In December 1945, Mavis Gallant wrote a feature article for the Montreal Standard about a Christmas pageant at Cartierville School

We owe many thanks to Helen Meredith, who let me know about an article about Cartierville School that Mavis Gallant wrote in 1945; she let me know, as well, about a Gazette article about a book featuring stories Gallant wrote, 1944 to 1950, for the Montreal Standard.

Cartierville School burned down in April 2024. The school, along with nearby Marlborough Golf and Country Club, is now physically absent from the local scene. All that remains of the school and golf course, located near Gouin Boulevard just south of the Riviere des Prairies, are the memories and artifacts we have the occasion to share among us.

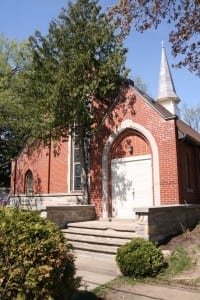

May 2015 photo of Church of the Good Shepherd, across the street from where Cartierville School was located. Scott Munro photo

As the link in the previous sentence notes, the Riviere des Prairies was, it is said, named after somebody who got lost on the river one day (I have added a link to the following quotation):

The Des Prairies River was named after a man named Des Prairies. One day, he was sailing on the river. Thinking he was on the St. Lawrence, he got lost. His mistake led people to name the river that separates the Island of Montreal from Île Jésus after him.

Click here for previous posts about Cartierville School >

Click here for previous posts about the Marlborough golf club >

Click on the photos to enlarge them.

Marlborough Golf and Country Club

Bruce Miller, now living in Scottsdale, Arizona, has commented, in a Dec. 17, 2024 message about the Marlborough golf club:

Hello Jaan,

It is about 1 year since anyone posted info on your golf site. My guess is, that no one will weigh in going forward……..folks have simply “aged out”.

It was so much fun for a few years, as “old timers” somehow found the site….like me.

One of our sons who also lives nearby in Scottsdale, has a wall of fame in one of his rooms. There is a photo of my Dad, taken at Marlborough around 1949. The golf Club used to post 8 X 10 framed photos of their Members on the walls of the Men’s Bar. When the Club was sold, the photos were given to Members who wanted them.

When I visit my son and see my Dad’s photo, it brings back memories, including your long running Marlborough golf site.

An additional message of Dec. 18, 2024 reads:

I forgot to mention that I also have a photo of my Mom, which was in the Ladies Lounge. The ladies hung some photos like the men, however, limited to fewer Members, ladies Champions etc. My Mom was President of the ladies association at the golf club.

Back then, ladies were treated like 2nd class citizens at golf clubs. At Marlborough, the ladies had their own 9 hole course, and were only allowed on the 18 hole course on Sunday afternoon with their husbands. Men never went near the ladies 9. My Dad never played with my Mom.

As a feature writer at the Montreal Standard, Mavis Gallant’s salary remained half that of her male colleagues

At a previous post I’ve noted that, in his role as a golf course architect in the 1920s, Stanley Thompson (1893-1953) designed the Marlborough Golf and Country Club. The website of the Stanley Thompson Society describes the connection as follows: “Designed by Stanley Thompson in 1923 as an 18 hole championship course and a 9 hole ‘ladies and beginners’ course, the course opened in 1924. The course no longer exists.”

[Update: In a comment at a previous post, Bob Carswell reports the course closed in 1956. In the event anyone can locate archival newspaper articles or other documentation about the closing, please contact me at jpill@preservedstories.com. I would be interested in sharing such details in a post at this website.]

Klaas Vander Baaren notes that this photo from a previous post “shows a caddy playing early. Caddies were allowed to play the women’s course at times. Walking from ladies 5th green to ladies 6th tee. The left side of the 6th fairway are the train tracks.” Photo source: Klaas Vander Baaren.

I was reminded, after reading about how women golfers were treated as second-class citizens in the 1940s, that when Mavis Gallant worked as a feature writer at the Montreal Standard starting in 1944, she was paid half as much as her male colleagues.

