Across from the Sun Life Building in Montreal stands an early 1900s Boer War monument commemorating several British empire ‘war stories’

This blog post can be accessed as a PDF file:

Across from the Sun Life Building in Montreal

*

View from Royal Victoria College, Montreal, May 2022. Jaan Pill photo

In May 2022, after an absence of many years, I visited downtown Montreal for several days. I stayed at Royal Victoria College. One day during the visit I walked over to Dorchester Square across from the Sun Life Building which is where my mother worked for many years starting in the 1950s. At the square, I had a close look at a British empire monument – which prompted me to think, in turn, about what I’ve learned over the past dozen years about the history of the British empire.

I began to read about the British empire because I wanted to know more about a British colonel who in 1797 had built a log cabin, the archaeological remains of which were located a one-minute walk from our house in Long Branch, Toronto where we lived for twenty-one years from 1997 until 2018, when we moved to Stratford, Ontario.

The historical record offers few details about the colonel – and, certainly, no one has managed to put him on a pedestal. Given this state of affairs, it occurred to me that I would be able to learn something, at least, by picturing his life and times by reading about the history of the British empire. When I began this study, out of curiosity about a British colonel – who was the original settler colonialist owner of all of what is now Long Branch, and a stretch of land that extended beyond Long Branch, as well – I had no idea what I would learn.

Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada

Both my parents worked when I was growing up in Cartierville in Montreal. My father worked as an estimator at a steel company in Ville St. Laurent. In Sweden after the Second World War, my father had worked for several years as a forestry surveyor having been educated in forestry at the University of Tartu in Estonia.

My mother was educated as a lawyer at the University of Tartu. In Canada where we arrived in 1951, she worked as a tax specialist at the Sun Life Building at Dorchester Square in Montreal. The building is opposite several monuments which are distributed across the square. When I was growing up, the square was known as Dominion Square.

Dorchester Square

An excerpt from an online page about Dorchester Square (also known in years past, as I understand, as Dominion Square Park) reads:

The Park describes the growth of a political and industrial era prior to Confederation and the growth of railway technology and transportation. The [P]ark sits over a series of railway lines and the five kilometer tunnel of Canadian National Rail. The varied monuments are dedicated to persons who fought for a unified state prior to Confederation.

The web page adds that “In 1967, the Square was divided into two parts; the north part was renamed Dorchester Park after Baron Dorchester who supported the French in British North America and the south part was renamed ‘Place du Canada’, after Canada celebrated its centennial anniversary.”

Broken milk bottle

My mother originally had been working at another workplace in downtown Montreal but one day a milk bottle at our front door in Cartierville happened to get broken. In those days, milk bottles were left at people’s doors by a milk-delivery service. She cleaned up the broken glass and was late for work; each day she travelled to work by train from Cartierville to Central Station in Montreal. On its way to downtown, the train travelled through a tunnel under Mt. Royal. When she arrived at work, her boss bawled her out for being late.

My mother had no use for being bawled out. If I remember the story correctly, she went the same day to look for another job and was offered a job at once at the Sun Life Assurance Company. In the early 1950s, jobs in Montreal were easy to come by.

When she told her boss that she’d found a new job, the boss was not pleased. In my mother’s account, the boss said, in paraphrase, “Why, I did you a big favour when I hired you, and that means I picked you up out of the gutter!” My mother wasn’t impressed by the comment. She worked at Sun Life for about twenty years. She told me once that as she rose up through the ranks at the company, she realized that, after a particular level was reached, by an unspoken rule women were not promoted any further.

Thomas Bassett Macaulay

Plaque in Dorchester Square dedicated to Thomas Bassett Macaulay (1860-1942) of the Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada. Jaan Pill photo

An Historic Sites and Monuments and Monuments Board of Canada and Canada Parks plaque (opposite the Sun Life Building) reads:

Thomas Bassett Macaulay (1860-1942)

From 1877 to 1934, Macaulay rose from clerk to president of the Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, playing a vital role in the creation of the modern life insurance industry in Canada. His policy innovations made coverage appealing and available to a broad range of clients. His bold investment strategies resulted in extensive Sun Life stock holdings, stimulating general economic growth. Through his many philanthropic efforts, this prominent businessman helped build strong communities. He applied the same talent for innovation to his Mount Victoria Farm, where he developed a new line of Holstein cattle.

