In Stratford as in Toronto and Mississauga, people have worked together many years, in order to save cherished historical buildings and neighbourhoods from destruction

It’s now been four months since we moved to Stratford.

For the previous three months, after we sold our house in Toronto and before we moved to Stratford, we had rented places across Ontario and Europe. We sold our house in southern Etobicoke in July 2018 and moved to Stratford in October 2018.

Cultures of land-use decision making

As newcomers, we’ve been getting to know Stratford on many levels, including as observers of the local history of land-use decision making. How cultures of decision making, related to how land gets used, originate and evolve over time is of much interest to me.

My involvement with local history dates back to October 2010, when I learned that a local school, close to where we were living at the time, was about to be sold.

Through a letter-writing campaign, focusing on the heritage value of the archaeological and historical features of the school grounds, of the property in question, local residents were able to persuade provincial decision makers to release $5.2-million to enable one school board to sell the property to another board. As a result, the school remains in public hands.

That particular effort, involving community self-organizing at the local level, gave rise to my current interest in local history.

In recent years, I’ve been studying the evolution and differentiation of land-use cultures, going back many years, in waterfront neighbourhoods in Mississauga and Toronto.

As a newcomer, at a stage of getting to know a city, during which first impressions, and fresh insights, can play a leading role, many features of built form and land use in Stratford have at once caught my attention.

Case Study 1: Saving Union Station

There are some features, specifically in relation to land-use decision making, that are similar in Stratford and Toronto, despite the vast differences, in size and density, between the two cities. There are key differences, between the two municipalities, as well, but in this post I’ll focus on similarities.

One of the shared features, of land-use history in both cities, concerns past encounters with dramatic close calls. I speak, in this context, of emerging situations where all that stood in the way of disaster, as viewed from the vantage point of heritage preservation, was the strategically focused opposition of concerned citizens.

The first near-disaster that comes to mind concerns a plan afoot, in the 1970s or thereabouts, to demolish Toronto’s historic Union Station. I came across this story just recently, in a 2010 Urban History Review article entitled: “American Expatriates and the Building of Alternative Social Space in Toronto, 1965–1977.”

The article refers (p. 15) to the involvement, in the Save Union Station project, of a young war resister from the United States:

Rick Bébout, a nineteen-year-old war resister who came to Toronto from Massachusetts, was able to find social causes and activities that inspired him and brought him together with like-minded individuals. Landing a job at the Book Cellar, a store in the city’s Yorkville neighbourhood, helped integrate Bébout to life in Toronto. Through co-workers and regular [Book Cellar] customers who befriended him, Bébout became involved in efforts to preserve Toronto’s historic Union Station from the wrecker’s ball. With the help of Rochdale College veteran Pam Berton, the daughter of prominent Canadian journalist Pierre Berton, Bébout edited The Open Gate: Toronto Union Station, a history of Union Station, and was at the centre of the successful battle to preserve the building. [59]

Footnote 59 reads:

[59] Rick Bébout, interview by the author, tape recording, Toronto, 2 September 1998. Richard Bébout, ed. The Open Gate: Toronto Union Station (Toronto: Martin, 1972). Prominent Canadian journalist Pierre Berton wrote a preface to the collection, giving the book a considerable degree of attention.

[End]

Case Study 2: Cancellation of Spadina Expressway

The second near-disaster concerns the plan to build the Spadina Expressway, which would have destroyed large swathes of historic Toronto neighbourhoods.

The previously cited Urban History Review article notes (p. 40), with regard to the Spadina Expressway, that:

In addition to covering movement politics in the United States, the escalation of the Vietnam War, campus unrest, and the activities of groups like the Black Panthers, Guerilla [Toronto underground newspaper] supported more local efforts, including the Stop Spadina campaign, which scuttled plans to build an expressway along Spadina Avenue through a number of inner-city neighbourhoods. [114]

[To the above-noted excerpt, I’ve added a link to previous posts about the Vietnam War; in the footnote that follows below, as in the previous footnote, I’ve added links to the books that are cited.]

Footnote 114 reads:

[114] Dee Charles Knight, “Amnesty . . . Again,” Guerilla, 2 February 1972, 18–19; Ron Verzuh, Underground Times: Canada’s Flower Child Revolutionaries (Toronto: Deneau, 1989), 148–149. On the Spadina Expressway debate, see Jon Caufield, The Tiny Perfect Mayor (Toronto: Lorimer, 1974); Daryl Newbury, Stop Spadina: Citizens against an Expressway (Mississauga: Common Act, 1989).

