Beyond Totalitarianism (2009) features specialist essays comparing Nazi and Stalinist mass murder in the 1930s and 1940s

Update: A recent article of interest is entitled: Crimes of the Wehrmacht: A Re-evaluation, by Alex J. Kay and David Stahel (2020), Journal of Perpetrator Research, 930, 1, 95-127.

https://jpr.winchesteruniversitypress.org/articles/10.21039/jpr.3.1.29

An excerpt (pp. 97-98) reads:

This brings us to a key argument overlooked in the current literature and the main focus of this article: the sheer brutality of the German conduct of war and occupation in the Soviet Union has overshadowed many activities that would otherwise be (rightly) held up as criminal acts. In identifying what might be categorised as ‘secondary crimes’, our understanding of what constituted criminal behaviour is enhanced, while the number of perpetrators is significantly expanded. As many of the examples below will reflect, such crimes often constituted a less overt breach of the international laws of war and, in some cases, exhibited a less direct relationship between the perpetrator’s action and the victim’s suffering, but these considerations do not ameliorate the criminal responsibility of the German soldiers involved. The examples – addressing sexual violence, theft and starvation, and coerced and forced labour – draw in part on recent advancements in scholarship, providing fresh insights into new areas of criminality, but are largely based on a reconceptualization of the day-to-day reality of life for the average Landser on the eastern front. After the discussion of different types of ‘secondary criminality’, this article examines the following aspects: first, the situational framework provided by environmental and institutional factors on the eastern front; second – in an excursus on major war crimes – the interaction between perpetrators and bystanders, and the role played by spectators in legitimising murders and other atrocities; finally, the importance of ideology, political ideas and National Socialist beliefs in the actions of the soldiers.

*

The comparative study of Nazi and Stalinist mass murder requires a strong conceptual framework. Otherwise, you are spinning your wheels and wasting time.

That is a key take-away from my reading of a chapter in Beyond Totalitarianism: Stalinism and Nazism Compared (2009).

Councillor Jim Tovey (1949-2018) speaking at May 28, 2016 Small Arms Jane’s Walk. Jim Tovey was a key player in saving the Small Arms Inspection Building in Mississauga from demolition and coordinating efforts to secure strong government and community support for its repurposing. Jaan Pill photo

I refer to chapter four, entitled: “State Violence – Violent Societies.”

I’ve also recently finished reading The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia (2017) by Masha Gessen. The latter book argues – the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 notwithstanding – that the government of Russia remains totalitarian, albeit in a form that differs, slightly, from the Stalinist regime of the 1930s and 1940s.

Assuming that the latter book’s definition of totalitarianism is accepted by readers, Gessen’s argument is compelling. I have turned to Beyond Totalitarianism (2009) because I want to get up to speed, as best I can, on current historiography as it relates to totalitarianism – as a concept, and, in particular, as an analytical concept.

That is, what do we mean when we speak about totalitarianism? And how useful is it as a term that seeks to explain what has happened in the past, and what is happening now?

Beyond Totalitarianism (2009) is aimed at more of a specialist audience, a smaller audience – whereas The Future is History (2017) is more for general readers, a larger audience. Books for larger audiences tend to present arguments in slightly simpler, less nuanced forms thereby reaching more readers. The general reader takes a stroll through the park. The specialist reader, on the other hand, may not find the slog, through a dense and intricate package of words, quite as easy going.

Jim Tovey did A-1 job hosting the only @Doors_OpenTO in @citymississauga (also known as the Small Arms Jane’s Walk) at the Small Arms Inspection Building in Mississauga! Jaan Pill photo

Of the two books about totalitarianism that I refer to at this post, I can say that each is a compelling read. From reading them, I have a better understanding of how things work in the world. For any book related to history, I want storytelling that connects at an emotional level, with its audience; I want reliable evidence that drives the story forward; and I want a conceptual framework that enables me to understand the meaning of the story. Depending on the intended audience and the quality of the editing, a given book may be more accomplished in some of these areas, and less in others.

Structure of Beyond Totalitarianism (2009)

Beyond Totalitarianism (2009) comprises a series of essays. Each chapter has two authors who are specialists, respectively, on Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia. In chapter four of the book, Christian Gerlach (specializing in history of Nazism) and Nicolas Werth (specializing in history of Stalinism) have responded to a series of questions from the editors, Michael Geyer and Shelia Fitzpatrick.

Ronnie the Bren Gun Girl: Veronica Foster. Source: Libraries & Archives of Canada PA – 119766. Veronica Foster was actually a non-smoker, her daughter informed me at a Small Arms Doors Open event some years ago. She only smoked for the photo session where this photo and others were taken.

