On Sept. 2, 2021, we met for a high school picnic at an apartment parking lot with a great view of Lake Ontario. We learned how Bois-de-Saraguay in Montreal was saved from destruction.

View of Lake Ontario from parking lot near Cliff Lumsdon Park, South Etobicoke, Sept. 24, 2020. Jaan Pill photo

When we first began planning for our most recent Malcolm Campbell High School picnic which took place on Sept. 2, 2021, we were talking about meeting at Cliff Lumsdon Park in New Toronto, a neighbourhood in South Etobicoke.

Our previous meeting had been at Long Point Provincial Park on Lake Erie.

For the Sept. 2, 2021 picnic in Toronto, Bob Carswell let us know that after a week of really hot weather in late August, he would last no more than 10 seconds sitting in the hot sun at Cliff Lumsdon Park.

Bob suggested that we meet, instead, in the shade of the parking lot behind the low-rise apartment building where he lives, a short distance from the park. He could readily walk to the parking lot using a sturdy walker that he’s recently acquired, which works better than trying to walk using two canes.

A previous MCHS picnic took place at Cliff Lumsdon Park on Sept. 24, 2020. Left to right: Bob Carswell and Dan McPhail. Jaan Pill photo

We all agreed that the parking lot, with a great view of Lake Ontario and the Toronto skyline through a chainlink fence, would be a great place for us to meet. [1]

Low-rise apartment buildings with parking lots facing Lake Ontario

A pattern of land use decision making in the 1950s accounts for the many low-rise apartments that are now facing away from the lake in neighbourhoods such as Mimico, which is just east of New Toronto. Bob Carswell lives in such an apartment in New Toronto.

Left to right: Gina Cayer, Peter Reich, Jaan Pill, Scott Munro at Long Point Provincial Park on Lake Erie, July 22, 2021. Jaan Pill photo

Between 1950 and 1960, as a judicial inquiry (prompted by articles by Pierre Berton in the Toronto Daily Star) later determined, planning decisions at the Town of Mimico were made by builders rather than by city officials, with the result that zoning bylaws were ignored. That accounts for the way that apartments were built in Mimico in the 1950s.

Left to right: Dan McPhail, Jaan Pill, Bob Carswell at parking lot of apartment building where Bob Carswell lives, Sept. 2, 2021. Jaan Pill photo

I’ve been reading archival newspaper articles about Mimico at the Toronto Public Library website. Articles from the 1960s editions of the Globe and Mail are easy to locate and print out. The format the Toronto Star uses for the same era is more cumbersome but its archival articles are nonetheless also of much interest. [2]

Judge J. Ambrose Shea headed the Mimico judicial inquiry

A May 25, 2012 document entitled Mimico 20/20 Revitalization Cultural Heritage Resource Assessment, by URS Canada, explains how a dense collection of low-rise apartments came to be constructed along the east side of Lake Shore Blvd. West in the 1950s.

As I’ve outlined at a previous post, the Mimico 20/20 document notes (page 9) that:

Several options for administrative reorganization were considered in the years following the Second World War, eventually resulting in the amalgamation of Mimico and other Lake Shore communities into the Borough of Etobicoke in 1967.

During the same [postwar] period, most of the large waterfront estates in the study area were subdivided and sold off. The east side of Lake Shore Blvd was built up with a dense collection of anonymous low rise apartment buildings with their backs to the lake, and the shore itself – unbelievably – was given over to parking lots for the tenants. The reason for this is that from 1950-1960, building inspector Jack Book judged it better to encourage construction projects than to enforce zoning requirements. Book bowed to the wishes of the developers, presumably believing that in the long run, the tax base of the town would be stronger. The Judicial Inquiry, carried out by Judge Shea, concluded that:

It started with small by-law violations, sanctioned in the philosophy that Mimico needed building. From these small beginnings the builders, the real estate men and the developers took over. They took complete charge, and, if they were not encouraged, they were certainly not interfered with or impeded, to any appreciable extent, by members of council or officials.

Mr. Book spent time in prison [he received a two-month sentence] for perjury, and the developers’ spree was brought to a halt.

After 1962, the area remained relatively static in terms of development until the last two decades of the 20th century, when higher density condominium blocks began to encroach at the north end. The commercial street has undergone superficial modernization and remodeling without significant changes in scale or density.

The document refers to a Feb. 5, 1962 Toronto Daily Star article entitled: “Mimico Building Chief Rapped by Probe Judge.” You can access Judge Shea’s report at this link:

1 – Judge Shea Report – Feb 5 1962

To read it you would need to download the PDF and rotate the text.

A Dec. 15, 2011 article at the History of the Town of Mimico website, entitled “Mimico Building Scandal – Judicial Inquiry 1961,” describes the inquiry, which was held in 1961 at John English School.

An excerpt about the inquiry’s launch reads:

It began with a series of articles in the Toronto Star by Pierre Berton in May 1961. The first article was entitled “What’s Wrong in Mimico: The Strange Case of Mrs. Jackson”, which laid bare the obstacles that had been placed in the way of Mrs. Jackson obtaining a building permit so that she could sell her lakefront land which was now surrounded by apartment blocks on all sides.

View looking south toward Lake Ontario at Cliff Lumsdon Park: chunks of concrete and the like along the shoreline, June 16, 2021. Jaan Pill photo

Filling in the waters in Mimico, New Toronto, and Long Branch

The report by Judge J. Ambrose Shea refers to the practice of creating new parcels of land by filling in the waters along the waterfront.

A witness at the inquiry notes that, in Judge Shea’s words (p. 10), “for some time a problem has been created by the filling in of the waters along the lakefront, in connection with the continued apartment development and the demand for more and larger lakefront lands, resulting in conflict in municipal jurisdictions. The lakefront boundary of Mimico was the shore of the Lake as it was in January 1911 and included water lots that had been patented at that time.”