At a previous post I refer to a Jan. 20, 2025 Literary Hub article entitled: “Chasing Mystery Through Fiction: On the Life and Literary Career of Mavis Gallant: Garth Risk Hallberg Remembers a Master of the Short Form.” An excerpt reads:

At twenty-three [when working as a journalist at the Montreal Standard], she interviewed Jean-Paul Sartre. Yet to the degree that Gallant was capable of recognizing the figure she cut, it would have been all the more galling that her salary at the Standard remained half that of her male colleagues. In the Linnet Muir series, as in “Its Image on the Mirror,” she connects the brittle hierarchies of bureaucratic existence (“the trace of Empire…the old men with their medals”) to those of Quebec as a whole, both English- and French-speaking. Authority may have devolved to an offstage blur, where “behind frosted-glass doors lurk male fears of female mischief,” but its edicts persist: “a creeping, climbing wash of conflicting and contradictory instructions [that] threatens to smother you.”

Mavis Gallant at her typewriter in the newsroom of the Montreal Standard, where she worked as a feature writer from 1944 to 1950. Library and Archives Canada PA-115248, courtesy of Véhicule Press. The photo appears in The Gazette (Oct. 19, 2024) and The Walrus (Feb. 22, 2025)

Competing visions regarding British empire

The above-noted excerpt refers to the legacy of the British empire. An excerpt from a previous post sums up things I’ve learned about the empire:

In a previous post I describe a British empire monument unveiled in Montreal in 1907, dedicated to Canada’s involvement in the Boer War. The history of the Boer War is part of the history of the British empire.

It occurs to me, in this context, that it’s a great idea to picture a continuum of contrasting options, when we consider how a range of historians have approached the history of the empire.

At the one end of such a continuum, the British empire can be viewed as akin to a big happy family, where everybody knew their place inside of a hierarchy based upon class and status – and regarding which it has been claimed that everybody had a comforting sense of belonging.

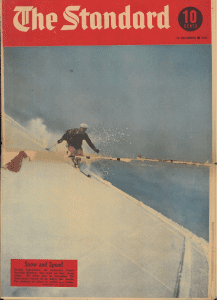

The Standard magazine, Dec. 22, 1945. Caption reads: Snow and Speed: Famed Laurentian ski instructor Frank Scofield displays fine form on fast, steep slope. He takes part in Canadian Ski Instructors’ school at St. Adèle this month. For pictures of skiers in action see Inside. [Photo credit: name is illegible]

At the other end of such a continuum, the empire can be viewed as a vast, all-encompassing enterprise which was structured in accordance with a rigid, all-pervasive, and brutal system of organized violence.

George Orwell has brought attention to the latter end of the continuum.

On the other hand, it may also be emphasized that the legacy of violence of the British empire – including, indeed, what the contemporary historical record has documented as its extensive experience, during its colonial heyday, in the incessant waging of pervasively lawless, irregular warfare – was productively brought to bear on the Allied side during the Second World War.

Mavis Gallant wrote for the Montreal Standard, 1944 to 1950

Helen Meredith has shared with me a PDF file of text and photos of a Dec. 22, 1945 Standard magazine article about Cartierville school by Mavis Gallant. The magazine sold for 10 cents.

I have come across an online reference by Linda Seccaspina which reads: “The Montreal Standard, later known as [The] Standard, was a national weekly pictorial newspaper published in Montreal, Quebec, founded by Hugh Graham. It operated from 1905 to 1951.”