Gerlach and Werth outline the questions (p. 138; I have added a paragraph break):

Our main questions for each participatory group are, Which interests and attitudes led to violence? Which institutional structures were involved? Which methods of violence were employed and to what extent? What role did public participation, consent, or dissent play? How important was “initiative from below” or impetus from the regions? And, finally, considering the above questions, how can the role of the state best be characterized?

In attempting to answer these questions, we compare mass violence against the following groups: so-called “asocials,” victims of ethnic resettlement, and prisoners of war during and after the Second World War.

As the authors note, the chapter focuses on the mass murder of “so-called ‘asocials,’ victims of ethnic resettlement, and prisoners of war during and after the Second World War.”

Chair of the Small Small Arms Society, Diane LaPointe-Kay, outlines options for repurposing of the Small Arms Inspection Building with a focus on the arts and a wide range of similar creative endeavours. Jaan Pill photo

According to chapter four, past attempts to compare Nazi and Stalinist mass violence have had “controversial outcomes” (p. 133). Consequently, the authors note, “some specific methodological reflections” are now required: “On this basis, we try to contribute a new and perhaps more conciliatory approach to the comparative study of violence.”

Existing studies of Stalinist and Nazi mass violence, the authors note, “focus on the Soviet and German camp systems, usually reducing the great variety of camps to a select ‘representative’ few on each side – namely, the concentration camps and the Gulag” (p. 133).

With reference to German perpetuators and functionaries involved with such violence, they add, “our concrete knowledge about perpetrator groups and individuals is sketchy, fragmentary, unbalanced, and still without a solid, agreed-upon theoretical framework. Furthermore, certain subject areas have been woefully neglected: little research has been conducted on German mass exterminations outside the Jewish Holocaust and the reasonably well-explored ‘euthanasia’ program, and an overall analysis of the different German policies of extermination within one framework remains to be undertaken” (p. 134).

We can say that, without a suitable analytical framework, valid comparisons are beyond the reach of historians, or anybody else.

The authors note that the new research, on behalf of which they advocate, “is not about discerning the one ‘true’ explanation; it is about elements of explanation. Rather than intellectual confusion, it reflects a new sense of complexity in our understanding of these events” (pp. 134-5).

May 28, 2016 Small Arms Jane’s Walk: On our way from the Small Arms Inspection Building to meet Kate Hayes of Credit Valley Conservation at the Lake Ontario shoreline, we stopped for a discussion about the wooden baffles at the Long Branch Rifle Ranges. In response to a question for a walk attendee, Jim Tovey (holding microphone) noted that the aim is to restore the Long Branch Rifle Ranges to a state approaching their original condition. Jaan Pill photo

As well, (p. 135; as elsewhere at this post, I have added paragraph breaks to the following quote) an

earlier assumed contradiction between ideologues and pragmatists in Nazi Germany appears out of date; instead, differences appear to have been only gradual, and cooperation between authorities more decisive than conflict. An increasing number of scholars further accept that ideology and economy were often mutually reinforcing, rather than opposing, forces.

As a result, German extermination policies can only be regarded as multicausal. Recognizing that a complex of alternatively reinforcing and competing factors and arguments resulted in the dynamics of destruction, the long-pursued search for the prioritarian factor appears unnecessary, even counterproductive. The interplay among political, economic, military, and other ‘pragmatic’ motives further questions the distinction often made between ‘ideological’ and ‘utilitarian’ mass extermination in genocide studies.

Wooden baffles such as this one served as sound barriers at the Long Branch Rifle Ranges. Jaan Pill photo

Having begun with an investigation into the Nazi system, historians of Nazi Germany are on their way to understanding an extremely violent society.

As I understand, the reference to “the prioritarian factor” refers to previous, failed attempts to find a single, overriding determinant of dynamics of Nazi mass murder.

Extremely violent societies

When I first came across the concept of “extremely violent societies,” a term that Christian Gerlach introduces in Extremely Violent Societies: Mass Violence in the Twentieth Century (2010), I pondered the concept:

Christian Gerlach’s 2010 genocide-related study focuses on extremely violent societies

It was of interest to encounter the term once again, this time in Beyond Totalitarianism (2009). I was interested to follow the build-up (pp. 136-7) in chapter four which leads the authors to reject totalitarianism as a conceptual framework for engaging in comparative history:

Comparative analyses allow us to locate parallel and/or contradictory developments in analogous situations, to explain similarities, and to establish broader historical patterns or identify alternatives. In so doing, historians attempt to avoid overspecialization; they seek to widen their horizons in order to facilitate generalization.

Yet, despite the many calls for historical comparison, there remains a gap between the great ambitions driving such scholarship and the resultant work product, a gap often exacerbated by a lack of conceptual reflection.

In general, comparative studies tend to focus on a select few variables and factors, to strive toward “macrocausal” explanations, to ask “why” instead of “how,” to establish limited contexts, and to seek the effective paradox.

