Michael Mizzi, a senior planning manager at City of Toronto, spoke about “missing middle” at Nov. 18, 2020 Long Branch Neighbourhood Association AGM

Updates

A Dec. 16, 2020 Treehugger article is entitled: “This Modern Tiny House Rental Brings in Extra Income for Retiree. Built in an older woman’s backyard, this modern tiny house rental brings in extra cash to help pay the bills.”

An excerpt (the embedded links have been omitted) reads:

That’s the case with this lovely tiny house in Atlanta, Georgia, one of two which were commissioned and constructed by tiny house builder TruForm Tiny (previously) in the backyard of a retiree. Brandi, who is the woman’s daughter, helps to manage the two tiny houses under the banner of FieldTrip ATL. She tells us: “We built these to support my elderly mom who lives in the main house.”

The Canadian Urban Institute website features a related article: What is the Missing Middle? A Toronto Housing Challenge Demystified.”

A Sept. 5, 2019 Canadian Architect article is entitled: “Editorial: Finding the Missing Middle.”

*

By Jaan Pill, Preserved Stories

At the Nov. 18, 2020 virtual AGM of the Long Branch Neighbourhood Association, Michael Mizzi, a senior planning manager at the City of Toronto, spoke about a plan to “gently’” increase housing density across the city.

A local resident, David Godley, had introduced Michael Mizzi, who lives in South Etobicoke, to the Long Branch Neighbourhood Association. In a Q & A after his talk, Mizzi noted that Ward 3 (Etobicoke-Lakeshore) has the highest number of applications at the Committee of Adjustment, of any ward in the city.

Mizzi, director of zoning and secretary-treasurer of the Committee of Adjustment, also said with regard to Long Branch that, “I think it’s considered one of the more developable areas of the city, one of the more desirable areas by builders, so managing that growth, it will be a challenge for organizations like yourself and the planning department.”

Directions from Council

Toronto Council has announced ways to address the city’s urgent need for additional housing.

Toronto’s housing challenges include shrinking family sizes giving rise to underused houses. Years ago, many neighbourhoods housed many more people than they do now. As well, many residents now want to age in place in communities where they’ve lived for many years, while recent arrivals to the city, whose numbers are increasing, also need a place to live.

Michael Mizzi noted that Toronto has begun to expand laneway housing and secondary suites, thereby adding extra units in neighbourhoods, “without significant impacts.”

The next steps are directed toward an increase in gentle density across the city. The proposed new measures focus on the building of a “missing middle” form of housing, which, as a Council motion notes, ranges “from duplexes to low-rise walk-up apartments.” The construction would take place in areas designated as Neighbourhoods, which in the city’s Official Plan is called the Yellowbelt.

Slide 1 – Directions from Council

Mizzi’s first slide outlined directions from Toronto Council. As part of a housing initiative, the chief planner has been directed to report on options and a timeline to increase housing in a missing middle category, and to consult with registered community associations before reporting back to Council.

The planning division has been asked to report on possible options and planning permissions, which would allow for a gentle increase in density across the city. As well, Council has called for a design competition, which, in Mizzi’s words, “could help shape policies for a more permissive zoning regime” for Toronto. A work program is in place for the next 18 months. A series of expanded or changed zoning permissions are to be brought forward in about the next three years.

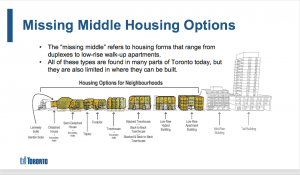

Slide 2 – Missing Middle

Mizzi noted that the term “missing middle” means different things in different jurisdictions:

“In Toronto’s context – because it’s different across cities in Ontario, and the country; people define it with some variation – for us, it’s not detached houses, and it’s not mid-rises: it’s everything in-between.

“So, that would be duplexes, multiplexes such as triplexes or fourplexes, walk-up four-storey apartments, and other hybrids, like townhouses.

