each conquest led onto the next.

External and internal migration

A July 13, 2016 Atlantic article is entitled: “Champagne in the Cellar: How I used the internet to find the man who saved my parents’ lives in a Budapest basement during World War II.”

An excerpt reads:

The life of an immigrant is a life of two places, two identities. And maybe that’s especially so for those who feel they have no choice but to leave their native land.

Additional resources

A Concise History of Canada’s First Nations (2015)

Olive Patricia Dickason, author

William Newbigging, contributor

This fully updated edition is a brief but comprehensive overview of the long and vibrant history of Canada’s First Nations. From pre-contact and first encounters with Europeans to present struggles for self-determination, this engaging text offers a multifaceted account of Canada’s founding peoples.

Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times (2009)

Olive Patricia Dickason, author

David McNab, contributor

A central argument in the text is that Amerindians and Inuit have responded to persistent colonial pressures through attempts at co-operation, episodes of resistance, and politically sophisticated efforts to preserve their territory and culture. The fourth edition has been fully updated to include current topics such as the effects of global warming on the Innu, the Ipperwash Inquiry, and the Caledonia land claims dispute. This is a text that transcends the familiar and narrow focus on Native-White relations to identify the history of the First Nations as a separate and proud tradition.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!