Dramatic changes along Exmoor Drive by the GO Station bring to mind the previous history of Long Branch

Image from Oct. 21, 2024 Toronto Star article; the caption reads: “Exmoor Drive in Long Branch used to be comprised of nine ‘strawberry box’ bungalows from around the Second World War. Today, only three remain and one just went up for sale.” Photo source: R.J. Johnston/Toronto Star

Updates: I uploaded this post on Oct. 23, 2024. Since then, I’ve added more email comments from Garry Burke, who lived at Exmoor Drive in the 1950s, after moving from the Long Branch Army Camp. With his permission, I’ve added to his earlier comments. In the Comments section below, I’ve added links to books and articles. Such additions stem from the realization that when land is viewed strictly as a ‘financialized’ asset, as is evident from the Toronto Star article, the worldwide housing crisis is the inevitable outcome. An Oct. 29, 2024 The Conversation article is of relevance regarding this topic as are the following articles. A Nov. 1, 2024 The Tyee article about the Canadian housing crisis outlines suggested solutions. A Nov. 3, 2024 CTV article from The Canadian Press echoes possible solutions highlighted in the Tyee article. As well, a Nov. 3, 2024 CBC article describes the clearing of housing from the Etobicoke Creek floodplain at the Lake Ontario shoreline following Hurricane Hazel. A Nov. 18, 2024 CBC article also addresses flooding. On a topic related to housing, an Oct. 2, 2024 The Conversation article focuses on the clearing of encampments as does a Nov. 25, 2024 BBC article and a Dec. 4, 2024 CBC article.

Regarding suggested solutions, the industry of ‘urban solutions’ may not be helpful for cities, as a Nov. 13, 2024 The Tyee article underlines. Also regarding solutions, I’ve been reading Question Authority (2024), about how to make the world a better place. A worthwhile, philosophical read.

[End of updates]

*

I was interested to read an article by Diana Zlamislic, Housing Reporter, in the Oct. 21, 2024 Toronto Star, entitled: “How property flippers transformed an entire street of Toronto ‘strawberry box’ homes.” Part of a series about dramatically rising house prices, the article describes what used to be “nine squat, single-storey homes on a short stretch of road with a front-row view of a bustling transit loop.”

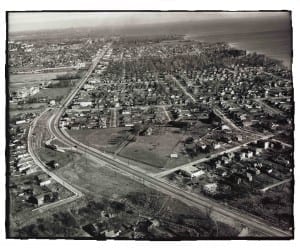

Aerial view from November 1949 looking east along Lake Shore Blvd West from near Long Branch Loop, Ontario Archives Acc 16215, ES1-814, Northway Gestalt Collection. On the left is Exmoor Drive, which extended further to the east in this 1949 view, than it does now, as noted at a post entitled: Life at the Long Branch Army Camp, long, long ago! – Garry Burke shares additional comments. Click on image to enlarge it.

Exmoor Drive neighbourhood

The first photo at this post features a view from the Toronto Star of Exmoor Drive looking north from the Long Branch TTC loop.

A previous post features an archival aerial photo showing, at the left of the image, how Exmoor Drive appeared in 1949. Before the construction of the current termination of Brown’s Line at Lake Shore Blvd. West, Exmoor Drive terminated directly at Brown’s Line. As well, the GO Station parking lot now covers the ground, where Exmoor Drive previously extended further toward the west.

Another previous post features a two-minute video in which Bill Rawson, who used to own a used furniture store on Lake Shore Blvd. West opposite the Long Branch Public Library, speaks about life in the 1950s in Long Branch including where the GO Station is now located. He describes two site visits we could make in Long Branch. These would enable Bill to share his first-hand acquaintance with the history of Long Branch dating back to the 1940s and 1950s. We subsequently drove around Long Branch on two separate occasions: I took many photos and videos.

Man who lived in a shack in Alderwood

In the current post I will highlight what Bill mentioned in the video. Bill’s story of a man who lived in a shack in a field in Alderwood, where the man kept goats, has prompted me to view the video once again. The image of the man and his goats has stayed with me ever since Bill spoke about this. It’s part of the history of the area. A transcript (inside of which I have embedded links to previous posts) of the video reads:

We’ll start off down by the river. And I explain to you, where the Hurricane Hazel was on the other side of the river where all them homes were down Island Road, where the old road used to be. And then we’ll take you up, I’ll show you where the house was, where the GO Station is — all that. And then where there was a farm there when you come around the bend, on the east side, when you go down the hill in Long Branch, before 41st Street. And I could point out where the gas stations were.

