My interest in colonial and military history began with a study of local history in Toronto

At a previous post, I have shared a comment about the study of history.

I will repeat the discussion at the current post, in the process adding a few details and photos, in order to bring attention to the comment.

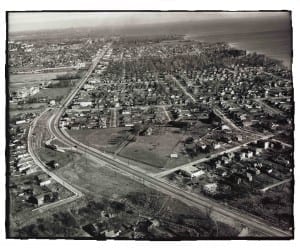

Aerial view looking east along Lake Shore Blvd West from near Long Branch Loop, Ontario Archives Acc 16215, ES1-814, Northway Gestalt Collection. The original Colonel Samuel Smith house (a log cabin to which extensions and siding were added over the years) is visible at the centre of the photo. Click on photo to enlarge it.

I began my own study of history around 2011, when I became interested in the backstory of the Toronto neighbourhood of Long Branch where we lived from 1997 to 2018.

A few but not many details are available in archival and historical records, regarding the first European settler in Long Branch, a British colonel named Samuel Smith.

In 1797, the colonel built a log cabin in a forest clearing located at what is now a schoolyard in Long Branch, a one-minute walk from the house where we lived for 21 years until 2018, after which we moved to Stratford.

The colonel in those days was the sole settler landowner in what is now Long Branch. His property, covered in forests, actually extended beyond the current boundaries of the neighbourhood.

An Indigenous trail through the forests, aligned with the shoreline of Lake Ontario, became the basis of the the route that Lake Shore Blvd. West now follows as it proceeds across South Etobicoke. The trail also became the basis of the route that Lakeshore Road follows in Mississauga.

One of his contemporaries, a Scottish author named Robert Gourlay, who had visited the colonel’s property on a horseback journey through the wilderness (by which I mean untrammelled nature), complained (and this is a paraphrase) that Colonel Smith wasn’t doing enough to quickly bring prosperity to his lands.

One of the things the colonel did get around to doing was allowing people to cut down trees on his land, to be sold as timber. The cutting down of large portions of the great forests of Etobicoke Township, starting in Colonel Smith’s time and continuing after he had passed away in 1826, resulted in serious flooding problems along Etobicoke Creek beginning about 1850.

View of school grounds, looking north toward Lake Shore Blvd. West, at former Parkview School. The school was subsequently renamed St. Josaphat Catholic School; its current name is l’École élémentaire Micheline-Saint-Cyr. Click on photo to enlarge it. Jaan Pill photo

As noted at a post about the history of Long Branch, the colonel’s house, located northeast of the mouth of Etobicoke Creek, was in continuous use for about 152 years from 1797 until around 1949, before the house was demolished in 1955.

As noted at another previous post, the land on which the house was built had become a farmstead in the countryside. With the passage of time the farmstead became surrounded by a growing city, as the remnants of the post-forest rural landscape disappeared.

Eventually the house and farmstead disappeared as well, when Parkview School was built on this land (which like all land in the area is now highly valued as real estate) during the 1950s postwar baby boom.

I had the good fortune while we lived in Long Branch to interview residents, then in their eighties and nineties, who had first-hand recollections of the old farmstead including its apple orchard, horses, and farm buildings.

Back view (facing south) of Colonel Samuel Smith farmstead house, located at what are now the school grounds of the former Parkview School. Originally a log cabin, built in 1797, the house had siding and extensions added to it over the years. Photo © Betty Farenick and family

That’s how I was able to acquire one of the images, one of several such scans of photos that I’ve acquired in recent years of the old Samuel Smith farmstead house, that appears at the current post.

Photos of the house are also available at the archives at Montgomery’s Inn, but the captions at the photos feature the misleading claim that the house was torn down in 1952, a claim that is not supported by the available evidence, as I will note below.

The site of the house was thoroughly razed – cleared out by a bulldozer – to the extent that little archaeological evidence of the existence of the building remains.

Dena Doroszenko, an archaeologist, did a preliminary archaeological dig at the Parkview School site in 1984. She has suggested that the artifacts from the building may have ended up in the embankment that was built up in an area of the school grounds located immediately to the north of a baseball backstop that used to be in place at the school grounds until recently.

