The link between James C. Scott’s Domination and the Arts of Resistance (1990) and current conditions

The current post concerns an American Anthropologist (2005) article by Carol J. Greenhouse regarding James C. Scott’s Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (1990).

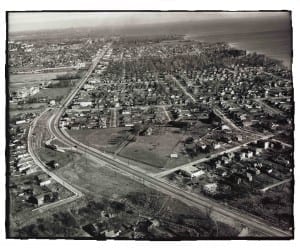

Aerial view looking east along Lake Shore Blvd West from near Long Branch Loop, Ontario Archives Acc 16215, ES1-814, Northway Gestalt Collection. The original Colonel Samuel Smith house (a log cabin to which extensions and siding were added over the years) is visible at the centre of the photo. Click on photo to enlarge it.

My interest in the article stems from previous volunteer work regarding land use planning in Toronto. I was involved for example with a community-wide letter writing campaign in 2011 to keep Parkview School, now named l’École élémentaire Micheline-Saint-Cyr, in public hands. This effort involved decisions made by levels of government whose use of language was straightforward.

Sometimes, however, as I’ve also learned, power uses language in a form whereby up is down, in is out, and big is small. I’ve learned this from attending large numbers of committee of adjustment hearings in Toronto related to the question of what constitutes a “minor variance.”

Detail from July 21, 1905 survey prepared for Eastwood Brothers showing Eastwood Farm in Long Branch where Colonel Samuel Smith log cabin was located; cabin is in view alongside roadway at centre-right of survey.

A series of American Anthropologist (2005) articles about James Scott has added nuance to my initial understanding of how language sometimes functions.

Domination and the Arts of Resistance (1990)

A review by Daniel Little of Domination and the Arts of Resistance (1990) comments that the book “is about the experience of domination and indignity that power relations impose on the powerless.”

In this work, the reviewer notes, James Scott distinguishes between public transcripts which involve “the open interaction between subordinates and those who dominate” and hidden transcripts which involve a “discourse that takes place ‘offstage.'”

The discussion between Carol Greenhouse and James Scott takes place in a series of articles in American Anthropologist: Volume 107, Issue 3, September 2005.

The article by Greenhouse is entitled: “Hegemony and Hidden Transcripts: The Discursive Arts of Neoliberal Legitimation.”

Back view (facing south) of Colonel Samuel Smith farmstead house, located at what are now the school grounds of the former Parkview School in Long Branch. Originally a log cabin, built in 1797, the house had siding and extensions added to it over the years. Photo © Betty Farenick and family

The abstract reads:

In this article, I offer a reading of James Scott’s Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (1990) from an inverted standpoint: Whereas Scott’s focus is on resistance from below, mine is on resistance from above. My case study involves some of the more prominent legal and political responses to the attacks of September 11, 2001 – notably the President’s Military Order of November 13, 2001, establishing military tribunals for noncitizen detainees charged with terrorism. My analysis supports Scott’s thesis regarding the discursivity of resistance while challenging some of his conclusions regarding the form and content of hegemony, as read in the current neoliberal milieu. With respect to the military tribunals, I argue that their establishment represents an extension of executive power rehearsed prior to the attacks, and that the politicization of security in the United States involves institutions and issues that have long antecedents in partisan political terms.

Response by James Scott to article by Carol Greenhouse: the concept of hegemony

In response, Scott comments (I’ve added paragraph breaks):

K. Sivaramakrishnan and Carol Greenhouse both address the issue of hegemony, although each in a quite different and original way. Here is perhaps the place for a moment of self-criticism and a belated apology to the ghost of Gramsci himself. Strictly speaking, the task Gramsci set himself in his discussion of hegemony was to account for the relative quiescence of the working class in a political landscape of parliamentary democracy, in which they had the right to vote.

The term hegemony, as opposed to domination, was applied explicitly and exclusively to such settings because the vote was a key element in legitimating a political order in which all the other political assets – the means of production, landed property, the Church, the media, the school system, and the law – were firmly in the hands of the bourgeoisie and its allies.

View of l’École élémentaire Micheline-Saint-Cyr (formerly Parkview School) photographed from top of Aquaview Condominiums, November 2012. Click on photo to enlarge it. Jaan Pill photo

The right to vote and parliamentary democracy were both working-class achievements with real consequences and, at the same time, institutions that suggested the complicity and participation of the working class in creating a political order that was manifestly unfair. As such, the term hegemony is, strictly speaking, inapplicable to most of the settings (e.g., slavery, serfdom, caste, dictatorships) described in Domination and the Arts of Resistance (1990) and is only marginally applicable to the peasantry of Sedaka, the subjects of Weapons of the Weak (1985).

I ought to have used the term domination in its place. Although the authors of systems of domination also attempt to justify their rule in terms of the well-being of their subjects (e.g., paternalism, superior knowledge, security), they lack any institutions of apparent consent that are the very center of Gramsci’s attention. At stake for me in my Malaysian village fieldwork and in writing Weapons of the Weak, was the task of examining closely the struggle over material appropriation and the struggle over the moral high ground (aka ideology) in one small place. As a card-carrying political scientist, my inspiration was nothing more and nothing less than what every anthropologist takes for granted: namely, that no abstract force, collectivity, or system ever arrives at the door of human experience, except as it is mediated by concrete, particular human “carriers.”