View looking east from Cliff Lumsdon Park, June 27, 2021. On the left can be seen higher density condominium blocks at the north end of Mimico. Jaan Pill photo

In New Toronto as in Mimico and Long Branch, you can see evidence – chunks of concrete and the like – of landfill projects of many years ago along the lakefront lands. [3]

Based on buildings in nearby neighbourhoods dating from the 1950s, it’s possible that decisions about land use, of the kind observed in Mimico, may also have been made elsewhere in those years such as in New Toronto. [4]

The Mimico inquiry gave rise to discussion in the 1960s about how evidence is dealt with in judicial inquiries as contrasted to criminal trials. [5]

Goodbye ol’ house

At our picnic, we talked about the house on Lavigne Street in Cartierville south of de Salaberry Street, where Dan McPhail lived after his family moved from Ahuntsic.

In the basement of the house, Dan came across writing on a wall which (by way of paraphrase) said, “Farewell ol’ house”, or maybe it said, “Goodbye ol’ house.” The exact wording we do not know.

Peter Parsons, a student at MCHS, may have written the message but that’s just an assumption. It may have been any of the three remaining occupants who wrote the message. Bob Carswell remarked that everyone, indeed, has lived in a house where in time someone would have said, “Goodbye ol’ house.”

Dan moved to the house around 1966 or ’67, “and the house was built in 1950, ’51, something like that, so it wasn’t really an ‘ol’ house’ at that time, you know.”

From my vantage point, I think of the choice of words as an expression of affection. A poignant sentence. I don’t remember things all that well. I have an episodic memory – I only remember certain things that are of significance, for whatever reason. From the time Dan first mentioned what was written at the house on Lavigne Street, I’ve remembered that ever since. It’s always stayed with me.

The house was sold after Mr. Parsons passed away leaving Mrs. Parsons and a son, Peter, and a daughter, Patricia. The family moved to an apartment on Dudemaine Street. Students at MCHS have shared recollections about Peter Parsons; his friends remember him fondly: Update regarding MCHS grad Peter Parsons.

Patricia was in my class in Morison School, as I recall. The last time I had the occasion to speak with her was when we happened to stop to talk on Lavigne Street (south of de Salaberry) one day, by which time I think she may have been studying at McGill.

As a child I knew little about Saraguay

On Sept. 2, 2021, we also talked about the history of Saraguay, concerning which Bob Carswell remarked:

It was a village, which consisted of estates, and then the village itself. And the people from the estates used to call the villagers Shack Town, because there was one street and the only farmhouse that was on the water was right down Alliance Avenue, and, so they used to call that street Shack Town, because all the wealthy people figured that a shack town, because it was full of shacks.

You know, the farmer or somebody put all sorts of little houses down there, and rented them out. And, of course, that started the Mic-Mac Restaurant up at the corner, which became the place where everybody from Shack Town used to come up the street, get their treats, and go back down.

The tennis court was put in by the rich. And they would come up in the early morning and play tennis, and then go across the street and get a drink or something from the Mic-Mac. So there’s a whole history to the whole area.

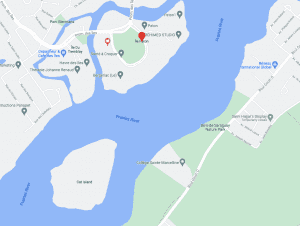

Paton’s Island and Cat Island on Rivière des Prairies between Laval and Montreal. Source: Google Maps

As a child I was familiar enough with Cartierville and Ville St-Laurent, but I did not spend much time in Saraguay. I now know Saraguay better than I did as a child, having heard many stories in recent years. I can, in fact, now point out Paton’s Island and Cat Island on a map that shows the Rivière des Prairies whereas previously their very existence did not register for me.

Paton’s Island is on the north side of the Back River across from the estates of Saraguay. The owner of the island was Hugh Paton; an excerpt from a description at househistree.com of Paton’s house on the island reads:

Le Paton

L’Abord-à-Plouffe, Quebec

Completed by 1886, for Hugh Paton (1852-1941) and his wife, Bella Robertson (d.1925), of Elmbank, Montreal. In 1880, Paton bought the island (then called Île Bourdeau) as a summer retreat for $2,800 from Arthur Bourdeau whose family had farmed it for several generations. He set about landscaping the gardens into a park, and being a true Scot, this included laying out a golf course too. Their fantastical, eclectically-styled mansion of 50-rooms sat at the centre of the 60-acre island estate that they connected to the mainland with a bridge guarded by a gatehouse. As Master of the Montreal Hunt, meets often gathered here in the season and polo was played in the summer. Paton stood out as being very popular with the local French-Canadians here.

Bob Carswell explained that Hugh Paton used a barge to get across the river to the Saraguay side. His family would spend summers on the island. Paton would take the barge to Saraguay, get on the polo road and take his wagon to his house in Montreal where he was at work on weekdays. Bob added:

If you look at that island today, if you look it up on the internet, you’d be able to see from there how all the high-rises have taken over, and you can look across the waters, and you see L’Île-aux-Chats, Cat’s Island, as we called it.

And there used to be a fellow, the family that owned Cat’s Island, lived at the bottom of my street. And they used to – the old man, the grandfather – used to go across the street to the island, in the winter when it froze over, and he would drag back these logs. He would take the logs up to Sainte-Geneviève and run them through a sawmill.

And that’s how they built their first house there. And he did this every winter, with Nellie, the horse’s name was, and she would tromp across and tromp back [with loads]. And then, of course, it became part of the Saraguay Woods, Le Bois-de-Saraguay, which is now a protected area, turned into a nature park, because there is so much flora in there that is so unique, that they literally protected the whole area.

Parc-nature du Bois-de-Saraguay

An online description of the Saraguay Woods park reads:

Parc-nature du Bois-de-Saraguay is located on the western part of the island, in Ahuntsic-Cartierville.

