Chapter 1: Dick and Jane

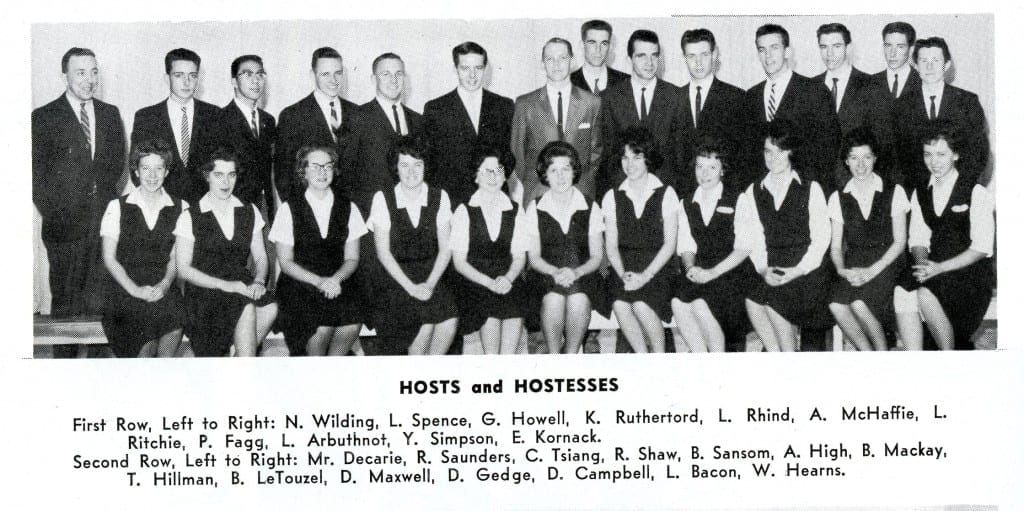

Graeme Decarie is at the far left in back row. Photo from 1961-62 Malcolm Campbell High School yearbook. Click on image to enlarge it. Click again to enlarge it further.

Graeme Decarie’s impressive and evocative MCHS Bio is outlined at a previous post:

MCHS Bio for Graeme Decarie, who taught for three years at Malcolm Campbell High School

Click here for previous posts about Graeme Decarie >

Graeme’s suggestion, that MCHS grads get to work on their stories, has prompted me to begin to work on my own story.

Each of us has the opportunity to put together our story; today is the day that I have begun writing my own autobiography story – as a subsequent post indicates.

I encourage you to start your own story today as well.

But don’t start with a scheme of any sort

The comments section (below) offers some useful pointers on how to proceed; in a comment (see below), Mr. Decarie notes:

“Start with little incidents, observations, etc. I started with the Dick and Jane reader. It turned out to be the theme of the whole autobiography.

“But start with any incident. Then, when you have enough, blend some of those incidents into the first chapter. It really isn’t hard.

“But don’t start with a scheme of any sort.”

Recent conversation with Graeme Decarie

Graeme Decarie: I’ve been writing (very slowly) an autobiography for my children. So far, it runs to some 75 pages. But I began by writing very short (1 or 2 pages) starting with ancestry, birth, earliest memories.

I thought of sending one of those short ones to Preserved Stories to encourage readers to start their own.

Jaan Pill: Yes, it would be good to post some of your autobiography stories to Preserved Stories as a way of encouraging others to write their stories.

The more stories get written, the better.

Graeme Decarie: I have, off and on, been writing an autobiography. (It’s hard to find the time when I have a long blog to pump out every day.)

It’s for my children. And I think it’s good for kids to have something like that. So – some MCHS grads might be approaching an age when they might want to think about.

I began with memories, and a bit of what I knew of family origins from the family tree. I now have 75 pages and I’m barely thirty.

Now, I’m putting these 75 pages into chapter form. It seems a workable choice that you might want to try.

So here’s a sample of the introductory chapter (a very brief one, and still in rough form.) It began by collection bits and pieces – the Dick and Jane reader from grade 1, first memories, that sort of thing.

[In the text that follows, headings have been added for ease of online reading]

Prologue

In the beginning, there was the Dick and Jane Reader, authorized by the Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal as the official text for grade one. The first page was a big picture of a neat, white bungalow with a big, green lawn. The bungalow had steps with two railings, and a clean path to the sidewalk where a boy stood, smiling. He was very clean and neat, too.

At the bottom of the page, it said: “See Dick.”

The next page had a picture of Dick running. The words at the bottom said, “See Dick run.”

Building on that theme, the next page said, “Run, Dick, Run.”

Then there was another picture, this time with a neat, clean girl in front of the neat, clean bungalow. The word at the bottom was, “Jane.”

Then the next picture showed Jane running ; and at the bottom it said—-well, you get the drift. Jane’s appearance on stage was followed by that of Spot, their neat, clean dog. He or she (the illustration was unclear on this point) was a runner, too.

It was all fiction; and doubly so for us kids in grade one of Crystal Springs School, a four-room brick schoolhouse in the Villeray District of Montreal’s North End. We knew it was fiction because none of us had ever seen a neat, white bungalow – or a lawn. Nor had we ever seen a Dick or a Jane each dressed in clean clothes that fit, and each with his or her very own room in the neat, white bungalow.

