In the early 1900s, Amsterdam conservationists helped preserve the city’s remaining canals; however, by then, its much-admired maritime vista had disappeared – thanks to a new railroad station

In a study entitled The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century (2014), Jürgen Osterhammel discusses what the arrival of the railroad meant for cities around the world, including for Amsterdam.

I have an interest in the history of Amsterdam following a visit to that city in August 2018, when I was taken with its bicycle-friendly transportation system, a system whose history I’ve been reading about ever since.

I have learned, for example, that a large number of traffic fatalities involving cars, in the early 1970s, including deaths of many children, sparked a wave of protests and activism that gave rise to construction, in subsequent years, of the city’s well-designed, highly effective bicycle infrastructure.

I have an interest, as well, in the role that railroads have played in the history of cities such as Stratford, Ontario, where I live – and of cities elsewhere, including Amsterdam.

In Stratford, a referendum in the early 1900s kept a railroad line from being built along the southern banks of the Avon River, which runs through the centre of Stratford, thereby ensuring that a system of parks remains in place to this day, at the heart of the city.

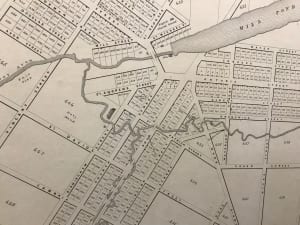

Detail from 1848 map of Stratford, on display at Stratford-Perth Museum. Portions of land north and south of the Mill Pond (now called Lake Victoria or simply the Avon River) were included in the park system as the city grew. The Stratford Theatre was built along the southern portion of parkland in 1952.

A Stratford builder named R. Thomas Orr played a key role in development of the city’s extensive park system – and in keeping the proposed railway line from being built.

The park system, in turn, served as an ideal venue for the launch, in 1953, of the Stratford Festival – at the Festival Theatre, which is centrally located within Stratford’s park system by the Avon River.

Construction of the theatre began in 1952, originally as a concrete amphitheatre which, in early years before a permanent roof was built, was covered by a huge, custom-built tent.

What did arrival of railroad mean, to a city?

Jürgen Osterhammel (2014) outlines the history of the railroad, viewed from a global perspective, as it relates in particular to the nineteenth century.

The author comments (p. 301):

What did the arrival of the railroad mean for a city? Everywhere, the early “railroad manias” not only involved money and technology but also affected the future shape of cities. Heated debates broke out over the relationship between private interests and public utility, and over the location and design of stations.

Placement of station changed whole character of Amsterdam, from a city by the sea to an inland city

Osterhammel notes, as well (pp. 301-2 of his 2014 study):

Railroad stations altered cityscapes: they could sometimes revolutionize the whole character of a city. The main station in Amsterdam, which opened in 1889, was built on three artificial islands and a total of 8,687 piles, driving a huge wedge between the inner city and the harbor front. The much-admired contrast between the cramped city and the open maritime vista disappeared, and Amsterdam changed in its perceptions and lifestyle from a city by the sea to an inland city. At the same time, one canal after another – sixteen in all – were filled in. The aim of the planners was to “modernize” Amsterdam, to make it conform to the model of other metropolises. Only protests by local conservationists ensured that the canal destruction came to an end in 1901, so that Amsterdam was able to keep at least its basic early modern design. [219]

Osterhammel’s bibliographical note (219), in the above-quoted text, refers to pp. 206-10 of a study by Geert Mak, entitled: Amsterdam: A Brief Life of the City (2001), which I will discuss at the conclusion of this essay.

Differing views, regarding meaning of life, as experienced at the local level

I have also been reading Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (1998), by James C. Scott. The latter study, which focuses on aspects of history of the twentieth century, serves as a good complement to Osterhammel’s study of the nineteenth century.

Osterhammel, a historian, makes it clear in his introduction to The Transformation of the World (2014) that he is a follower of a school of sociology that is convinced that the local doesn’t much matter, because, as he sees it, all of life’s experiences lead to a global perspective – in his view, as I gather, the only one that matters.

In contrast, James C. Scott (whom Osterhammel describes (p. 369) as a sociologist, but who in fact is a political scientist and anthropologist), in Seeing Like a State (1998), argues that when that which is the local is ignored by nation-state actors, by decision makers operating at the higher reaches of a society’s power structure, disaster awaits around the corner.

His book outlines a series of such disasters, in some cases leading to enormous destruction and deaths of millions, in the course of the twentieth century.