No-one had stuck the colonel on a pedestal as a historical figure, which is fortunate, as otherwise I would not have developed a curiosity about his life. Once a figure in history is placed upon a pedestal, I for one have a diminished interest in the matter.

As a consequence of my fortunate state of ignorance about an obscure British colonel, I began reading about British colonial history and world military history, so that I could get a sense of the colonel’s life and times.

The first book I read about the British empire presented what I subsequently came to see as a one-sided celebration of British colonial history. To enjoy reading such books, you have to have a taste for them. My tastes are not in such a category.

With further reading, I arrived at what I like to think is a more nuanced, more balanced view of British history.

View of l’École élémentaire Micheline-Saint-Cyr (formerly Parkview School), photographed from top of Aquaview Condominiums, November 2012. Click on photo to enlarge it. Jaan Pill photo

History of police service in Long Branch

Around the same time that I began to read about British history, I also began to educate myself about the history of the police service in Long Branch.

I thought it would be an interesting topic to study. I first began to think about it when I attended a talk at a local historical society (currently defunct) where an anecdote was shared about long-ago policing in Long Branch.

I learned a lot by interviewing old-time Long Branch residents. They told me about a fabled, much-admired police chief of the old Village of Long Branch.

I also began to read about the history of police services in Toronto, then moved on to the history of police services in Ontario, across Canada, and elsewhere.

What I learned led me in turn to reading about colonial and military history, in Canada and in other countries around the world.

Policing can turn out to be hard work performed under arduous conditions which can, at times, give rise to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. In this context, an Aug. 15, 2019 Associated Press article is entitled: “Police departments confront ‘epidemic’ in officer suicides.” An Aug. 18, 2019 Associated Press article is entitled: “French police suicide rate climbs, French govt is flummoxed.”

My interest in the history of policing, along with wanting to know more about the life of Colonel Samuel Smith, led me to learn as much as I could about colonial and military history.

A common element in all such history is military strategy – that is, how to most effectively proceed with the organized violence that warfare (including hybrid warfare) entails.

During the past eight years of reading, I’ve achieved a slightly diminished level of ignorance regarding history.

In the wider society, the view that people in general have regarding history has broadened. By way of example, there is now a greater interest in study of Indigenous perspectives regarding history.

Verification of information about local history keeps the story straight

With regard to local history everywhere, I’ve learned that it’s important to verify and corroborate information – regarding dates when events have occurred and other details of storytelling.

As I’ve noted in a post about the history of Long Branch, for example, some online sources, along with a set of archival photos at Montgomery’s Inn, claim the Samuel Smith house was torn down in 1952 whereas newspaper records provide evidence that it was actually torn down in 1955.

Similarly, the Long Branch Hotel burned down in 1958, as eyewitness accounts and archival records indicate, yet we still encounter claims in accounts of local history, including at an entry that I’ve come across at a library book, which assert the event occurred in 1954.

Does it matter what year some event in local history actually happened? It matters to me, as a person involved with journalism for the past half-century.

The backstory here is that some local historians are aware of how to go about verifying and corroborating information, and some do not have a clue meaning that some uncorroborated stories may be repeated endlessly as the years go by.

Out of hundreds of non-fiction books, a small number have really hit home for me

It’s my view that no-one is in a position to explain everything there is to explain.

In the process of reading, I have developed some degree of understanding of how historians and other writers (such as anthropologists and political scientists) go about their work.

Of particular interest to me is how well a given writer is acquainted with archival and secondary sources, in a given subject area, and how well a study is organized within the space that’s available in a typical book-length study.

As well, the style of writing matters – I like coherence, clarity, and a sense of organization.

It’s also most valuable if a text gives rise to a sense of engagement on the part of the reader. A text has to be sufficiently engaging, so that the reader is convinced to read it. In a sense, a text has to sell itself.

At the same time, however, I prefer the absence of a strong emphasis on directing how a reader is supposed to respond emotionally to the story, characters, and situations that a writer presents.

All these points aside, style of writing matters less than content. Impressive style sometimes goes with mediocre content; conversely, a text delivered in a plodding, pedantic style of writing may nonetheless be worth reading as the content may be of tremendous value.

