Deindustrialization has evoked diverse responses – as in Stratford, Ontario

Updates

1. An April 4, 2025 CNN article is entitled: “Trump’s self-inflicted tariff crisis sparks confusion, chaos and questions of competence.”

The article refers to an attempt by the current U.S. government to solve the problem of deindustrialization in America.

The article notes that what appear to be simple solutions to complex problems may on occasion indeed have traction at a political level. In practical terms, however, the enactment of such a category of solutions may give rise to questions about the competence of the officials who propose them. An excerpt reads:

Top officials insist that the tariffs are a first step towards building an economy that protects American workers and rebuilds manufacturing desecrated by the loss of US factory jobs to low wage economies in Asia and elsewhere.

As many commentators have noted, it’s questionable whether extreme tariffs will bring back the kinds of American factory jobs that were lost to deindustrialization many years ago.

2. An April 4, 2025 NBC article is entitled: “The White House is using tariffs to restore manufacturing. Data suggests it will take time.: Manufacturing jobs and infrastructure have shrunk since the 1970s, and it would take years to raise them back up.” An excerpt reads:

From cutting-edge software development to innovative financial products, knowledge economy work often offers better wages and working conditions than traditional manufacturing.

Hoffman, who grew up in Michigan and witnessed manufacturing’s 1970s heyday, said that while such factory jobs were good for “their time,” they were dirty, dangerous and physically demanding.

Today’s service economy, he said, creates different but superior opportunities: “It’s less wear and tear on the body, you’re able to work longer, you’re able to earn a good living.”

Thus we can say that a fact-driven policy, in any realm of governance, has a better chance of success than a conjecture-based policy.

3. An April 6, 2025 BBC article is entitled: “Trump has turned his back on the foundation of US economic might – the fallout will be messy.”

An excerpt reads:

For now, the US is checking out of the global trade system it created. It can continue without it. But the transition is going to be very messy indeed.

[End of updates]

*

Historian Steven High and photographer David Lewis have explored the impact of deindustrialization in North America. An overview of their work is available at the the Mason Historiographiki, a wiki (collaborative website) written and edited by graduate students in history at George Mason University:

In Corporate Wasteland, historian Steven High and photographer David W. Lewis present a unique investigation of the deindustrialized landscape that dots the Rust Belt across the United States. High and Lewis combine narratives from former industrial workers, with photographs of abandoned factories and interpretive essays to present a cohesive historical analysis of deindustrialization in North America. As they note in a new era of mobile capital, “In effect, people and places have become disposable.”(8) High and Lewis hope through oral history and photography to inject people back into the center of the field, and reassess their agency in light of common attitudes toward former factory workers and their moldering workplaces.

The photo below is from David Lewis’s website:

Deindustrialization in Ontario

Depending on one’s frame of reference, one can arrive at a wide range of overviews regarding deindustrialization in Ontario including an essay in the Literary Review of Canada. The latter essay, published in October 2010, remarks that:

No doubt, Ontario faces serious issues going forward. An aging population and the retirement of the baby boomers will put a massive strain on social services in the province, one already seen in ballooning healthcare costs. Health care threatens to derail another pressing need: the ongoing demand for skilled and educated workers continues to challenge Ontario, even as the province pours billions into apprenticeships and post-secondary education. Deindustrialization still threatens as China and India and many other countries continue to seek what the province now possesses, and to leapfrog places like Ontario. Similarly, the massive appetite for Ontario’s natural resources that is being fuelled by the Chinese manufacturing boom will lead to dramatic fluctuations and instability as the Chinese economy slows its breakneck growth.

This overview serves as a reminder that the job market in Canada has changed and continues to change.

Stratford, Ontario

Stratford has excelled in addressing the challenges of deindustrialization; it has been named as one of the Top Ten Intelligent Communities of 2011 [the link on which the following text is based is no longer active]:

Stratford, Ontario, Canada.

Since its founding as a mill town in the 1800s, Stratford has been a crossroads where agriculture, industry and culture meet. It has been the home to Canada’s largest furniture industry but also a railroad town and contributor to southern Ontario’s growth as a workshop of the automotive industry. Since 1952, it has also been home to the Stratford Shakespeare Festival, the largest employer in town and generates C$135m in local economic activity. Stratford, however, has had to take major steps to create a 21st Century economy. A city-owned company has laid 60 km of optical fiber and used it as the backbone of a public WiFi network. The University of Waterloo has opened a Stratford campus offering a Masters of Business Entrepreneurship and Technology program.