Click here for a Canadian Encyclopedia article about Sun Life Financial >

Canadian Golfer, April 1923

An advertisement – which was inserted into the main text of the publication – for Sun Insurance in the April 1923 issue of Canadian Golfer (p. 901) reads:

A WELL-WORTH-WHILE POLICY

AGAIN this year the Sun Insurance office, the oldest Insurance Company in the world [sic], is issuing ‘‘The Golfer’s Policy,’’ which for the very small annual premium of $10 covers the fortunate holder against breakage of clubs; for $5,000 in respect of legal liability and law costs for the death or injury to persons of the public (including his caddie, club members and club employees), and in respect of damage to property or animals whilst playing golf on any golf course in Canada or the United States; a payment of $5,000 in case of death and $25 per week for temporary total disablement (for 26 weeks). Then in addition the policy guarantees $100 in respect of damage by fire or lightning to golf clubs, balls and golfing equipment (including golfing clothing), anywhere in Canada and the United States, save in the insured’s residence.

Last year the ‘‘Sun’’ paid breakage of club claims to members of almost all the principal clubs in Canada to the benefit of not only ‘‘dubs,” but even seasoned players. No less an expert than Mr. George S. Lyon was among those who was paid a claim in this respect.

The ‘‘Sun’s’’ policy is a most liberal one, and the “Canadian Golfer” unhesitatingly recommends it to the golfers of the Dominion. Apart from the breakage of clubs clause, the safeguarding against personal liability on the links, accident and fire makes it a most invaluable undertaking. Policies can be obtained from any agent or Branch of the Company or from the Head Office, Sun Building, Toronto.

Whether this was actually the “oldest Insurance Company in the world” is questionable. Such a statement would require verification; based on what I’ve learned from a quick online search, Sun Life is not in fact the oldest insurance company in the world:

Click here for an Investopedia account of the history of insurance >

However, if I’m in error about this, please let me know.

A significant contribution to the family income

I’m pleased my mother found work at Sun Life. The money my mother brought in contributed significantly to the family income. It’s always a great thing when a family has a roof over their head, has sufficient food to eat, and has a sense of security about their lives; such a state of affairs is beyond the grasp of some of us, some of the time.

During the German occupation of Estonia during the Second World War, my mother along with many other people in occupied countries became well acquainted with what it means when the prospect of starvation stares you in the face. People would be eating the bark off of trees. On occasion, she would talk about those years.

A strategy planned for the long term – and in many cases adopted in the near term – by Nazi Germany during the Second World War involved the intentional starvation of civilian populations. The intentional starvation of Indigenous peoples as a component of British, European, and American settler colonialist history is similarly well documented.

Many versions of history are available; each of us can choose the one that we find most appealing

Many resources are available if we choose to study the history of the British empire. A person can, in pursuit of an understanding of how things work in the world, choose whichever version or versions of the history of the empire appeals to them. I am pleased we were welcomed – with open arms, in our case – as immigrants arriving in Canada in 1951. I feel fortunate living in Canada. I feel at ease with the fact that in Canada a person has a certain degree of freedom, regarding how they choose to think about the country’s history.

Boer War monument

The current post is devoted to the Boer War monument located at Dorchester Square across from the Sun Life Building. An article about the monument on the Art Public – Ville de Montréal website reads:

The monument stands in the centre of Dorchester Square and faces north. It was financed by public subscription, and the subscription committee commissioned the artwork and chose the site.

