What you thought about the Boer War of 1899-1902 depended largely on where you were living, at the time

In working on a biography which focuses on Alberta, I’ve been giving a lot of thought to matters involving public history, historical memory, and the means by which we arrive at mental pictures of the events of long ago. Many conceptual frameworks are available to choose from, when we seek to understand history.

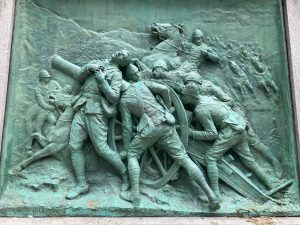

Boer War monument in Montreal

In a previous post I describe a British empire monument unveiled in Montreal in 1907, dedicated to Canada’s involvement in the Boer War. The history of the Boer War is part of the history of the British empire.

It occurs to me, in this context, that it’s a great idea to picture a continuum of contrasting options, when we consider how a range of historians have approached the history of the empire.

At the one end of such a continuum, the British empire can be viewed as akin to a big happy family, where everybody knew their place inside of a hierarchy based upon class and status – and regarding which it has been claimed that everybody had a comforting sense of belonging.

At the other end of such a continuum, the empire can be viewed as a vast, all-encompassing enterprise which was structured in accordance with a rigid, all-pervasive, and brutal system of organized violence.

George Orwell has brought attention to the latter end of the continuum.

On the other hand, it may also be emphasized that the legacy of violence of the British empire – including, indeed, what the contemporary historical record has documented as its extensive experience, during its colonial heyday, in the incessant waging of pervasively lawless, irregular warfare – was productively brought to bear on the Allied side during the Second World War.

Detail: Battle of Komati River – Belfast. Boer War monument, Dorchester Square, Montreal. Jaan Pill photo

Boer War sources

To learn about the Boar War, many sources are available.

You can read A People’s History of Quebec (2009) regarding how the war was viewed in French Canada. You can also read The Routledge Handbook of the History of Settler Colonialism (2017) which features chapters on the settler colonial history of South Africa.

Another study is entitled: The Inheritors: An Intimate Portrait of South Africa’s Racial Reckoning (2022). This evocative study, a form of literary nonfiction, which may also be termed narrative nonfiction, is well worth reading – I’ve learned a lot from reading it – albeit it’s put together without the standard academic notes that would specify sources. That said, the book features a comprehensive Selected Bibliography – and a list of people with whom the author engaged in Personal Conversations.

I highly recommend this book – it brings to life a range of stories centred on the history of South Africa. When you read such a book, you’re reading something that’s up-close and tangible (so to speak). The book speaks of the Boer War as the Anglo-Boer War.

Systems of citation

If I recall correctly, in Confidence Man (2022) you have a citations arrangement that works well, without the use of a subscript numeration system which would serve to clutter up the text. The end notes at the back of the book enable a person to quickly figure out the source for a given quotation, paraphrase, or statement of fact. The latter approach to citations works well. The text is not cluttered with a system of numeration; yet the end notes clearly indicate, in bold print, which phrase or quotation in the text is being cited.

The same citation system – in this case, with end notes in a two-column format for even greater ease in reading – is evident in the biographies of Robert Caro.

Such an approach underlines two things: Evidence matters to many readers (which is why citations are used in many works) as does the experience of the end user of the product – in this case, the reader.

British empire had strong influence on history of Middle East

When a numbering system is in place, and where the end notes specify where to find the notes for each set of specified page numbers, you have an even easier way to keep track of citations. It’s also a way where notes of various kinds (aside from citations) can readily be indicated.

An example is found in The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917-2017 (2020) by Rashid Khalidi.

With regard to the latter study of history, I was interested to come across a Dec. 16, 2023 Politico article entitled: “Masha Gessen Kicks the Hornet’s Nest on Israel and the Holocaust: In a new Q&A, the Russian-American journalist discusses why a prestigious award ceremony for them got called off.” An excerpt from the article reads:

In Gessen’s view, Germany’s rigid definition of antisemitism, however well-intentioned, has had the effect of stifling valid debate, particularly about Israel. And it has implications for the current debate in the United States over what constitutes antisemitism, and what speech or language is acceptable.

