Reading series of plays-in-translation features some of the best of Ukraine’s theatre, created since the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion – Stratford Festival, Sept. 23-24, 2023

Updates: A subsequent post is entitled: Many Russian studies programs have engendered serious academic ignorance – regarding Ukraine and its neighbours: Tomasz Kamusella, New Eastern Europe, Aug. 11, 2023.

A Jan. 28, 2024 Toronto Star article is entitled: “Two years after reopening from the pandemic, is Toronto’s theatre sector on the brink of a crisis?: Unless there’s a turnaround, arts leaders say the city’s once-thriving sector could become a shell of its former self.”

An excerpt reads:

Canada’s largest repertory theatre company, the Stratford Festival, said that 2023 was a “very successful” season, though it’s not yet back to pre-pandemic levels. “We are heading into 2024 with optimism,” said executive director Anita Gaffney. The festival did not provide exact attendance figures, but said they will be available later in the spring.

*

At a previous post, I have outlined a panel session – part of a series of Meighen Forum events in September 2023 – which described the ongoing work of Ukrainian playwrights and artists in the 19 months since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022. I have also shared links to several resources:

Larzaridis Hall – in middle of figure: venue for Meighen Forum events. Detail from architectural plan on display at Festival Theatre, Sept. 7, 2019. Source: Hariri Pontarini Architects. Jaan Pill photo

An Anthology of Modern Ukrainian Drama

A Dictionary of Emotions in a Time of War: 20 Short Works by Ukrainian Playwrights

Some additional resources include:

Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine

Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies

Ukrainian New Drama after the Euromaidan Revolution

Source: Hariri Pontarini Architects CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE IT

Tom Patterson Theatre under construction

Architectural model. Source: Hariri Pontarini Architects.

At another previous post, I have outlined the connection between the land use history of Stratford dating back to the late 1800s and early 1900s and the subsequent launch – within a pastoral parkland setting – of the Stratford Festival on July 13, 1953:

Stratford, Ontario: Canada’s cultural tourism destination

Architectural model on display at Festival Theatre, May 7, 2019. Source: Hariri Pontarini Architects. Jaan Pill photo

At the current post, I will focus on three things that come to mind, as I look back on the two Forum events I attended on the weekend of Sept. 23-24, 2023.

Architectural model at Festival Theatre, Sept. 22, 2019. Source: Hariri Pontarini Architects. Jaan Pill photo

This post also feature photos of the Tom Patterson Theatre under construction. I have, as well, included photos of a tent installed at a theatre parking lot on the east end of the site, when – as a consequence of the COVID pandemic – plays were not being staged indoors.

Architectural model at Festival Theatre, Sept. 22, 2019. Source: Hariri Pontarini Architects. Jaan Pill photo

At the time when the tent was in place, my wife and I attended The Rez Sisters followed by a discussion which took place indoors at the theatre. I was very impressed with this play – it provided a strong sense of immersion in experiences and reflections that I otherwise would not know about – and I was inspired and energized by the ensuing discussion.

At the events I attended on Sept. 23-24, 2023, some people (me among them) were wearing masks; most attendees at such events do not wear masks. I am pleased that some people do wear them.

Verbatim theatre, cultural imperialism, and cultural genocide

Several things stay in mind from the panel on Sept. 23, 2023. First, I was prompted to learn more about verbatim theatre. After I got home from the event, I read a research article (discussed below) published in 1987 which outlines the early history of this genre.

The article notes that radio ballads of the 1950s and the British documentary film movement of the 1930s and 1940s were among the precursors of this form of theatre.

I was reminded, on reading the article, that his work on historical radio drama in the 1930s had been a major influence on how Tyrone Guthrie, the first artistic director of the Stratford Festival in the early 1950s, came to approach the staging of drama.