And then another time, we’ll go down there, and I’m show you where 25th Street: it wasn’t there, then. Mrs. Cruesen [I don’t know the correct spelling; if anyone can help on this, let me know] had a school for boys. Little chubby woman, I remember her name, I was only five years old. And I’ll show you the north side where the Tim Hortons and all that is. That was a horseshoe pitch. There was no houses, there was no stores. You could see all the houses on Fairfield Avenue [which runs parallel to and directly to the north of Lake Shore Blvd. West.] And I’ll point out everything I can remember, you know — and where the lumber yard, Barnet lumber on 24th Street.

And whatever, you know what I mean? We could do it all maybe in two evenings, spend an hour or something. Two evenings, you know what I mean?

One evening, and maybe a week later, we’ll do another evening. And we’ll go down there, I’ll show you where the Park Hotel was, you know, we could draw sketches and then you’ll have a good idea of what Long Branch used to be like.

Image from a previous post. We owe thanks to Robert Lansdale for Photoshop colour correction on this image of the 1958 fire at Long Branch Hotel. Alex Stewart photo. Click on the photo to enlarge it.

Yeah, where they tore the factory down, it was all a big apple orchard; where you go over the tracks because there was no buses up Brown’s Line or nothing. If you lived in Alderwood, like on Horner, you had to get off at Long Branch Avenue: go up there, over the tracks, and there was a path all the way up to Horner Avenue. And as you go over the bridge on Brown’s Line, the old bridge: when you come down the hill, it was Alcan Aluminum.

But from there to Horner Avenue there was nothing — just a big field. An old man had goats in there; he lived in an old shack he made, in the middle of a field. And he had goats there, yeah.

Comments from the 1950s

As well, at a third previous post, Garry Burke speaks about his family’s postwar house on Exmoor Drive:

My parents bought a little bungalow on Exmoor Drive, almost directly across from the Long Branch Loop. Great location. I recall my mother telling me the mortgage was a whopping $10,500, and that people never, never paid off a mortgage.

With his prior permission, I’m pleased to share additional comments from recent email correspondence with Garry, who lives in Oro-Medonte, Ontario:

Wow! We were on a gold mine! My family moved into 24 Exmoor in July 1955. The mortgage $10,500. My mother mumbled we would never pay it off. But after having endured seven years of very cramped quarters in the Army Camp and Staff House, that little house was the Promised Land. And out the front door, and down a slight embankment, was the TTC Loop. Literally curbside public transit.

Alas, two years later our place, and six other “strawberry boxes,” were expropriated when the old bridge on Brown’s Line over the CN tracks was replaced. There is just green space there now where those homes stood. Why in the hell were they torn down??? We relocated to Alderwood, and a good hike to public transit.

I shake my head at those monster million-dollar dwellings on our little street. Pure greed. That’s not the lovely, tidy working-class neighbourhood of my youth.

In a subsequent email, Garry adds:

Haven’t been back there for five years, but I noticed that the lovely maple tree that my mother adored just outside our kitchen window is still there. So glad it survived the demolition of our little house in the autumn of 1957. But as I said before, there is just green space there now. I don’t think it’s a park. So why were seven or eight homes, including ours, expropriated?

Comments about community organizing

I am impressed with and inspired by the work of the Long Branch Neighbourhood Association. Although I moved from Long Branch to Stratford west of Toronto with my family in 2018, I remain an associate (non-voting) member of the association. I strongly support its work. This group is a strong source of inspiration for me.

The LBNA was founded and developed with extensive input from the residents of Long Branch. Based on my past volunteer work with the start-up of several nonprofit associations, locally, nationally, and internationally, it’s been my experience that taking time to get extensive grassroots input during the launch and development of any association is a key ingredient in ensuring that the organization is off to a great start.

I’m also very enthusiastic about the value of establishing, from the outset, a culture and set of operating procedures related to an organization’s leadership succession plan. Having such a plan in place is essential, in my observation of large numbers of organizations over several decades, in ensuring any organization’s long-term viability.

The Long Branch Neighbourhood Association has done a great job in years past in working with City of Toronto planners and the local community to develop the Long Branch Character Guidelines. Due to land use decisions at the provincial level, the character guidelines are no longer being followed to any great extent, so far as I know, when land use decisions are being made in Long Branch. This is readily evident from a reading of the Toronto Star article cited at the current post.