Massha Gessen’s work is also highlighted at a previous post about totalitarianism.

Additional Boer War sources

You can also read about the Boer War in the Canadian Encyclopedia, in Encyclopedia Britannica, and in Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire (2022).

Click here for BBC South Africa country profile >

Click here for BBC South Africa profile – Timeline >

Click here for BBC updates about South Africa >

British scorched earth policy

A Canadian Encyclopedia article about the Boer War refers to the British scorched-earth strategy, instituted to counter the Boer insurgency during the war:

By June 1900, Bloemfontein and Pretoria had fallen to the British and Paul Kruger, the Transvaal president, had fled to exile in Europe. But rather than surrender, the remaining Boer forces organized themselves into mounted guerrilla units and melted away into the countryside. For the next two years the Boers waged an insurgency against the British – raiding army columns and storage depots, blowing up rail lines and carrying out hit-and-run attacks. The British responded with a scorched-earth strategy – burning farms and herding tens of thousands of Boer and African families into concentration camps, until the last of the “bitter enders” among the Boer fighters were subdued.

A more detailed account – which is written in a tone that differs from that of the above-noted account – of the British scorched earth policy is available in Legacy of Violence (2022). The second account begins with a description of the state of affairs in 1900, after the British had taken nominal control of the Boer Republic:

Now the war moved into its final phase as Afrikaners adopted a highly effective guerrilla strategy. To close the war, [Horatio Herbert] Kitchener took full charge of the army as commander in chief and launched an all-out assault on an entire ethnic population: or as Kipling termed it, a “dress parade for Armageddon.” [21] The British Army introduced a new blockhouse strategy that, combined with barbed-wire fences, divided the massive interior into smaller areas. Kitchener then deployed a scorched earth policy and systematically burned crops and dumped salt to prevent future cultivation. Sweeper columns mopped up any residual Afrikaner forces. Kitchener eventually deported thirty thousand prisoners of war to remote corners of the empire. [22] British troops also razed homesteads, poisoned wells, and corralled into concentration camps Afrikaner women and children as well as African laborers.

Oxford County Gaol as it appeared before the building was repurposed as Southwestern Public Health. Jaan Pill photo

Elkins (2022) notes that in pursuing such a policy,

Kitchener was drawing on imperial precedents: this was not the first time the British Empire had sought to solve a crisis through mass encampment. Since 1857 officials in India had experimented with a series of confinement measures that were as much about reform as they were about security and punishment. The Indian Mutiny had spawned the mass incarceration of twenty thousand rebellious subjects whom British officials exiled to the Andaman Islands. There, sparse tented conditions and forced labor were to impart a sense of Victorian-era rehabilitation.

Elkins (2022) adds that a nineteen century British principle advocating the temporary “separation” of “dangerous” segments of the population was a key element in the “mass encampment” policy:

Indeed, temporarily separating “degenerate” and “dangerous” segments of the population from the body politic was a hallmark of nineteenth century Britain. The Poor Law of 1834 and the Habitual Criminals Act of 1869 created social categories of Britons who, like the empire’s subjects, were part of liberalism’s underbelly. It wasn’t just a matter of incarcerating these threats to society; it was also to be an exercise in reforming them through hard physical labor, thus rendering them more rational and civilized. The Raj imported these ideas through legal mechanisms – it translated Britain’s Habitual Criminals Act into India’s Criminal Tribes Act – as well as through camp systems that reflected the metaphorical language of contagion.

Click here for Encyclopedia Britannica article about Horatio Herbert Kitchener >

Boer War monument in Woodstock

A previous post features a Boer War monument in Montreal. The current post features a Boer War monument in Woodstock.