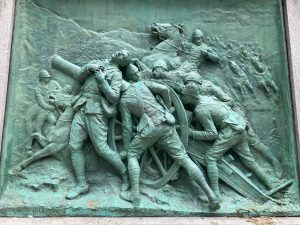

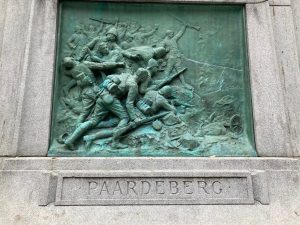

The monument is composed of a bronze equestrian statue placed on a parallelepiped grey-granite pedestal adorned with three bronze bas-reliefs and numerous inscriptions. Two of the bas-reliefs relate episodes in the war in which Canadian soldiers stood out: the battle of Paarleberg, in which the Boers surrendered to the Canadian infantry, and the battle of Komati River, in which the Canadian artillery seized the enemy’s guns. The third bas-relief is a portrait in profile of Lord Strathcona. The sculpture at the top presents a scout from Lord Strathcona’s Horse having dismounted, holding with his right hand the bridle of his frightened and rearing horse. The imposing equestrian group is one and a half times life size.

It is the only equestrian monument in Montréal and one of the few in Canada. It was also the first major commission that [George William] Hill produced. The architects Edward and William S. Maxwell designed the pedestal.

Associated events

The monument commemorates both the heroism of the soldiers who died on the field of honour and the involvement of Lord Strathcona (1820–1914), governor of the Hudson Bay Company. Strathcona equipped a cavalry regiment for Great Britain, on the occasion of Canada’s first participation in an overseas war, the Boer War, which pitted Great Britain against the Boers, the descendants of the first German, French, and Dutch settlers to arrive in South Africa in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. After the British victory, the Boer territories were annexed to the British Empire.

Click here for a previous post about the history of the Hudson’s Bay Company >

Hudson’s Bay Company

The reference to the Hudson’s Bay Company brings to mind a recent study, Empire Incorporated: The Corporations That Built British Colonialism (2023) by Philip J. Stern.

The British empire’s joint-stock companies such as the Hudson’s Bay and the East India Company played a central role in the financing and shaping of the empire. An excerpt from a book review by Caroline Elkins of Empire Incorporated (2023) in the September/October 2023 issue of Foreign Affairs reads:

What began in the ignominy at Amboyna would end in the creation of a globe-spanning empire and the modern world as we know it. The East India Company, arguably the most enduring public-private partnership in history, helped make the British Empire, fuel the industrialization of Europe, and knit together the global economy. It was chief among dozens of other chartered companies granted monopoly rights and sovereign claims through politically issued charters. These companies, the avatars of the crown, merged the pursuit of profit with the prerogatives of governance, although, much like the VOC [Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie – powerful Dutch monopoly trading company], they often governed as they pleased, without legally enforceable responsibilities. Importing raw materials, they fed the Industrial Revolution’s manufacturing sector, stimulated demand for foreign products, and dominated London’s burgeoning capital markets while also undertaking the state’s bidding in establishing the British Empire. Chartered companies helped claim nearly a third of the world’s territory for the United Kingdom, making its empire the largest ever known.

Scholars have long debated the significance and lingering impact of these imperial-era firms. Some analysts, focusing on profit and scale, see present-day corporate behemoths as contemporary manifestations of chartered companies. Others see the largest of them all, the East India Company, as even more powerful: one BBC writer saw it as “the CIA, the NSA, and the biggest, baddest multinational corporation on earth,” whose power, much like that of a company such as Meta, went virtually unchecked for years. Chartered companies often existed beyond the reach of state regulation and in many ways functioned as states in their own right, with their own forms of sovereignty. Their legacy extends to contemporary tensions between hefty multinational technology corporations and the countries that struggle to restrain them.

Philip Stern’s landmark book, Empire, Incorporated· The Corporations That Built British Colonialism, resists facile comparisons between today’s multinational corporate giants and the chartered companies of yesteryear. It traces the evolution over four centuries of the British Empire’s joint-stock corporations, the East India Company among them, and their role in the state’s imperial designs, what Stern calls “corporate colonialism.” Urging his readers to reflect “on the present quandaries of public and private power more through genealogy than analogy,” Stern painstakingly demonstrates how joint-stock “venture colonialism” financed and shaped the British Empire, forging legacies that endure to the present day.

Books which do a great job of addressing similar themes include Fire Weather: The Making of a Beast (2023) by John Vaillant; The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis (2021) by Amitav Ghosh; and The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company (2019) by William Dalrymple.