We owe thanks to the Toronto Star for its extensive reporting about land use decision making in Toronto. The reporting includes a valuable focus on data analysis of trends in housing prices. In years past, before its print version folded, due to its lack of a viable business model in the current Big Tech media environment, the Etobicoke Guardian also played a valuable role in informing residents regarding land use planning in Long Branch and elsewhere.

If you live in Long Branch, I strongly urge you to join the LBNA if you are not already a member. If you live elsewhere, I urge you to join as an associate member, as I have done, and make substantial donations if you can. Every dollar in support of community organizations such as the LBNA makes a huge difference. A current focus regards development plans for 220, 230 and 240 Lake Promenade and 21 and 31 Park Blvd. The link refers to a post from June 6, 2023. More recent messages such as this one are available through email updates from the association.

I was interested to read an Oct. 14, 2024 CBC article entitled: “Nobel in economics awarded for research into why countries with poor institutions don’t thrive: Win for Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James A. Robinson caps week of Nobel honours.”

The article prompted me to borrow a couple of books from the Stratford Public Library. Among them: Power and Progress: Our Thousand-year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity (2023).

A May 7, 2023 Guardian article is entitled: “Power and Progress review — why the tech-equals-progress narrative must be challenged.”

I found the book very inspiring — because the authors offer a sense of hope; they offer suggestions on how to reduce the endemic inequality in place around the world today.

An Oct. 24, 2024 Guardian article is entitled: ‘It’s a big lever for change’: the radical contract protecting Hamburg’s green space: Citizen power forced Germany’s greenest city-state into a binding agreement balancing housing and nature.”

I found the article of interest — in particular because I celebrate the fact that, with the community-driven project to save the former Parkview School property in Long Branch, a particular open space in Toronto was retained for the enjoyment of local students and residents.

A July 19, 2024 The Tyee article is entitled: “Patrick Condon Says This Is Why Housing Costs Are So High: The UBC prof and Tyee contributor blames runaway land speculation and offers fixes in his new book ‘Broken City.’ A Tyee exchange.”

I have borrowed Broken City (2024) from the Stratford Public Library. The Tyee article notes that the book’s “basic thesis is that unfettered speculation, fuelled by global wealth looking for asset investments, drives Vancouver land costs up so high they erase savings that can be delivered by building many units on a parcel instead of a few.

“That’s why, Condon says, new towers keep rising but their units cost pretty much the same as surrounding housing rather than pressuring price drops. If we don’t get a handle on land price super-inflation, he argues, we can’t deliver affordability. And he has some ideas about how to do that.”

What applies to Vancouver applies also to cities worldwide. The book looks at theories of economics from a perspective that, in Condon’s view, gives a person a better understanding of what is currently at play in the worldwide housing crisis. Condon promotes the views of a number of what he describes as “heterodox” economists. In my view this is a helpful book which offers a perspective well worth considering.

An Oct. 12, 2024 Politico article is entitled: “Opinion | The Little-Known Factor Driving up Housing Costs: Dirty Money: Dirty money is a major but little-recognized contributor to our housing affordability crisis.”

The article is of interest because it ties in well with what I have outlined in the previous Comments.

The work of Sarah Chayes comes to mind. I have read a couple of her books:

On Corruption in America (2020)

Thieves of State: Why Corruption Threatens Global Security (2015)

These books have enabled me to gain a better understanding of world history — including regarding Afghanistan, Africa, and the United States.

I also have an interest in how James C. Scott, who is known for addressing the negative features of modernity, views corruption. A previous post outlines his take, from 1972, on what corruption entails. However, I can add that the book is out of print; an online review offers an outline of its approach.

For anyone interested in the power dynamics of community organizing, a recent post about what I’ve learned over many years of volunteer work may be of interest.

An April 15, 2024 CBC article is entitled: “The dirty secret of the housing crisis? Homeowners like high prices: Large chunk of housing demand in Canada comes from investors.”

Also with regard to housing, another book-length study I’ve come across is Home Truths: Fixing Canada’s Housing Crisis (2024) by Carolyn Whitzman. You can access a review of the book here.

A June 1, 2024 Alberta Views article by Carolyn Whitzman is entitled: “Five Million Affordable Places to Live: How our government can end the housing crisis.” An excerpt reads:

The federal government had completely off-loaded responsibility for affordable housing to the provinces by 1993. Many provinces further off-loaded the costs of low-income housing to municipalities.

