In Asylums (1961) Goffman analyzes the inner workings of total institutions

Click here for previous posts about Erving Goffman >

In the preface to Asylums (1961) Erving Goffman remarks (p. 7) regarding his year of field work at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, Washington, D.C., a federal institution of over 7,000 inmates:

- My immediate object in doing field work at St Elizabeth’s was to try to learn about the social world of the hospital inmate, as this world is subjectively experienced by him. I started out in the role of an assistant to the athletic director, when pressed avowed to be a student of recreation and community life, and I passed the day with patients, avoiding sociable contact with the staff and the carrying of a key. I did not sleep in the wards, and the top hospital management knew what my aims were.

Asylums (1961) is a series of interconnected essays

The book is structured as follows:

-

- Preface

- Introduction

- On the Characteristics of Total Institutions

- The Moral Career of the Mental Patient

- The Underlife of a Public Institution: A Study of Ways of Making Out in a Mental Hospital

- The Medical Model and Mental Hospitalization: Some Notes on the Vicissitudes of the Tinkering Trades

Goffman studied everyday life in the old-time mental hospital

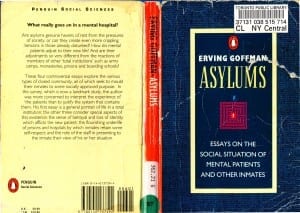

A blurb on the back cover of the 1961 Penguin Books softcover edition of Asylums (1961) outlines the outcome of Goffman’s research project:

“Are asylums genuine havens of rest from the pressures of society, or can they create even more crippling tensions in those already disturbed? How do mental patients adjust to their new life? And are their adjustments so very different from the reactions of members of other total institutions such as army camps, monasteries, prisons and boarding schools?

“These four controversial essays explore the various types of closed community, all of which seek to mould their inmates to some socially approved purpose. In this survey, which is now a landmark study, the author was more concerned to interpret the experience of the patients than to justify the system that contains them.

“His first essay is a general portrait of life in a total institution; the other three consider special aspects of this existence: the sense of betrayal and loss of identity which afflicts the new patient; the flourishing underlife of prisons and hospitals by which inmates retain some self-respect; and the role of the staff in presenting to the inmate their view of his or her situation.”

The copy of the paperback edition of Asylums that I’ve borrowed from the Toronto Public Library provides evidence of the passage of time. The cover has separated from the binding. The pages have yellowed along the edges.

The library copy of this book (see photo on left) is now an artifact. The fact that Goffman continues to be cited, in recent books about many topics, has prompted me to read it now. Several books and online resources, which I’ve found of interest, are also available describing Goffman’s life, personality, and career, and his influence on sociology.

Total institutions

Asylums (1961) has had a lasting impact on many fields of study.

In a footnote (p. 186) in Climate Wars (2012), Harald Welzer highlights Goffman’s dramaturgical perspective on total institutions:

“In his study of psychiatric asylums, Erving Goffman coined the term ‘total institution’ to express the fact that the rules of everyday life outside no longer have validity for their members. For example, they lack the usual accoutrements of identity: they can no longer control how they look to others, since their heads are shaven and they are given a tagged uniform or institutional clothing to wear.

“They are unable to regulate their daily rhythm, are addressed in a standard way, and have little or no contact with the outside world. The special set of rules within the institution is in many respects contrary to the norms prevailing outside. Other examples of total institutions include monasteries, cadet schools and army training camps. See Erving Goffman, Asylums, Garden City, NY, 1961.”

The book is also highlighted in Soldaten (2011).

Entry into a total institution

In the first essay referred to above, Goffman notes that recruits come into a total institution with a conception of themselves made possible by certain stable social arrangements in their home world. Upon entrance, that person is at once stripped of the support provided by these arrangements.

Each person begins a series of abasements, degradations, humiliations, and profanations in which that person’s self is systematically, and often unintentionally, mortified.