[End]

These two instances – saving of Union Station and scuttling of the Spadina Expressway – are among key events, in my view, in the history of land-use decision making in Toronto. With regard to comparable events in Stratford, two additional stories come to mind.

Avon River. View from north riverbank looking east. This stretch of water is also known as Lake Victoria, which has been created by the R.T. Orr Dam. Without the dam, the river would revert to a small creek, as noted in Stratford: Its History and Its Festival (1999), p. 74. Jaan Pill photo

Case Study 3: 1912 referendum scuttles railway along Avon River

Stratford has an extensive park, in place for many years, along the Avon (rhymes with “anon”) River, which runs through the city. At one point, in the early 1900s, a plan was afoot to build a railway along the river, through the city’s historic park.

There were arguments for and against such a railway. The matter came to a vote, in a 1912 referendum among Stratford residents. A majority voted against the railway and the idea was dropped. As a result, the park along the river remains a celebrated feature of life in Stratford, to this day.

Case Study 4: Concerned citizens save City Hall from demolition

A second story from Stratford dates from the 1960s. Stratford has an impressive City Hall, dating back many years, with noteworthy architectural features.

If you’ve ever been to Stratford, the image of this building is among the things that will likely stay in mind, for you. In the 1960s a plan was afoot to demolish it. The demolition did not proceed, because citizens convinced decision makers to preserve the City Hall, for the ongoing enjoyment of current and future generations.

Stratford: Its History and Its Festival (1999)

If you want a succinct, evidence-based overview of Stratford history, including brief accounts of Case Studies 3 and 4, an excellent resource is entitled: Stratford: Its History and Its Festival (1999) by Carolynn Bart-Riedstra and Lutzen H. Riedstra.

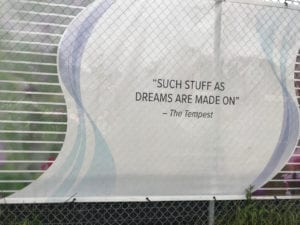

Detail at perimeter of Tom Patterson Theatre Centre construction site by Avon River in Stratford. Jaan Pill photo

The authors were, at the time the book was published, archivists at the Stratford-Perth Archives. They had, as well, by that time in their careers conducted walking tours in Stratford, and had written articles for The Beacon Herald newspaper. This combination of capabilities – namely, archival research along with experience in reaching out to public audiences – is readily evident, when you read this valuable, engaging overview of Stratford’s history.

I was interested to read a quote (p. 58) in the book, in which Tyrone Guthrie speaks about the characteristics of arts-oriented committees he had encountered in the past, and which, in his view, stood in welcome contrast to the composition of the committee he met in Stratford in July 1952.

His comments appear typical of stereotyping – with regard, say, to the roles of women, men, and the elderly – that was predominant in the 1950s and that remains in place to one degree or another even now. Stereotypes, in the dramatic arts as with regard to how the members of committees are viewed, remain a key ingredient, in the social construction of our everyday realities.

Detail at perimeter of Tom Patterson Theatre Centre construction site by Avon River in Stratford. The link in the photo can be accessed here: stratfordfestival.ca/TPT. Jaan Pill photo

This point aside, the fact Guthrie had a free rein to put into place his concept, developed over many years, of how to design a stage suitable for Shakespeare’s plays, and how to organize a major, top-quality dramatic production, clearly played a key role in establishing Stratford as a world famous Shakespearean centre.

A Feb. 8, 2019 Beacon Herald article, of interest with regard to Guthrie’s legacy, is entitled: “Stratford company making documentary on legacy of Sir Tyrone Guthrie: A Stratford production company is planning on shooting a documentary next year on the impact Stratford’s theatrical development had on theatre around the world.”

An excerpt, to which I have added links, reads:

The idea for the documentary was inspired by the the National Film Board’s 1954, Oscar-nominated documentary, The Stratford Adventure, which shared the against-all-odds story of how a small town in rural Ontario was taking on the theatre world with a summer Shakespeare festival under the artistic direction of Guthrie, an English theatre director.

“In 1953, as first artistic director of the Stratford Festival, Tyrone Guthrie pioneered a revolutionary new way of staging Shakespeare and other classic dramas,” said current artistic director Antoni Cimolino in a press release.