Marketing and public relations writing when done well, as it often is, is beautifully written. Of necessity, it involves a characteristic, smoothly flowing style of writing. Such writing has its place. It’s there to sell a message. For many years as a volunteer I was involved with writing of news releases; such writing can serve a valuable purpose.

The mixing of history writing with marketing or public relations, however – or with promulgation of ideology – does not appeal to me.

People who write valuable things about history

I have an interest in the work of:

- Academic writers connected with university departments in various disciplines;

- Writers working within other frameworks such as the Brookings Institution connected with university departments as well as varied levels of government; and

- Writers working outside of university settings such as Jane Jacobs, who has written extensively about history.

Bibliographical sources related to Colonel Smith and his times

A subsequent post is entitled:

Finding Cleo – CBC Podcast

As I have been working on recent posts, I have been listening, on CBC The Current, to the CBC podcast, Finding Cleo, hosted by Connie Walker.

I’m looking foreword to listening to the entire podcast, which can be accessed at the link in the previous sentence; a YouTube link about the podcast follows below:

Col. Sam Bois Smith was born in Hempstead Village, New York on December 27th, 1756, the son of Scottish immigrants, James Smith and Isabella Clarke. In 1771 between the age of 20 and 21 he joined the Queens Rangers and fought in the American Revolutionary War. He surrendered to the Americans after the Battle of Yorktown.

He then moved to the new colony of New Brunswick and went to England in 1784. Becoming a captain he was sent to Niagara in 1791 as a Loyalist British Army Officer. In 1801, at about the age of 45 and before retiring to the thousand acres of land he bought in Etobicoke, which were mainly trees back then, he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel of his regiment.

In 1817, he was appointed the administrator of Upper Canada in the absence of the Lieutenant Governor from 11 June, 1817 to 13 August 1818 and again from 8 March 1820 to 30 June 1820. He was considered a weak official and as John Strahan, who he had sold some land to, feeble, inept and talentless. He retired from the Executive council in October 1825 and died a year later on 20 October, 1826 at age 69 leaving behind a wife and nine children.

Hi Bob,

Good to read your comment. It’s good to have a discussion. At a subsequent post based on an entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, I’ve added more details from the historical record.

Your overview sounds like something based on material I’ve seen online. You do not provide a source. A source for all such quotes is essential, in my view.

As you know, I tend to steer clear of Wikipedia.

Samuel Bois Smith as I understand is the name of Samuel Smith’s son. The two names get mixed up from time to time and then the mixup is repeated. I’ve seen the name Samuel Bois Smith turning up at the Toronto Public Library website, assuming I am correct in my recollection. I will have to check.

Samuel Smith didn’t buy the land; instead, it was a typical British colonial land grant that he received. In the process the original Indigenous inhabitants of the land were pushed aside in keeping with standard colonial practice.

In worldwide colonial history the Indigenous inhabitants of such lands succumbed to disease arriving with settler society, were pushed aside to marginal lands, or were killed – including as the intended result of death by starvation.

Settler societies also generally sought to destroy Indigenous cultures, cultural practices, belief systems, and languages through a process of coercive assimilation – through a process, that is, of cultural genocide.

As has also been standard practice, settler histories of the kind taught in schools have until recent times tended to ignore or gloss over such details.

Retired military men such as the colonel received land grants west of York (now Toronto) so that York could be defended in the event of an American overland attack from the west directed at York. Retired officers received huge land grants; lower ranks received smaller ones. As it turned out, during the War of 1812 such an attack and subsequent occupation of York did occur but the American forces arrived via Lake Ontario instead of overland.

As I note in a subsequent post, it may be the case that the colonel was born in 1760 not 1756.

In her archaeological report of 1984, Dena Doroszenko offers evidence suggesting that 1760 is the more likely year of birth. The latter archaeological report was on the occasion of the preliminary dig that was conducted at the site in Long Branch where the colonel had built his log cabin.

A previous post provides background about the preliminary dig: Whatever happened to the Colonel Smith homestead artifacts found in 1984?

Best,

Jaan