Kate Hayes (holding mic), Manager, Aquatic (and Wetland) Ecosystem Restoration, Credit Valley Conservation outlines the current status of the Lakeview Waterfront Connection Project. Jaan Pill photo

It is precisely complexity, multicausal thinking, and broad contextualization which are for structural reasons not the strong points of historical comparisons. In other words, in a comparison, the very achievements of research in our respective fields are in danger of being lost. The problem of working with limited space, of potentially losing empirical ground, or overabstraction and oversimplification suggests that we refrain from an overall comparison of Nazi and Soviet violence and concentrate on case studies instead, however condensed they have to be. Given the described complexities, the model of totalitarianism provides no useful framework to us.

What the “structural reasons” may be, that make historical comparisons less than robust, with regard to “complexity, maulticausal thinking, and broad generalizations,” are not clear to this reader. Possibly, through further reading, I may gain an understanding of what the reasons are.

Military history mural at front of Small Arms Inspection Building, which was designated as a heritage site under the Ontario Heritage Act in 2009, as a result of a community initiative led by Jim Tovey who served as Ward 1 Councillor in Mississauga. The temporary wall at the left of the photo, protecting the site of the Hanlan Water Project, has subsequently been removed. Jaan Pill photo

Nor is it clear to me what the reference to “the problem of working with limited space, of potentially losing empirical ground, or over abstraction and oversimplification” means.

By way of guessing, I am assuming that perhaps the point is that overall comparisons of Nazi and Soviet mass murder are not the way to go, and that case studies – conducted, as the authors note, without reference to either totalitarianism or genocide as a conceptual framework – are the preferred option.

Nazi and Stalinist violence positioned as more than “state violence”

The authors note (p. 137) that

1940 fire hydrant located at Arsenal Lands east of Small Arms Inspection Building at Dixie Road and Lakeshore Road East in Mississauga. Jaan Pill photo

Given the extent of popular participation in the persecution of various victim groups – whether related to plunder, denunciation, professional advancement, or the use of forced labor – it does not seem useful to limit our analysis here to that of “state violence.”

The reference to popular participation in mass murder sets the scene for an elaboration (p. 137; again, I’ve added paragraph breaks and omitted footnote enumerations) of the chapter’s preferred conceptual framework:

Rather, we seek to understand Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union as extremely violent societies. They stand as the extreme cases within a group that includes not a few modern and colonial societies:

the late Ottoman Empire (1908-23),

a number of Eastern European countries within the Nazi-German sphere of influence,

Cambodia in the 1970s,

Indonesia since 1965,

Colombia throughout much of the twentieth century, and

the United States of America during the nineteenth century.

While the overall levels of violence may have been high in each case, they are in many respects dissimilar. Yet, in each case we can discern that rather than a solitary, uniform system of persecution and violence, a variety of policies and forms of mass violence were utilized against victim groups. Class-related civil war and, often, external conflict were intimately entwined with ethnic strife and selective social policies.

All of this prompts us to ask the question of social participation. Our focus here is on identifying policies enacted against common victim groups within both the German and Soviet systems and the often substantial differences in the type and intensity of the violence inflicted upon the groups in question. It is hoped that such an analysis will help us understand how both political systems and societies generated violence. [2]

Detail from In Situ event at Small Arms Inspection Building, Oct. 29, 2016. Lee-Enfield rifles were manufactured during the Second World War at the Small Arms Ltd. plant west of Etobicoke Creek in Mississauga. Jaan Pill photo

Distinction between mass violence and genocide

The term “genocide,” the authors note (p. 138) is without an “agreed-upon scholarly definition”:

As our analysis focuses upon groups that were subjected to varying types and levels of violence, “comparative genocide research” does not provide a useful conceptual framework. Nor, for that matter, would the creation of a typology or the application of a singular sociological, psychological, or political model appear promising as a starting point.

In most of the cases discussed here, the term “genocide” has rarely, if ever, been applied – whether this relates to the mass death of POWs, forced ethnic resettlement, or the persecution of “asocials.” Broadly speaking, a common, agreed-upon scholarly definition of “genocide” does not exist – and this arbitrariness is unsurprising, considering that “genocide ” is an inherently instrumental term, created and utilized for political purposes and oriented toward the unanimous moral condemnation, prevention if possible, military intervention, and juridical prosecution after a transition of power.

Moreover, the concept of “genocide” (for which intentions are central) implies that on a state level long-intended, carefully prepared master plans for destruction exist – a concept that appears too simple, though not entirely wrong, in light of recent research into the dynamics of state-organized mass violence.