The consequences? Investing based on maximizing profits from existing housing—a practice sometimes called “financialization”—became much more lucrative than building new housing. Fewer homes were built in Canada in 2021 than were built in Canada in 1973. Over the past 30 years fewer than 10,000 new homes intended for low-income residents have been built in Canada.

A second excerpt reads:

Based on what’s worked in Canada and internationally, here are some ways to get costs down and increase the supply of housing.

For starters, governments should provide free or low-cost land. According to many international reports, good land policy is the basis of any successful affordable housing strategy. Large-scale government acquisition and disposition was the basis of both the post-war Victory Homes in Canada and the successful non-market housing programs of the 1960s and 1980s. Depending on the location and size of the project, land constitutes between 8 and 23 per cent of total cost.

This land should go to non-market development. According to a 2021 Canadian study based in Vancouver, non-market developers operating from a social mission instead of for profit can produce units that rent for 40–50 per cent less. Market developers—and their finance providers—expect returns ranging from 19 per cent to 28 per cent, depending on risk tolerance. And non-market developers maintain affordability over time, compared to government subsidies to private developers. Under the NHS, private developers have affordability requirements of only 10–20 years.

An Oct. 28, 2024 The Local (Toronto) article is entitled: “In the Annex and Crescent Town, Two Sides to Toronto’s Density Dilemma.”

The subhead for this opinion article is: “The Annex had fewer residents in 2021 than 1971. The towers of Crescent Town had far more. How the uneven, illogical densification pattern of the last 50 years created today’s Toronto.”

The article makes generalizations about residents’ associations – generalizations too broad, for my taste, if we consider, for example, the residents’ associations in Long Branch and Lakeview whose work is outlined in previous posts.

Blaming the polarization of Toronto on the efforts of residents (representing themselves in pursuit of their interests as residents) appears to me a debatable argument. That said, the article warrants a close read.

An excerpt reads:

Increasingly, these people also live in two kinds of places: horizontal neighbourhoods, where the homes are gracious and gabled, and vertical neighbourhoods, where they’re stacked high. In a meaningful way, the story of Toronto—a city in the midst of a housing emergency—is the story of how these two neighbourhoods interact. People in the horizontal city often fiercely oppose signs of verticality in their midst. And so towers—the kind that bring necessary density—are built mainly where they already exist, or they aren’t built at all. By seeking to bring a tower into the heart of the Annex, Walmer was violating a sacred Toronto taboo. Would the neighbours allow it to happen?

A second excerpt reads:

One would imagine that, given the terrible state of 500 Dawes, renters would be abandoning it in droves. In fact, the building is in high demand, because all Toronto buildings are. And it isn’t only destitute people who are moving in. “We’re seeing an influx of young professionals,” says Endoh. “We have nurses, skilled trades people, and law clerks. 500 Dawes is the only place they can afford.” A one-bedroom unit rents for $1,800—a total rip-off and the best deal in town.

We are dealing with larger issues related to how land has been dealt with in Indigenous and colonial history. Among valuable overviews is:

Imperial plots: women, land, and the spadework of British colonialism on the Canadian Prairies (2016)

Sarah Carter

Summary/Review:

“Sarah Carter’s “Imperial Plots: Women, Land, and the Spadework of British Colonialism on the Canadian Prairies” examines the goals, aspirations, and challenges met by women who sought land of their own. Supporters of British women homesteaders argued they would contribute to the “spade-work” of the Empire through their imperial plots, replacing foreign settlers and relieving Britain of its surplus women. Yet far into the twentieth century there was persistent opposition to the idea that women could or should farm: British women were to be exemplars of an idealized white femininity, not toiling in the fields. In Canada, heated debates about women farmers touched on issues of ethnicity, race, gender, class, and nation. Despite legal and cultural obstacles and discrimination, British women did acquire land as homesteaders, farmers, ranchers, and speculators on the Canadian prairies. They participated in the project of dispossessing Indigenous people. Their complicity was, however, ambiguous and restricted because they were excluded from the power and privileges of their male counterparts. Imperial Plots depicts the female farmers and ranchers of the prairies, from the Indigenous women agriculturalists of the Plains, to the land army women of the First World War.”

