Ethnography as journalism

Ethnography, filmmaking, and sociolinguistics, among other pursuits, operate as variations of journalism. Such forms of journalism are especially relevant during the current crisis affecting journalism.

If I were offering advice to a young person interested in a career in journalism, I would advise them to explore the concept that many fields offer a person the opportunity to do what a journalist does.

Among those fields are ethnography and the practice of law. Some of the best journalism I’ve come across has been based upon ethnographic field research or has been published as widely-read legal reports by lawyers or judges who conduct inquiries, or render judgements, about a wide range of contentious issues.

A journalist requires a job or contract, and an audience. Print and online newspapers and magazines currently don’t offer many opportunities. For that reason, if you want to get paid to write, get a job as an anthropologist. Or a lawyer. There are many great jobs around where you get paid to write, and what you write sometimes makes a difference in people’s lives.

What is the distinction between an anthropologist and an ethnographer? What is the difference between ethnographic field research and the research that a journalist conducts? The differences are minor.

In order to make a living as a journalist posing as an anthropologist, you have to know who the person is who can get you published. That person is sometimes known as a publisher. In academic work, the person may not have the title of publisher but it’s not hard to figure out who that person is.

Producers, publishers, and curators are all terms for the same function. A good introduction to this topic can be found at my previous posts concerned with the production of independent films, such as:

Film work of Marjorie Harness Goodwin, linguistic anthropologist

As an anthropologist, you want to figure out who your audience is and what they are interested in. In other words, figure out the history of the discipline. A good resource is a chapter by Sherry B. Ortner in Culture/Power/History: A Reader in Contemporary Social Theory (1994).

The chapter is entitled: “Theory in Anthropology since the Sixties.” A key quotation (p. 382) reads:

The anthropology of the 1970s was much more obviously and transparently tied to real-world events than that of the preceding period. Starting in the late 1960s, in both the United States and France (less so in England), radical social movements emerged on a vast scale. First came the counterculture, then the antiwar movement, and then, just a bit later, the women’s movement: these movements not only affected the academic world, they originated in good part within it. Everything that was part of the existing order was questioned and criticized.

Was that written by an academic or a journalist? What’s the difference? Does it matter?

I much admire the film work of linguistic anthropologist Marjorie Harness Goodwin. The link in the previous sentence explains why.

In a previously noted link, I describe the high-quality scripts that Marjorie Harness Goodwin has created.

Among the scripts, or more precisely, transcripts, that she has created are descriptions about how bullying in school-based cliques, the subject of Goodwin’s linguistic anthropological research, actually occurs. Such a script gives a person a much better sense of what bullying, intimidation, and harassment entails than some general description based upon interviews and surveys.

Updates: Andy Warhol, sociologist

A Dec. 1, 2014 Slate article is entitled: “White House Will Fund Police Body Cameras, Review ‘Police Militarization’ Process.”

Update: A Dec. 1, 2014 CBC Radio interview about Andy Warhol and Ronald Reagan, positions Andy Warhol as an innovative sociologist (focusing on fame among other topics of interest), along with his roles as groundbreaking painter and photographer.

A Feb. 22, 2013 Phaidon article is entitled: “The fascinating story behind Andy Warhol’s soup cans.” The article notes:

With his Campbell’s Soup Cans installation at Ferus Gallery, the artist realised the possibility of creating works in series, and the visual effect of serial imagery. He continued making variations on his Soup Cans, stencilling multiple cans within a single canvas and so amplifying the effect of products stacked in a grocery store, an idea that he would later develop in the box sculptures. He also realised that the serial repetition of an image drained it of its meaning, an interesting phenomenon most poignantly presented in his Disasters, in which the constant exposure to their graphic displays of violence numbs the senses. And, perhaps the most significant outcome of this series was the artist’s push towards printing to achieve the mechanical appearance that he sought in his paintings.

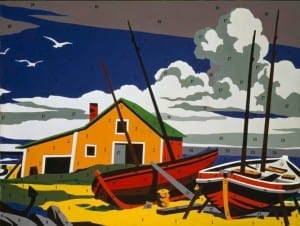

Do It Yourself (Seascape), 1962. Artist: Andy Warhol. Photograph: 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

The first sentence of a January/February 2015 Walrus Editor’s Note reads: “These are troubled times for North American journalism.”

An Oct. 28, 2015 CBC article is entitled: “Andy Warhol TIFF show explores artist’s obsession with stars, fame: Highlights include Warhol’s own memorabilia plus his videos, screen prints, photos.”

A Feb. 2, 2016 Ryerson Journalism Review article is entitled: ” ‘The greatest act of journalism ever’: Marie Wilson, of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, says journalism is an integral part of indigenous culture and history.”

A Feb. 2, 2016 Globe and Mail article is entitled: “Canada’s media: A crisis that cries out for a public inquiry.”

A Feb. 4, 2016 Toronto Star article is entitled: “From the eye of the hurricane, the ’crisis’ in journalism.”

A Jan. 7, 2016 CBC article is entitled: “The problem with newspapers today: the Marty Baron perspective: ‘Spotlight’s’ Marty Baron may be the last of the old-time Humphrey Bogart editors. Pity.”

A March 11, 2017 Toronto Star article is entitled: “Museums as newsrooms, university profs as journalists: A look at how museums could be a source of trusted civic information, as well as the roles of universities and ordinary people as newsrooms shrink.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!