Often, a comparison of “genocides” leads to endless debates about definitions, about the inclusion and exclusion of cases, and to a race for the more intentional, more original, or more total case. The understanding of “mass violence” applied here is more open and includes forced resettlement, deliberately inadequate supplies, sterilization, forced labor, and excessive imprisonment. [1]

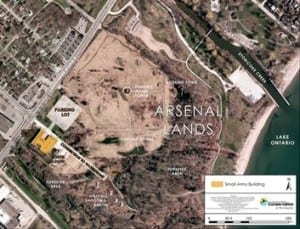

Aerial view of Arsenal Lands taken some time after the demolition of the Small Arms Ltd. munitions plant. The yellow building is the Small Arms Inspection Building. The parking lot that was in place just east of the Small Arms building has since been removed. Featured in a June 17, 2016 Mississauga News article, the photo is from the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority.

Mass murder of “so-called ‘asocials'”

A passage (p. 144) regarding this topic reads:

In 1948, 1949, and 1951, an array of secret [Soviet] governmental resolutions ordered the further intensification of police measures against beggars and vagrants, many of whom were war invalids.

A passage (p. 144) reads:

In Germany, too, a rather vaguely defined set of social subgroups was accused of deviant behavior and persecuted as “asocials.”

Some of the policies in this area date back to earlier times in Germany (p. 145):

Interestingly, pressure for more rigorous policies against the above-mentioned groups, including policies of internment sterilization, long preceded the Nazi assumption of power in 1933. The historical record amply demonstrates that welfare officials, medical doctors, and political parties had been discussing precisely such repressive policies and regulations well back into the nineteenth century; and, after the First World War, the German state actively began to extend its influence over labor markets by trading welfare provisions for increased control.

April 23, 2016: Volunteers prepare for several hours of clean-up in the Arsenal Lands where the Small Arms Inspection Building is located. On right is the south end of the building; on left is a woodlot, the site of a TRCA/Sawmill Sid portable sawmilling ash-tree salvaging project. Jaan Pill photo

Mass murder of victims of ethnic resettlement

The chapter’s comparative study of ethnic resettlement includes a passage (p. 157) concerning the development of Nazi extermination policies:

The ultimate realization that it would be impossible to deport certain population groups fully played a critical role in the development of Nazi extermination policies. For without deportation as a viable long-term option, the political pressure to make room for ethnic Germans in annexed western Poland soon led to ever more radical alternatives, including mass murder. When hospitals were needed for incoming ethnic Germans and for the German army between 1939 and 1941, for example, some 20,000 residents in homes for the disabled in the annexed Polish territories were simply killed. Also note that the first German extermination camp was located in Chelmno, Wartheland, and became operational on December 8, 1941; Auschwitz, located in incorporated eastern Upper Silesia, became an extermination camp in early 1942.

With regard to the Soviet-era ethnic cleansing of Chechens, the authors observe (pp. 159-60):

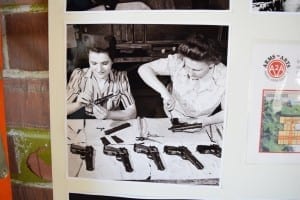

Detail from photo display at Sledgehammer Ceremony, April 6, 2015 at Small Arms Inspection Building. Jaan Pill photo

Note that several key features of this operation – “a hierarchy in the structure of command, a confined theater of operations, and a culture of impunity” – are common to other twentieth-century ethnic cleansings, as well.

Finally, over the course of six days in 1944 (February 23-8), 119,000 soldiers and officers of the NKVD arrested over 500,000 men, women, and children and forcibly removed them from their ancestral homelands. Deportees had an hour or so to gather their belongings (1oo kilograms per family) before being herded onto trucks and sealed in unheated freight cars. Because of poor weather conditions in the mountainous and isolated regions of Chechnya, a number of NKVD squads were temporarily stranded with their victims; thousands were outright massacred.

A press conference was held at the Small Arms Inspection Building on July 30, 2015 to announce that the Canadian government has approved up to $1 million for restoration of the historic facility. Linda Wigley, a former bullet loader, in one of the buildings where she worked throughout the Second World War. Staff photo by Rob Beintema. Source: July 30, 2015 Mississauga News article

After a three- to four-week journey, during the course of which many died from hunger and exhaustion, the deportees arrived in Kazakhstan or Central Asia and were dispatched to kolkhozes and factories. Uprooted from their homes, they not only suffered from appalling living conditions, but faced enormous difficulties in adapting to a totally new, and generally very hard, social and working environment.

Following this deportation, the Chechen-Ingush ASSR was suppressed from the collective memory, as well: its place-names were changed, its buildings destroyed, its cemeteries bulldozed, and Chechen national figures were removed from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia. In October 1948, a report of the Administration for Special Resettlements calculated that of the people deported from the Caucasus and Crimea in 1943 and 1944, nearly one in four, or 200,000, had died by mid-1948.