In its definition of mortify, the Canadian Oxford Dictionary, Second Edition, speaks of: 1(a) cause (a person) to feel shamed or humiliated; 1(b) wound (a person’s feelings); 2 bring (the body, the flesh, the passions, etc.) into subjection by self-denial or discipline.

Role dispossession

The person entering a total institution begins a radical shift in what Goffman describes as that person’s “moral career,” a career composed of the progressive changes that occur in the beliefs held about one’s self and significant others.

The first curtailment of self that the inmate experiences involves the barrier that is set in place between the inmate and the wider world. Through membership in a total institution, notes Goffman (p. 24), “sequential scheduling of a person’s roles, both in the life cycle and in the repeated daily round” is automatically disrupted, “since the inmate’s separation from the wider world lasts around the clock and may continue for years. Role dispossession therefore occurs.”

Some of the losses of roles “are irrevocable and may be painfully experienced as such. It may not be possible to make up, at a later phase of the life cycle, the time not now spent in educational or job advancement, in courting, or in rearing one’s children” (p. 25).

“The process of entrance” into a total institution, Goffman notes (pp. 25-26), “typically brings other kinds of loss and mortification as well. We very generally find staff employing what are called admission procedures, such as taking a life history, photographing, weighing, fingerprinting, assigning numbers, listing personal possessions for storage, undressing, bathing, disinfecting, haircutting, issuing institutional clothing, instructing as to rules, and assigning to quarters.

“Admission procedures might better be called ‘trimming’ or ‘programming’ because in thus being squared away the new arrival allows himself to be shaped and coded into an object that can be fed into the administrative machinery of the establishment, to be worked on smoothly by routine operations. ”

Brendan Behan enters Walton prison

Goffman notes (pp. 26-27) that in a total institution there is a need to obtain initial cooperativeness from the recruit. In some cases there may be “will-breaking contest: an inmate who shows defiance receives immediate visible punishment, which increases until he openly ‘cries uncle’ and humbles himself.

“An engaging illustration is provided by Brendan Behan in reviewing his contest with two warders upon his admission to Walton prison:

And ‘old up your ‘ead, when I speak to you.’

‘Old up your ‘ead, when Mr Whitbread speaks to you,’ said Mr Holmes.

I looked round at Charlie. His eyes met mine and he quickly lowered them to the ground.

‘What are you looking round at, Behan? Look at me.’

I looked at Mr Whitbread. ‘I am looking at you,’ I said. ‘You are looking at Mr Whitbread – what?’ said Mr Holmes.

‘I am looking at Mr Whitbread.’

Mr Holmes looked gravely at Mr Whitbread, drew back his open hand, and struck me on the face, held me with his other hand and struck me again.

My head spun and burned and pained and I wondered would it happen again. I forgot and felt another smack, and forgot, and another, and moved, and was held by a steadying, almost kindly hand, and another, and my sight was a vision of red and white and pity-coloured flashes.

‘You are looking at Mr Whitbread – what, Behan?’

I gulped and got together my voice and tried again till I got it out.

‘I, sir, please, sir, I am looking at you, I mean, I am looking at Mr Whitbread, sir.'”

[End of excerpt]

The reference is: Brendan Behan (1958), p. 40.

Lakeshore Hospital Grounds

Goffman’s study was one of a number of influences on the deinstitutionalization movement of the 1960s. An article Bernard E. Harcourt entitled “Reducing mass incarceration: Lessons from the deinstitutionalization of mental hospitals in the 1960s” offers an overview of this topic.

The reference for this paper is: University of Chicago – Department of Political Science; University of Chicago – Law School, January 26, 2011: U of Chicago Law & Economics, Olin Working Paper No. 542; U of Chicago, Public Law Working Paper No. 335.

A good overview of how the ideas in Asylums have fared in the years since its publication is available in Gregory W. H. Smith’s study of Goffman’s life.

Goffman’s overview is of relevance with regard to the Lakeshore Hospital Grounds in New Toronto, close to Long Branch (in Toronto not New Jersey) where I live. The topic of incarceration is of relevance as well.