“At the city, we also consider secondary suites, laneway suites, and other accessory dwelling units as part of this sort of continuum, between detached houses and mid-rises. So, they represent, for us, this form of gentle density that we want to expand, from the direction of Council, more widely across the city.”

“Now, it’s important that the title – it’s got a lot of press; it’s on Twitter quite a bit – the missing middle, these types aren’t missing in Toronto, but they’re relatively missing in new development.”

Mizzi noted that about 45 per cent of housing in Toronto is dwellings over five storeys tall. So, almost half of the city lives in apartments above five storeys, while 24 per cent live in detached houses, and 31 per cent live in the types in-between: the missing middle.

He added that Committee of Adjustment applications to build new houses in neighbourhoods – “notwithstanding what community associations see” – represent only a small proportion of applications. Most current proposals involve buildings over five storeys.

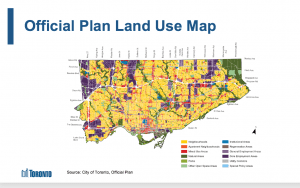

Slide 3 – Toronto’s Official Plan Map

On Toronto’s land use maps, the colour yellow represents the low scale neighbourhoods. This colour is spread out all across the map. However, appearances in this case are deceiving, because what you see on the map gives an exaggerated sense of the scope of the Yellowbelt.

“If you add up the land parcels,” Mizzi said, “only 35 per cent of the city is actually designated Neighbourhoods.” That said, the low scale neighbourhoods do indeed represent the most extensive land use in the city: “1.4 or 1.5 million, of 2.7 or 2.8 million people, live in the yellow area, according to the last census.”

What does the Official Plan say the city wants to do, in terms of where we direct housing? It says to focus on areas best served by transit and existing infrastructure. Those areas are designated for growth; a lot of such areas are described as “stable but not necessarily static.” The Neighbourhood designation permits lower scale buildings and, in a lot of cases, other types of uses like triplexes, townhouses, and walk-ups.

Development in neighbourhoods is also subject to development criteria; for example, it is required to “respect and reinforce” the existing physical character of each neighbourhood. The Yellowbelt is extensive; there’s considerable variation in its organization: in the layout of the streets, building forms, and demographics. It can, Mizzi said, be challenging to deal with developers and neighbourhood associations in these areas but there are “significant opportunities.”

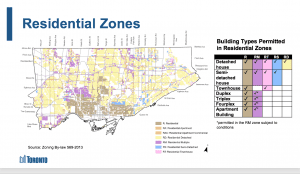

Slide 4 – Residential Zones

The map is based on Toronto’s Official Plan. Mizzi noted you can’t talk about the missing middle without talking about the zoning of neighbourhoods. The type of residential building that’s found in a given neighbourhood is what is permitted by way of local zoning, and the type of building helps to define the local character.

In the amalgamated city of Toronto, residential zoning is generally more permissive in the pre-World War Two neighbourhoods, primarily the former city of Toronto. You can see this in the brown tone on the map, where it’s zoned R-Residential. This is far more permissive. The little chart on Slide 4 shows what it permits: Detached house; semi-detached house; townhouse; duplex, triplex; fourplex; and apartment building.

Yet, if you go to the more modern or master-planned neighbourhoods – that is, the postwar, planned areas – of what were the suburbs at one time, such as Etobicoke, North York, and Scarborough, you have much more restrictive zoning. It’s primarily RD – Residential Detached.

A large part of the city – about 32 per cent of its land parcels – is zoned RD. If we leave out rights of way, about 70 per cent of the lands-designated neighbourhoods have zoning permissions that only allow for detached houses, “leaving many neighbourhoods in our opinion with very limited options.”

Secondary suites, recently added by the province and then by the city, are a relatively new as of right option to add to any detached house. Mizzi noted that the city’s zoning team has brought secondary suites right across the city.