A view of the fence at the south side of the Small Arms Inspection Building, separating the lawn of the property from the parking lot. The photo evokes a sense of the atmosphere at the Small Arms Inspection Building in the 1940s. Jaan Pill photo

Mass murder of prisoners of war during and after Second World War

Gerlach and Werth note (p. 171) that

The main difference in the two cases, vis-a-vis the treatment of POWs, lies in the role played by political and military leaders. Only in the German case were there a high-level intention to kill large numbers of Soviet POWs and a program to realize it.

At the level of policy, Soviet authorities more often sought to improve the camp system and to ameliorate prisoners’ living conditions through organizational change and the punishment of Soviet soldiers who had violated their duties. Orders prohibiting abuse, which existed on the German side as well, seem to have been more frequent on the Soviet side.

Let us also not forget that hunger for Soviet and German POWs had a different significance than hunger in Germany. The starvation of prisoners in German hands served to maintain comfortable levels of food consumption for Germans, whereas in the Soviet Union, as a result of the German invasion and occupation of large swaths of territory, food was scarce for both civilians and the military, a situation that shifted to famine in 1942 and 1946.

Concluding remarks, regarding comparative study of mass murder

The chapter notes (p. 171) in an introduction to concluding remarks, that

Given the complexity of each individual case, it is difficult to draw overall conclusions or make generalizations about a subset of mass crimes, let alone about all of them together. We shall, therefore, confine ourselves to making a few key observations, rather than attempting to provide a general comparative explanatory framework for German and Soviet violence.

Small Arms Inspection Building. The site now evokes a sense of visual order and attractiveness, whereas over a previous span of many years it had evinced a sense of dereliction. Jaan Pill photo

As well (p. 172):

Mass violence is not simply a matter of police or other repressive state organs. From the victim group case studies presented here (“asocials,” victims of ethnic resettlement projects, and prisoners of war), it would seem that “initiative from below” and public participation or support were important factors in the genesis of such violence.

However, other factors were involved, as well, such as what could be called a given polity’s “overall acclimation to violence,” a factor related to that polity’s recent experiences of war, revolution, and counterrevolution. In both cases, we selected relatively understudied and underrecognized victim groups, groups that have been shown little remorse by German or Soviet society, let alone by their erstwhile perpetrators.

We selected groups that have not stood in the limelight of intense historical interest. This subject choice is also reflected in the relatively deficient state of research about them. These groups remain marginal to, if they are at all reflected in, the collective memory of the war, and they receive little empathy from the public or professional historians. More such groups could have been discussed, such as the more than 5 million civilians forced to work in Nazi Germany and the several hundred thousand foreign workers brought into the Soviet Union.

A major conclusion (p. 172) is that mass violence, in the categories chosen for study, did not occur in secrecy:

To begin with, this analysis questions the assertion that secrecy hid mass violence from the broader public – a finding corroborated by recent research on the Holocaust and on political oppression in both countries.

Additional conclusions (p. 172) can be summarized:

“participation in violence and mass murder was much broader than previously thought”

“victim groups often remained in close contact with the native population”

“there was an internal debate regarding such [violence and mass murder] policies”

“there were many who profited from repression and violence”

“there were many different arguments used to demand violence against the above-mentioned groups … every argument … was couched in language that aroused genuine public fears and concerns”

Additional highlights from the chapter’s conclusion

In both systems, there was at least a partial attempt to shield the broader population from knowledge about mass killings. (p. 173)

In the strategic use of the most intense forms of persecution and violence, however, the two regimes greatly differed. In Nazi Germany, for example, “asocials” were heavily persecuted domestically, but the number of camp arrests and related deaths never approached the magnitude attained in the Soviet Union. The same is true for the regime’s political opponents. Despite the brutal discipline of and the very real violence inflicted by the Nazi regime, their domestic approach was less confrontational and more integrative than the Soviet one. If one includes “asocials,” criminals, political opponents, Jews, Gypsies, the “terminally ill,” and, toward the end of the war, deserters, then the Nazi regime killed some 500,00 to 600,000 of its own citizens (0.6 to 0.8 percent of the total population). Yet, in areas occupied by the German army, exclusion rather than inclusion applied. Especially in Eastern Europe, German violence was extreme. Roughly speaking, some 12 to 14 million noncombatants were killed in occupied Europe during the war (5 to 6 percent of those under German occupation). The largest groups to suffer were European Jews, Soviet POWs, peasants caught up in antipartisan operations in Eastern and Southern Europe, and forced laborers deported to Germany. The nature of these categories underscores the fact that 96 percent of all victims of Nazi violence were non-German. (p. 175)

Former workers at Second World War Small Arms Ltd. munitions plant are acknowledged at Official Opening of Small Arms Inspection Building, June 23, 2018. Jaan Pill photo

