The Big Sleep (1946) demonstrates the effective application of screen direction, sound, lighting, and editing

The Big Sleep (1946) demonstrates four characteristic film techniques.

The techniques – applied in the opening credits and scenes of The Big Sleep (1946), based on a novel (1939) by Raymond Chandler – are:

(1) screen direction as described in Cinematic Storytelling (2005),

(2) Foley sound,

(3) film lighting, and

(4) sound and picture editing, as these items – that is, items 2, 3, and 4 – are discussed in The Filmmaker’s Handbook (2013).

Screen direction

Fig. 1. Laptop screen grab of silhouette scene from opening credits for The Big Sleep (1949). Left to right: Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall.

The credits open with the Warner Bros. logo followed by a silhouette (Fig. 1) achieved with backlighting of the lead characters, portrayed by Humphrey Bogart (as Philip Marlowe) and Lauren Bacall (as Vivian Rutledge, General Sternwood’s eldest daughter). The silhouette is recorded from a low camera angle. The flame of the lighter stands out in strong contrast, as the top third of the background is relatively dark.

Bogart lights Bacall’s cigarette.

The credits proceed in batches, left to right in the context of two-dimensional screen direction, accompanied by an optical effect simulating cigarettes smoke exhaled left to right across the screen.

The logo is introduced with stirring, aptly portentous music, which continues as the credits are screened.

Fig. 3. Screen grab – The Big Sleep (1946). Two cigarettes are in place in ashtray at bottom left of screen.

The camera moves in on an ashtray (visible at the bottom of Fig. 2) to create a diagonal movement, in terms of three-dimensional screen direction, from the middle ground of the Z-Axis to the foreground at screen left.

Ashtray emerges from the darkness

The ashtray, visible as a black object with pinpoints of reflected light, appears to emerge out of the darkness coming to rest at the bottom left of the screen.

The object is filmed from a high camera angle.

Bogart’s hand is seen to emerge out of the darkness to deftly and smoothly deposit his cigarette in the tray.

Bacall next deposits her cigarette, with equal care and attention to timing.

The two cigarettes, positioned vertically and approximately parallel, remain in view as the credits are presented (Fig. 3).

Sternwood mansion

The film then opens with a view of the front door of the Sternwood mansion (Fig. 4). The camera quickly pans diagonally to the lower left of the screen where a hand is seen to emerge from the left to press the buzzer located slightly to the left side of the screen (Fig. 5). The diagonal pan adds a sense of drama to the camera move.

From this point – in continuity with the screen direction established in the opening credits – the direction of movement is strongly and steadily from left to right.

We observe this sense of left to right movement as Bogart makes his way – briefly interrupted by his first encounter with the younger Sternwood daughters, Carmen (played by Martha Vickers) – to the greenhouse where the elderly General Sternwood (played by Charles Waldron) is waiting Bogart’s arrival.

Once Bogart has arrived for his meeting with Sternwood, we have the sense that the general is settled comfortably and securely – ensconced – at the end of a journey that has taken Bogart steadily and patiently from left to right in the space (mental space) in which we picture the movie to be taking place.

Foley sound

The footsteps of Bogart’s arrival at the door are clear yet unobtrusive. Enough Foley sound is evident to get across the point that a person is walking across the grounds of the property and then proceeds to walk inside the house. The sound of the footsteps does not, however, bring attention to itself.

Norris the Butler (Charles D. Brown), who meets Bogart at the door, has no Foley sound accompanying his steps in the scene in which he first meets Bogart.

One does not, however, notice the absence of the sound of footsteps. The viewer gets the sense that the butler just glides along, going about his work.

He only makes his presence felt as required, in the execution of his duties.

Lighting

Fig. 6. Screen grab – The Big Sleep (1946). Soft lighting is evident in this shot of Lauren Bacall. The key light is set fairly high. The forehead area gets less light than the face. The shadow from the nose is kept clear of the mouth and does not reach the smile line.

The lighting from each scene to the next is consistently low key, with a high contrast between light and dark areas.

Scenes are lit in pools of light existing in darkness, rather than being witness to even and uniform lighting.

Hard light, creating high contrast modelling of facial features, is used for close ups and medium shots featuring Bogart.

Soft light is used for close ups and medium shots of Bacall (Fig. 6) and the Sternwood sisters.

Such lighting is characteristic of black and white 1940s Hollywood movies in the film noir genre.

Editing

After Bogart has made some progress in his left to right movement across the imagined spatial setting of the film, the younger Sternwood sister, Carmen, pretends to lose her balance and ends up falling into his arms.