“The innovative thrust stage that he conceived with designer Tanya Moiseiwitsch has been a defining feature of the festival for more than 65 years and has inspired such other venues as the Guthrie Theater, the Chichester Festival Theatre, and Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater. Guthrie’s experiment in Stratford sowed the seeds for a new approach to classical theatre around the world.”

[End]

National Film Board’s “reconstruction of reality”

The reference, in the above-noted excerpt, to the National Film Board, and to the NFB short (39 minutes), The Stratford Adventure (1954), brings to mind a passage in an earlier post, which reflects upon the sociologist Erving Goffman’s connection to the NFB:

Smith notes (pp. 14-15) that “Goffman’s contribution to the war effort was to work for an agency [that is, the NFB] then heavily involved in the production of propaganda films. At that time the noted Scottish documentary filmmaker, John Grierson (1898-1972) directed the Board.

“While Goffman’s duties were mostly low-level and routine (boxing films for dispatch and preparing cuttings files from magazines), he could not have avoided exposure to discussions about filmic practices for decomposing ordinary life into elements that could then be reconstructed as a representation of reality [Y. Winkin, ed., Erving Goffman: Les moments et leurs hommes (1988), pp. 20-21].”

[End]

By way of a brief film review:

Detail at perimeter of Tom Patterson Theatre Centre construction site by Avon River in Stratford. Jaan Pill photo

The above-noted NFB film about the launch of the Stratford Festival, while characteristically – or, one could say, suitably – portentous, is nonetheless possessed of a serviceable storyline. The film’s voiceover script makes good use, on occasion, of quotations from Shakespeare’s plays. When lines from Shakespeare are delivered during the depicted rehearsals, they start to come to life.

It’s of much interest to view Tyrone Guthrie in performance, in the film, in his role as theatre director. He is firmly in command, and demonstrates mastery of his craft.

It’s wonderful to see the work of designer Tanya Moiseiwitsch highlighted. Her contribution was a key factor in the successful launch of Stratford’s Shakespearean festival. Among other key contributors, as Guthrie notes in A Life in the Theatre (1959), were Cecile Clarke, production assistant to Guthrie; Ray Diffen, a leading theatrical cutter; and Jacqueline Cundall, who oversaw accessories and properties.

My favourite line from the film (from a discussion about breath control): “Can you do six lines of Shakespeare on one breath?” The speaker is Alex Guinness. He has a strong screen presence. The scene where he dons sunglasses and saunters off is memorable.

The music in the opening segments has a predictably treacly quality, as can be expected in this genre of filmmaking. However, the trumpet notes and sound effects during the swordplay and general mayhem, in the final staging of Richard III, on opening night, work just right.

The ubiquity of cigarette and pipe smoke, in every imaginable indoor and outdoor setting, is among the details, related to everyday life in the 1950s, that the film has captured well. The film also captures the ubiquity of bicycles as a standard and much enjoyed means of transportation in Stratford, in those years.

The film reminds me, as well, of the Film Board’s heavy (and necessary) involvement with production of propaganda films during the Second World War. The history of the NFB is of interest, in its own right. Its history is evident, in my experience from earlier years as a film reviewer (in the 1970s), in each of its productions or co-productions, no matter what the topic at hand may be.

I note also that the film features heritage houses, characteristic of many Stratford streetscapes. I am pleased that, by and large, the same houses continue to grace the same neighbourhoods these many years later, and are generally all in good repair.

At a previous post, I’ve discussed changes that have occurred, over the years, in the Film Board’s approach to topics related to land-use decision making at Regent Park in Toronto:

Stratford and Mississauga have achieved noteworthy success in land-use decision making

Cultures of land-use decision making have evolved in ways in some respects strikingly similar, and in other ways vastly different, in Stratford, Mississauga, and Toronto.

Stratford and Mississauga share similarities, for example, given that each city has given rise, in the evolution of its land-used planning journey, to key, community-driven visionary projects, initiated at the grassroots level.

One such project was initiated by Tom Patterson, a resident of Stratford; another was initiated by Jim Tovey, a resident of Mississauga. Their stories are highlighted at a previous post entitled:

Such initiatives stand in strong contrast to predominantly top-down projects of a kind highlighted in previous posts regarding the history of land-use decision making, in settings such as, for example, Saint John, New Brunswick.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!