A Dec. 3, 2012 Canadian Encyclopedia article by J. L. Granatstein notes that

The Montreal Standard began as a Saturday newspaper in 1905, an attempt to create a Canadian version of the Illustrated London News. The initial object was to provide a serious yet lively look at the week’s events through photographs and news stories. During WWI in particular, and to a lesser extent during WWII, this format was both popular and successful. Over time, the Standard became less news oriented and more a feature-filled weekly, with comics, recipes and fiction jostling for space with advertising and illustrations. The original broadsheet format changed to tabloid size, but by the beginning of the 1950s Montreal Standard seemed out of date. In 1951 its publishers conceived the idea of WEEKEND MAGAZINE, and the Standard’s staff was absorbed into the new periodical. See also NEWSPAPERS.

In a recent message, Bruce Miller has commented:

I remember the Standard very well … When I was 12 years old, I had a [Montreal] Star newspaper route around our neighborhood, Snowdon, where we lived. The weekend edition of the Star included the Standard, which was sent to me in bulk, and I had to fold them into every newspaper before delivering.

Click here for Canadian Encyclopedia article about newspapers in Canada >

Helen Meredith has also reminded me of a new book, which I will describe below, about Mavis Gallant’s work as a feature writer at the Montreal Standard from 1944 to 1950. I will also highlight a feature article by Gallant from December 1946, “A Wonderful Story.” The latter article serves as a great introduction to Gallant’s style of writing, in the event you have not encountered her work previously. So far as I can remember, this was the first article by Gallant that I have read.

The Dec. 22, 1945 Standard magazine article about Cartierville School reads as follows:

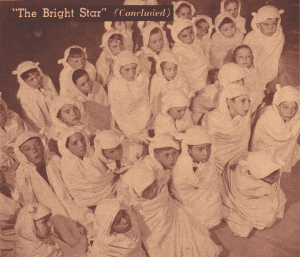

“The Bright Star”

School Children Act Out the Christmas Story

Story by Mavis Gallant

Photos by Louis Jaques

THE Christmas story, re-enacted as it has been for hundreds of years, is still at its simplest and best when done by children. Familiar with every detail long before they can read, they approach it as they might a fairy tale, remembering all the things they find most appealing – the Star, the snow, the Three Wise Men, and the Baby.

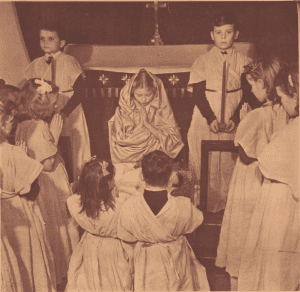

This year, the story was performed by the pupils of Cartierville School in a play called “The Bright Star,” written by Lenore Osborne, one of their teachers. The lines were mostly poetry and easy to memorize, and the play went on in the Church of the Good Shepherd, across the street from the school.

Janice Pratt, aged eight, played the Virgin Mary. She won the part after a close contest with three other girls and finally, to avoid trouble, her name was picked out of a hat.

Besides being pretty and looking like the conventional idea of Mary, Janice “likes acting and isn’t ascared,” which was a great help to the play’s directors because the sheep from Grades one and two had a tendency to easy panic. Bundled into bedsheets like cocoons they nearly suffocated pretending to be asleep, managed to gasp out one line: “It must be a birthday.” One sheep called Edna was so overcome by the first dress rehearsal that she could whisper nothing but “Abord-à-Plouffe,” the name of a town, when asked for her name and age.

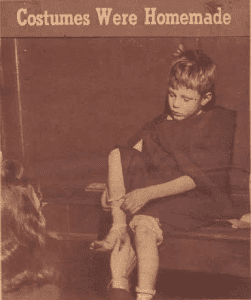

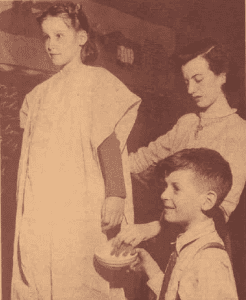

Costumes consisted of lengths of cheese cloth and dyed cotton, draped to create shepherd smocks and angel robes. The children found it easy to cope with lines like “I like babies,” harder to remember where to stare every time “Look yonder” was delivered.

