The Drug Wars in America, 1940-1973 (Kathleen J. Frydl, 2013)

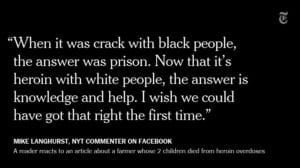

The image – click on it to enlarge it – is from a March 18, 2017 tweet from The New York Times @nytimes reading: Our top 10 comments of the week http://nyti.ms/2nD8BJX

Around the time that it was published, I read a book by Charles Tart entitled Altered States of Consciousness: A Book of Readings (1969).

The book introduced me to a concept that I found appealing.

In the book, Charles Tart or some other writer asserts that if one wants to enhance one’s level of consciousness, engaging in a systematic way in practices such as meditation is more likely to produce favourable results than dabbling with psychedelic substances.

The concept had a strong impact on my efforts to make sense of reality.

I personally don’t see much value in recreational drug use, but I do believe people should be free to indulge in such activities without the risking of a criminal record and incarceration.

I’m reminded, in this context, of an August 5, 2013 opinion article in Vancouver 24 Hours entitled “Time to get off the pot on marijuana laws.”

Marijuana laws

The article – which you can access through the link in the previous sentence – is prefaced with a quotation:

- Penalties against possession of a drug should not be more damaging to an individual than the use of the drug itself; and where they are they should be changed. Nowhere is this more clear than in the laws against possession of marijuana in private for personal use. — ex-U.S. president Jimmy Carter, August 1977

The opening paragraphs of the article read:

“It simply makes no sense that thousands of British Columbians face a criminal record each year for simple possession of marijuana.

“And it’s even crazier that the number of cannabis drug offences reported by police in B.C. jumped to 16,578 in 2011, up from 11,952 in 2002.

“These B.C. government statistics mean that even as marijuana has become increasingly socially acceptable, more people are being arrested in this province, charged with cannabis possession offences and getting criminal records.”

You can read the full article here.

I began this post with the intention of writing about a 2013 study by Kathleen J. Frydl. This is a fascinating book; I’m very pleased I came across it.

The Drug Wars in America, 1940-1973

The book begins with a quotation from John Kenneth Galbraith:

- Power obviously presents awkward problems for a community which abhors its existence, disavows its possession, but values its exercise. — John Kenneth Galbraith, American Capitalism: The Concept of Countervailing Power (Cambridge: Riverside Press, 1952), 26

The title of Frydl’s book reminds me of military history and the many kinds of wars that have occurred in the course of history.

In getting acquainted with this book, I was also captivated by a footnote regarding James Q. Wilson’s body of work, which I will share below.

War on Drugs, War on Terror, War on Nature

I’ve discussed the concept of war as work in a previous post.

War is also frequently spoken of figuratively or metaphorically, as in War on Nature; War on Drugs; War on Poverty; War on Terror; and war of words.

By themselves, with regard to the study of history, such figures of speech don’t have much meaning.

In order for a given formulation related to warfare to have meaning, I would argue that certain conditions must be met.

These include the availability of verifiable evidence, and a suitable frame of reference by which to analyze it. Frydl’s study aptly meets these requirements.

War is work by other means

In Soldaten (2011), Sönke Neitzel and Harald Welzer have focused upon a formulation that can broadly be stated as: War is work by other means.

In the context of the analysis by Sönke Neitzel, a historian, and Harald Welzer, a social psychologist, the concept of war as a job serves as an interpretive paradigm.

The authors note, in this context, that interpretive paradigms are especially central to how soldiers in the Second World War experienced their day to day lives:

“Paradigms equip frames of reference with prefabricated interpretations from different social contexts that are imported into the experience of war. This is especially significant for the notion of ‘war as a job,’ which in turn is extremely important for soldiers’ interpretations of what they do” (p. 18).

Such a formulation is one destination where the evidence may lead us, in the event that we wish to include the available evidence when we engage in discussion about the meaning of warfare.

Generally speaking, when a person eschews evidence-based practice, she or he travels into the borderland between fact and fiction, as an August 2, 2013 New Yorker article illustrates.

War is work that soldiers do; who are the workers in the Drug Wars?

In the Wars on Drugs, who are the workers? I would say that the foot soldiers are the narcotics agents and police services. They are employed and get paid so long as the drug wars continue. Drug wholesalers and distributors similarly are at work so long as the state of warfare – or more specifically, the network of conditions that give rise to such wars – continues.

The War on Terror has many players including specialists in organized violence who find steady work on all sides of contemporary global conflicts. The War on Nature involves pretty well all of us, and always has.

James Q. Wilson

The following footnote, on p. 14 of Frydl’s study, caught my attention as it covers much ground in a limited number of words:

- While assessments of James Q. Wilson’s body of work have been monopolized by his “broken windows” theory on how disorder attracts crime, much of the rest of his scholarship – including, especially, The Investigators and Bureaucracy – comprises the extent to which any scholar has attempted to assess conservative state-building across various domains as part of the modern government enterprise. See Wilson, Bureaucracy: What Government Agencies Do and Why They Do it (New York: Basic Books, 1989); The Investigators: Managing FBI and Narcotics Agents (New York: Basic Books, 1978).

Argument is advanced that effective control of illicit traffic and consumption were never the critical factors

As Marshall McLuhan aptly commented, the future of the book is the blurb.