In particular, there is a connection between Guthrie’s experience with radio drama and his active involvement in the years that followed, with the design of the thrust stage (which features minimal scenery) at the Festival Theatre as I have outlined in a previous post:

Recasting History (2019) features informative analysis of CBC profiles of Canadian history

Secondly, from the above-noted panel session, I became better aware of how cultural imperialism can be posited as representing a key feature of empires in history such as the British, French, and Russian empires. That is, in such empires, culture has served as a cover – as a smokescreen, so to speak – for devastation and destruction directed at the original inhabitants of empires under consideration. What is at play can be characterized, in my understanding of the power dynamics involved, as a form of gaslighting – a method of scamming.

I have thought about this topic previously, in particular in the context of the British empire, after about a dozen years of reading studies dealing with the latter empire. I’ve also been aware that past studies of the Russian empire in Western universities have at times glossed over the concept – over the reality, in fact – that as with other empires, the Russian empire demonstrated a strong element of cultural imperialism. It was of interest to hear relevant themes, related to the Russian empire, discussed in comprehensive depth at the above-mentioned panel.

Academic programs focusing on Russia, Central Europe, and Eastern Europe

Since attending the panel, I have read several articles about how Russians studies – and studies focusing on Central Europe and Eastern Europe – have been approached in academic settings in the West in the past and how they are being approached now.

For example, I have been reading an August 11, 2023 New Eastern Europe article by Tomasz Kamusella entitled “Going native: Russian studies in the West: The West’s endorsement of Russian imperialism comes in different forms, sometimes taking on the guise of ‘Eastern European studies’ in renowned centres of learning.”

An excerpt reads:

During the summer following Russia’s unprovoked invasion of peaceful Ukraine in 2022 I did research at Hokkaido University in Japan at the Center for Slavic-Eurasian Research (SRC). It is the country’s oldest institution for delving into and gathering intelligence about the Soviet bloc and now the post-Soviet and post-communist countries. Immediately after the post-war US occupation of Japan in 1952, Washington turned this country into a stalwart of the West in the Cold War confrontation. To increase its value as a US ally, Tokyo needed trusted expertise on all matters Soviet, necessitating the founding of the SRC, with was accomplished with much American help.

Columbia University’s Russian Institute (established in 1946 and now known as the Harriman Institute) served as a ready-made model. In both cases, the Rockefeller Foundation extended appropriate grants. Symbolically, the SRC was located in Japan’s northernmost island of Hokkaido, which the Kremlin had aspired to either annex or occupy at the end of World War II. In the latter scenario, the Soviets would have created a communist North Japan, as they did in the case of the communist polities of North Korea and North Vietnam. Fortunately for Japan and the free world, the Soviet designs were thwarted.

Russian or Area studies?

Each year, from all around the world, the SRC invites promising and established scholars who specialize in the history, culture and politics of the region as defined by the centre’s spatial remit, namely Central and Eastern Europe, together with Northern and Central Asia. During my scholarly sojourn in Sapporo, I had the privilege to talk to the current contingent. In the context of the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war, we reflected on Russian propaganda’s use and abuse of Russian literature for “justifying” Moscow’s neo-colonial onslaught in Ukraine.

Additional articles addressing similar themes related to the current war in Ukraine include a June 21, 2023 Berkeley News article, “Why Russian studies in the West failed to provide a clue about Russia and Ukraine.” The article is by Yuriy Gorodnichenko co-authored with Ilona Sologoub and Tetyana Deryugina.

An excerpt reads:

Writers such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Joseph Brodsky were not sufficient in reassessing the Soviet past. As a leading cultural figure criticizing Stalinism, Solzhenitsyn was also a prominent imperial nationalist who called for the annexation of northern Kazakhstan and denied Ukraine’s cultural autonomy. Likewise, Brodsky, the intelligentsia’s spiritual idol, refused to recognize Ukraine as a sovereign nation.

A third article addressing similar geopolitical themes is in the form of an April 22, 2022 policy memo (No. 771) by Botakoz Kassymbekova from PONARS Eurasia: New Approaches to Research and Security in Eurasia. The article is entitled “Time to question Russia’s imperial innocence.”