View of school grounds looking north toward Lake Shore Blvd. West, at former Parkview School in Long Branch. The school, which was saved from demolition following a community-wide letter writing effort, was subsequently renamed as St. Josaphat Catholic School; its current name is l’École élémentaire Micheline-Saint-Cyr. Jaan Pill photo

Not the landed aristocracy in general, but a particular lord of the land, with his own family history, his own personality, in this particular place. Not capitalism, in general, but this moneylender, this trader, this factory boss, and this foreman, each with his or her own personality, ethnicity, and routines. One of the most impressive examples of how illuminating it can be to attach a historical process to its actual historical bearers is Hillel Levine’s 1991 work, Economic Origins of Antisemitism. He shows how anti-Semitism barred Polish Jews from a host of occupations and drove many into moneylending, cropbuying and production loans, retail trade, and the sale of alcohol.

View of new main entrance stairs, one of many new landscape features at École élémentaire Micheline-Saint-Cyr, 85 Forty First St. in Long Branch. Jaan Pill photo.

Thus, the Jew came, willy nilly, to occupy the last rung above the peasantry in a capitalist world of markets and credit. And, thus, it was in a capitalist slump that the Polish peasant often experienced the shocks in the form of an (also relatively powerless) Jewish shopkeeper, moneylender, and rent collector. And thus, finally, it was that rage at personal ruin originating in the financial centers of New York and London that took, in the Polish countryside, the form of anti-Semitism. Weapons of the Weak was an attempt to discuss class and ideology, leaving aside the abstractions of political science and sociology.

Archaeological remains of Colonel Samuel Smith homestead are located on school grounds of former Parkview School at 85 Forty First Street. The Ontario government announced on Aug. 25, 2011 that it would provide $5.2 million in funding to enable the school to stay in public hands. The sale of the school has turned out to be a good news story thanks to the efforts of Etobicoke-Lakeshore MPP Laurel Broten (subsequently Minister of Education); Ward 3, Etobicoke-Lakeshore TDSB Trustee Pamela Gough; Toronto Lands Corporation officials; large numbers of people who wrote letters in support of keeping the school in public hands; and several key individuals who shared strategic advice. Peter Foley photo

Repackaging of genuine resentments of subalterns

Scott adds:

Greenhouse’s article takes my ideas of the “official” and the “hidden” transcript into wholly new territory. In the process, she sees possibilities and subtleties to the analysis that, although I wish they were mine, are actually her own quite original inventions. To gloss what seems to me a powerful insight, she sees the key hegemonic move as the way in which the genuine resentments of subalterns-citizens are repackaged in a fashion that contributes to the political capital and projects of rule. Scapegoating minorities, draconian anticrime laws, and saber-rattling nationalism might fall in that category.

What is new, I think, is that it points to the link between the genuine fears of subalterns and the play of official discourse, much as Fredric Jameson (1981) shows in The Political Unconscious how advertising depends on popular hopes and utopias for its effect. Where virtually all my attention was devoted to the “hidden transcript” of subordinate groups, Greenhouse proposes a novel scheme for uncovering the deeper game behind official public acts.

Her brief but utterly convincing tracing of what she calls the “discursive trails” behind President Bush’s Military Order of November 13, 2001, which established military tribunals for noncitizen detainees, shows the promise of this line of inquiry. Her investigation of the lineages of this order makes it evident that it was also a tactical move in a larger strategic plan to assert executive branch power over Congress and the courts, and to curtail due process protections. The best and deepest investigative reporting, in the tradition of I. F. Stone, has always followed Greenhouse’s model. What is so valuable here is that she has theorized the practice so well as to make it clear how high the stakes are in discursive analysis of this kind. If it were up to me, I would make her analysis required reading for the handful of reporters who take their jobs seriously.

During May 6, 2012 Jane’s Walk in Long Branch (Toronto), Mike James speaks at Parkview School at site of Colonel Samuel Smith’s cabin, built in 1797. Several years of organizing Jane’s Walks has enabled us to learn many new things about local history. Jaan Pill photo

Changes in world media ecosystem since 9/11

Scott’s reference to investigative reporting brings to mind how drastically the media ecosystem has changed with advent of the internet. Sources of interest in this regard include “The Flooded Zone: How We Became More Vulnerable to Disinformation in the Digital Era” – Chapter 3 by Paul Starr from The Disinformation Age (2020).

An excerpt reads:

Compared to the patterns in the mid-twentieth century, the news media and their audiences have been reconfigured along political lines. Americans used to receive news and opinion from national media – broadcast networks, wire services, and newsmagazines – that stayed close to the center and generally marginalized radical views on both the right and the left. Now the old gatekeepers have lost that power to regulate and exclude, and news audiences have split. By opening up the public sphere to a broader variety of perspectives, including once-shunned radical positions, the new environment should have advanced democratic interests. But the forms of communication have aggravated polarization and mutual hostility and the spread of disinformation.

Recently I came across an April 7, 2025 New Yorker article by Nikil Saval entitled: “James C. Scott and the Art of Resistance: The late political scientist enjoined readers to look for opposition to authoritarian states not in revolutionary vanguards but in acts of quiet disobedience.”

It’s of interest to read such a comprehensive, wide ranging overview. I look forward to reading In Praise of Floods (2026).