Many perspectives are available regarding the nature of mental illness and mental health

Goffman offers a valuable symbolic-interactionist perspective on issues related to mental health.

Additional perspectives come to mind.

A January 2013 New York Times article, “Successful and Schizophrenic,” is of interest.

As well, the role that early childhood experience plays with regard to adult mental health is addressed in a January 2013 Globe and Mail article.

A Feb. 28, 2013 CBC report refers to research suggesting genetic links among five mental disorders.

A May 10, 2013 series published in The Lancet addresses bipolar disorder.

A May 23, 2013 Globe and Mail article by Wency Leung highlights the worldview of a sociopath. The article notes that the terms sociopath and psychopath are often used interchangeably by lay persons and there’s a lack of consensus on the differences.

“Those who live among us [as sociopaths],” the article notes, “are believed to thrive in leadership positions in the corporate world and in politics, due to their ruthlessness, charm and penchant for taking risks, but they are also difficult to identify.”

An article in the Spring 2013 issue of Maisonneuve highlights a coroner’s inquest regarding what is described as a Canadian opioid-abuse crisis. A June 12, 2013 Toronto Star article highlights the marketing of opioids in Canada.

A May 2013 article in The Walrus and a May 18, 2013 Toronto Star article each addresses controversies associated with the task of defining mental illness.

April and May 2013 New Yorker has two well-written articles regarding the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

The May 16, 2013 New Yorker also addresses this topic in a cogent and well-written article, which begins with the following sentence:

“When Thomas Insel, the director of the National Institute of Mental Health, came out swinging with his critiques of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a couple of weeks ago, longtime critics of psychiatry were shocked and gratified.”

Further into the article one reads: “Looking for the neurochemistry of mental disorders that don’t necessarily exist has turned out to be as futile as using a map of the moon to get around Manhattan.”

An April 9, 2013 New Yorker article similarly addresses the topic of how mental illness is defined.

A July 24, 2014 New Yorker article notes that prescription medications now kill more people than heroin and cocaine combined. The article is entitled: “Who’s afraid of Zohydro?”

Of two minds (2000)

Also of relevance, with regard to debates related to mental illness, is Of two minds: The growing disorder of American psychiatry (2000) by the American anthropologist T. M. Luhrman. The book is discussed at a separate blog post.

Also of interest is an article by Luhrman in The Wilson Quarterly, Summer 2012, entitled “Beyond the brain.”

The subtitle for the latter article reads:

“In the 1990s, scientists declared that schizophrenia and other psychiatric illnesses were pure brain disorders that would eventually yield to drugs. Now they are recognizing that social factors are among the causes, and must be part of the cure.”

Doors Open at Humber College

I enjoyed a May 25, 2013 Doors Open tour of the Humber College campus. We had a tour of some of the tunnels that were built to connect the buildings at the Lakeshore Hospital Grounds.

We also learned of where electroshock treatments and frontal lobotomies were conducted at the facility before it was closed. The latter topic accounts for my interest in a May 23, 2013 review in the London Review of Books concerning the nature of memory.

Updates

An Oct. 5, 2013 New York Times article regarding how social power differentials play out in social interactions ties in well with Erving Goffman’s analysis of everyday life from a social interactionist perspective.

A March 26, 2015 New York Times article is entitled: “Inside America’s Toughest Federal Prison: For years, conditions inside the United States’ only federal supermax facility were largely a mystery. But a landmark lawsuit is finally revealing the harsh world within.”

A March 26, 2015 New York Times article is entitled: “‘Shrinks,’ by Jeffrey A. Lieberman with Ogi Ogas.”

A blurb for Shrinks (2015) at the Toronto Public Library website notes:

“The fascinating story of psychiatry’s origins, demise, and redemption, by the former President of the American Psychiatric Association.

“Psychiatry has come a long way since the days of chaining ‘lunatics’ in cold cells and parading them as freakish marvels before a gaping public. But, as Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, reveals in his extraordinary and eye-opening book, the path to legitimacy for “the black sheep of medicine” has been anything but smooth.