An excerpt reads:

Nations formerly under Soviet occupation increasingly oppose Putin’s longing for Soviet order. From Ukraine to Georgia and Kyrgyzstan, decolonial discourse is rapidly expanding into the mainstream. In Ukraine and Kazakhstan, the horrors of mass starvations that killed millions reveal the unimaginable human cost of the Soviet regime. Academics in Georgia and Kyrgyzstan are reexamining the purges of elites, increasingly calling both Tsarist and Soviet Russia imperial powers. The war in Ukraine accelerated decolonial discourse. The renewed interest in the past has revealed the unpleasant hierarchies of the Soviet regime and eroded the Soviet construct of Russia as an altruistic nation, sacrificing itself for the sake of non-Russian republics. Instead of seeing the Soviet regime as a gift of modernity, more people are inclined to see Soviet Russia as a brutal colonizer.

Land Acknowledgement

Through my reading as soon as I got home from the panel, I have also become better aware of what cultural genocide, which historically has been connected with cultural imperialism, entails.

The Land Acknowledgement at the panel was based, if I recall correctly, on the version which appears at the Stratford Festival website which reads:

Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity – and therefore storytelling – for many thousands of years.

This territory is governed by two treaties. The first is the Dish With One Spoon Wampum Belt Covenant of 1701, made between the Anishinaabe and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, an agreement to set violence aside and peacefully share and care for the land in the Great Lakes Basin. The second is the Huron Tract Treaty of 1827, an agreement made by eighteen Anishinaabek Chiefs and the Canada Company, an agency of the British Crown. As an organization and as individuals, we at the Stratford Festival are in a process of learning how we can be better treaty partners.

We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples to share and care for this land for generations to come.

A suggestion was made after the Acknowledgement, if I recall correctly, that attendees make a point of learning about the recommendations of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015). I did not take notes at this point, meaning that I do not know if I recall this detail correctly.

At any rate, I have now been reading Volume One: Summary, of the above-noted Report, beginning with the Calls to Action (pp. 319-37). I find it of interest to learn about Indigenous history; when I was growing up in Montreal and in later years I learned next to nothing about Indigenous history in school or in my reading of history. Only much later did I begin to study such a topic.

I also read a passage (p. 1, Volume One of the above-noted Report) which defines cultural genocide as “the destruction of those structures and practices that allow the group to continue as a group. States that engage in cultural genocide set out to destroy the political and social institutions of the targeted group.”

“Land is seized,” the definition notes, “and populations are forcibly transferred and their movement is restricted. Languages are banned. Spiritual leaders are persecuted, spiritual practices are forbidden, and objects of spiritual value are confiscated and destroyed. And, most significantly to the issue at hand, families are disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next.”

Aug. 14, 2021. Tent near Morenz Drive and Lakeside Drive at Tom Patterson Theatre during COVID shutdown. Jaan Pill photo

The first page of Volume One of the Report also notes that “Physical genocide is the mass killing of the members of a targeted group, and biological genocide is the destruction of the group’s reproductive capacity.”

Cultural genocide directed at Indigenous peoples worldwide is a central feature of world history. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine starting on February 24, 2022 similarly demonstrates features of cultural and other forms of genocide. In previous posts, I have discussed genocide – as a concept, and in relation to another concept, namely, the notion of extremely violent societies.

Click here for previous posts about genocide >

The Rez Sisters

I attended The Rez Sisters which was staged in a tent on the grounds of the Tom Patterson Theatre on Aug. 11, 2021. I also attended the post-play discussion facilitated by Kelly Fran Davis, Haudenosaunee of the Cayuga Nation Wolf Clan from the Grand River Territory, which followed in a spacious meeting room next to Lazaridis Hall.

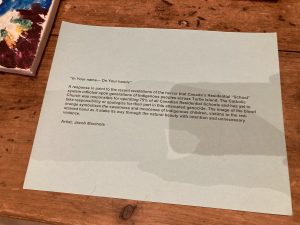

The painting by Jacob MacInnis which I have posted is entitled: “In Your Name – On Your Hands.” The painting was on display during the discussion we attended after The Rez Sisters play. The description for it reads:

A response in paint to the recent revelations of the horror that Canada’s Residential “School” system inflicted upon generations of Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island. The Catholic Church was responsible for operating 75% of all Canadian Residential Schools and has yet to take responsibility or apologize for their part in this attempted genocide. The image of the blood orange symbolizes the sweetness and innocence of Indigenous children, victims to the red-stained hand as it stabs through the natural beauty with intention and unnecessary violence.