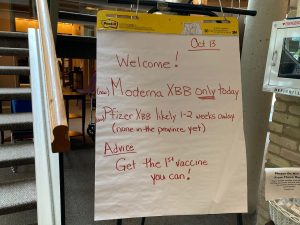

I visited the city on Oct. 13, 2023 to get a COVID vaccination at Southwestern Public Health, which is located inside a former Oxford County jail building. The building is next to the Oxford County Court House concerning which a plaque reads:

The Oxford County Court House

The first Court House built on this site in 1839 served the District of Brock and later the County of Oxford. It was replaced in 1890, but this Court House was not completed for 3 years. Council held their first meeting on December 6, 1892. Building plans and financial problems delayed the construction. It is an outstanding example of late Victorian Victorian style of architecture.

Woodstock District Chamber of Commerce and Oxford Historical Society – May 1976

During my October 2023 visit to the city, I learned new things about Woodstock. Previously, I was only familiar with the city’s Southside Park.

Click here for details about the Oxford Rifles >

Click here for details about the Oxford County Jail >

Click here for details about the Oxford County Court House >

An inscription on the Boer War monument at the Oxford County Court House reads:

Colour-Sergeant George W. Leonard, 22nd Rec. (The Oxford Rifles). A private in the 2nd (S.S.) Batt. R.C.R. who died May 11th of wounds received at Zand River, South Africa on May 10t 1901.

This memorial was erected by the people of the City of Woodstock and the County of Oxford.

Apartheid in South Africa

Chapter 20 in the Routledge Handbook of the History of Settler Colonialism (2017) outlines how, eventually, the Afrikaners minority gained power in the decades after the Boer War and ran South Africa according to the principles of apartheid until the mid-1990s.

At that point, the powers that be could no longer maintain power given the overwhelming anti-apartheid resistance of a majority of the country’s population. A drastic change of government – and of legislative statutes – ensued. The Inheritors (2022) updates the ongoing post-apartheid story of South Africa as it has continued to evolve, closer to the present day. Much of the discussion involves the language of psychotherapy and counselling, which can be a great way to deal with a range of perceptions, within a literary overview of relevant issues.

A Little History of Canada (2011, 2017)

A Little History of Canada by H.V. (Henry Vivian) Nelles is another good place to start in the event a person seeks a quick overview of how the Boar War affected Canadians.

I’ve been reading both the second (2011) and third edition (2017) of the book. Nelles outlines an easy to understand historical context for the Boer War. The context in which the Boer War took place – and the conceptual framework within which the war has been represented – are of interest. Knowing about the context is more valuable than being in possession of a grocery list of facts.

That said, what goes into the grocery list of facts regarding such a conflict is also of interest. The choices made, regarding what to include or exclude, will reflect the intended purposes of the associated messaging.

Some years ago, I read a well-written study of which Nelles is a co-author, The River Returns: An Environmental History of the Bow (2009). Nelles has written other books, as well – all of interest and value.

I’ve been reading a library copy of the second edition of A Little History of Canada. Nelles has condensed extensive historical material into an easy to follow format – and it’s clear (from his record as a researcher) that he is solidly grounded in the key historical data.

I’ve bought a copy of the most recent (2017) edition of the book by Nelles. The print size is very small – it’s a real challenge to read the book at any great length. Seeking to cram the most words into the least amount of space portends an exercise, at least in my experience as a reader, in typographical futility.

The pages of the second edition are 6 by 9 inches; the pages of the newer version are about 5 by 7 inches. The text in the third edition appears to be Times New Roman at 8.5 points – very small. I have yet to come across a book for the general reader where the font size is as low as 8.5 points – although I am always checking to see if I can find one. The text in the earlier, second edition appears to be Times New Roman at 10.5 points – look at any page, and you can see it’s very easy to read.

Out of interest, I recently checked the point size in a typical Globe and Mail article. It appears to be 9.0 points – pretty small but the reading is manageable in a newspaper article. As well, I recently began to read a Journal of Fluency Disorders article – where the abstract is in 7.0-point font and the main text is in 8.o-point font. I decided to convert that to a Word file set at Calibri 11.00-point font which is much easier to read.