Parc-nature du Bois-de-Saraguay features unique natural and cultural riches. This large park is home to a variety of flora and fauna as well as a magnificent forest of rare ancestral trees scattered among water courses and wetlands. At the heart of its 96 hectares are two heritage buildings: the Mary Dorothy Molson house and the chauffeur’s residence of the former Ogilvie estate. Take a walk on the nature trail to discover the natural and historic treasures of this special place.

Hugh Paton made his money in the railway business. [6]

Sylvia Oljemark recounts how Bois-de-Saraguay was saved from destruction

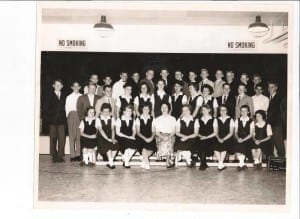

Graduating class, Cartierville School, probably 1959. Photo posted at MCHS ’60s Reunion Facebook Group by Howard Hight (MCHS 1963). The teacher in the photo is Mrs. Jackson of Saraguay.

At a previous post, Bob Carswell, referring to a 1959 Cartierville School class photo which includes Mrs. Mary Jackson, a teacher at the school, notes: “She [Mrs. Mary Jackson] and her daughter (Mrs. Sylvia Oljemark) were responsible for decades trying to get the City of Montreal to declare Saraguay as a Nature Park due to its unique Flora.” At the time of the post, the park had not yet been officially proclaimed. [7]

An excerpt (I’ve adjusted the paragraph breaks) from an online account by Sylvia Oljemark, entitled “Montreal’s Green Space Story: Past and Present,” reads:

Conservation efforts begin in the Village of Saraguay

Nineteenth century Montrealers were passionate about their parks. Neighbourhood parks and public squares abounded and the city’s pride, Mount Royal Park, was created in 1876. As the city grew through the early twentieth century, many parks were built over and Montrealers lost the political will to protect green space. It was not until the Montreal Urban Community came into being in 1970 that conservation possibilities were considered. Early in its tenure, the MUC identified parklands suitable for regional parks, but lacked the legal powers to implement the plans. At about the same time, other significant circumstances began to shape future events. Real Estate developers, having the forethought that our political class did not, had begun buying up tracts of vacant land.

Over the next fifteen years or so, the Grilli Corporation acquired almost all the undeveloped land in West Island. The Quebec Ministére des Transports was also purchasing swaths of land and establishing rights of way for future roads like the 440 Autoroute – in the interim unintentionally creating green corridors for flora and fauna so cherished by environmentalists. And some urban planner envisioned a major new artery, parallel to and roughly mid-way between Gouin Boulevard and the Trans-Canada Highway. The proposed artery was called de Salaberry Boulevard – a name that was to resonate till the present day. The original trajectory of de Salaberry was east-west from Cartierville-Ahuntsic to Kirkland. It looked good on a map, but two large urban forests stood in its path – Saraguay and Bois-Franc Forests. The stage was set for events to trigger Montreal’s first significant conservation efforts in a century.

The inspiration and impetus for the green space movement and its evolution into the Green Coalition began, quite by chance, in an obscure and little known community on the “Back River” (Rivière des Prairies) located about mid-way between the eastern and western tips of Montreal Island. The tiny Village of Saraguay, just a few streets wide, is nestled today between two large Nature-Parks, the Bois-de- Liesse and Bois-de-Saraguay. How that came to be and how Saraguay and its Forest became famous for a brief moment in Montreal’s history in the late 1970s attests to the mindset and sheer doggedness of Saraguay Villagers.

By the turn of the twentieth century, the industrial barons of Montreal’s Golden Square Mile had established large country estates and farms in Saraguay and environs for use during the summer. In Saraguay, these vast estates were managed as feudal fiefdoms with tied cottages to house their retainers – farmers, grooms, chauffeurs, butlers, maids and cooks. The wealthy land owners clubbed together to incorporate the Village of Saraguay as “a separate village municipality” in 1914, to maintain its unique rural aspect and, if truth be known, to keep out the ‘riff-raff’. Commercial development was outlawed. The only enterprise in Saraguay even today is the corner- store; formerly the Mic-Mac Restaurant; it acquired its rights before the incorporation.

In the early years, the Village of Saraguay was run like a private country club. But by the late 1940s, the old feudal order was crumbling. Service-men returning from World War II were not returning to their posts as faithful retainers on Saraguay estates; they were opting for taking up jobs in the city and for building modest homes on a tract of Saraguay farmland previously owned by Marcel Martin. Newcomers, like my parents, Tom and Mary Jackson, both school teachers, were also settling in the village center – called Shack Town by the wealthy land owners. Villagers were demanding a say in how Saraguay was run. In 1951, “commoners” were invited to join slates running for Council posts in the first election that followed due process. The Tom Jackson, Adrien Lecavalier, Hartland Campbell (Tommy) MacDougall slate, running on the platform “Keep Saraguay Beautiful”, carried the day.

Major developments threaten Saraguay

Whether they were conscious of the fact or not, old stock families, now independent of their wealthy overseers and the newcomers in the Village had developed a special pride-of-place, a distillation of the best intents of the 1914 incorporation and a determination to build an attractive, quiet, riverside community. In 1964, however, the Village of Saraguay, population 427, succumbed to the blandishments of Mayor Jean Drapeau who promised that Saraguay would maintain its “caractère champêtre et villageois” and the villagers voted in favour of a merger with the City of Montreal. In return, the village received water, sewage services; fire and police protection; before this time villagers had fought chimney fires by bucket brigade, losing several homes in the process! In 1967, with By-law 3470, Saraguay was zoned unifamilial résidentiel, entrenching the merger promise, and the charter of the Village of Saraguay was revoked. Saraguay’s wealthy estate owners had quietly begun to sell off their land holdings to developers. The old feudal era was at an end.

