Ambiguous figures can serve as heuristic device for study of social construction of meaning

I have an interest in the question of whether it may be possible to metaphorically represent the underlying processes driving the social construction of meaning.

In seeking an answer to the question, I have turned to visual configurations from the class of optical illusions known as ambiguous figures.

It may be noted that The Illusions Index website offers a useful overview of optical illusions of all kinds.

When we deal with ambiguous figures, specified cues can be introduced, whereby a viewer is prompted to resolve an ambiguous situation – consistently in a particular direction – under conditions where a binary choice between potential readings is inevitably required in keeping with how the brain is wired.

The latter phenomenon – the consistent response to ambiguity, resulting from dependence on a specified set of cues – can serve as a paradigm for how a strongly held belief system of any kind, whether it’s tethered to evidence (however defined) or untethered from it, appears to operate.

Underlying grid, on which current study of figure-ground transformations is based. Source: Jaan Pill, December 2019

Such a paradigm can serve to represent, for example, the transformation under specified conditions of anger at economic stagnation and wealth concentration into populism, authoritarianism, polarization, and totalitarianism.

Such a paradigm can also serve to represent processes whereby collaboration drives problem solving and innovation in response to pressing concerns such as extreme income inequality and climate change.

The paradigm is also applicable, among other things, to study of bias in the publication, for example, of medical evidence, or in relation to James C. Scott’s concept of seeing like a state.

Ambiguous figures and the like are also explored in mathematical realms such as Homology, Cohomology, and Sheaf Cohomology.

Visual storytelling

Among many other ways, the relationship between illusion and perception can be explored at the level of visual storytelling – at the level, that is, of data visualization in a context where data is largely qualitative, and at the level where metaphor intersects with materiality.

We are dealing, in this context, with phenomena related to modularity, and the compartmentalization of experience.

When we are dealing with how we go about constructing sense, through the social construction of meaning, we are dealing with constellations and configurations of forces. What manifests at the level of persons and personalities appears to a large degree an expression, and outcome, of such forces.

Among many studies of interest, in relation to study of ambiguity in visual perception, I have recently come across Sleights of Mind: What the Neuroscience of Magic Reveals about Our Everyday Deceptions’ (2010). I would note, however, that the book’s reference to what neuroscience is inferred to indicate about the ‘absence of free will’ appears outdated.

Another book that relates to social construction of visual representation is Visual Explanations: Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative (1997).

In particular, Ch. 3, ‘Explaining magic: Pictorial obstructions and disinformation design’ (1997) has long held my attention.

The latter chapter notes that stage-magic techniques, when reversed, ‘reinforce strategies of presentations used by good teachers’ (p. 68). The chapter has influenced my own approach to communications.

An Aug. 3, 2008 Boston Globe article is entitled: “How magicians control your mind: Magic isn’t just a bag of tricks – it’s a finely-tuned technology for shaping what we see. Now researchers are extracting its lessons.”

The article notes that our model of how perception occurs has changed; according to a new model, “visual cognition is understood not as a camera but something more like a flashlight beam sweeping a twilit landscape. At any particular instant, we can only see detail and color in the small patch we are concentrating on. The rest we fill in through a combination of memory, prediction and a crude peripheral sight. We don’t take in our surroundings so much as actively and constantly construct them.”

The article adds:

Our picture of the world is kind of a virtual reality,” says Ronald A. Rensink, a professor of computer science and psychology at the University of British Columbia and coauthor of a paper on magic and psychology that will be published online this week in Trends in Cognitive Sciences. “It’s a form of intelligent hallucination.”

A 2010 article about visual perception by Ronald Rensink (see previous paragraph), entitled “Seeing Seeing,” can be accessed here.

Click here for publications by Ronald Rensink >

Comment regarding current study involving ambiguous figures

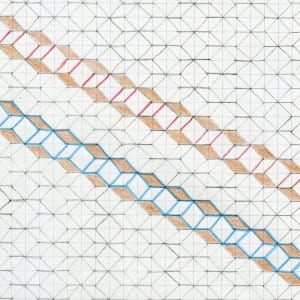

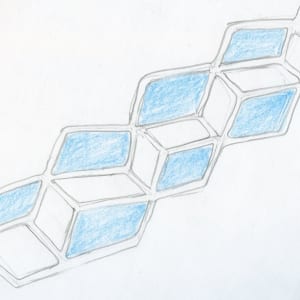

In the image I have posted at the top of the page, my initial thought was that the line-stairs that appear (by themselves, without any associated, adjacent cues) at the top of the current post would serve as a starting point, whereby a viewer would note that the line-stairs could readily be viewed as facing left or facing right.