The book by John Vaillant underlines the reality that climate change – the history of which goes back to when the Hudson’s Bay Company reigned supreme – dominates the present moment. A Nov. 19, 2023 CTV News article highlights the current state of affairs. An excerpt from the article, entitled “Top 1 per cent wealthiest responsible for same amount of carbon emissions as bottom 66 per cent,” reads:

Global inequality and the climate crisis go hand in hand, the report argues.

Lord Strathcona (1820-1914) and Royal Victoria College

In May 2022, I stayed at Royal Victoria College which offers accommodations for tourists when McGill University classes are not in session. I recently learned of Lord Strathcona’s connection to the residence when I read an online resource which observes that

The origin of Royal Victoria College can be traced back to the Montreal Ladies’ Educational Association (see M.G. 1053) which had offered its members university-level lectures in various subjects between 1881 and 1884. Various McGill staff members such as John Clark Murray gave lectures in the arts and sciences, including philosophy and geology. In 1884, Donald A. Smith (later Lord Strathcona) started providing for women students to attend separate classes at McGill. Due to the same benefactor, Royal Victoria College opened in 1899 as a residential college for women at McGill. In honour of Donald A. Smith, female students were known as “Donaldas” from 1884 to about 1914. Royal Victoria College admitted both resident and non-resident women. Until the 1970s all female undergraduates at McGill were also members of R.V.C. The College’s chief function is now that of a residence and much of the original building on Sherbrooke and University Streets is occupied by the Faculty of Music.

150 Years of Military History in Downtown Montreal

Another online resource shares information about the setting in which the Boer War monument is positioned. An excerpt from an article, entitled “150 Years of Military History in Downtown Montreal” at the Government of Canada – National Defence website, reads:

Introduction

In Montreal at the turn of the 20th Century, multiple visions of Canada co-existed. Some citizens, mainly Anglophones, viewed Canada as a colony with a duty to contribute to the prestige of Great Britain. Others, mostly Francophones, saw it as an autonomous power within the British Empire. In the middle were the moderates, who wanted the two groups to get along and live together in harmony. Dorchester Square and Place du Canada are home to several commemorative monuments that illustrate those visions and, collectively, show how the site originally symbolized British power, but gradually came to reflect contemporary Canada and Montreal.

Origins of the site

In 1795, burial of corpses was prohibited within the fortifications of Montreal, so the Parish of Notre-Dame purchased land outside the city walls to use as a graveyard. Montreal’s dead were buried there until a new cemetery was opened on Côte-des-Neiges in 1854. Removal of the bodies from the original graveyard began, but serious public health concerns were raised, including fears of a cholera epidemic. The exhumations were stopped and the rest of the bodies were left in place; 10,000 of them still lie beneath downtown Montreal. In 1871, to beautify the area and encourage healthy recreation, the city fathers decided to create a public park on the site, to be named Dominion Square in honour of the 1867 Confederation of Canada.

The City decided to build the park within the same boundaries as the former cemetery. That explains the unique shape of the space: two rectangles, slightly offset, separated by René-Lévesque Boulevard. The ground is sloped, and the streets along its edges are irregular. Today, the northern section is called Dorchester Square; the southern section is Place du Canada.

From the time the park was opened, it has been associated with the military. The Fusiliers de Victoria brass band played concerts there. In addition, many military parades were held downtown, and all of them passed through the square. The idea of commemorating military heroes and victories was thus consistent with the identity of the site. In all, there are four elements commemorating military history at this location.