Local humourist Tom Jackson used to say, “Saraguay didn’t join Montreal, Montreal joined us”. He was more prophetic than he could have known. Just ten years later, to the consternation of Saraguay residents, the City of Montreal proposed a zoning change, that was already in second reading in July 1977 when the villagers heard of it. The entire Saraguay Forest was to be razed for the construction of housing, fourteen apartment blocks, two shopping centres, Twin Towers on Gouin Boulevard and the Port-Plaisance Marina Complex on the waterfront. Eighty-five hectares, at least half of Saraguay Ward was to be developed and a major road, the de Salaberry Boulevard, was to cut through both the village and the forest. So incensed were some residents that they wanted to ‘divorce’ Montreal and join Ville Saint Laurent. But, Mary Jackson mounted a hard-hitting media and citizens’ letter-writing campaign. The Mayor was presented with a petition signed by more than 95% of proprietors that I had circulated on my bicycle. On the eve of the third and final reading, Mayor Drapeau telephoned Mary Jackson with the news that the zoning change was to be withdrawn and that the Saraguay Forest was safe. He called again two weeks later with reassurances that the waterfront projects had been cancelled and de Salaberry shelved.

Bois-de-Saraguay piques interest of Québec government

It was to take several more years of intense work on the part of many groups and individuals before Saraguay Forest was truly safe. For example, the Société d’Horticulture et d’Ecologie du Nord de Montréal worked tirelessly for the conservation of Saraguay Forest as a “Parc Naturel Urbain”. The plight of the forest attracted the attention of the scientific community and numerous treatises were published on its exceptional ecological value. “La végétation et la flore du boisé de Saraguay” (Bouchard et Lacombe 1978) provides the definitive list of types of vegetation – 35 species of trees, 45 types of shrubs and 275 species of herbaceous plants; in addition, a dozen other vegetal species considered to be rare. Three amateur ornithological societies (Ducharme 1979) listed the birds of Saraguay – 129 species. For a time, because of these attentions, l’érablière à Caryer du Bois-de-Saraguay became Montreal buzz-words! The Bois-de-Saraguay came to be regarded as the bijou of Montreal’s green spaces – a pristine forest on the northern shoreline.

The Bois-de-Saraguay case is known in green space and bureaucratic circles as the “déclencheur” or trigger that set Montreal conservation in motion. According to André Bouchard at the Jardin botanique de Montréal, “The campaign to conserve Bois-de-Saraguay was the catalyst for the creation of the MUC regional parks network”. The furor over Bois-de-Saraguay piqued the interest of Quebec and in 1979, the Provincial Government granted MUC the mandate to acquire, manage regional parks, along with the legal mechanisms to do so. Quebec injected $10.5 million to start the acquisition program and an additional $2 million towards the Saraguay Forest purchase in 1981. During the first phase, between 1979 and 1982, Pointe-aux-Prairies, Ile-de-la-Visitation, Bois-de-Saraguay, Cap-Saint-Jacques, Bois-de- Liesse and L’Anse-à-l’Orme were acquired as Nature-parks. Subsequently the rhythm of acquisition slowed, although the establishment of park facilities continued.

One of the powers conferred by Quebec in 1979 was the capacity to impose Interim Control Bylaws to freeze commercial development on desirable parklands until funds could be found for their acquisition. The MUC placed controls on fifteen forested sites in 1982. However, within a few years the protection was lifted from three sites and they were lost to development. In Saraguay Village, folks were delighted that the natural sites that surrounded them were now protected in the Saraguay and Bois-de- Liesse Nature-Parks. They were cheered that the Quebec Government decreed the forested areas of Bois-de-Saraguay to be an Arrondissement naturel under the aegis of the Cultural Affairs Ministry in 1981, stipulating that no trees may [be] felled. No other Nature-Park has this special layer of protection.

Details regarding efforts (1977 to 2011) to save Bois-de-Saraguay

Details regarding the successful efforts to save the Bois-de-Saraguay can be found at this link:

Montreal’s Greenspace Story Chronological Notes: 1977 – 2011

An excerpt from the above-noted document reads:

1977: On a hot day in July 1977, my children came running home – shouting, “They are going to cut down Saraguay Forest.” Plans are in second reading. The forest is targeted for housing, 14 apartment blocks, 2 shopping centres, Twin Towers on Gouin, Port-Plaisance Marina on the waterfront: a major road – de Salaberry – is to cut through Village and Forest. Our family and neighbours form Saraguay Citizens Group; mount a media and letter-writing campaign; invoke Mayor Jean Drapeau’s merger promise that Saraguay would retain its “caractère champêtre et villageois.” More than 95% of proprietors sign a petition. The project is dropped: de Salaberry shelved.

1977-1979: Bois-de-Saraguay is the bijou of Montreal’s natural spaces – the scientific community extols its ecological quality: the Société d’Horticulture et d’Ecologie du Nord de Montréal campaigns for a “Parc Naturel Urbain.”

1979: “Déclencheur”: “The campaign to save Bois-de-Saraguay was the catalyst or déclencheur for the conservation of Montreal’s natural spaces and the creation of the regional parks network.” stated the late André Bouchard, professeur titulaire au Département de sciences biologiques de l’Université de Montréal et à l’Institut de recherche en biologie végétale. The furor over Bois-de-Saraguay persuades the Quebec government to grant the Montreal Urban Community the legal means and mandate to acquire, protect and manage regional parks (now called Nature-Parks). Quebec injects $10.5 million to kick-start the conservation measures.

Green Coalition webpage

Click here to access the Green Coalition webpage >

House at Derry and Trafalgar near Milton

At our Sept. 2, 2021 picnic, we spoke as well of an abandoned house near Milton west of Toronto, at the corner of Derry and Trafalgar Roads, that you can see from when driving south from Milton toward Oakville. I’ve devoted a previous post, which many people have read and some have commented upon, regarding the house, which appears to have been built in 1905. [8]

Whether the house warrants designation for its historic value, I have no idea. Whether people in the Milton area have been working together, now or in the past, seeking to preserve the building and repurpose it to some new use, I have no idea. What I know is that many people have been thinking about the building, as they drive by on their journeys to and fro over the years.