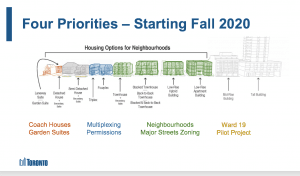

Slide 5 – Four Priorities, starting Fall 2020

Coach houses and garden suites. The planning team has asked Council to endorse four priority projects, to advance in the next year. On the slide, these are not presented in order of priority. First from the left are coach houses and garden suites. The objective is to develop Official Plan policy and zoning bylaw amendments to permit garden suites and coach houses across the city.

Some considerations include an evaluation, over the coming year, of an ongoing pilot on laneway suites, which are now permitted where lanes exist, which is primarily in the former city of Toronto.

The planning team will also look at development charges and parks levy credits and other fees that affect the building of other forms of housing. Mizzi said that “many people” say that things like development charges inhibit opportunity for missing middle housing. A preliminary report will outline where to go with coach houses and garden suites.

Multiplexing permissions. The second category involves adding units, such as duplexes and triplexes, to what’s already there within the building envelopes. Again, policy and zoning changes will be required, in order to accommodate more units within the existing housing stock. Analysis and consultation will start soon, across the city. A team has been created, which among other things will talk with neighbourhood associations.

Major streets. A third area involves 250 kilometres of major streets. The city has a classification called Avenues. These streets – an example is The Queensway – carry a lot of the new mid-rises in the city.

Toronto has a lot of major streets; they are defined and shown in the zoning bylaw. A lot of residential properties, at very low scale, front along major streets such as Islington or Kipling Avenue.

Many postwar bungalows on relatively good-sized lots are located on major arterials served by hundreds of buses on the way to subway stations. Most of these streets – such as Dufferin Street and Lawrence Avenue – have a low amount of housing on them, and yet there are large rights of way for the housing that does exist on them.

Mizzi spoke of a feeling that the major streets represent a major opportunity for the city to explore zoning changes especially given that they feature big rights of way.

Ward 19. At the request of Ward 19 (Beaches-East York) Councillor Brad Bradford, a pilot is looking at options to demonstrate these three other opportunities. The pilot will work with CreateTO, the city’s real estate agency, to test on some sites how the city might fit in some of these housing priorities, and how such a fitting in would drive the associated zoning changes.

This demonstration project will test for affordability and sustainable development; it will guide how to deal with regulatory and financial issues.

Mizzi spoke of four teams that were in the process of being confirmed, with roughly two co-leads and eight planning staff on each of them. About 40 people are involved altogether.

Q & A

The talk ended with a Q & A.

A question concerned details about a development at Lake Shore Blvd. West and Islington Avenue. Mizzi answered that the proposed priority housing areas are not focused on any specific projects in any neighbourhood right now. The effort here is general changes to Official Plan and zoning provisions to facilitate gentle density across the city.

Coach houses. A question concerned details related to coach houses, and a report that is coming out in January 2021. Mizzi noted that the January report will not bring forward recommendations in terms of zoning changes across the city, to permit coach houses. It’s a report, instead, to bring forward what planners are proposing to study, in greater detail, after which consultations will proceed. That project will occupy the planning teams all through the next year.

He added that coach houses, which are called different things in different cities, have moved forward in various ways in other municipalities such as Ottawa. The concept is similar to laneway housing. The buildings are subordinate to the main house on a property, and they are serviced off of such a main house. From a zoning point of view, they’re usually lower scale than a main building.

There will be issues that come up with lot sizes. Is the lot big enough to support the additional building? Is there an existing garage that can be converted? What if such a garage sits right on the lot line? Those challenges will concern some neighbourhoods “and so we’ll look closely at those kind of performance standards – the setbacks, the heights. That’s work still to be done in 2021.”

Next 20 years

Question: “From your opinion, what is Lake Shore and Long Branch primed for in the next 20 years? What types of changes should we expect out of more density, if any?”