At the point (Fig. 7) where Bogart and the sister are aware that Norris the Butler has arrived on the scene, there’s a very quick dissolve, from the shot in which Bogart and the sister look to screen right, to the shot where Norris appears (Fig. 8).

The dissolve acts as a quick cut. It moves the story forward at a crisp and deliberate pace. No bit of information is belaboured in this film. Each point that needs to be made, is made quickly and effectively, and the story moves on.

Fig. 7. Screen grab – The Big Sleep (1946). Philip Marlowe and Carmen Sternwood notice that Norris the Butler is walking toward them.

Tobacco

The Big Sleep (1946) was first screened 68 years ago, as of 2014. When I see such 1940s films, I think about the fact that in the 1940s and 1950s and some ways beyond, people smoked everywhere and pretty much through all their waking hours – in schools, workplaces, homes, in cars with or without children present, and in movies. To an extent, times have changed. Possibly, sugar will, in time, undergo a similar change with regard to knowledge of health effects and social attitudes. It has been remarked that “Sugar is the new tobacco.”

Updates

We can add that sitting is also at times characterized at “the new smoking” – as in an August 2013 Runner’s World article, entitled: “Sitting is the new smoking – even for runners.” The subhead reads: “There’s no running away from it: The more you sit, the poorer your health and the earlier you may die, no matter how fit you are.”

A March 16, 2016 statnews.com article is entitled: “Despite your fancy standing desk, you’re still sitting too much.”

A March 21, 2016 Quartz article is entitled: “There’s not enough evidence to say standing desks are good for your health.”

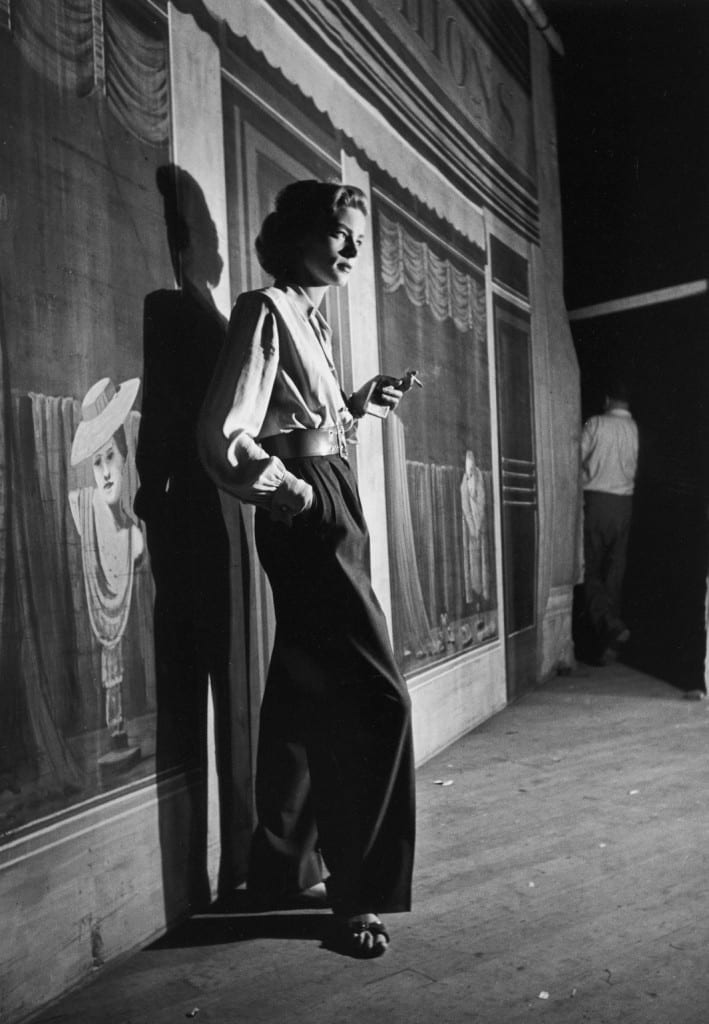

Portrait of Lauren Bacall by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1949. Source: April 10, 2014 Slate article entitled: “Defining cool, from Steve McQueen to Audrey Hepburn.”

As well, by way of an update, an April 10, 2014 Slate article, entitled “Defining cool, from Steve McQueen to Audrey Hepburn,” includes a 1949 Alfred Eisenstaedt portrait (above) of Lauren Bacall, photographed in the low key, high contrast lighting style reminiscent of (albeit not identical to) 1940s Hollywood black and white movies.

a Nov. 24, 2014 Guardian article is entitled: “The 100 best novels: No 62 – The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler (1939).”

A Dec. 28, 2014 New York Times Magazine article notes that “Lauren Bacall had the good fortune and the bad fortune to have been unforgettable early in life.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!