Portugal’s low coronavirus caseload is attributed to a swift, flexible “worst-case scenario” response and early closure of schools and universities on March 16, 2020

As I’ve noted at previous posts some countries have excelled in responding to COVID-19.

An April 19, 2020 Guardian article is entitled: “Swift action kept Portugal’s coronavirus crisis in check, says minister: Country went into lockdown at earlier stage of epidemic than fellow European states.”

An excerpt reads:

That has not been the case in Portugal. “Political parties have adopted a responsible behaviour because everybody understood very well the importance of being united to tackle an unexpected pandemic with dramatic consequences,” said Sales.

According to Fronteira, the pandemic underscores the need for proper preparation. “That’s going to be crucial to the next stage of the epidemic as we start discussing whether to loosen the measures or not,” she said.

“It’s important to take one step at a time because you need to have time to measure the impact of each of the measures. For this type of response, you also need to have social and political cohesion to effectively implement public health measures.”

Sales said that while it was to soon to start drawing conclusions, “We are constantly learning with our outbreak and with other countries’ experiences. We will be better prepared for the next time, for sure.”

Portugal has moved quickly, Sweden has moved slowly

Portugal’s approach stands in contrast to a country such as Sweden, which has taken a more relaxed approach to the new coronavirus pandemic.

Click here for previous posts about Sweden >

An April 18, 2020 Guardian article is entitled: “Anger in Sweden as elderly pay price for coronavirus strategy: Staff with no masks or sanitiser fear for residents as hundreds die in care homes.”

An excerpt reads:

It was just a few days after the ban on visits to his mother’s nursing home in the Swedish city of Uppsala, on 3 April, that Magnus Bondesson started to get worried.

“They [the home] opened up for Skype calls and that’s when I saw two employees. I didn’t see any masks and they didn’t have gloves on,” says Bondesson, a start-up founder and app developer.

“When I called again a few days later I questioned the person helping out, asking why they didn’t use face masks, and he said they were just following the guidelines.”

That same week there were numerous reports in Sweden’s national news media about just how badly the country’s nursing homes were starting to be hit by the coronavirus, with hundreds of cases confirmed at homes in Stockholm, the worst affected region, and infections in homes across the country.

Since then pressure has mounted on the government to explain how, despite a stated aim of protecting the elderly from the risks of Covid-19, a third of fatalities have been people living in care homes.

Anecdotal observation regarding Swedish coronavirus response

My anecdotal observation, based on visits to Sweden over the past three-quarters of a century, is that the epidemiological resources operating at a governance level in Sweden in relation to COVID-19 have been less than optimal, for specified reasons.

The fact the resources have been less than optimal has not been evident to decision makers, however, despite the fact that many public health experts in Sweden have noted publicly that Sweden’s lax response to the coronavirus epidemic would have hugely tragic consequences.

Reinforcing the less than optimal decision making has been a characteristic deference to authority, articulated as a high level of trust in government among a large proportion of the Swedish population.

If I had to choose between trust and data I would go with data.

In some cases based on my anecdotal observation, Sweden depends upon a form of decision making where a single person is labelled the “designated expert” and that person’s views are unquestioned.

In such an approach, one person’s opinion can at times take precedence over the available data or evidence.

Such an approach stands in contrast to a more collegial one, in which views from many competent authorities are taken into account when decisions – particularly key decisions affecting governance – are made.

Portugal’s response has been and remains flexible because it’s strongly data-oriented. As the data changes, the response quickly changes accordingly. In contrast, an approach that depends more on opinion and less on data is more likely to be inflexible. Changing an opinion can be difficult. Changing a response as data changes can be done as a matter of course.

I’m aware of the downsides of generalizations such as mine about any topic. The comments I share are made with respect and with an awareness that there is much that is valuable and noteworthy in Sweden’s approach to life and to social organization.

Long term care is a concern worldwide

Over many decades I have visited people close to me when they were in hospital and long term care settings in Canada and Sweden. Being a source of support and connection for family members and friends in such circumstances is among the most valuable things a person can do in my judgement.

An April 17, 2020 Globe and Mail article is entitled: “We didn’t really see the epicentre of COVID-19, even after it was here.”

An excerpt reads:

For weeks, ordinary folks have been staying home. But personal support workers in Ontario were working a shift in one long-term care facility, getting residents out of bed or into a bath, then doing a shift at another one the next day. COVID-19 outbreaks infected not just residents but staff, who might bring it to another centre before showing symptoms.

Ontario officials worried that restricting staff to one workplace would leave shortages. But reorganizing workers to full-time needed to be done fast.

Hindsight is 20/20. Many things would have been done sooner if we had seen what was coming.

In this case, it was hard to see what was already here.

Public health workers are busy with things other than stats. But it is disconcerting if governments do not have up-to-date data.

An April 19, 2020 Toronto Star article is entitled: “Temporary agency workers have long been a crutch for a care system in crisis, experts say. Now, they are exempt from new COVID-19 health directives.”

An excerpt reads:

Even for directly-hired personal support workers, poor pay has long meant juggling multiple jobs at different homes, says Sharlene Stewart, president of Services Employees International Union Healthcare.

“Workers absolutely want one full-time job. But when you pay them so poorly … you have to work two jobs to barely make a living,” she said.