Dan McPhail commented:

Dan: It’s a nice house. When we first moved there [to Milton], there was people – when we first moved to Milton, there was a family in there.

Jaan: What year was that?

Dan: That would have been somewhere around – from 2004 to maybe 2007.

Jaan: That’s amazing.

Dan: And, if I can recall, they put in a swimming pool – like one of the above-ground swimming pools.

Jaan: Oh, yeah, that’s neat.

Dan: So, it wasn’t dormant that long and then, it just – and it was up for sale a couple of times.

Jaan: That’s really interesting. I looked around. There’s a few others off the main road, you know, that, again, are abandoned. But they’re beautiful houses, and you think of all the history.

What does the future hold for these abandoned houses?

Who knows what the future holds for the house at Derry and Trafalgar and other abandoned houses in the area. We can enjoy the houses just as they are; it’s of interest to contemplate their past and to experience their presence in the present moment.

It’s of interest to ponder the views looking east (toward the busy traffic on nearby Trafalgar Road) and west from the porch (toward farmers’ fields) of the house at Derry and Trafalgar. I can picture in my mind the backyard above-ground swimming pool (as described by Dan McPhail) of some years ago. I can picture the children at play outside the house. As Bob Carswell has said, a person can imagine that in a sense in every house the words are written: “Goodbye ol’ house.”

I also look forward to taking a road trip from Milton as Dan McPhail has suggested:

Dan: Jaan, if you have the chance, okay, go, drive along Britannia from Milton; go east along Britannia to 8th Line. Then make a right, and from Britannia Road down to Middle Road or something, it’s like driving – you can’t believe you’re in an urban area. It’s a road that’s been lost in time, almost, and it’s like driving in the country, and all the farms on the left, the farms on the right, and barns; it’s like a time out of history, you know.

Jaan: I’ll do that, for sure.

Dan: Because, what makes it so amazing its that it’s so close to industry, and building – you know, like subdivisions and things like that; it’s all by itself.

Preservation of Bois-de-Saraguay demonstrates the power of human agency

Human agency expresses itself in all kinds of ways. Sometimes, we just spin our wheels. At other times, we get some good traction and great things can be accomplished.

I’ve found it of much interest to learn about how the Saraguay Woods (Bois-de-Saraguay) came to be preserved. I come across the article by Sylvia Oljemark because Bob Carswell mentioned the Mic-Mac Restaurant, which prompted me to search online for “mic-mac restaurant saraguay.”

The story of Saraguay Woods underlines what I have learned, as an observer and occasional participant, in land use hearings in Ontario. I’ve learned that concerned citizens can have a powerful impact, of benefit to an entire community, when they work together effectively to make their voices heard.

In 2011, I was involved in a letter-writing campaign, assisted by strategic advice from several sources, which led to the saving of a Toronto school, named Parkview School at the time, as I’ve explained at previous posts.

I was involved, as well, in a letter-writing campaign that led to the designation, under the Ontario Heritage Act, of a historic house at 58 Wheatfield Road in Mimico, thereby ensuring its preservation, as I’ve also explained at previous posts.

I mention these two cases because I was directly involved and am aware of how important human agency was in these cases. There are many such cases; I’ve spoken about some of them at this website.

When I read recently about the preservation of the Saraguay Woods, I stopped to think about how much can be accomplished by people working together effectively, and I thought about how inspiring such stories are. I owe thanks to Bob Carswell for telling us about the Mic-Mac Restaurant. [9]

Note 1

A biographical sketch by Graeme Decarie at a previous post shares information about the life and times of the Very Rev. Malcolm Campbell, after whom the school is named.

Note 2

The situation is similar for digital versions of university newspapers from the same era. Some universities have set up such digital collections in such a way that the texts of old papers are easy to read whereas in other cases some of the texts are unreadable. This has to do with the quality of the scanning; some scans consistently yield text that is easy to read; some others yield text that is at times illegible. As well, the search engines for such collections work may work well or poorly, as the case may be.

Note 3

The Jim Tovey Lakeview Conservation Area in Mississauga is a more recent example of an infill project where land – in this case, wetlands – is being added to the Lake Ontario shoreline. In the latter case, however, the planning and scope of the project is decidedly more extensive (it involves the restoration of wetlands following a full environmental assessment) than the ad-hoc planning involved with infill projects in the 1950s in South Etobicoke.

Note 4

A June 14, 1961 Globe and Mail article, accessible through the Toronto Public Library website, is entitled: “New Toronto Mayor Critical of Inquiry.” Through reading between the lines, we can perhaps conclude that events that occurred in 1950 to 1960, which lead to Judge Ambrose’s inquiry in Mimico, may also have been a source of concern in New Toronto. I refer to an excerpt from the above-noted article:

The mayor of New Toronto objects to a judicial inquiry into Mimico’s building and zoning bylaws.

Mayor Donald Russell, at a meeting of New Toronto council last night, criticized the Ontario Government, the Ontario Municipal Board, and some Mimico citizens for their actions leading to the inquiry.

The inquiry, demanded by ratepayers, is scheduled to start early in July under Judge J. Ambrose Shea. Mimico Ratepayers’ Association claims that it can document up to 1,500 infractions of the building and zoning regulation since 1935.

Mayor Russell claims, however, that there “may be a little smoke there, but there’s no fire.”

His remarks came in discussion of a resolution aimed at ending the practice of having Mimico building inspector Jack Book substitute for New Toronto’s inspector, P.J. Fleming, during the latter’s holidays.

Councillor Harry Brown moved that issuing of building permits and inspections be discontinued this year while Mr. Fleming is on holiday.