Royal Canadian Artillery, Canadian Montreal Rifles, Royal Canadian Infantry, and Strathcona Horse

A second excerpt from the web page reads:

The lower part of the [Boer War] monument is classical in design, with decorative elements, and resembles that of a typical cenotaph. At the four corners, the names of the Canadian regiments that participated in the conflict are inscribed: Royal Canadian Artillery, Canadian Montreal Rifles, Royal Canadian Infantry, and Strathcona Horse. An inscription on the west side of the monument reads as follows: “To commemorate the heroic devotion of the Canadians who fell in the South African war and the valour of their comrades.” The east side of the monument bears the inscription “In grateful recognition of the patriotism and public spirit shown by Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal in raising and equipping a regiment of horse for service in South Africa as an evidence of his sympathy with the cause of imperial unity.” On the south side is a list of the battles in which Canadian troops participated. Two hauts-reliefs depict heroic episodes: on the west side of the monument, the Battle of Paardeberg, where the Boers surrendered to the Canadian infantry, and on the east side, the Battle of Komati River–Belfast, where the Canadian artillery seized the enemy’s rifles. Lastly, on the north side of the monument there is a medallion of Lord Strathcona with his coat of arms.

In the early-20th Century, it was the most photographed statue in Montreal. Today, its dated style and its English-only inscriptions imprison the work in the past.

Two versions of the history of the British empire – Version One, David Cannadine (2001)

When I first began reading about the history of the British empire, I encountered a study by David Cannadine as I’ve outlined in an Aug. 5, 2012 post entitled:

Class and status drove the British empire, David Cannadine (2001) argues

An excerpt reads:

Concept of a vast interconnected world of imperial experience

In Ornamentalism (2001), Cannadine discusses previous books about the British empire.

One approach views the rise of the empire as the outcome of impulses originating in Britain. A first group of writers sees the impulses as primarily of an economic nature. A second group sees them in terms of military and strategic imperatives. A third group detects an altruistic impulse at play. A fourth group attends to law, governance, and constitutional evolution in imperial history. An alternative approach focuses on the imperial periphery, on the experiences of the peoples affected by the empire.

Cannadine prefers an approach that takes into account the ‘one vast interconnected world’ of the imperial experience. In that world, Britain was part of the empire, and the empire was a part of Britain: The metropolis influenced the periphery and was influenced by it.

Cannadine foregrounds class as key feature of imperial social structure

Ornamentalism (2001) focuses on how the British, at home and overseas, envisioned and imagined their imperial society. The author addresses the empire as social structure and social perceptions. The’s book intent, according to the author, was to understand the empire in a new and original way, as having been the vehicle for extension of Britain’s social structures and projection of British perceptions.

As in a previous book, Class in Britain (1998), Cannadine is concerned with a ‘layered, individualistic hierarchy,’ a model of British society that he asserts is more appealing and convincing than the two- or three-stage models of social structure – them versus us or upper-middle-lower class – adopted by others. He argues that to the extent that the British empire was a unified enterprise, it was driven by an effort to tie together the periphery in the image of the ranked social hierarchy of the metropolis.

He suggests, in that regard, that Britons saw themselves “as belonging to an unequal society characterized by a seamless web of layered gradations, which were hallowed by time and precedent, which were sanctioned by tradition and religion, and which extended the great chain of being from the monarch at the top to the humblest subject at the bottom” (Ornamentalism, 2001, p. 4).

Cannadine’s characterization of British imperial society has a mellifluous tone to it. Whether or not the characterization is apt, or whether the topic warrants the tone, is a question that naturally comes to mind.

In the hierarchical model to which he refers, both class and race are viewed as playing a role, but Cannadine generally foregrounds class as the predominant feature. With regard to race, by the end of the eighteenth century, British notions of racial hierarchy were exemplified in Cecil Rhode’s claim that “the British are the finest race in the world, and the more of the world they inhabit, the better it will be for mankind” (Ornamentalism, 2001, p. 5).

Starting with the British colonies on the eastern seaboard of North America, hierarchical attitudes and traditional preferences, both ethnic and social, including an attitude of contempt toward Indigenous non-white races, had been strongly in evidence from the beginning. A general hardening of attitudes toward colonial Indigenes subsequently found replication in the nineteen-century settlers in the four dominions of the empire including Canada.

Cannadine argues, however, that distinctions within the empire were not entirely related to a hierarchy of race. He notes that when the English first encountered the Native peoples of North America in the pre-Enlightenment sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, they did not see them collectively as an inferior race. Instead, the author asserts, they saw the latter societies as hierarchical societies not unlike their own.