This has given rise to the Stratford Institute, a think tank focusing on digital media. Broadband and IT have also addressed the challenges of rural healthcare. Eighty percent of Stratford’s family physicians are on a broadband e-health portal for health records, administration and after-hours care, which has helped ease the region’s shortage of family practitioners.

Legacy of deindustrialization in Stratford

When I attended a workshop in Stratford, organized by the Heritage Conservation Centre, I visited the site of the University of Waterloo new media centre, which is located next to an immense railway workshop – a remarkable and imposing physical structure on what is known as the Cooper Site – that is now the subject of redevelopment discussions.

With regard to the UWO’s new media centre, an article at the above-noted link [which is no longer a live link] notes that:

The digital media campus is a founding hub of the new Canadian Digital Media Network. The University of Western Ontario also recently joined this pioneering digital media initiative by signing a memorandum of understanding with Waterloo and the city. The city is already a centre for many leading cultural and creative enterprises, including the Stratford festival, and so fits well with the creative entrepreneurial theme of the new institute.

With regard to redevelopment of a historic locomotive workshop in Stratford, an article at the above-noted link [which is no longer a live link] notes:

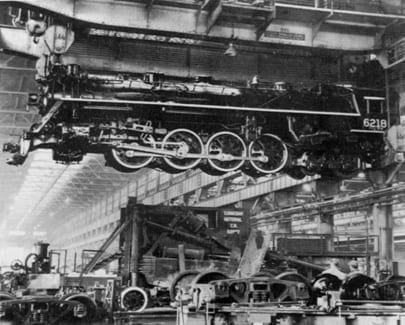

The locomotive workshop is enormous — 21 metres (70 feet) wide, 15.2 metres (50 feet) high and 240 metres (790 feet) long. There are two wings, each more than 150 metres (500 feet) long. In all, there is about 14,770-square-metres (159,000-square-feet) of space on the ground floor and 2,136-square-metres (23,000 square feet) on the second floor. The building covers about 11 of the site’s 17 acres. Stratford was a railway centre long before it became famous for its annual Shakespearean festival. The repair shops tended to Grand Trunk Railway locomotives from all over Eastern Canada. They employed more than 2,000 workers. The only other similar site in the country is in Winnipeg.

Image from an article related to redevelopment discussions regarding historic locomotive workshop in Stratford, Ontario [the link to the article is no longer active].

Consultant’s report

A consultant’s report [the link to the report is no longer active] on the Cooper Site in Stratford has concluded that the property has heritage value, and is worth either preserving or commemorating in some way.

Deindustrialization in Chicago

The story of deindustrialization brings to mind Chicago, a city which has shed its “blue-collar rustbelt image, and in its place it has joined the ranks of other global cities the world over” (Adrian Parr, 2013, p. 111).

In a chapter entitled Modern feeling and the green city in The Wrath of Capital (2013), Adrian Parr explores the role of the urban planning movement known as New Urbanism in the transformation of Chicago.

“New Urbanism,” she notes (pp. 116-117), “is the outcome of a marriage between the principles of environmentalism and neotraditional design and planning. It aspires to make cities and towns more user-friendly by creating walkable, efficient, and livable communities.”

“There is,” adds Parr, “enormous merit to the notion that a compact, well-planned community with a strong public infrastructure and green buildings is an effective way to reduce the ecological footprint of cities and metropolitan regions.

“Yet as critics of New Urbanism have pointed out, if we examine some of the movement’s touchstone examples – Seaside, Florida (the set for the film The Truman Show) and Celebration, Orlando (builty by Disney Co.) – we are presented with a more ominous world of white middle-class enclaves uniformly organized by a series of restrictions and regulations.”

Parr links deindustrialization and patholigization

According to Adrian Parr, deindustrialization in 1970s Chicago gave rise to urban crime, middle-class flight to the suburbs, and a growth in districts characterized by extreme poverty — and to what she describes as a “historical narrative that pathologizes Chicago’s poor urban African American communities” (p. 119).