In the past, he said, Mr. Book has substituted, but they do not want him to come this year because of unfavourable publicity concerning the probe.

Mayor Russell said he doubted that Mr. Brook had substituted for Mr. Fleming with council’s knowledge and he was positive that the Mimico inspector had not issued a permit in New Toronto.

“I think we may be getting a little hysterical in considering this resolution,” he said. “We know our community is clean and I think the other is clean, too, but because some disgruntled citizens have been complaining they can cause a judicial inquiry.

“I don’t know why the Municipal Board and the Ontario Government doesn’t have the fortitude to stop this sort of thing.”

The resolution was defeated 5 to 1 with Councillor Gordon Haycroft voting against the resolution he originally seconded.

Note 5

Aubrey Golden, a Toronto lawyer who represented the Mimico Ratepayers’ Association at the Shea Inquiry, speaks in a Feb. 23, 1963 opinion article in Maclean’s Magazine about the distinction between inquiries and courts of law:

As Mr. Justice McGillivray implied, “terms of reference” tend to be ignored by participants in public inquiries and the proceedings often become a partisan contest – without the safeguards of court rules. The no-holds-barred licence of commission hearings caused Judge Ambrose Shea, after presiding at an inquiry into the affairs of Mimico, a Toronto suburban municipality, to call for reforms. He warned that if rules for inquiry procedure were not laid down the next step would be to accept “rumor, gossip and the like” in lieu of evidence.

He asked for rules to govern the admission of evidence and pointed out that hearsay evidence – almost never permitted in court – is allowed at commission hearings.

This was not, of course, the first time a jurist had looked with disfavor on royal commission procedure. Exactly three hundred and fifty years ago Sir Edward Coke, the noted English judge, called for the abolition of royal commissions and warned against the “possibility of unrestrained libel and false accusation.”

I do not go as far as Sir Edward in arguing for abolition of commissions and judicial inquiries. People who support this form of inquiry make the point that often an inquiry is a necessary alternative to police-and-court law enforcement precisely because law enforcement has broken down as a result of police inefficiency, political interference, or even police connivance in lawbreaking. Commissions are necessary when doubt about the efficiency or honesty of law enforcement officials is part of the substance of the inquiry, as in the Ontario “crime commission” hearings and the Caron inquiry into Montreal’s police force.

But if commissions are the only way to get at such situations, what I and many other lawyers argue should be done is to impose half a dozen rules that would remove the worst of the inequities from present inquiries:

Establish the right against self-incrimination.

Prohibit hearsay evidence.

Establish beyond argument the right of witnesses to have counsel.

Provide persons likely to be affected with reasonable notice of the identity of witnesses and a summary of the nature of their evidence.

Allow at least forty-eight hours’ notice to persons summoned to testify.

Provide for hearing in camera testimony likely to be defamatory and for simultaneous release of the rebuttal. if any, with defamatory testimony.

Note 6

The website of L’Association Propriétaires & Résidants Pierrefonds – Roxboro Proprietors & Residents Association (APRPR) features details about Paton’s Island and the history of Saraguay and nearby communities.

At the website of L’Encyclopédie de l’histoire du Québec / The Quebec History Encyclopedia, you can read a biographical sketch of Hugh Paton, President of the Shedden Forwarding Company, Ltd., Montreal, Quebec.

Some other sources include:

Canada and Her Commerce (1894), pp. 116–18 and a Jan. 29, 1941 [Montreal] Gazette article entitled: “Hugh Paton is dead at his home here.”

Hugh Paton’s uncle John Shedden was the owner of John Shedden & Co. which built Toronto’s Union Station which was saved from demolition around the 1970s thanks to the efforts of concerned Toronto citizens.

Note 7

A July 15, 2020 Montreal Gazette article is entitled: “Saraguay woods officially become Montreal’s newest nature park: Montreal’s Saraguay woods were officially inaugurated as a nature park by city officials on Thursday — some 40 years after local citizens and environmentalists banded together to save it from being developed.”

An excerpt reads:

The marshy woods next to Gouin Blvd., east of Highway 13, were officially inaugurated as a nature park by city officials on Thursday — some 40 years after local citizens and environmentalists banded together to save it from being developed into highrise apartments, a marina and whatnot.

An additional excerpt reads:

The inclement weather didn’t dampen the spirits of local citizens and activists who spent decades fighting to preserve the woods and make them accessible to the public.

Local resident Jocelyne Leduc Gauvin called the forest the most beautiful in all of Montreal, and part of the city’s heritage.

“It was on a map of the island in 1702; it was called Beaubois, or beautiful woods,” she said.

“It was here when Montreal was founded in 1642 and was kept relatively intact through the years.

“Eventually, there were some prosperous families from the Golden Square Mile who established here, such as this (Molson) house. And they also protected the forest and used it for hunting and a polo club.

“In 1978, the land was put up for sale for highrise buildings. At that point, some groups started to say, ‘No, it must be saved.’”

Note 8

At the previous post of May 26, 2019, devoted to the house at Derry and Trafalgar, I refer to a book, Curated Decay (2017) which argues that some things simply can’t be preserved, in which case the option may be to enter consciously into the experience of watching them decay and fade away.

In general, we can say that some houses meet criteria set forth in the Ontario Heritage Act, and people have the capacity in some cases to mobilize the resources that are required in order to arrive at such a designation. At this website, I’ve documented a case in Long Branch, and another in Mimico, where such a designation has been achieved, with good results. I’ve also been documenting a case in Niagara on the Lake, where a heritage property has been designated under the Act, but for a variety of reasons, the next steps for the building remain to be determined.

Note 9

Demonstration of agency by residents

Update of Dec. 29, 2021 to this note:

We are dealing with power relations. We are dealing with social pragmatics, and with non-verbal as well as verbal behaviour. I base these comments on several decades of involvement in focused efforts to influence decision making in a wide range of volunteer projects at the local, national, and international levels.