Michael Mizzi: “I wish I was so knowledgeable on what was going to happen 20 years from now. You know, I can tell you something, for your audience. I used to be, actually, the planning manager for South Etobicoke for many years. Councillor Grimes was a councillor for the latter part of my tenure, when I was in South Etobicoke. And it’s actually, from a Committee of Adjustment point of view, our busiest ward in the entire city, of all 25 wards.

“Councillor Grimes’s ward [Ward 3, Etobicoke-Lakeshore] takes in the most applications, at the CofA. So, it’s clearly a really desirable area, and we know it’s because it’s got many generous lot neighbourhoods. So, a lot of lots in some of the neighbourhoods are very generous, well sited on the lake. It’s got the only streetcar line that’s going west to the edge of the city. Internally, we feel South Etobicoke will probably face development pressures that are greater than large parts of the rest of the city.

“You can see it happening right now in Humber Bay Shores. The cookie factory there: Mr. Christie; and certainly, your neighbourhood has felt enormous pressure in terms of lot severances. You actually have more lot severances occur in Long Branch and South Etobicoke than anywhere else in the city.

“I don’t see that pressure subsiding. I think it’s considered one of the more developable areas of the city, one of the more desirable areas by builders, so managing that growth, it will be a challenge for organizations like yourself and the planning department.”

Tree Canopy

Question: “You’ve kind of answered how do you see this project affecting Long Branch, but I guess that the piece along it, Michael, and I’ll add to your last question, is one of the reasons that Long Branch is so desirable is our tree canopy, and the feel of our neighbourhood.

“And the development pressure is, many people here feel, it’s taking that character away. So, what will the city do to protect the character, the existing character of Long Branch, which makes it desirable for us to live here, and how will this project affect us, where we already have a middle: we’re not missing the middle here in Long Branch.”

Michael Mizzi: “I’m well aware of, you know, the strong association of Long Branch with preservation of trees, and respect for the tree canopy, and growth of the tree canopy. I can tell you lots of neighbourhoods have that same desire and want to protect the tree canopy; and there’s always competing objectives with new development that affects, in particular, the private trees that are on lots that may be within the as of right, or the amended as of right, outline of new development, or new housing.

“And that challenge against the trees, and affecting roots, we’ve absolutely had street trees affected by new curb cuts, and wants for parking pads, and greater driveway and garage dimensions.

“It’s absolutely a challenge. We’re working closely with urban forestry, in fact at a lengthy meeting with urban forestry yesterday, on sort of the issue that I know is dear to your heart, which is getting the plans to show more information that come into the CofA, related to what’s on every property in terms of trees.

“It’s a big challenge; there is absolutely a conflict; there’s generally been a history, where if a building is permitted, or gets permitted by amendment, or by variance, that it often trumps, or impacts the tree that was there. It definitely has been the history. I think there’s a greater awareness and we’re, certainly, we’re educating, for example, the CofA panel members to be more cognizant of the impact of development on trees and the canopy.

“But I think it’s going to be an ongoing piece of work, education piece of work, and you guys do a great job with it, but it’s all over the city. I mean, it’s a big issue.”

Metrics

A last question (aside from additional written questions on Zoom) concerned metrics associated with progress on the missing middle.

In response, Michael Mizzi noted that the city has a “robust, strong business performance and standards group, plus a statistics team,” that’s constantly mining data.

“We do a lot of lot analyses at the city, and we have a pretty good handle on – you know, we can access every single parcel of land in the city, know what’s on those parcels of land; we have a good idea of the dimensions; we can dimension it all off.

“We are doing those analyses, and it is part of it; we know exactly how many detached units there are, or how many semis, and of course the metrics will be that we have more gentle forms of density occurring over the next coming years.

“For example, we’re monitoring now, how many building permit applications come in for secondary suites. We’ll be doing the same down the road, for multi-tenant housing, should that be approved.

“So, we constantly work with Toronto building at mining their building permit data, and it’s almost to the point now, where we can get it live every day up to date.

“So, we’ll be able to analyze the changes over time, I think fairly effectively in the coming years.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!