She adds that “this patholigization reappeared In Mayor [Richard M.] Daley’s use of New Urbanism: demolishing public housing (‘the Projects’) and replacing it with mixed-income housing, restructuring public schools in low-income areas, and developing initiatives to address Chicago’s food deserts” (pp. 119-120).

Parr’s chapter on modern feeling and the green city provides a useful overview of what has worked well, and what has not worked well, with regard Chicago. The discussion brings to mind the earlier history of Regent Park in Toronto.

Chicago as a green city seeks to address climate change. With regard to this wider topic, Harald Welzer’s Climate Wars (2012) provides a cogent overview.

Raleigh bicycle brand

In a related discussion, a Feb. 8, 2013 Toronto Star article presents the rise and fall of the Raleigh bicycle brand as “a lesson in western deindustrialization.”

Updates

A July 18, 2013 CBC article reports that Detroit has recently filed for bankruptcy protection. A July 18, 2013 Globe and Mail article addresses the same topic, as does a July 18, 2013 New York Times report. A July 21, 2013 CBC article also highlights the topic.

Workers: An archaeology of the industrial age (1993) “serves as an elegy for the passing of traditional methods of labor and production,” in the words of a blurb at the Toronto Public Library.

A June 2, 2014 CBC article is entitled: “Detroit bankruptcy adviser: More U.S. cities to go bankrupt.”

An Oct. 23, 2014 article is entitled: “Stephen Poloz awaits sunrise after Canada’s long industrial sunset: Don Pittis.”

In the Introduction to Not Hollywood: Independent Film at the Twilight of the American Dream (2013), Sherry B. Ortner addresses deindustrialization and related topics.

A Dec. 15, 2014 Atlantic article is entitled: “The Mysterious Rise of the Non-Working Man.”

A Jan. 18, 2015 CBC article is entitled: “Iroquois Falls latest casualty of changing Northern Ontario economy: Town scrambles for ideas to replace lost jobs.”

An April 22, 2015 ThinkProgress article is entitled: “This Is What Poverty In Jamestown, Tennessee Looks Like.”

A May 4, 2015 CBC The Current article is entitled: “‘Second Machine Age’ author says machines are taking over humans.”

A March 16, 2016 CBC The Current article is entitled: “It’s not bigotry but bad trade deals driving Trump voters, says author Thomas Frank.”

A Sept. 4, 2019 London School of Education article is entitled: “Book Review: The Technology Trap: Capital, Labour and Power in the Age of Automation by Carl Benedikt Frey.”

An excerpt (I have omitted the embedded links within the excerpt) reads:

The key question, of which I am not sure the book offers a full explanation, is what accounts for this difference? Why are we now looking at a tendency towards labour-replacing technologies when we once had a proliferation of labour-enabling ones? There is mention of growing income and wealth disparities, yet the book lacks, perhaps, a fuller detailing of the political economy of inequality since the 1980s – there is very little mention of Margaret Thatcher and/or Ronald Reagan, strict anti-union legislation, corporate governance (or lack of) and declining rates of income and corporate taxation. These all seem relevant to a context in which workers risk not benefiting from an age of automation.

For a fuller explanation, we need to arguably travel beyond two outdated paradigms in which Frey’s work seems stuck. The first is what Isabelle Ferreras has called the ‘liberal economic theory of the firm’. This theory posits that free-market economics, and the institutions that uphold them, have propagated the idea that modern firms are organisations built to pursue a single goal – to generate return for capital investors. Ferreras maintains that such a position conveniently masks the fact that workers are equal partners in firms as they invest their time and labour in them, yet are hamstrung by the ‘despotic power’ of capital investors. This vast imbalance of power between capital and labour should therefore be positioned within the democratic deficit that exists in today’s world of work.

Frey also seems to fall into the trap of believing that any job is better than no job at all. The predominant danger of automation and artificial intelligence is framed as people falling out of the labour market entirely and there is little mention of the rise of poor quality or insecure jobs. While there is reference to jobs ‘where the productivity ceiling is low’ (237), the overriding sense is a binary that dichotomises employment as good and unemployment as bad. This overlooks a growing body of evidence that bad quality jobs can be worse for our health than unemployment as well as the increasing popular demand for shorting working weeks. It feels like a big omission since there is no discussion in the book of the emergent ‘post-work’ literature or, in the words of Andre Gorz, ‘working less so everyone can work’.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!