In the early years, I spent little time articulating what I was aware of, with regard to such topics. In the past decade, however, in particular when I’ve stopped to think about the nature of human agency, I’ve begun to write about things that have guided my behaviour, in relation to power dynamics. In years past, I’d been applying such things without a lot of conscious thought.

It occurs to me that a point worth underlining is that in deputations related to land use decisions, the best way to approach communications is by maintaining a tone of level-headedness, diplomacy, and cordiality. That makes it easier for decision makers to make good decisions, in my anecdotal experience as an advocate and observer.

Expressions of anger and contempt may work well, as a way to channel and exploit anger, for populist politicians but in the representation of the interests of residents they are, in my view, counter-productive.

In terms of deputations I’ve seen at the City of Stratford and elsewhere, the most effective ones by far, from the point of power relations and outcomes, are the communications that are cordial and diplomatic. It’s been my observation that, as a general rule, the easiest request to turn down, the easiest representation to ignore, is the one that is characterized by anger and contempt.

The broader issue is power relations. Or power dynamics. That is, who can cause what to happen, under what circumstances? This is a topic I’ve been thinking about since I was a child. When I was in Grade 4 at Cartierville School, I pondered the fact that Mrs. Findlayson, who was the principal, was the person who appeared to have the most power in the school. You could sense it when she came walking down the hallway. I pondered what it meant, when a particular person has power in a given setting.

These are things that I think children figure out pretty quickly. As the years went by, I pondered how power dynamics make their presence known in everyday life. At first, I didn’t try to put into words what I was learning.

As the years went by, much later I settled (at least for now) on the concept of human agency, as a useful way to think about what goes on, say, when land use decisions are being made in cities (and rural settings) across Canada. I began to think about agency when I observed that some people have a lot of agency, and some have very little. I began to think: “What’s involved, in the demonstration of agency?”

In the past decade, through a combination of events, I’ve become particularly interested in land use as a topic that I can spend time pondering.

Prior to the past decade of thinking about land use issues, I spent 15 years in volunteer activities involved with community self-organizing.

A related concept (in addition to the concept of agency) is the idea that individuals and groups operate in accordance with particular perceptual systems, or characteristic ways of seeing, which in turn are connected with related forms of language usage, within particular configurations of power relations.

A basic thing that I’ve learned, primarily through attending land use hearings in Toronto over the past decade, is that sometimes power speaks its own language, whereby up is down, in is out, and big is small.

A corollary is that agency can be demonstrated in any of a wide range of ways, some of which are beneficial and some of which are harmful, depending on the vantage point of a given observer.

The current footnote is about how inspired I am regarding the history of Saraguay Woods, which I was delighted to have the opportunity to learn about over the past year.

At previous posts, accessible via this website’s search engine, I’ve described equally inspiring instances of residents, in locations elsewhere than Saraguay, who have also effectively demonstrated agency, in a most powerful and productive way.

Common elements in successful community self-organizing projects

All such efforts have things in common, in my anecdotal experience. You need an individual or core group of individuals with a vision, capable of bringing people together. You need to devote time to plan, prepare, consult, do research, investigate.

The work has to be spread out among many people, each with a strong sense of ownership of the project, as it’s usually too much for one or a handful to do on their own.

In my experience, with nonprofit organizations it’s vital to have a plan for leadership succession in place to ensure the project or organization has staying power. A culture of leadership succession is easy to set into place if the constitution and bylaws spell out clear provisions – such as term limits for senior leadership – to ensure leadership succession.

Otherwise, community groups come and go meaning that a community’s ability to represent its own interests is diminished. If the same group of leaders leads indefinitely, they grow old together without making provisions for a new leadership generation to emerge. Under such conditions when the longterm leaders fade away or pass away, the association is likely to pass from the scene as well, until a new generation comes along to start up a group from scratch.

Many groups have inspired me in recent years. There are many such groups and projects including across the Greater Toronto Area and beyond. You can learn about them at this website.

I can add the name of an individual who demonstrated agency in a huge way was Allan McDougall. A Feb. 20, 2019 Vancouver Sun obituary is entitled: “Obit: Canadian book legend Allan MacDougall dies at 71: He landed the Canadian rights to J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books, one of the most astute deals in the history of Canadian publishing.” Allan, who grew up on a Saraguay estate, was in my Grade 4 class at Cartierville School in the 1950s. I remember him as a good-natured student, with a great sense of humour.

Long Branch, Lakeview, Port Credit, Stratford, and Niagara on the Lake

In Long Branch, by way of example, the Long Branch Neighbourhood Association was launched some years ago starting with a preliminary survey of residents and a series of pre-launch meetings. The name of the association is the outcome of a survey question where residents chose from a list of names that had emerged from previous discussions.

The Long Branch Neighbourhood Association (LBNA) demonstrates that when members have a strong sense of ownership of an association, then they are motivated to support its work in every possible way. The sense of ownership matters hugely.

The LBNA has in recent years played a key role in a significant City of Toronto pilot project, involving development of the Long Branch Character Guidelines. The Guidelines have served to guide some aspects of land use decision making in Long Branch, at the Toronto Local Appeal Body, as I understand, which is a considerable achievement. Although I live in Stratford, I am an affiliate (non-voting) member of the association and strongly support its work behalf of residents of Long Branch and other Toronto neighbourhoods.

I’ve also written at this website about what Jim Tovey, John Danahy, and many others have achieved in getting development processes underway along the Mississauga waterfront. Projects now proceeding in Lakeview and Port Credit originated in a planning environment in which community interests were strongly taken into account. I’ve also written about how human agency has been strongly and productively expressed by community groups in Stratford and Niagara on the Lake.