Osterhammel shares valuable overviews of nineteenth-century global history, but falls short with regard to the local-versus-global issue. That said, the relationship between history and social science is a matter of interest, and a topic worth pursuing, as I have noted at previous posts regarding the historian Peter Burke’s study of the relationship between history and social theory.

James C. Scott covers the local/global dichotomy more adroitly than Osterhammel, but, as he himself notes, the lens that he brings to his own study of history would not provide a suitable means, for making sense of absolutely everything.

I have made a point of reading both authors, because their contrasting approaches complement each other well. My preference remains, however, for the view of things that James C. Scott adopts.

By way of example, the revolutionary changes that have occurred, at the local level in the Dutch countryside outside of Amsterdam, over the past century, are more fully comprehensible, when viewed through the lens that Scott provides, than it is through the lens that Osterhammel’s historiography employs, valuable as it otherwise may be.

In its milder, less lethal, but nonetheless pernicious, forms, “seeing like a state” remains a pervasive mindset of modern life – as evidenced, for example, by changes in agriculture over the past century, in countries around the world.

Silent rural revolution in countryside outside of Amsterdam

As well as a book about Amsterdam among other works of non-fiction, Geert Mak is author of An Island in Time: The Biography of a Village (2010).

In the latter study, Mak addresses the history of his childhood home in the Dutch countryside, the small Frisian village of Jorwert (population 330 and falling).

An excerpt from a back-cover blurb for An Island in Time (2010) notes, regarding Jorwert:

It’s a typical European village where the shops are closing down, the few children left will escape to a less arduous life in the city and it’s becoming increasingly isolated. Jorwert has more in common with an English village than with Amsterdam, and its moving story of neighbours and their efforts to preserve their long-established way of life is relevant to the changing face of the countryside everywhere in Europe.

Geert Mak describes Amsterdam’s “greatest planning blunder ever”

Because he has more space to cover the topic at hand – that is, four pages, as contrasted to the one paragraph that Jürgen Osterhammel has available – Geert Mak is able to describe the consequences on the character of Amsterdam, of the building of the central railroad station, in more detail.

In the event you have an interest in the full description, I strongly recommend the reading of pp. 206-10 of Mak’s book about Amsterdam.

The following paragraph – one of a total of eleven paragraphs devoted to the “planning blunder” and related topics – from p. 207 of his book, offers a sense of how Geert Mak proceeds, with his masterful description:

The building of the Central Station was the largest construction project in nineteenth-century Amsterdam, and the city’s greatest planning blunder ever. Originally the plan had been to site the main station either in the vicinity of the Leidseplein or by the Weesperpoortstation, today’s Weesperplein. But the authorities in The Hague were convinced that the best place was right in front of the city, erected on three artificial islands. Almost all Amsterdam’s own experts and others involved thought this to be a catastrophic plan, “the most disgusting possible attack on the beauty and glory of the capital”. Nevertheless, the building of the Central Station in front of the open harbour was forced through by the railway department of the Ministry of Transport in The Hague, and the Home Secretary, Thorbecke. Finally, the plan made its way through the Amsterdam municipal council by a narrow majority.

Updates

An Aug. 19, 2019 BBC article is entitled: “What’s it like to live in an over-touristed city? Locals explain how the influx of travellers has affected them, how authorities are responding and how visitors can remain respectful of people who live there year-round.”

Tulip scam

An Oct. 16, 2019 CBC article is entitled: “Massive tulip scam uncovered in Dutch flower markets, says growers’: Just 1 per cent of bulbs flowered from Amsterdam flower market, investigation finds.”

An excerpt reads:

The investigated markets are visited by millions of tourists each year, and Hoogendijk said complaints about the bulbs go back as far as 20 years.

“[Tourists] go home, most of them don’t complain, and if they complain they don’t know where to go,” Hoogendijk said. “So they send out an email or something else but they don’t go back to the market and ask for money back, [and] that’s why these market vendors have been able to keep doing this for years now.”

Climate change

A Dec. 16, 2019 Politico article is entitled: “When will the Netherlands disappear? The low-lying country has centuries of experience managing water. Now climate change is threatening to flood it completely.”

An excerpt reads:

“With unprecedented sea level rise forecast as a result of climate change, the Dutch government is racing against the clock to figure out how to keep one of the world’s richest countries from disappearing into the North Sea.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!