IN THE CHURCH of the Good Shepherd at Cartierville, Quebec, a choir of angels sings a lullaby around the crèche. Doll, representing the Baby Jesus, was brought by one of the little girls. Entire student body of Cartierville School took part in the Christmas performance. Louis Jaques photo

Mavis Gallant’s keen visual and aural senses

Gallant’s style of writing strikes me as brisk and highly engaging: the main text, photography, and accompanying captions make for an easy to comprehend, informative, and highly evocative story-presentation. I am reminded of an October 2022 Literary Review of Canada article by Gregory Shupak entitled: “Remembering Mavis: When she looked out the window.” An excerpt reads:

To mark the centenary of Gallant’s birth, I recently revisited both her work and Mavis Gallant: The Eye and the Ear, a landmark study by Marta Dvořák, a scholar and a confidante of her subject. That 2019 book presents a compelling case that Gallant’s keen visual and aural senses were profoundly shaped by her immersion in art, film, and music. In what Dvořák calls a modernist assimilation of literary texts, visual culture, and music, Gallant submerged herself in Marcel Proust, James Joyce, and the Russians, as well as Pablo Picasso, Ella Fitzgerald, the composer Dmitri Shostakovich, and the film director Wallace Worsley. (She was, broadly, of the left, but that seems not to have determined her aesthetic tastes, as her fondness for the music of the Mussolini-admiring Stravinsky and the antisemitic Wagner evinces.)

The Walrus, Feb. 22, 2025, features “A Wonderful Country” by Mavis Gallant

A Feb. 22, 2025 Walrus article features a Montreal Standard story by Mavis Gallant. The article is entitled: “‘A Wonderful Country’: A Mavis Gallant Story Rediscovered: The celebrated writer on a newcomer who falls in love with Canada.”

The opening paragraphs read:

A Wonderful Country

December 14, 1946

I CALLED HIM the Hungarian because I couldn’t pronounce his name. If he had a name for me, I never heard it. We weren’t what you’d call chummy.

It was early in the war then, when there were still houses to rent and apartment hunters who could afford to be choosy. I was a junior assistant in a real estate office, making next to nothing and chasing every cent. That was how we met.

If it had been any other way, we might have become friends, because we were both so lonely in Montreal. But as it was, he needed a furnished house and I needed a commission, so I never bothered to ask if he liked Canada or anything else. I just waved street maps and leases and talked fast.

I was very impressed with this article. I thought it remarkable how effectively, and with such good humour and warmth, the author brought the scene to life.

Changes in world media ecosystem since the 1940s

The ad for Tavannes Watches (“Time the World”) on Page 14 of the Standard article reminds me that in the 1940s, the newspaper industry had a successful business model based on sale of advertising. The text for the ad reads:

Appealing to ladies by the dainty loveliness of their styling and to men for their smart masculine design … Tavannes Watches hold friends throughout long years by the truthful accuracy of their trouble-free time-keeping. Sold throughout Canada from twenty-nine dollars and seventy-five cents up.

There are multitudes of studies available which underline how drastically the media ecosystem has changed with advent of the internet and social media.

In that context, two sources I have found of value in my current reading, about such a drastic and dramatic change in the world’s media ecosystem, include The Flooded Zone: How We Became More Vulnerable to Disinformation in the Digital Era – Chapter 3, by Paul Starr, from The Disinformation Age (2020). This is an Open Access document from Cambridge University Press.

SWADDLED IN SHEETS, a flock of sheep from Grades I and II stare fixedly at the Star of Bethlehem. Silent and earnest, they rehearsed for days. Louis Jaques photo

An excerpt reads:

Compared to the patterns in the mid-twentieth century, the news media and their audiences have been reconfigured along political lines. Americans used to receive news and opinion from national media – broadcast networks, wire services, and newsmagazines – that stayed close to the center and generally marginalized radical views on both the right and the left. Now the old gatekeepers have lost that power to regulate and exclude, and news audiences have split. By opening up the public sphere to a broader variety of perspectives, including once-shunned radical positions, the new environment should have advanced democratic interests. But the forms of communication have aggravated polarization and mutual hostility and the spread of disinformation.