German and Soviet violence differed in another fundamental way, as well: in all of the cases referenced above, as well as in many others, plans existed in Germany – plans that were often widely distributed and shared – for a scale of violence that far exceeded anything that actually transpired. While some 50,000 “asocials” may have been killed in Nazi Germany, experts estimated that 1.0 to 1.6 million “asocials” would ultimately need to be eliminated. Similarly, while more than 1 million people were resettled in the early stages of germanizing Eastern Europe and other German-annexed territories, plans required that at least 30 million more be resettled. Again: 3 million Soviet POWs died in German captivity, but there were plans to allow tens of millions of Soviet citizens, including POWs, to starve to death within a year following the German attack on the USSR. And, these are not the only cases: 11 million Jews were targeted for death in the Holocaust (6 million were killed); millions of additional foreign workers would have been deported to Germany, if conditions allowed; and, utopian military plans would only have spread the violence further. The planned magnitude of absolute violence – beyond the dimension of violence and death actually inflicted upon Europe – made Nazi Germany a unique threat. (p. 176)

The term “genocide” is not about to be dropped from usage

The current post underlines that the comparative study of Nazi and Stalinist mass murder requires a strong conceptual framework. Otherwise, you are spinning your wheels and wasting time.

An earlier post (originally posted on July 8, 2015) is concerned with a study entitled Extremely Violent Societies: Mass Violence in the Twentieth Century (2010) by Christian Gerlach. In chapter four of Beyond Totalitarianism (2009), Gerlach and co-author Nicolas Werth argue that the term “extremely violent societies” serves as a useful conceptual framework whereas the term “genocide” does not.

The term “genocide” is firmly established and is not about to be dropped from usage. For my own study of history – I refer to my reading of history, and of ongoing news reports – nonetheless, the alternative concept of “extremely violent societies” serves as a valuable conceptual framework, which enables me to make sense of things, about how the world works, which otherwise would be beyond my grasp.

An Aug. 17, 2021 New York Times article is entitled: “The Morally Troubling ‘Dirty Work’ We Pay Others to Do in Our Place.”

An excerpt reads:

As for drone warriors, toward whom the most vitriolic disapprobation has often been directed, Press reminds us that joining the military is often a way to escape poverty and the many traps it entails. Within the military, cyberwarfare is often considered dishonorable compared with in-person operations, because the dangers are not at all commensurate with the capacity to harm. But Press reports that some of those working in secretive drone warfare programs were offered little explanation of what they would be doing, and as they came to comprehend their missions they spiraled psychologically, from disappointment to disgust or suicidal despair.

In Press’s moral worldview, there are not only guilt and innocence, but rather fine-grained degrees of culpability and exculpation that fit uneasily with the sensibilities of a sound-bite-driven social media culture. Many of the workers he encountered blamed themselves for the harms they had done. They were victims of “moral injury,” meaning they had violated their own core values and were suffering profoundly for it. Press often reveals this suffering in descriptions of physical symptoms; Harriet, a prison psychologist, finds that her hair is falling out in clumps.

This section of the book, on the incarceration of the mentally ill, is the most disturbing, powerfully evoking our hypocrisy as a society. Harriet’s anguish is juxtaposed on the one hand with the terrifying plight of her incarcerated patients and on the other with the psychopathic cruelty of the guards responsible for them. Since the closure of many state psychiatric hospitals beginning in the 1970s, mentally ill people have often been held in prisons. Their psychological torment is not incomprehensible to educated Americans: Our literary culture is powerfully rooted in experiences of depression, mania and psychosis — conditions taken to have quasi-religious significance in the work of Emily Dickinson, Robert Lowell, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Sylvia Plath and others.

A March 11, 2022 New York Times article is entitled, “Putin is ‘Profoundly Anti-Modern.” Masha Gessen explains what that means for the world.”

I do not subscribe to the New York Times. Instead I access through the Toronto Public Library website.

An excerpt from the transcript available at the above-noted link reads:

MASHA GESSEN: That’s a simple question and it has a simple answer. Yes. And we’ve never seen that more clearly than in the last couple of weeks. What has emerged is not only that Putin is unilaterally making decisions but that those decisions are based — you know, those enormous decisions, the decision to wage a war, are based on a series of conjectures and fantasies that he seems to have created out of whole cloth.

I think it’s a combination of two things. One is actual physical and mental isolation, which apparently has been exacerbated by Covid. He had an extremely tiny circle of interlocutors before the pandemic. And he has apparently cut it down to something like zero since the pandemic began. So we’re — I mean, we’re living in a world — a world — not just a country, but a world that is right now being shaped by a man who has been thinking alone, and not very well, but also, most dangerously alone for two years.