He adds that Britons’ sense of hierarchy “was not exclusively based on collective, colour-coded rankings of social groups, but depended as much on the more venerable colour-blind ranking of individual social prestige.” That is the book’s central argument.

Two versions of the history of the British empire – Version Two, Caroline Elkins (2022)

A Oct. 18, 2022 post is entitled:

Caroline Elkins (2022) outlines the legacy of violence of the British empire

An excerpt reads:

The Kirkus Review article reads:

LEGACY OF VIOLENCE: A HISTORY OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE

by Caroline Elkins

A scathing indictment of the long and brutal history of British imperialism.

Historian Elkins, founding director of Harvard’s Center for African Studies and Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya (2005), frames her narrative with two events that actually took the British Empire to task for its violent imperial policy over centuries. The first was the 1788 impeachment trial of governor-general of India, Warren Hastings, during which Parliament demanded accountability for his repressive tactics, shocking the nation. The second is the 2011 case of the survivors of the Mau Mau rebellion. Throughout this tour de force of historical excavation, Elkins confronts the decidedly Western ideas of the social contract, government responsibility, and the importance of personal property alongside the enduring belief that White men alone could institute these marvelous liberal gifts. “When 19th century liberalism confronted distant places and ‘backward people’ bound by strange religions, hierarchies, and sentimental and dependent relationships, its universalistic claims withered,” writes the author. “[Britons] viewed their imperial center…as culturally distinct from their empire….Skin color became the mark of difference. Whites were at one end of civilization’s spectrum, Blacks at the other. All of shades of humanity fell somewhere in between.” Paternalistic attitudes continued to evolve across the empire, and Elkins provides especially keen examinations of colonies where clashes were particularly forceful and “legalized lawlessness” was widespread – among other regions, India, South Africa, Palestine, Ireland, Malay, and Kenya. Offering numerous correctives to Whitewashed history, the author mounts potent attacks against the egregious actions of vaunted figures like Winston Churchill; Henry Gurney, commissioner of Malay; and Terence Gavaghan, a colonial officer in Kenya. Over the course of the 20th century, Britain was forced to cede many of its sovereign claims to empire, at enormous human cost. Elkins masterfully encapsulates hundreds of years of history, amply showing how “Britain was to the modern world what the Romans and Greeks were to the ancient one.”

Top-shelf history offering tremendous acknowledgement of past systemic abuses.

Caroline Elkins’s earlier research focused on the crushing of Mau Mau uprising in Kenya

My own preference is the version of the history of the British empire that Elkins presents based on her cogently articulated and thorough research. And, I say this with the understanding that the legacy of violence in the British empire which Elkins documents came in very handy in the course of Britain’s significant contribution to the outcome of the Second World War. I also want to say that I fully support George Orwell’s views regarding political stances that make sense as contrasted to those which are to be abhorred, as I outline below.

An evocative Aug. 18, 2016 Guardian article – about earlier research by Elkins – is entitled: “Uncovering the brutal truth about the British empire: The Harvard historian Caroline Elkins stirred controversy with her work on the crushing of the Mau Mau uprising. But it laid the ground for a legal case that has transformed our view of Britain’s past.”

An excerpt reads:

The Mau Mau uprising had long fascinated scholars. It was an armed rebellion launched by the Kikuyu, who had lost land during colonisation. Its adherents mounted gruesome attacks on white settlers and fellow Kikuyu who collaborated with the British administration. Colonial authorities portrayed Mau Mau as a descent into savagery, turning its fighters into “the face of international terrorism in the 1950s”, as one scholar puts it.

The British, declaring a state of emergency in October 1952, proceeded to attack the movement along two tracks. They waged a forest war against 20,000 Mau Mau fighters, and, with African allies, also targeted a bigger civilian enemy: roughly 1.5 million Kikuyu thought to have proclaimed their allegiance to the Mau Mau campaign for land and freedom. That fight took place in a system of detention camps.