While the mass-media gatekeepers no longer have as much power as they once had to interdict falsehood, the digital revolution has given rise to new forms of organization that could perform that function. The most important of these are the corporations that control the platforms on which news and debate travel. That has put the platforms and the people who own and run them at the center of the political conflict over disinformation.

The Adaptable Country (2024)

Another exemplary source, for getting up to speed on the current media landscape, is a study by Alasdair Roberts: The Adaptable Country: How Canada Can Survive the Twenty-First Century (2024).

MARY was played by Janice Pratt, who is, at the age of eight, a serious young actress. Louis Jaques photo

An excerpt (p. 31) reads:

The dire health of Canada’s magazine industry was examined by the 1961 O’Leary Commission, which warned that “communications are the thread which binds together the fibers of a nation … [They] are as vital to its life as its defences, and should receive at least as great a measure of national protection.” The shuttering of newspapers in the 1970s led to the Kent Commission, which predicted that the industry would soon be upended by a technological revolution. Canadians needed help in managing a blizzard of information, the commission warned, but newspapers might not survive to perform that function. Governments not only studied the public sphere. They also took measures to protect it, using every tool imaginable. The federal government began by subsidizing the distribution of newspapers and magazines by mail. It followed this initial action with the establishment of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 1936. In the post-World War II era, the federal government added restrictions on foreign ownership of media companies, limits on the re-broadcasting of foreign-produced shows, bans on the importation of foreign magazines, tax incentives for advertisers to support Canadian media, and cash grants to support the production of Canadian news and culture.

This bundle of interventions did not always work well. But imagine how much worse off Canada would have been in the twentieth century if none of these measures had been adopted. The country would have lacked the capacity to chart its own course, to test ideas and forge agreement on national strategy, just as the editors of The Canadian Forum warned in 1920: Adaptability would have been compromised as a result.

JOSEPH (Billy Fawcett) sits on piano stool, tries to look benevolent as shepherds Marilyn Hughes and Edith Wood come to “see the Baby.” Louis Jaques photo

I’m reminded of April 1966 Esquire article about Frank Sinatra by Gay Talese

At about the same time that I was reading “A Wonderful Country,” I also read an article by Gay Talese which I had learned about when visiting the Literary Review of Canada website. An excerpt from an editorial note by Kyle Wyatt in the April 2025 issue of the magazine reads:

Setting aside what I have edited myself, the magazine piece I have read the greatest number of times is, without question, Gay Talese’s “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” from the April 1966 issue of Esquire. The 15,000-word profile was Talese’s first assignment for the iconic men’s monthly, part of a six-story trial run with its editor, Harold Hayes. Considering that Ol’ Blue Eyes had rebuffed Esquire repeatedly in the past, it was always going to be a demanding initiation. But then the subject was under the weather when the reporter from New York landed in Hollywood, and he simply refused to talk.

The reference to this article prompted me to find an online version: You can read “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” Esquire, April 1966, at the “Official website of the acclaimed writer Gay Talese.”

MOST HARASSED shepherd was Ralph Stahan, son of Royals’ hockey player, who kept losing sandals. Louis Jaques photo

The opening paragraph reads:

FRANK SINATRA, holding a glass of bourbon in one hand and a cigarette in the other, stood in a dark corner of the bar between two attractive but fading blondes who sat waiting for him to say something. But he said nothing; he had been silent during much of the evening, except now in this private club in Beverly Hills he seemed even more distant, staring out through the smoke and semidarkness into a large room beyond the bar where dozens of young couples sat huddled around small tables or twisted in the center of the floor to the clamorous clang of folk-rock music blaring from the stereo. The two blondes knew, as did Sinatra’s four male friends who stood nearby, that it was a bad idea to force conversation upon him when he was in this mood of sullen silence, a mood that had hardly been uncommon during this first week of November, a month before his fiftieth birthday.