In a further excerpt, Masha Gessen notes:

But Putin appears to be placing himself on a continuum of Russian history that he sees as a series of great leaders beginning with Ivan the Terrible. Ivan the Terrible was not an emperor that Russians particularly revered ever before Vladimir Putin’s reign. But the first monument to Ivan the Terrible went up, I guess, six or seven years ago in Russia. So Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, Joseph Stalin, and Vladimir Putin. It’s a huge span. It’s a series of great, brutal, expansionist dictators.

He skips right over the great divide of the October Revolution. He doesn’t see the Soviet period as distinct in Russian history. And so he gave a scary and rambling and ridiculous speech on February 21 by way of introducing this new invasion of Ukraine. But as a Putin text, it was quite remarkable because he laid out his vision of the entire Soviet period in more detail than he ever has before.

And what he said was that — without using the word empire — but he said that that whole Soviet way of constituting the empire by nominally giving its constituent parts the rights of statehood and nominally making the union voluntary was a fiction. That, in fact, there is a continuous history from the Russian Empire to the present day and that all the separations from Moscow’s rule that have occurred over the period of the last 100-plus years are illegitimate.

Note 1

The discussion brings to mind a post entitled:

Control: The Dark History and Troubling Present of Eugenics (2023) is among many books I’ve read about the topic

Note 2

Caroline Elkins presents an overview that would lead an observer to possibly conclude that the British empire can be justifiably included in a list of instances of ‘extremely violent societies’; with regard to her work an Oct. 18, 2022 post is entitled:

Caroline Elkins (2022) outlines the legacy of violence of the British empire

ALSO BY CAROLINE ELKINS

Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya (2005)

Settler Colonialism in the Twentieth Century: Projects, Practices, Legacies (2005)

Time for Reparations: A Global Perspective (2021)

A blurb for the latter study reads:

In this sweeping international perspective on reparations, Time for Reparations makes the case that past state injustice – be it slavery or colonization, forced sterilization or widespread atrocities – has enduring consequences that generate ongoing harm, which needs to be addressed as a matter of justice and equity.

Time for Reparations provides a wealth of detailed and diverse examples of state injustice, from enslavement of African Americans in the United States and Roma in Romania to colonial exploitation and brutality in Guatemala, Algeria, Indonesia, Jamaica, and Guadeloupe. From many vantage points, contributing authors discuss different reparative strategies and the impact they would have on the lives of survivor or descent communities.

One of the strengths of this book is its interdisciplinary perspective – contributors are historians, anthropologists, human rights lawyers, sociologists, and political scientists. Many of the authors are both scholars and advocates, actively involved in one capacity or another in the struggles for reparations they describe. The book therefore has a broad and inclusive scope, aided by an accessible and cogent writing style. It appeals to scholars, students, advocates and others concerned about addressing some of the most profound and enduring injustices of our time.

An excerpt from Legacy of Violence (2022) – Chapter 2, “Wars Small and Great” reads:

I wrote this book because my previous work, Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya, raised unanswered questions about violence in the British Empire. It documented the systematic violence that took place in Kenya’s detention camps during the Mau Mau Emergency (1952-60). Imperial Reckoning ‘s research was arduous because countless documents were missing from the official archives in London and Nairobi. I spent years sifting through remaining fragments of evidence and also amassed other historical sources from private document collections, newspaper archives, and hundreds of interviews that I undertook with former colonial officials and survivors of the detention system. During the course of this research, I recognized that for many British officials and security force members Kenya was not their first colonial war, and for others it would not be their last. Some suggested that Kenya’s settler community and its virulent racism rendered the colony unique. But perhaps Kenya wasn’t so exceptional? I felt I had stepped into a historical moment that was part of a bigger connective story about imperial violence after the Second World War that began in Palestine and moved to Malaya, Kenya, Cyprus, and Aden. It was this story that I set out to investigate over a decade ago.

A second excerpt reads:

By the fall of 1900, the British, under Roberts’s command, had taken nominal control of the Boer Republic. Now the war moved into its final phase as Afrikaners adopted a highly effective guerrilla strategy. To close the war, Kitchener took full charge of the army as commander in chief and launched an all-out assault on an entire ethnic population: or as Kipling termed it, a “dress parade for Armageddon.”[21] The British Army introduced a new blockhouse strategy that, combined with barbed-wire fences, divided the massive interior into smaller areas. Kitchener then deployed a scorched earth policy and systematically burned crops and dumped salt to prevent future cultivation. Sweeper columns mopped up any residual Afrikaner forces. Kitchener eventually deported thirty thousand prisoners of war to remote comers of the empire.[22] British troops also razed homesteads, poisoned wells, and corralled into concentration camps Afrikaner women and children as well as African laborers.