A novel I’ve recently been reading, Prophet Song (2023) by Paul Lynch, winner of the 2023 Booker Prize, is in Times New Roman 12-point font with generous line spacing. The font size works perfectly in a hardcover book measuring 5.75 by 8.5 inches. Getting the typography right matters hugely. When it’s the right size with optimal spacing the text is easy to read. For the end user – the reader: who else is as important as the reader? – this kind of close attention to detail is highly appreciated.

Concerns about the too-small point size aside, Nelles (2017) is highly informative and well-balanced; the study presents among the best quick surveys of Canadian history I’m aware of.

One possible option, to make it easier to comprehend the text, is to scan the third edition of A Little History of Canada and convert it into something easier to read on a screen or printout – such as, for example, Calibri at 12 points with a line spacing of 1.5.

Persistent regionalism

An article in the Canadian Encyclopedia notes the Boer War “was Canada’s first foreign war.” To participate in such a war, you would first need to have a country; the current post focuses on Canada’s formative years prior to the Boer War.

H.V. Nelles describes how a handful of British colonies in North America coalesced into “a recognizable country” – a home, that is, “to a recognizable people.”

Chapter 3, “Dominion Limited,” in A Little History of Canada, Third Edition (2017) outlines the founding of the country – which, it may be added, took place in the absence of participation from the Indigenous peoples who were living here for thousands of years before Confederation.

On the latter point, I refer to a May 10, 2016 Globe and Mail article, “The roadblock to reconciliation: Canada’s origin story is false,” by Kathleen Mahoney.

Unlike some other countries, such as the United States, Canada did not proceed directly from colony to independence and nationhood. Instead, a gradual process – “something between independence and colonialism” – was chosen, whereby the country gradually expanded the scope of its autonomy within the framework of a modified British empire.

The founders would have preferred to style the country “as a kingdom because they no longer thought of it as a colony.” The British, however, “found this pretentious and absurd.” The term that was chosen was that of a dominion. “With typical condescension the British prime minister thought this silly but harmless. Queen Victoria, however, liked it.”

Chapter 3 refers to “persistent regionalism” as a feature of Canadian history. According to Nelles, such a form of regionalism – in the form of Western alienation, for example – goes back a long ways; such an oft-cited manifestation of regionalism is not something that just turned up one day, out of nowhere.

A system of persistent regionalisms – giving rise to a nation “made up of disparate and quite distinct parts” – is at the heart of at least one version of the origin story of Canada. In this version, Canada has consistently eluded an “unambiguous unity and a singular identity.”

British North America prior to Boer War

In Chapter 3 of A Short History of Canada (2017), Nelles highlights the period between establishment of responsible government (as it was called) in the British North American colonies, and rise of the Liberal Party under Wilfred Laurier, which held power during the Boer War.

I have a particular interest in Nelles’s outline because it provides a structure for further reading from other sources, regarding the power dynamics of Canadian nation-building.

According to Nelles, Canada “was born of imperialism going in reverse.” The coalescence of the British North American colonies appeared to be initiated when Great Britain abandoned mercantilism in the mid-1840s for free trade.

It did so by repealing the Corn Laws in 1846, which had protected British agriculture from foreign competition and gave some imperial preference for colonial producers. Other barriers to free trade were also reduced.

Consequently, “Colonies were no longer considered primarily as captive markets for manufacturers or as preferred producers of commodities.”

In some British quarters, colonies came to be seen as liabilities, because “They were expensive to administer, costly to defend, and they exposed Britain to needless foreign entanglements.”

For the British North American colonies, “Free trade changed everything.”

Britain now “had every reason to encourage colonial self-rule in the hope that self-defence and fiscal self-sufficiency would accompany self-government.” Colonial politicians were ready, as well, “to demand self-government, or responsible government as they called it.”

The election in 1847 in Nova Scotia prompted the colonial governor “to choose his council or cabinet from the political group that commanded a majority in the assembly.” As a result, “for all practical purposes Nova Scotia became self-governing in January 1848.”