A Dec. 22, 2021 Literary Hub article by Gay Talese is entitled: “When New Journalism Was New: Gay Talese on His Legendary Esquire Profile of Frank Sinatra: On Trying – and Failing – to Interview Ol’ Blue Eyes.’

ANGEL ROBES are pinned on Ann Melville by teacher Lenore Osborne, who wrote Christmas play. Louis Jaques photo

The opening paragraph reads:

As one who was identified in the 1960s with the popularization of a literary genre known best as the New Journalism – an innovation of uncertain origin that appeared prominently in Esquire, Harper’s, The New Yorker, and other magazines, and was practiced by such writers as Norman Mailer and Lillian Ross, John McPhee, Tom Wolfe, and the late Truman Capote – I now find myself cheerlessly conceding that those impressive pieces of the past (exhaustively researched, creatively organized, distinctive in style and attitude) are now increasingly rare, victimized in part by the reluctance of today’s magazine editors to subsidize the escalating financial cost of such efforts, and diminished also by the inclination of so many younger magazine writers to save time and energy by conducting interviews with the use of that expedient but somewhat benumbing literary device, the tape recorder.

I would note in passing that I’ve been using tape recorders – and later digital recorders – for fifty years when conducting interviews. That said, I can see the point Talese is making: A reporter can, indeed, create exquisitely crafted, in-depth stories with apt quotations and observations – without ever turning on a recording device.

Talese has written a book – Frank Sinatra Has a Cold (2021) – with photography by Phil Stern and edited by Nina Wiener centred on the April 1996 Esquire article. Of related interest is an article entitled: “Origins of a nonfiction writer” by Gay Talese. The article is featured in Writing Creative Nonfiction: The Literature of Reality (1996) by Gay Talese and Barbara Lounsberry. Talese’s earlier magazine pieces – and his account in the above-noted article of how he got started in journalism – are of particular interest for me.

ANGEL GABRIEL (Paul Furcal) points to “yonder star,” shows Three Kings way to Bethlehem. They carry gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. Louis Jaques photo

Paris 1968

A November 2018 Literary Review of Canada article by Susan Whitney is entitled: “The Myth of 1968: Clinging to pictures of a revolution in France.”

An excerpt reads:

The memory industry was in overdrive in Paris this summer as France marked the fiftieth anniversary of “Mai 68,” that defining month when major Parisian arteries turned into seas of flag-waving young people and occupied high schools and universities. After violent clashes between students and security forces on May 10 left 367 wounded, and huge swaths of Paris’s Left Bank resembling a war zone, industrial workers joined the protests. Ten million workers were soon on strike, many occupying their factories and workplaces. What began as a challenge to a sclerotic education system had morphed into a crisis that shook president Charles de Gaulle’s government and brought France to the edge of revolution. May 1968 has been remembered in France, historian Michelle Zancarini-Fournel wrote in 2008, as the most important event since the end of the Second World War.

CAROLLERS come in carrying lanterns, sing “While shepherds watched their flocks by night.” They wear street clothes to give effect of winter. Louis Jaques photo

Despite the reams of words written about May 1968, Mavis Gallant’s account of daily life during these tumultuous weeks continues to stand out. With an unerring eye for detail, Gallant took in demonstrations, talked to protesters and bystanders, and pondered the remains of charred and upended automobiles. It was not the cars of the rich that got torched, she reported in The New Yorker, but those of more modest French citizens, for these were the ones that could be lifted and pushed around easily – the ones, in other words, that could be used by students in the building of barricades. When at home, Gallant watched the “night of the barricades” unspool outside her apartment windows. On calmer days, she carried her transistor radio from room to room so as not to miss the slightest scrap of news. By May 22, French newscasters had given up reporting what was closed, preferring instead to focus on the few services that continued to be available: gas, water, and electricity.