Kitchener was drawing on imperial precedents: this was not the first time the British Empire had sought to solve a crisis through mass encampment. Since 1857 officials in India had experimented with a series of confinement measures that were as much about reform as they were about security and punishment. The Indian Mutiny had spawned the mass incarceration of twenty thousand rebellious subjects whom British officials exiled to the Andaman Islands. There, sparse tented conditions and forced labor were to impart a sense of Victorian-era rehabilitation. Indeed, temporarily separating “degenerate” and “dangerous” segments of the population from the body politic was a hallmark of nineteenth century Britain. The Poor Law of 1834 and the Habitual Criminals Act of 1869 created social categories of Britons who, like the empire’s subjects, were part of liberalism’s underbelly. It wasn’t just a matter of incarcerating these threats to society; it was also to be an exercise in reforming them through hard physical labor, thus rendering them more rational and civilized. The Raj imported these ideas through legal mechanisms – it translated Britain’s Habitual Criminals Act into India’s Criminal Tribes Act – as well as through camp systems that reflected the metaphorical language of contagion.

A third excerpt reads:

Concepts about mass confinement and reform of refugees in India, along with Victorian-inspired ideals regarding rations and labor, traveled to South Africa during the war. With Kitchener’s scorched earth tactics, however, the so-called refugee sites swelled with civilians. Noncombatants comprised the crucial passive wing that offered supplies and informal intelligence to the commandos, and Kitchener was determined to control the Afrikaner and Black “undesirable” populations and, with it, deny the guerrillas their much-needed supply lines. Yet the commander in chief’s tactics went beyond dismantling guerrilla resources. He designed concentration camps, about one hundred in all, as punitive hostage sites. Women and children of active guerrillas endured harsher treatment with smaller rations as Kitchener sought to “work on the feelings of the men.” Moreover, he targeted the Afrikaner women who were “more bitter than the men”; according to him, the one way to “bring them to their senses” was to weaken them in the camps.[25] The war transformed these women and their children into “legitimate targets of violence,” as the historian Aidan Forth suggestsJ26] As far as Milner and Kitchener were concerned, the Afrikaners in the camps were “verminous,” no doubt emaciated from meager rations and poor sanitation’s effects. Kitchener’s forces had to either capture the “infested” Afrikaner population or kill them.[27]

British forces herded into the camps more than one hundred thousand Afrikaners who died at alarming rates. Malnutrition, starvation, and outbreaks of endemic diseases wiped out approximately thirty thousand, the disproportionate number of whom were children.[28] Whether the civilian deaths were a deliberate or an unintended consequence of Kitchener’s war plans, the establishment of the British concentration camps in South Africa represented the first time a single ethnic group had been targeted en masse for detention or deportation. Reports of camp conditions and death tolls began filtering to Britain in the spring of 1901. The public’s response ranged from indifference to outrage.

Kitchener, Ontario

A June 16, 2020 CTV article is entitled: “‘We cannot erase history’: Where Kitchener and its councillors stand on renaming the city.”

An excerpt reads:

“It’s not surprising that recent world events have us contemplating the origins of our City’s name,” city officials said in a statement to CTV News Kitchener. “We acknowledge that the legacy of our namesake, Horatio Herbert Kitchener, a decorated British Earl who established concentration camps during the Boer War, is not one to be celebrated.”

A June 9, 2023 Inside Story article is entitled: “Crimea’s Tatars and Russia’s war: The fate of a displaced people lies at the heart of the war in Ukraine — and how it might be resolved.”

An excerpt reads:

A more likely explanation for the Soviet move is that the paranoid Stalin wanted to clear his country’s borderlands of Turkic or Islamic peoples in advance of a possible war with Turkey (which never happened). The Crimean Tatars were one of many peoples from the country’s periphery considered suspect and transported en masse to Central Asia or Siberia: others included Chechens, Ingush, Kalmyks, Meskhetian Turks, Balkars and Karachai, as well as ethnic Koreans, Volga Germans and Finns.

The Crimean Tatars’ forced exile was but the latest chapter in a poorly known story that is as bleak and tragic as those experienced by many indigenous peoples following conquest and colonisation. It has rightly been described as genocide, not least by the Russian parliament in the heady, democratic days of 1991. The Tartars’ tale forms a crucial backdrop to understanding the current war in Ukraine, and its possible resolution.

A Jan. 31, 2024 New York Times article is entitled: “Rescuing the Holocaust From Distortion and Cliché: A new book by the historian Dan Stone seeks to amend – and expand – our understanding of the genocide.”

An excerpt reads:

Stone resists thinking in terms of lessons, though he believes that the history of the Holocaust offers a warning. It has little to do with anything so nebulous and ubiquitous as “intolerance,” or even “hatred,” he says, and more to do with politics and the state. After all, the Nazis were ushered into German government by conservative elites cynically intent on clinging to power. Today, Stone writes, eyeing the insurgent rise of the radical right in Europe and elsewhere, “fascism is not yet in power. But it is knocking on the door.”