Oral history and documentary techniques

Since attending the panel, I have also read an article published in 1987, ‘Verbatim Theatre’: Oral History and Documentary Techniques by Derek Paget. The citation link is: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266464X00002463

The abstract reads:

‘Verbatim Theatre’ has been the term utilized by Derek Paget during his extensive researches into that form of documentary drama which employs (largely or exclusively) tape-recorded material from the ‘real-life’ originals of the characters and events to which it gives dramatic shape. Though clearly indebted to sources such as the radio ballads of the ‘fifties, and to the tradition which culminated in Joan Littlewood’s Oh what a Lovely War, most of its practitioners acknowledge Peter Cheeseman’s work at Stoke-on-Trent as the direct inspiration – in one case, as first received through the ‘Production Casebook’ on his work published in the first issue of the original Theatre Quarterly (1971). Quite simply, the form owes its present health and exciting potential to the flexibility and unobtrusiveness of the portable cassette recorder – ironically, a technological weapon against which are ranged other mass technological media such as broadcasting and the press, which tend to marginalize the concerns and emphases of popular oral history. Here, Derek Paget, who is currently completing his doctoral thesis on this subject, discusses with leading practitioners their ideas and working methods. Derek Paget teaches English and Drama at Worcester College of Higher Education, and has also had practical theatre experience ranging from community work to the West End, and from Joan Littlewood’s final season at Stratford East to the King’s Head, Islington.

Project: Humanity

The recent weekend series of events was curated by Andrew Kushnir who as noted at a previous post, “is an award-winning playwright, director, and activist who lives in Toronto. He is artistic director of the socially engaged theatre company Project: Humanity, a leading developer of verbatim theatre in Canada.”

Click here to access the Project: Humanity website >

An anthology of new drama since the Euromaidan Revolution

Andrew Kushnir said that after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022, Stratford Festival’s artistic director, Antoni Cimolino asked Kushnir, “What can the Festival do?” The weekend series of well-organized events was the outcome of the ensuing planning.

Kushnir referred to a book entitled Ukrainian New Drama after the Euromaidan Revolution (2023). A blurb reads:

Ukraine’s remarkable aptitude for resilience and grassroots activism, as witnessed since February 2022, is closely connected to a process that began with the Euromaidan Revolution in 2013-14, when over two million Ukrainians took to the streets in defense of democracy and human rights. In the months directly following the Revolution, Russia illegally occupied Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula, and began funneling both arms and troops into the eastern region of Donbas to fuel a conflict between the Ukrainian army and a small group of radical separatists. Since that time, Ukrainians have been working diligently to build the society in which they have wanted to live, all while fighting Russia and its proxies in Europe’s forgotten war.

Ukrainian New Drama After the Euromaidan Revolution brings together key works from the country’s impressively generative post-Revolutionary period, many of them published here in English for the first time. As well as established voices from the European theatre repertoire such as Natalka Vorozhbyt and Maksym Kurochkin, this collection also features iconic plays from Ukraine’s post-Maidan generation of playwrights Natalka Blok, Andrii Bondarenko, Anastsiia Kosodii, Lena Lagushonkova, Olha Matsiupa, and Kateryna Penkova. Considered together, these plays reflect the diversity of voices in Ukraine as a country seeking to comprehend both the personal and political consequences of the Revolution, the war, and all that has come since.

A key element to the remarkable culture of defiance and resistance that Ukrainians created in these years has been new approaches to arts activism, particularly in the performing arts. In the eight years between Euromaidan and the full-scale invasion, Ukraine witnessed an incredible boom in socially engaged performance practice. Playwriting in particular has become an essential genre through which artists have sought to bear witness to the repercussions of the war and to create spaces for the reclaiming of historical and cultural narratives; Ukrainian New Drama After the Euromaidan Revolution captures this spirit and published this necessary and vital work in English for the very first time.

Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine

As well, Kushnir spoke about the Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine which is hosted by the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies.

Kushnir attended a Ukrainian camp in Quebec when he was an adolescent. He said that, looking back, it was clear that at such camps, Ukrainian “culture was being baked into us by our grandparents.”

The panel spoke about “eternity and the eternal” as a big theme in Ukrainian cultural expression. It was noted that such a theme has been common worldwide “among many cultures that have faced erasure.”

“Why is Canadian Theatre So Russian Right Now?”

I was interested to learn of a Feb. 24, 2023 Intermission article by Kushnir, entitled Why Is Canadian Theatre So Russian Right Now? The article appeared on the one-year anniversary of the invasion which began on Feb. 24, 2022.

An excerpt reads:

I’m curating a Ukrainian play reading series for the Stratford Festival slated for September. I developed this idea with them as I struggled with how little our theatres seemed to be engaging with the genocidal war unfolding before everyone’s very eyes. I had initially chalked this up to whataboutism (“what’s happening in Ukraine is awful, but what about the other awful things in the world?”), which so often leads to sitting on one’s hands about everything. But then I came to see how academic institutions and theatres in the UK have rallied madly to commission and translate Ukrainian playwrights and get readings – even productions – on their feet. The Metropolitan Opera in New York dedicated the remainder of their 2022 season to “Ukraine, its brave leaders, citizens, and artists;” a New York theatre company has programmed one of my just-finished plays for an annual festival of theirs. Director and translator John Friedman’s highly successful Worldwide Ukrainian Play Readings initiative has had 74 affiliated theatre events in the States since March 2022, 47 in the UK, and 43 in Germany.

To date, Canada has had three.

Canada boasts the second largest Ukrainian diaspora in the world — second only to Russia, in fact. Why hasn’t this diaspora been met by our theatre scene in what is arguably its greatest moment of need?

Click here for a link to John Friedman’s work (also spelled Freedman) >

I have previously written posts about totalitarianism.

Among such previous posts is one entitled:

Beyond Totalitarianism (2009) features specialist essays comparing Nazi and Stalinist mass murder in the 1930s and 1940s

I recently came across a Sept. 11, 2023 New Eastern Europe article entitled “Orwell’s warning of totalitarianism for today: A review of George Orwell and Russia.” The book under review is by Masha Karp; it is published by Bloomsbury Academic.

An excerpt reads:

In the following years Orwell frequently struggled to print what he thought about the Soviet regime. It took him three months in 1944 to write his “fairy story’” – Animal Farm – but another six to find a publisher. Editors were reluctant to bring out books which criticised Britain’s valiant war-time ally. And the English intelligentsia swallowed and repeated Russian propaganda, Orwell complained, much of it fuelled by Soviet agents.

One of Orwell’s influential friends was the Vienna-born sociologist Franz Borkenau. A convinced Marxist, Borkenau wrote secret reports for the Comintern in Berlin. In 1928 he broke with Moscow, which had identified Germany’s Social Democrats rather than its Nazis as the main enemy. Orwell and Borkenau reviewed each other’s books. It was Borkenau who argued that Bolshevism and fascism were slightly different specimens of the same dictatorship.

Old habits

Seven decades later, authoritarian habits returned to Russia. A handful of experts, human rights activists and journalists tried to draw attention to the Kremlin’s reversion under Putin into a repressive war state. Karp was one of them. “They were not heard,” she laments. There was plenty of evidence: the murder of critics at home and abroad, two Chechen wars, and the 2008 invasion of Georgia. Of course, later this was followed by the 2014 annexation of Crimea and Putin’s covert takeover of a part of the Donbas.

Karp suggests that it was western analytical error and complacency which made Putin’s attack on Ukraine possible. Contemporary policy makers and politicians were guilty of “an incredible lack of political judgement coupled with unfettered greed”. Deputies, British peers and other unscrupulous individuals “grabbed profits” offered by the Russian authorities. On top of this came Russia’s “skilful propaganda” and “deep infiltration” of our democracy.