Elkins enrolled in Harvard’s history PhD programme knowing she wanted to study those camps. An initial sifting of the official records conveyed a sense that these had been sites of rehabilitation, not punishment, with civics and home-craft classes meant to instruct the detainees to be good citizens. Incidents of violence against prisoners were described as isolated events. When Elkins presented her dissertation proposal in 1997, its premise was “the success of Britain’s civilising mission in the detention camps of Kenya”.

But that thesis crumbled as Elkins dug into her research. She met a former colonial official, Terence Gavaghan, who had been in charge of rehabilitation at a group of detention camps on Kenya’s Mwea Plain. Even in his 70s, he was a formidable figure: well over six feet tall, with an Adonis-like physique and piercing blue eyes. Elkins, questioning him in London, found him creepy and defensive. He denied violence she hadn’t asked about.

“What’s a nice young lady like you working on a topic like this for?” he asked Elkins, as she recalled the conversation years later. “I’m from New Jersey,” she answered. “We’re a different breed. We’re a little tougher. So I can handle this – don’t worry.”

In the British and Kenyan archives, meanwhile, Elkins encountered another oddity. Many documents relating to the detention camps were either absent or still classified as confidential 50 years after the war. She discovered that the British had torched documents before their 1963 withdrawal from Kenya. The scale of the cleansing had been enormous. For example, three departments had maintained files for each of the reported 80,000 detainees. At a minimum, there should have been 240,000 files in the archives. She found a few hundred.

But some important records escaped the purges. One day in the spring of 1998, after months of often frustrating searches, she discovered a baby-blue folder that would become central to both her book and the Mau Mau lawsuit. Stamped “secret”, it revealed a system for breaking recalcitrant detainees by isolating them, torturing them and forcing them to work. This was called the “dilution technique”. Britain’s Colonial Office had endorsed it. And, as Elkins would eventually learn, Gavaghan had developed the technique and put it into practice.

George Orwell

In speaking in favour of Elkins’s view of the history of the British empire I wish to affirm that I am aligned with a point of view – regarding certain extreme political orientations, and the destruction and mayhem inevitably associated with them – enunciated very effectively by George Orwell. In a recent post I have commented:

After reading about Orwell recently, I have a much better understanding of the distinction between the far left and left. In particular, Why Orwell Matters (2002) by Christopher Hitchens outlines the distinction in a way that I’ve found easy to follow. Hitchens addresses the distinction in Chapter 2, “Orwell and the Left” – and elsewhere in the book as well. [1]

Why Orwell Matters (2002)

An excerpt from Chapter 1, “Orwell and Empire” p. 34) in Why Orwell Matters (2002) reads::

It might not be too much to say that the clarity and courage of Orwell’s prose, which made him so readily translatable for Poles and Ukrainians, also played a part in making English a non-imperial lingua franca. In any event, his writings on colonialism are an indissoluble part of his lifelong engagement with the subjects of power and cruelty and force, and the crude yet subtle relationship between the dominator and the dominated. Since one of the great developments of his time and ours is the gradual emancipation of the formerly colonized world, and its increasing presence through migration and exile in the lands of the ‘West’, Orwell can be read as one of the founders of the discipline of post-colonialism, as well as one of the literary registers of the historic transition of Britain from an imperial and monochrome (and paradoxically insular) society to a multicultural and multi-ethnic one.

Viewpoint of Neil MacGregor, the former director of British Museum

I’ve also recently re-read an evocative Oct. 7, 2016 Guardian article entitled: “Britain’s view of its history ‘dangerous’, says former museum director: Neil MacGregor, once of British Museum, says Britain has focus on ‘sunny side’ rather than German-like appraisal of past.”

An excerpt reads:

Neil MacGregor, the former director of the British Museum, has bemoaned Britain’s narrow view of its own history, calling it “dangerous and regrettable” for focusing almost exclusively on the “sunny side”.

Speaking before the Berlin opening of his highly popular exhibition Germany – Memories of a Nation, MacGregor expressed his admiration for Germany’s rigorous appraisal of its history which he said could not be more different to that of Britain.

MacGregor is author of Germany: Memories of a Nation (2014).

Excerpts from Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire (2022)

The following excerpts are from the e-book version of Legacy of Violence (2022). Because they are from the e-book version, I do not have the page numbers at hand; the page numbers are omitted.