I’ve found it of interest to read “The Events in May: A Paris Notebook – I” and “The Events in May: A Paris Notebook – II.” The two articles originally appeared in The New Yorker; I accessed them through a library copy of Paris Notebooks: Essays and Reviews by Mavis Gallant (1986).

Montreal Standard Time (2024) highlights newspaper stories by Mavis Gallant

IN FINAL TABLEAU, Gabriel blows his horn and everyone gathers around the crèche. The sheep, who have performed admirably, are by this time quite flushed from the strain of bending over. Also uncomfortable were the kings, whose beards were stuck on with adhesive tape. Louis Jaques photo

From Helen Meredith I’ve learned of an Oct. 19, 2024 Gazette article by Marian Scott entitled: “Another side of literary giant Mavis Gallant: the Montreal journalist.” The article highlights Montreal Standard Time: The Early Journalism of Mavis Gallant (2024). An excerpt reads:

Now, a decade after her death in Paris at 91, a new book provides the prequel to Gallant’s literary career. Montreal Standard Time: The Early Journalism of Mavis Gallant presents 38 of her pieces for the Montreal Standard from 1944 to 1950, selected from among about 125 bylined feature articles. (She wrote an estimated 125 other pieces for the paper, including radio and film reviews.)

On topics from refugees to unwed mothers, and from rising stars of Quebec literature to why Canadians are so dull, the articles reveal a budding talent with boundless curiosity and a razor-sharp wit. Written as Europeans displaced by war were pouring into the city, they explore themes that would permeate her fiction: lives of transience and exclusion; the world of childhood; society’s attitudes toward female deviance. And they showcase Gallant’s ability — exceedingly rare in that era — to move seamlessly between Quebec’s two language solitudes.

The volume offers a new perspective on a writer who uniquely captured Montreal, even if she never again lived in her hometown.

The story about the Christmas pageant in 1945 reminds me of this photo from a previous post of Jim Carswell, Lesley Carswell, and Bob Carswell, about 1953, at the Cartierville School annual carnival. Source: Bob Carswell

Mavis Gallant was astutely aware of the point of view of children

A Feb. 18, 2014 New York Times article by Helen T. Verongos is entitled: “Mavis Gallant, 91, Dies; Her Stories Told of Uprooted Lives and Loss.” An excerpt reads:

Ms. Gallant also endowed children with special powers that vanish as they grow up. In “The Doctor,” she wrote: “Unconsciously, everyone under the age of 10 knows everything. Under-ten can come into a room and sense at once everything felt, kept silent, held back in the way of love, hate and desire, though he may not have the right words for such sentiments. It is part of the clairvoyant immunity to hypocrisy we are born with and that vanishes just before puberty.”

Reviewers underline that Mavis Gallant was strongly aware that young children in general are very much tuned into what goes on in the world. When I was reading the excerpts, I was reminded that, in my late adolescence in Montreal, one day it had occurred to me that, at the age of 12, I knew as much about life as I ever would know. I was aware at that age that, whatever I would know as an adult, nothing would be added to what I knew as a child.

A corollary was that, with notable exceptions, adults as a rule tended not to be aware of what young children tuned into as a matter of course – about how the world works, and what life appears to be about: things observable by any attentive person, such as a child. I hadn’t thought of this memory until now, when I’ve been reading articles, essays, and stories by Mavis Gallant – and commentaries about her life and times. I can add this: When I was a young adult, very young children would, in a sense, let me know that it would be a good idea if I were to spend my years working with children. That’s how I became a teacher.

Paris Notebooks (1968): “What Is Style?”