However, field testing of the draft image has prompted the thought that such an approach appears didactic and laboured. For that reason, for future development of the image, the standalone image of the line-stairs (of which two such forms appear at the image at top of the current post) will likely not be featured.

Reading of situations, literal and metaphorical

Among other things, perception of situations in everyday life entails the flow of sensory input impinging upon the central nervous system. The mind makes sense out of such input, by ordering it in particular ways.

Everyday situations have features characteristic of ambiguous figures, where the definition – or reading – of the situation can oscillate between seeing things one way or another – such as a line-stair configuration (as in drawings at the current post) that appears to be facing left or facing right, as the case may be.

Given the above-noted scenario, what is seen in response to a given state of affairs is determined by cues prompting a given reading. Such cues may demonstrate features of rhetorical devices, which seek to organize thinking in a particular way.

It’s in the nature of the cues that what you see depends on what is in the picture, how it is arranged (the cue-configuration), and what is left out. What is left out may be by the choice of the viewer, and/or by the choice of another entity.

There’s also a third scenario where the line-stair simultaneously faces left and right. However, such a reading of a situation requires a tolerance for ambiguity, which may be rare.

The brain appears wired, in many or most cases, toward the possession of certainty, with a strong valence being attached to such a sense of certainty, as contrasted to a sense of ease in the face of uncertainty.

Art and Illusion (1969, 2000)

Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (1969, 2000) presents an overview of visual ambiguity in representational art.

A blurb for the study at the Toronto Public Library website reads:

Considered a great classic by all who seek for a meeting ground between science and the humanities, Art and Illusion examines the history and psychology of pictorial representation in light of present-day theories of visual perception information and learning. Searching for a rational explanation of the changing styles of art, Gombrich reexamines many ideas on the imitation of nature and the function of tradition. In testing his arguments he ranges over the history of art, noticing particularly the accomplishments of the ancient Greeks, and the visual discoveries of such masters as Leonardo da Vinci and Rembrandt, as well as the impressionists and the cubists. Gombrich’s triumph in Art and Illusion arises from the fact that his main concern is less with the artists than with ourselves, the beholders.

This study, which I read when it was first published, offers one perspective , among many others available, regarding the intersection of ambiguity and representation.

Symbol, symbolism, symbolist

An article (accessed Dec. 15, 2019) at the MIT Press Reader website is entitled: “A Forest of Symbols: In Conversation With Andrei Pop: The symbolists of the 19th century saw art not as a social revolution, but as a revolution in sense and how to conceptualize the world.”

An excerpt (I’ve broken the text into shorter paragraphs) reads:

Writing this book, I grew fascinated and finally impatient with all the catchy terms for what is really the same thing: sign, emblem, allegory, Leitmotiv, Ur-form, Gestalt, schema, and of course symbol and all its variations.

What is important about symbolist art — and science, which is not usually called symbolist, but should be — is that it regards symbols as purposely devised to function as such. An artificial, that is a human-made object, be it paint or sound or ink on paper, stands for some reality, abstract and conceptual like Number or Truth or concrete and dusty like a bone or a tree.

The point of the symbol is to not confuse it with the thing symbolized. Even if you take a tree to symbolize another, say a bonsai for a mighty oak, you do not conflate the two. The artwork describes reality at a distance, and it is good to know the distance. This is already a step along the road to understanding art rightly, that is self-reflectively and intelligently.

Whether it is also what the artist intended depends on the artist — was the artist careful and reflective? It is possible to notice something in an artwork that the artist totally missed. But the greatest artists invest their work richly with meaning, whether they are aware of it or not. So knowing the art helps up enormously to know the people. It is the closest we will ever get to reading the minds of those long gone.

The Longing for Less: Living with Minimalism. (2020)

The figure/ground configuration on the cover of The Longing for Less: Living with Minimalism (2020) is of interest.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

A Nov. 15, 2023 BBC article is entitled: “Magicians less prone to mental illness – study.”

An excerpt reads:

He said that what also distinguishes magicians from many other creatives is that they “not only create their own magic tricks but also perform them, while most creative groups are either creators or performers”.

“For example, poets, writers, composers and choreographers create something that will be consumed or performed by others. In contrast, actors, musicians and dancers perform and interpret the creation of others,” he said.

“Magicians, like comedians and singer-songwriters, are one of those rare groups that do both.

“Magicians scored low on impulsive nonconformity, a trait that is associated with anti-social behaviour and lower self-control.

“These traits are valuable for many creative groups such as writers, poets and comedians whose creative acts are often edgy and challenge conventional wisdom.”