A recent post about Stratford focuses on a current land use issue in that city; the post includes a link to an online video of a recent meeting of the city’s Heritage and Planning Committee. A presenter at the meeting noted that issues related to climate change are inseparable from current land use planning issues in a city such as Stratford. The online video also includes comments from several sources that a set of neighbourhood character guidelines would come in handy when future development proposals are presented for consideration by the city council.

Stratford residents have also done well in ensuring that a proposal for a floating glass plant was withdrawn some time back. The original plan, engineered by the city council, was to push through the proposal in such a way that public consultation about the project would be bypassed. When residents heard about the proposed bypassing of community consultation, they organized a successful and highly effective effort in opposition to the proposal.

More recently, the city has been making what appears to be good progress in moving a project forward, which focuses on the restoration and repurposing of Stratford’s Cooper Site, a huge railroad repair shop that has sat empty for many years.

In Niagara on the Lake, a key current issue concerns whether or not the Ontario Heritage Act has enough clout, in practice, to ensure that a historic property, the town’s Randwood Estate, which has been designated under the Act, is actually saved from destruction. As well, anecdotal evidence indicates that a set of neighbourhood character guidelines would come in handy in guiding future decisions involving land use in the Town of Niagara on the Lake.

Agency demonstrated by citizens of First Nations of North America

When I think about local history in Quebec, such as in relation to the Back River, Saraguay, and the Lake of Two Mountains, I also think about events – about what some observers label as the Oka Crisis – in Oka, Quebec, some years ago.

The expression of agency by Indigenous advocates in Oka and elsewhere, in response to settler colonialism inspires me tremendously.

Agency demonstrated by humanity since the European Enlightenment

When I think about all land use issues, now and in the past, I also think of the one big land use issue that subsumes – that is, that, in a sense, consumes – all other such issues: namely, the issue of the climate crisis. The agency that humanity has demonstrated with regard to ordering life on the planet since the Enlightenment has had a positive side and, of course, a side that is acutely problematic.

Regarding this topic, an Oct. 18, 2021 CBC editor’s note is entitled: “The planet is changing. So will our journalism: CBC News commits to doing even more climate change journalism.”

An excerpt reads:

The impact of climate on our changing planet may be the most pressing story of our time.

It is an environmental story, yes, but it’s also about health, the economy, jobs, energy, food, water, security, geopolitics, justice and equity. No sector will be spared its impact. Climate change will define every aspect of our lives and those of generations to come.

The consequences of increased greenhouse gas emissions from human activity should be a surprise to no one: According to projections by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Canada will experience increasingly warmer temperatures and more extreme highs; sea levels will rise on most of our coasts, causing greater coastal flooding and erosion; ocean acidification will increase; this country’s glaciers, permafrost and snow cover will decrease; hurricanes, storms and dust storms will intensify.

Our own research tells us that Canadians want to understand what’s happening (the facts and the science) and learn more about what can be done. There is a hunger for constructive solutions.

A Dec. 14, 2021 CBC article is entitled: “Quebec entrepreneur, 93, donates cherished island after protecting it from city sprawl: Nature Conservancy of Canada will protect Île Ronde habitat for birds and vulnerable turtle species.”

An excerpt reads:

Vikström has owned and cared for the land since the late 1960s, when he built his family home in Laval and fell in love with his view of the island. He convinced its former owner to sell, so he could keep it untouched.

His recent donation ensures it will be protected for generations to come.

“I trust my children; I’m sure they’ll protect the island. But what happens after my children [are] gone?” Vikström said in an interview with CBC News at his home in Laval, Que.

“It’s just a good feeling in my heart. I know this will be there forever.”

The following note elaborates on a reference to David MacDougall in Note 9 above.

The current post includes a reference (from an online document about Saraguay authored by Sylvia Oljemark) to the MacDougall family:

In the early years, the Village of Saraguay was run like a private country club. But by the late 1940s, the old feudal order was crumbling. Service-men returning from World War II were not returning to their posts as faithful retainers on Saraguay estates; they were opting for taking up jobs in the city and for building modest homes on a tract of Saraguay farmland previously owned by Marcel Martin. Newcomers, like my parents, Tom and Mary Jackson, both school teachers, were also settling in the village center – called Shack Town by the wealthy land owners. Villagers were demanding a say in how Saraguay was run. In 1951, “commoners” were invited to join slates running for Council posts in the first election that followed due process. The Tom Jackson, Adrien Lecavalier, Hartland Campbell (Tommy) MacDougall slate, running on the platform “Keep Saraguay Beautiful”, carried the day.

The reference brings to mind an earlier post which refers to the MacDougall family:

Additional comments from Graeme Decarie – regarding Saraguay, Cartierville School, and Marlborough Golf Club

An excerpt reads:

Cartierville School

Jaan Pill: I also remember a child in my class in Grade 4 at Cartierville School who lived in a very nice house by the Back River, a huge house with a big lot. I learned quite recently that his grandfather was the local physician, and learned a bit about what he did in the course of the subsequent years.

Bob Carswell provided a great update for me:

“Jaan, You mentioned a school friend. You are talking about Allan MacDougall, cousin to Jamie Duncan, and part of the old Saraguay family there. It was his grandfather Dr. Duncan that delivered my own father into this world. Allan moved out to Vancouver, set up a book distribution firm and ended up the North American distributor for the Harry Potter books. He is also a on the Board of Directors of the Vancouver Library System along with a good friend of my youngest brother, also in Vancouver.”

A Dec. 8, 2022 CBC article is entitled: “‘The fight is on to protect urban wildlife in Montreal’: Local ecologists say city green spaces need to be a habitat for native species and a sponge for rainwater.”

An excerpt reads:

Volunteers like Breier are vital to Montreal’s urban biodiversity, according to local ecologists who hope the attention from the city hosting COP15 this month will lead to the expansion of more green spaces on its territory, and more citizen involvement in maintaining them.

They want officials around the world to understand the importance of supporting wildlife — not just outside of cities, but within them as well.