In the Canadas (Canada West and Canada East) things did not go as smoothly – there was rioting in the streets – but by 1848 a coalition of forces had achieved a majority in the colonial assembly. The governor, “following the policy established in Nova Scotia, called on them to form a government.”

Responsible government also arrived in Prince Edward Island in 1851 and New Brunswick in 1854. “New governors essentially imposed responsible government on legislatures that somewhat reluctantly assumed the financial burdens of public administration that went along with it. British administrators in Newfoundland experimented with a combined elected and appointed assembly before conceding a fully elected legislature in 1855.”

Vancouver Island and British Columbia

“in the West,” says Nelles, “the two much smaller colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia remained under the direct control of appointed governors, though the Island colony received an elected assembly in 1856. Rupert’s Land in the western interior had no formal government at all save the administration of the Hudson’s Bay Company acting under its Charter from the Crown.”

As noted at a previous post, there is for sure more than one perspective to choose from, when we consider the history of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The story can be treated as something merely picturesque – or it can be treated as the precursor of an accelerating, world-wide exploitation of the endowments of nature, which currently springs forth as a nonstop, accelerating climate crisis.

In Canada East (later Quebec) and Canada West (later Ontario), merchants in Montreal and Toronto were quite concerned about the British abandonment of mercantilism. The merchants, “disoriented by the bewildering reversal of economic policy by Great Britain, issued a manifesto calling for annexation of Canada to the United States. Britain had abandoned its offspring; the United States would not trade with Canada on fair terms.

In distress, the merchants believed that their economic survival depended on Canada joining the United States.” It turned out, however, that “the Americans were not interested in adding territory that would upset the delicate free soil-slave balance. Instead, a political realignment of cultural Conservatives in Canada East and moderate Conservatives in Canada West re-established a measure of parliamentary equilibrium.”

Economic rally

After the policy and market lurches of the late 1840s, “the economy rallied, spurred on by domestic demand, heavy immigration, and a growing continental reorientation of trade.” In 1854, the British government negotiated a Reciprocity Treaty with the United States, “which provided for effective free trade across the border in natural products such as lumber, minerals, wheat, flour, and other agricultural commodities.”

At this time, “railways hastened the growth and development of the colonial economy and governments did everything in their power to assist them.”

The population increased rapidly, thanks primarily to a continued high birth rate supplemented by renewed British immigration “much of it from Ireland as a result of the failure of the potato harvest.”

The “peopling of the colonies” involved a “remarkable fluidity and mobility of a population constantly in motion.” The flow of people moving “through towns, cities, and the countryside seeking better opportunities greatly exceeded the population stock that was resident at any given time.”

Industrialization and immigration, Nelles adds, during this era “introduced new dimensions of religious and ethnic conflict into colonial societies already well endowed with mutual animosities.”

Aside from the brief pursuit of annexation by Montreal and Toronto merchants in 1849, Canadians at this point did not show interest in political independence, remaining “resolutely British in their outlook and attachments.”

“British officials,” Nelles adds, “had to nudge the reluctant colonial governments to think more clearly about their long-term political prospects than they cared to do on their own.”

American Civil War

According to Nelles (2017), “both the British and British North Americans sympathized instinctively with the South” during the American Civil War; in the circumstances, “security became no mere academic matter.”

What the word “instinctively” signifies in such a context remains unclear for me. At any rate, in the shadow of the Civil War, “a movement for political union of the British North American colonies gained momentum.”

“The immediate precipitating factor that propelled events from vague expressions of concern to concrete action was a political crisis in the Canadas in 1864 that forced constitutional reform to the top of the political agenda.”

The British Colonial Office was keen in those years to see the amalgamation of the Maritime colonies, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. This would reduce British obligations “and minimize its defence liabilities.”

The three Maritime governments, while satisfied with remaining separate, “agreed to meet in Charlottetown in the summer of 1864 to begin tentative exploration of the possibilities” of amalgamation.

The threat of war between Great Britain and the United States during the American Civil War prompted the colonies to seriously consider the need to defend themselves. “The British,” says Nelles, “viewed the defence issue as a means of nudging the colonies towards greater co-operation on other common public purposes.”