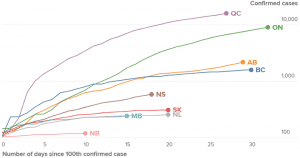

Source: April 17, 2020 Global News article entitled: “Canada is flattening the coronavirus curve. That’s ‘good news,’ expert explains.”

In Ontario as elsewhere, lack of testing continues to be a concern

I live in Ontario for which reason I find it of interest to follow news from this province.

Previous large cutbacks in public health spending is a concern with regard to Ontario as is the province’s low testing capability.

On the whole, Alberta and British Columbia appear to be doing a better job dealing with the pandemic than Ontario. The graph at the current post highlights current provincial trends in relation to “flattening the curve.”

It may be noted, and must be underlined, that compared to some other jurisdictions in the world, Ontario like other Canadian provinces is indeed among those flattening the curve. The one exception, as I understand from news reports on April 20, 2020 however, the curve is not yet flattening in Ontario long term care settings.

In all settings, as I understand, major challenges such as testing and contact tracing remain in Ontario as is the case in many other jurisdictions.

An April 17, 2020 Globe and Mail article is entitled: “Toronto Public Health struggling to keep up with contact tracing, doctors say.”

An excerpt reads:

Public health staff in Canada’s largest city are struggling to keep up with the vital work known as contact tracing, or alerting those associated with people who test positive for COVID-19 in a bid to curb its spread, some Toronto doctors say.

Doctors say that individuals who test positive can wait for days without a follow-up call from Toronto Public Health’s contact tracers, who perform the detective-like task of tracking a patient’s steps. In some cases, this means that friends or co-workers of a positive case are not being promptly instructed to self-isolate for the mandated 14 days.

Click here for previous posts about testing >

Lack of testing is an issue in many places, including Russia

A helpful overview of the need for testing is featured in an April 19, 2020 New York Times article entitled: “In Pandemic, a Remote Russian Region Orders a Lockdown – on Information: Trailing only Moscow in per capita infection, Komi faces a serious health crisis and wants to know who leaked the bad news.”

An excerpt reads:

With his region called out publicly by Russia’s health minister on Friday as one of several that had stumbled badly, Komi’s newly appointed governor, Vladimir Uyba, assured Mr. Putin during a teleconference that the rate of infection in his territory had slowed even as testing had increased.

But he acknowledged that even with three local laboratories now handling tests, meaning that samples no longer had to be sent to Novosibirsk in Siberia for analysis, less than 1 percent of residents had so far been tested. The governor pleaded with the president for help in establishing a modern infectious diseases center.

Mathematical models prepared by two Russian institutes predict that the outbreak will reach its peak in Komi early in May, leaving as many as 50,000 people infected, a 100-fold increase over the current number of confirmed cases.

Ernest Mazek, a Komi legal activist who has investigated the fiasco in Ezhva, said in a telephone interview that he did not think local officials were under any orders from Moscow to lie but simply feared telling the truth in a system that gives little incentive for honesty.

Click here for previous posts about Russia >

Ontario doctors’ association says help from government not enough

An April 19, 2020 Globe and Mail article is entitled: “Doctors’ association says help from government is not enough to survive COVID-19.”

An excerpt reads:

The Ontario government’s proposal for advance payments to doctors has not yet been finalized and still has to be negotiated with doctors, the OMA said.

Dr. Gandhi said the proposal also doesn’t address the issue that doctors will not be paid for virtual appointments for months because the government’s computer system isn’t ready to process new billing codes for the virtual screenings.

The provincial government has said the new billing codes have to be used so that the province receives valuable data about the use of online appointments, but the OMA has said a workaround is available.

However, the OMA says that a tracking code can be added to existing billing codes so that they can be paid sooner while the government still receives data.

The province has said the soonest that doctors will be paid for virtual appointments done now is in June.

“We’ve already seen clinics close,” said Dr. Gandhi, adding clinics need help sooner. “This is going to add a significant added backlog to our health care system in the coming months.”

Click here for previous posts about Ontario >

A quick response to COVID-19 entails avoidance of magical thinking

A capacity to see what was about to happen was key, in countries that have responded quickly to COVID-19. Of related interest: An April 20, 2020 STAT article is entitled: “The months of magical thinking: As the coronavirus swept over China, some experts were in denial.”

An excerpt reads:

The response to the coronavirus pandemic in the United States and other countries has been hobbled by a host of factors, many involving political and regulatory officials. Resistance to social distancing measures, testing debacles, and longtime failures to prepare for the possibility of a pandemic all played a role.

But a subtler, less-recognized factor contributed to the wasting of precious weeks in January and February, when preparations to try to stop the virus should have kicked immediately into high gear.

Magical thinking — you could call it denial — hampered the ability of even some of the most seasoned infectious diseases experts to recognize the full threat of what was bearing down on the world.

As China was seeking to rid itself of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, a number of leading infectious diseases scientists mused that the outbreak would be controlled or might burn itself out. Yes, there were cases outside China — just over 100 had been reported to the World Health Organization by Jan. 31 — but they were spread out in relatively small numbers in 19 countries. The virus, the thinking went, didn’t appear to be behaving as explosively outside of China as it had inside it.

In hindsight, that argument, from a biological point of view, didn’t make any sense — and it ignored a soon-to-be-apparent Epidemiology 101 lesson: It takes time for a virus that spreads from person to person to hit an exponential growth phase in transmission, even if every new case was infecting on average two to three other people.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!