The blurb at the Toronto Public Library website shares the following blurb regarding Drug Wars in America, 1940-1973 (2013):

- The Drug Wars in America, 1940-1973 argues that the U.S. government has clung to its militant drug war, despite its obvious failures, because effective control of illicit traffic and consumption were never the critical factors motivating its adoption in the first place. Instead, Kathleen J. Frydl shows that the shift from regulating illicit drugs through taxes and tariffs to criminalizing the drug trade developed from, and was marked by, other dilemmas of governance in an age of vastly expanding state power. Most believe the “drug war” was inaugurated by President Richard Nixon’s declaration of a war on drugs in 1971, but in fact his announcement heralded changes that had taken place in the two decades prior. Frydl examines this critical interval of time between regulation and prohibition, demonstrating that the war on drugs advanced certain state agendas, such as policing inner cities or exercising power abroad. Although this refashioned approach mechanically solved some vexing problems of state power, it endowed the country with a cumbersome and costly “war” that drains resources and degrades important aspects of the American legal and political tradition.

Addiction

We can add that drugs come in many forms, giving rise to a wide range of responses, as an April 30, 2013 article in Maisonneuve Magazine underlines. The article is among the links that I’ve listed in an earlier post regarding Total Institutions, of which prisons in North America serve as exemplars.

A July 24, 2014 New Yorker article notes that prescription medications now kill more people than heroin and cocaine combined. The article is entitled: “Who’s afraid of Zohydro?”

Updates

An Aug. 11, 2014 New Yorker article, which features Alice Goffman’s work, is entitled: “The Crooked Ladder: The criminal’s guide to upward mobility.”

An Aug. 22, 2014 CBC article is entitled: “Painkillers prescribed chronically to many Americans on disability. ” The subtitle reads: “Effectiveness of narcotic painkillers like OxyContin ‘at best uncertain, and the risks are very real'”.

A Dec. 9, 2014 CBC article is entitled: “Decriminalize cocaine and psychedelics, global group. urges: Commission of ex-world leaders, activists claims more human approach would be fiscally prudent.”

A Sept. 12, 2014 Globe and Mail article is entitled: “High-dose opioid prescribing rising dramatically in Canada.”

A Feb. 4, 2015 Globe and Mail article is entitled: “Researchers link common over-the-counter drugs to dementia.”

A May 10, 2015 New York Times article is entitled: “The Real Problem With America’s Inner Cities.”

Click here to access excerpts from the latter article >

A May 15, 2015 New York Times article is entitled: “Latin American Allies Resist U.S. Strategy in Drug Fight.”

A July 30, 2015 New York Times article is entitled: “Who Runs the Streets of New Orleans? How a rich entrepreneur persuaded the city to let him create his own high-tech police force.”

A Dec. 19, 2015 Guardian article is entitled: “Fatal drug overdoses hit record high in US, government figures show.”

A Jan. 15, 2016 New York Times article is entitled: “Why Cartels Are Killing Mexico’s Mayors.”

A Feb. 22, 2016 New York Tims article is entitled: “For Mark Willenbring, Substance Abuse Treatment Begins With Research.”

An Aug. 2, 2016 Stat article ie entitled: “Dope Sick: A harrowing story of best friends, addiction — and a stealth killer.”

An Aug. 22, 2016 CBC article is entitled: “Fentanyl found at Prince’s estate mislabelled as weaker opioid: Prince had no prescription for controlled substances in Minnesota in the 12 months before he died.”

An Aug. 23, 2016 Daily Hampshire Gazette article is entitled: “Student athletes cautioned on opioid medication.”

An Aug. 24, 2016 Vancouver Sun article is entitled: “Doctors ‘waking up’ to opioid over-prescription problem in Canada: CMPA [Canadian Medical Protective Association].”

An Aug. 25, 2016 Independent (U.K.} article is entitled: “Illegal drugs are changing the basis of the food chain in rivers: ‘As society continues to grapple with aging wastewater infrastructure and escalating pharmaceutical and illicit drug use, we need to consider collateral damages to our freshwater resources’”.

An Aug. 29, 2016 New Yorker article is entitled: “A Drawdown in the War of Drugs: The President’s commuting of sentences and an end of the use of private prisons signal potentially meaningful changes in how the United States handles drug abuse.”

A Sept. 6, 2016 Brookings Institution article is entitled: “Detoxifying Duterte’s drug directives.”

Also of interest and relevance: White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide (2016)

As well: Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (2016)

As well, a useful, evidence-based resource is entitled: Cochrane Handbook of Alcohol and Drug Misuse (2012).

An April 8, 2017 Washington Post article is entitled: “How Jeff Sessions wants to bring back the war on drugs.”

Also of interest: Blitzed: Drugs in Nazi Germany (2016).

A blurb reads:

‘The most brilliant and fascinating book I have read in my entire life’ Dan Snow

‘A huge contribution… remarkable’ Antony Beevor, BBC RADIO 4

‘Extremely interesting … a serious piece of scholarship, very well researched’ Ian Kershaw

The sensational German bestseller on the overwhelming role of drug-taking in the Third Reich, from Hitler to housewives.

The Nazis presented themselves as warriors against moral degeneracy. Yet, as Norman Ohler’s gripping bestseller reveals, the entire Third Reich was permeated with drugs: cocaine, heroin, morphine and, most of all, methamphetamines, or crystal meth, used by everyone from factory workers to housewives, and crucial to troops’ resilience – even partly explaining German victory in 1940.

The promiscuous use of drugs at the very highest levels also impaired and confused decision-making, with Hitler and his entourage taking refuge in potentially lethal cocktails of stimulants administered by the physician Dr Morell as the war turned against Germany. While drugs cannot on their own explain the events of the Second World War or its outcome, Ohler shows, they change our understanding of it. Blitzed forms a crucial missing piece of the story.

[End of text]