Also:

The great land rush and the making of the modern world, 1650-1900 (2003)

John C. Weaver

Summary

This work describes the appropriation and distribution of land by Europeans in the new world. By integrating the often violent history of colonization of this period and the ensuing emergence of property rights with an examination of the decline of an aristocratic ruling class and the growth of democracy and the market economy, John Weaver describes how the landscapes of North America, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa were transformed by the pursuit of resources. He also underscores the tragic history of the indigenous peoples of these regions and shows how they came to lose possession of their land to newly formed governments made up of Europeans with European interests at heart. Weaver shows that the enormous efforts involved in defining and registering large numbers of newly carved-out parcels of property for reallocation during the Great Land Rush were instrumental in the emergence of much stronger concepts of property rights and argues that this period was marked by a complete disregard for previous notions of restraint on dreams of unlimited material possibility.

As well:

Seeing like a state: how certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed (1998)

James C. Scott

Summary

Compulsory ujamaa villages in Tanzania, collectivization in Russia, Le Corbusier’s urban planning theory realized in Brasilia, the Great Leap Forward in China, agricultural modernization in the Tropics – the 20th century has been racked by grand utopian schemes that have inadvertently brought death and disruption to millions. Why do well-intentioned plans for improving the human condition go tragically awry?

The industry of ‘urban solutions’ may demonstrate some features of ‘seeing like a state.’ That’s what occurs to me after reading a Nov. 13, 2024 The Tyee article.

The article underlines that it’s a great idea to define clearly what a widely used term such as ‘urban solutions’ actually means. An excerpt reads:

The word “solutions” seems to lack concrete meaning, and her dissertation saw her wading through other vocabulary like “hackathons,” “sprints,” “acceleration,” “nudges,” “thought leadership” and “change-making.”

One interviewee who uses the term “solutions” frequently in her speeches reacted almost defensively when Bok asked her exactly what it meant. The interviewee turned the question back onto Bok, before saying, “It can be anything under the sun, you know.”

A second excerpt reads:

“There was a normalization of what people in the industry referred to as ‘best practice’ without any sense of irony at all,” said Bok. “If everything’s a ‘best practice,’ then what’s actually the best? I think that is taken for granted by people who are part of this industry.”

The vagueness, she said, is intentional and strategic. If an idea appears to be common sense, who can disagree with it? After all, who wouldn’t want their city to be “smarter” or more “resilient”?

Also with regard to the pursuit of solutions – a commendable project toward which each of us has the capacity, provided we approach the task with wisdom, to meaningfully and substantially contribute – I’ve been reading Question Authority (2024). The latter book skilfully and cogently outlines how we as human beings can best seek to make the world a better place. A worthwhile, philosophical read.

Also of interest, a Jan. 23, 2015 Guardian article is entitled: “Owning the Earth: The Transforming History of Land Ownership by Andro Linklater – review: The historian’s final book is a remarkably wide-ranging and erudite study of the global history of ‘the private property society.’”

Equally of interest is a Nov. 12, 2013 Kirkus Reviews article which describes the book as “Vast, evenhanded and worthy of rumination.”

Of additional interest: A Nov. 12, 2024 CBC article is entitled: “Life in Limberlost.”

An excerpt reads:

“Once a family’s life stabilizes, it’s very difficult to move on to purchasing their own small home or renting something else. It’s no longer a feasible option for people because of the housing crisis,” says Pam Cullen, the executive director and chaplain at the London Community Chaplaincy, which uses Unit 136 as a home-base for its programs, services and resources in the townhouse complex. It delivers similar services at a public townhouse complex in London’s south end.

“The housing crisis is the biggest challenge. Families cannot transition to another form of housing and that creates extra long wait-lists for people in crisis who need rent geared to income.”

A Nov. 12, 2024 New York Times article is entitled: “Why ‘Affordable Housing’ in New York City Can Still Cost $3,500 a Month: Soaring rents and few options have made it hard for average people to live in the city. Even “affordable” units often cost too much.”

An excerpt reads:

It may seem that this is a problem of semantics. But the terms we use to think about affordability matter, especially when politicians create policies designed to address the overall issue.

One takeaway: What people might actually consider affordable is relative. Cheap rents farther out from business districts or the city core and its subway lines may also mean higher transportation expenses if you end up needing a car.

Someone with a high income and no student loans may be able to easily spend 50 percent of their earnings on rent. Another person who has to be a caretaker for a sick family member might find it difficult to spend even 30 percent of their income on housing.