An excerpt (pp. 176-7) from an essay in Paris Notebooks (1968) by Mavis Gallant reads:

Leaving aside the one analysis closed to me, of my own writing, let me say what style is not: it is not a last-minute addition to prose, a charming and universal slipcover, a coat of paint used to mask the failings of a structure. Style is inseparable from structure, part of the conformation of whatever the author has to say. What he says – this is what fiction is about – is that something is taking place and that nothing lasts. Against the sustained tick of a watch, fiction takes the measure of a life, a season, a look exchanged, the turning point, desire as brief as a dream, the grief and terror that after childhood we cease to express. The lie, the look, the grief are without permanence. The watch continues to tick where the story stops.

I am reminded that the present moment is the sole portal that is available to us, with regard to our access to the past.

Stories connected with Cartierville School

Another story concerned with Cartierville School can be found at a previous post – which describes how the Bois-de-Saraguay not far from the school was saved from destruction. The story demonstrates the power of human agency; it underlines what can, under specified conditions, be accomplished when local residents, wherever they may be living, work together effectively and with strong determination in pursuit of shared interests.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

I like to look back on the days when I was a Grade 4 student at Cartierville School in the mid-1950s. There is tremendous value in looking back; such a process of reliving days gone by helps – in a significant way – to keep a person’s mind alert as the following post underlines:

April 23, 2022 New York Times article refers to study that found that median survival was seven and a half years longer for those with the most positive beliefs about aging

I think as well of a previous post:

Counterclockwise (2009) and Memory Fitness (2004) are two evidence-based resources addressing the passage of the years

An excerpt reads:

Counterclockwise (2009)

A book with a good overview of relevant research in this general area is: Counterclockwise: Mindful Health and the Power of Possibility (2009).

A blurb (which I’ve broken into shorter paragraphs, for ease of online reading) at the Toronto Public Library website, for the latter study, reads:

If we could turn back the clock psychologically, could we also turn it back physically? For more than thirty years, award-winning social psychologist Ellen Langer has studied this provocative question, and now, in Counterclockwise, she presents the answer: Opening our minds to what’s possible, instead of presuming impossibility, can lead to better health – at any age.

Drawing on landmark work in the field and her own body of colorful and highly original experiments – including the first detailed discussion of her “counterclockwise” study, in which elderly men lived for a week as though it was 1959 and showed dramatic improvements in their hearing, memory, dexterity, appetite, and general well-being – Langer shows that the magic of rejuvenation and ongoing good health lies in being aware of the ways we mindlessly react to social and cultural cues.

On same topic as in previous Comment, another post is entitled:

Mindfulness stands in contrast to mindlessness

An excerpt reads:

An Oct. 22, 2014 New York Times article is entitled: “What if age is nothing but a mind-set?”

The article describes an experiment in which a group of subjects in their senior years, who had graduated from high school many decades earlier, were provided an intensive array of sensory cues – such as music from the 1950s, among many other cues – that enabled them to experience their “younger selves” from their high school years, over a period of five days.

They were instructed to imagine that they were in their teens once again. All manner of suitable artifacts – vintage radio, black-and-white TV – were provided to help them to experience themselves as their younger selves.

The resulting mind/body effects – people sat taller, their sight improved, and their minds appeared sharper – that are described in the article are of interest.

I’m looking forward to learning in future if the initial experiment, described in the article, has been replicated.

Without replication, the evidence is interesting but not robust.

If you know of a replication of this study, I would be interested in details.

Update

I’ve received an update regarding Cartierville School from a site visitor who wrote on Dec. 28, 2025:

I have been travelling Gouin Blvd daily since September and sadly must update that Cartierville School has now been demolished (work wound up shortly before Christmas). As previously reported, there had been a major fire and the fenced off school had stood for 1.5yrs with sagging cindered beams. I guess the investigation/insurance was finally completed and the wreckers arrived in Nov. As for the asbestos, they were hosing the ruins perpetually even in Arctic conditions so there was probably truth to that theory. My on-line research unearthed an article (in French) that Montreal has ear-marked the land for a subsidized housing project. A construction trailer remains on the lawn although all debris was trucked away. This collective of memories is now more important than ever!!