An excerpt from chapter 2 reads:

The Nobel laureate’s writings also countenanced methods of governance that inscribed racial and cultural differences. These differences became institutionalized at every level of executive, legislative, and judicial rule. [50] As British imperial claims transformed into formal colonial rule, the colonial state – whether early on in India with the emergence of the Raj in 1858, or later with the acquisitions of colonies and territories in Africa and the Middle East – was a far cry from the emerging modem nation states of Europe. Empires did not rule their subjects through consent. Instead, in the case of Britain, officials’ overriding presumption was that indigenous populations were neither capable of ruling themselves, nor effective at tilling their own land, nor respectful or comprehending of the authority of the colonial state without it having recourse to exceptional powers. If forms of colonial rule on the ground were intimately tied to forms of racial and cultural difference, so too were they bound to the realpolitik of Britain’s economic landscape. [51] As far as the British were concerned, an unwritten rule of empire, that colonies should be fiscally self-sufficient, was inviolable. Indeed, formal imperialism was expensive, and not all colonies were profitable. Like the rest of the empire, they had to generate revenue for local governing expenses, and colonial subjects paid for their repression in the form of taxes, cheap labor, and in some cases, land expropriation. [52]

A second excerpt from chapter 2 reads:

Regardless, co-opted local elites who, in the words of historian Frederick Cooper, facilitated Britain’s “dirty work,” were crucial to the empire’s functioning, as they were front and center in tax collecting, compelling subject populations into the labor market for pittance wages, and imposing communal forced labor projects, among other measures. [66] Incorporated into the colonial bureaucracy, they became part of the colonial project that institutionalized difference not only between colonizer and colonized but also between and among subject populations, sowing discord and civil conflict by accentuating ethnic and religious differences and rendering them politically and economically salient. This method of colonial governance – divide and rule – fed Britain’s need for on-the-ground indigenous agents. There was much about colonial rule, however, that was not indirect. The state, for instance, did not divest to these indigenous agents its monopoly over violence; nor did it divest the adjudication of crimes that violated the colonial-imposed social contract or decision making when it came to the colonial economy or suspending ordinary law and deploying security forces to quash dissent.

British power in the empire was limited in certain respects. Liberal imperialism did not translate into all-out repression at all times in all places. Nor did it fully penetrate indigenous social and cultural forms, creativity, responses to markets, or political activities – something the British would learn all too well in the twentieth century, as local populations continued to mount armed responses, big and small, to imperial rule. However, the empire’s capacity to destroy while ostensibly reforming was extraordinary. Economic and political self-interests combined with Kiplingesque concepts of civilization to drive British imperial decision making, ushering in forced economic dependencies, rural immiseration, urban disorder, famine, civil conflict, and unaccountability to subjects. At the same time, reform efforts, including the introduction of new education systems and public health measures, initially through missionary efforts and later through state-sponsored welfare departments and programs, were enacted side by side with policies, like forced labor, that through their harshness were supposed to reform “backward natives,” much as stern measures were supposed to advance children to adulthood.

Author’s note – Legacy of Violence (2022)

Author’s Note

This book contains derogatory words and phrases, quoted from historical actors, that refer to racial, ethnic, and religious groups. They are offensive. I have chosen to use these words and phrases, in their original forms, because this language represents the attitudes of some historical actors during this period and encodes much of the state-directed violence that I discuss and analyze.

Note 1

I highly recommend Why Orwell Matters (2002) by Christopher Hitchens along with other books by and about George Orwell. A list of good resources includes:

List of books and other resources about Orwell – Stratford Public Library

List of books and other resources about Orwell at Toronto Public Library

George Orwell, 1903-1950 – Toronto Public Library (a more concise list)

George Orwell – Criticism & Interpretation – Toronto Public Library

Why Orwell Matters (2002)

Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell’s Invisible Life (2023)

Orwell’s Roses (2021)

George Orwell, 1903-1950 – Homes and haunts – Toronto Public Library

Background on Russia and Ukraine – Toronto Public Library

George Orwell and Russia (2023)