Apparent British support for the Confederate side during the Civil War “raised the possibility of significant post-war retaliation by the victorious North.” As well, the United States served notice of cancellation of the Reciprocity Treaty. “In this threatening context, the internal politics of the Canadas became unmanageable.” It followed that “conviction hardened that structural reform of some kind was needed to break the deadlock.”

Summer of 1864

Over the summer of 1864, a coalition of parties from the two Canadas

developed a proposal for a federation, which it laid out before the delegates to a conference on Maritime Union in Charlottetown in late August 1864. Following the Maritimers’ enthusiastic response, these general principles were worked up into 72 detailed resolutions, which were debated and approved at a constitutional conference held in Quebec in October.

There was a feeling, according to Nelles, that if a federation was chosen as the preferred route for amalgamation of the colonies, it would need to be highly centralized, as otherwise the conflict that led to the Civil War in the United States, where States’ rights were strong, might be repeated.

Plenty more ground is covered, in the quick historical survey by Nelles which leads up to Confederation in 1867 and the events which followed, before we arrive at the Boer War. In the event a person would like to read Nelles’s brief and informative tour of Canadian history, right up to recent times, they have a choice between the second edition of A Little History of Canada (2011), with its 10.5 point typeface, or they can read the updated third edition, published 2017, with its 8.5 point typeface.

A People’s History of Quebec (2009) by Jacques Lacoursière (Author) and Robin Philpot (Translator), with its 11 point typeface, is also highly recommended – it’s a great survey of Quebec history.

How Boar War was pictured in French Canada and English Canada

I was interested to read the account of the Boer War which appears in A People’s History of Quebec (2009):

Canada was still part of the British Empire and was not master of its own foreign policy. Thus, when Great Britain declared war it automatically declared war for Canada too. The question remained however as to the level of Canada’s participation in wars that were declared by Great Britain. This theoretical question was put to the test in 1899 when London declared war on the Boers in South Africa. Diamond and gold had been discovered in the area and the British were adamant about having control. The British also had grand designs for Africa that included the never completed “Cape to Cairo” railway project so dear to the heart of Cecil Rhodes. While pressure was put on Prime Minister Laurier to send troops to fight alongside the British, pressure from other quarters favoured neutrality since the motives behind the military intervention in South Africa appeared dubious. An order in council dated October 13, 1899 stipulated that the federal government would pay for the equipment and transportation of a contingent of 1000 volunteer troops. When Henri Bourassa, who was Louis-Joseph Papineau’s grandson, demanded that Wilfrid Laurier take into account the opinion of the French Canadians who, for the most part, were opposed to any Canadian participation in the war, the Prime Minister replied: “My dear Henri, the province of Quebec has no opinions, it only has feelings.” The war in South Africa, known as the Boer War, lasted longer than expected, and some 7400 volunteers saw action.

Nelles’s (2017) summary of the Boer War reads:

The Boer War, beginning in 1899, forced these questions onto the political agenda in an inescapable and urgent way. French Canada on the whole identified with the embattled Boers; English Canada supported the British retaliatory invasion. A behind-the-scenes conspiracy of the British Governor General and the British general in command of the Canadian militia to manoeuvre Canada into full participation in the war almost brought down the government. Caught between imperialists on the one side and nationalists in his home province on the other, Laurier adopted the ludicrous compromise of equipping and transporting Canadian volunteers to South Africa, while Britain assumed responsibility for their command and maintenance in the field. As if to tie the bells on this jester’s cap of a policy, the government solemnly declared this should not be considered a precedent for the future. Over 7,000 Canadian volunteers served in South Africa, about 250 of whom perished in the fighting. Not surprisingly, this crisis led to the appointment of a new Governor General and, in due course, a Canadian commanding officer who reported only to the minister of defence. In imperial conferences the British pressed for closer imperial co-ordination of defence policy against which Wilfrid Laurier politely but persistently resisted.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!