“In Shrinks, Dr. Lieberman traces the field from its birth as a mystic pseudo-science through its adolescence as a cult of ‘shrinks’ to its late blooming maturity – beginning after World War II – as a science-driven profession that saves lives. With fascinating case studies and portraits of the luminaries of the field – from Sigmund Freud to Eric Kandel – Shrinks is a gripping and illuminating read, and an urgent call-to-arms to dispel the stigma of mental illnesses by treating them as diseases rather than unfortunate states of mind.”

[End of text]

A Feb. 7, 2016 Guardian article is entitled: “‘My family resisted the Nazis’: why director had to film Alone in Berlin.”

An Aug. 15, 2016 Guardian article is entitled: “Joseph Goebbels’ 105-year-old secretary: ‘No one believes me now, but I knew nothing’: Brunhilde Pomsel worked at the heart of the Nazis’ propaganda machine. As a film about her life is released, she discusses her lack of remorse and the private side of her monstrous boss.”

Hello,

I’ve been reading a collection of essays, interviews, and lectures of Michel Foucault, and he mentions Asylums in Truth and Juridical Forms. He brings up the idea of ‘total institutions’ as he details the evolution of surveillance societies. All of this is very intriguing as we see how much reach law enforcement agencies now have. Do you have any recommendations for any other literature that delves into these types of issues? I’m also in the process of researching doctoral programs that would explore the foundations and growth of human societies and individuals. Any recommendations on that end would be greatly appreciated.

Thanks,

TJH

You’ve chosen an interesting and relevant area to focus upon – with regard to the range of issues that are at play, and with regard to doctoral programs.

Erving Goffman’s daughter Alice Goffman may be a good person to contact regarding the range of relevant doctoral programs:

http://preservedstories.com/2014/05/06/alice-goffmans-on-the-run-studies-policing-in-a-poor-urban-neighborhood-new-york-times-april-29-2014/

A key part of the narrative, with regard to “total institutions,” concerns how we as human beings go about making sense of things. In that regard, you may wish to contact Daniel Kahan, a Yale law professor:

http://www.culturalcognition.net/kahan/

As well, “total institutions” are concerned with the channelling of perceptual processes associated with everyday social intelligence. In that regard, Daniel Goleman’s wide range of published work is likely to contain references to researchers and research institutions that may be of relevance to you:

http://hbr.org/2008/09/social-intelligence-and-the-biology-of-leadership/ar/1

Some posts related to military and cultural history at own website may also warrant a look, from the perspective of academic contacts:

http://preservedstories.com/category/military-history/

Among posts that come to mind, by way of example, are:

http://preservedstories.com/2012/11/24/soldaten-on-fighting-killing-and-dying-the-secret-world-war-ii-transcripts-of-german-pows-neitzel-and-welzer-2011/

http://preservedstories.com/2013/08/26/war-is-work-that-soldiers-do-evil-men-2013/

http://preservedstories.com/2012/08/27/the-impact-of-postmodernity-on-historical-practice/

http://preservedstories.com/2013/08/06/the-drug-wars-in-america-1940-1973-kathleen-j-frydl-2013/

http://preservedstories.com/2013/06/06/the-true-intrepid-sir-william-stephenson-and-the-unknown-agents-2001/

http://preservedstories.com/2013/12/31/the-meaning-of-neoliberalism-has-changed-dramatically-since-its-origin-in-interwar-germany/

http://preservedstories.com/2013/12/25/status-update-celebrity-publicity-and-branding-in-the-social-media-age-alice-e-marwick-2013/

http://preservedstories.com/2014/07/21/virtual-unreality-just-because-the-internet-told-you-how-do-you-know-its-true-2014/

Worth keeping in mind, as you proceed with your studies, is the argument that academic institutions reward specialization, and specialists are invariably at risk of missing the larger problem:

http://www.newyorker.com/tech/elements/spare-the-rod-school-the-child