The term “affordable housing” fails to take into account all these nuances. That makes solving New York City’s housing crisis all the more difficult.

Worth study: Our perception of those among us who are homeless.

Gerrard, J., & Farrugia, D. (2015). The ‘lamentable sight’ of homelessness and the society of the spectacle. Urban Studies, 52(12), 2219-2233.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014542135

An excerpt reads:

Our discussion rests on the premise that in order to ‘understand’ homelessness, it is imperative to consider how the notion of homelessness as a ‘social problem’ has become discursively created. We therefore bring together theories of the Other, everyday interaction, and consumer capitalism in order to examine the ways in which the ‘sight’ and ‘scene’ of homelessness is created through discourses, through bodies, and through the cultural logic of capital. Focusing on the presence of homelessness in public space, we draw in particular upon Erving Goffman and Guy Debord to explore the ways in which everyday encounters with homelessness perpetuate discourses of the Other and dysfunctionality, bolstering the notion that homelessness is ‘out of joint’ in relation to the spatial and aesthetic logic of capital and capitalism. In other words, the ‘sight’ and ‘scene’ of homelessness appear as stains and blights on the city space, whilst the infiltration of capital in public space appears customary and common sense.

A second excerpt reads:

We set out our discussion in three acts. First, we reflect on the creation of visual representational discourses of homelessness, and their place in the popular, academic, and media portrayals of homelessness. Drawing on Erving Goffman’s development of the social ‘encounter’ and the constitution of social stigma, we consider the public nature of homelessness, and the visual and bodily dimensions of everyday ‘encounters’ with homelessness. Second, critically engaging with Guy Debord’s society of the spectacle we contextualise the ‘sight’ of homelessness within the broader social relations of consumer capitalism. We argue that the sight of homelessness cannot be separated from the broader spectacle of capital, and the proliferation of the image – and social relations of – commodity consumption in and through public space. Here, we explore the diverse ways in which homelessness is ‘Othered’ within the normative social relations of capitalism, including as a romantic life apart and as a stigmatised symbol of failure. Third, we conclude by turning to a consideration of how the society of spectacle comes to be lived and felt by people experiencing homelessness.

A limitation of the paper is that it largely restricts the theoretical framework, and the ensuing discussion, to late capitalist society. As noted at a previous post, the aversion to individuals who are categorized as “asocials” was also a feature, for example, of regimes in Germany and the Soviet Union in the 1930s and 1940s. That said, this is an interesting article and well worth a close read.

A Nov. 30, 2024 Guardian article is entitled: “My friend was a popular, promising artist – how did he end up on the streets of Portland, addicted and dangerous?”

The subheading reads: “When I first met Evan B Harris he was fizzing with talent and kindness. So I was shocked to hear he had become homeless and out of control. What happened to him is a story playing out in cities across America.”

A Dec. 3, 2024 New York Times article is entitled: “America’s Hidden Racial Divide: A Mysterious Gap in Psychosis Rates.”

The subhead reads: “Black Americans experience schizophrenia and related disorders at twice the rate of white Americans. It’s a disparity that has parallels in other cultures.”

An excerpt reads:

The emphasis on divergent rates as a real phenomenon — and not just a product of misdiagnosis — pushes against a core tenet of contemporary American psychiatry. Since around 1980, mainstream psychiatry in the United States has asserted what’s known as the biomedical model, an approach that tries to understand and treat the brain much like any other organ. The model views psychiatric conditions in predominantly physiological and often genetic terms. This is the case, above all, with psychotic disorders, probably because their symptoms can appear so alien, so much a manifestation of faulty neurological wiring. Under the sway of the biomedical model, American psychiatry’s prevailing assumption has long been that because psychosis is primarily genetic, the prevalence of the disorder should be fairly equal across populations and shouldn’t be overly affected by societal forces.

“This isn’t the thinking everywhere in the world,” Roberto Lewis-Fernández said when we spoke about American psychiatry’s concentration on what he called “the figure and not the ground — not the context in which the figure sits.” Lewis-Fernández has led marginally successful efforts to widen the lens of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the diagnostic bible of U.S. psychiatry, to complicate the biomedical model. “British thinking has been focused for much longer on contextual factors. One reason why the U.S. is more focused on the organism is our incredible focus on individualism. We tend to not want to agree that there is a collective world that impacts some more than others and creates pathology in certain groups.”