Most of us lived in tiny flats on the second storeys of masses of brick that stretched without a break on every side as far as our world reached. Each pair of these second storey flats had a balcony with a steel staircase that started out the end of the balcony, then curved out to the street.

Twelve dollars a month

The ground level flats were for people better off than us because there was only one flat downstairs for two upstairs. In our case, the landlord lived downstairs. With twelve dollars coming in from us every month, he could afford more handsome quarters than we could.

Each upstairs flat had two rooms. The front room was my bedroom. It was also my parent’s bedroom. And it was the living room for guests, who sat on the couch – which was my bed.

The back room was the kitchen with its coal stove for heat and cooking, and a small kitchen table that visitors sat around in winter. (The front room was too cold for visitors in winter, so cold that my windowsill did the duty of the fridge we didn’t have. Many of our wealthier neighbours had ice boxes which were refilled with blocks of ice delivered by horse-drawn wagons.)

The kitchen was also the radio room. That made it important because radio ruled. The whole family would sit for hours to hear Bob Hope and Bing Crosby and The Shadow. The favourite chair in the room was a stuffed one that could lean back a bit. It was also my sister’s (Winnifred’s) bed.

There was no hot water. There was a tank for it. But lighting the gas jet under the tank was out of the question because that could run up a bill of ten cents or even more. That sort of money was reserved for more tangible luxuries. You could get six chocolate marshmallow biscuits at the corner store for ten cents. (My mother, for some reason best known to herself, would always take just one bite out of the first biscuit, then gently put it back in the bag with the others. My father would happily eat all six.)

Coal stove in kitchen

The water situation eased up in winter because that was when we had the coal stove in the kitchen going. On Saturday bath night, my mother would put a tub of water on the stove. Then, all four feet ten of her would stagger with a tubful of boiling water to dump it in the tub. There, once I mixed in an equal amount of cold water, I could lie back and soak in some lukewarm water that almost went up to my ankles.

But the stove-heated water was only for the coldest of months. Most of the year, Winnifred and I would get into our bathing suits on bath night, and splash in the cold water pretending we were at the beach.

In winter, the stove was allowed to go out every day right after supper.

To the end of their days, my parents turned off the heat at night, even on the coldest nights, often opening the windows wide. When I was away at Acadia University, I went home one Christmas, and stayed with them. I woke up at two in the morning, the cold driving right through the bone.

My parents had, of course, turned off the heat after supper. Then my father, always the last one to go to bed, got the idea I must find my bedroom stuffy. (This would have been about one a.m. – when I was sleeping the sleep of the virtuous.) So he had opened my window to the 40 below zero night.

My mother, nee Jessie Miller, was a Scot born at Kilmarnock, though the family originated farther north as generations of farm servants near a highland village called Taynault. She was a twin sister to Margaret, and one of six children (including Daniel, John, Dolly and Tilda) to be crammed into the tight budget of Daniel Miller, a tailor. (Daniel’s name at his christening was Donald; but changing names was a common and casual matter in the highlands.)

Most prominent genetic traits of pit bulls

Soon after my mother was born, the family moved to London where, according to a family tale that seems to be true, her father made the coronation robe for King George V. The less often told part of the tale is that uncle Johnny stole and sold some of the gold trim.

Daniel Miller’s wife, my grandmother, was a woman whose face, body, and personality had echoes of the most prominent genetic traits of pit bulls. She had been a dressmaker and, presumably, had met Donald Miller through her work. About 1910, the family somehow scraped together the money to migrate to Canada. My grandfather went a year early, then sent for the rest.

They settled at Montreal because that was where the ship stopped. A flat, much like the one I grew up in, was found in the east end of the city. From there, Daniel Miller walked to work six days a week. On Sundays, he walked rather further to Montreal’s Chinatown, where he was a lay preacher at a mission. (At five cents each way, tram fare was out of the question.)

Then, in the great flu epidemic of 1917, Daniel Miller, the illegitimate son of a farm servant, born and raised in a highland but and ben (two-roomed cottage), died. His widow immediately took all the children out of school, and sent them to work. My mother, 12 at the time, went to a big house in the expensive enclave of Westmount. Every cent she earned for the next dozen years and more would go to her mother.

She later became a telephone receptionist, and then a stenographer. For the rest of her life, she rarely mentioned anything about her years before she met my father. And she never said a word at all about the servant years. But she never forgot them.

When my sister, Winnifred, was offered a summer job looking after a family’s child at their country cottage, my mother was humiliated and angry. “ No. That tells you what they think of us. They think we’re the class that has to go into service.”

My father was one of five boys – Irvin, Malcolm (my father), Alex, Alan, and Youbert. Their father, Alec, had a small, incinerator business based on an invention by his father. “The shop” as we called it, was a sheet metal faced building that stood at the back of a yard filled with rusting, scrap iron. My father was to live half of his life within a twenty-minute walk of the shop.

Cars

My grandfather always seemed to do well, enough so that he had a car when cars were still a luxury. My grandmother always had a full time household servant. Their home was just a short distance from ours and, though bigger than ours, was still decidedly working class. They could have afforded more. I don’t know why they didn’t.

My grandfather cared only about two people – his wife and himself. The boys were no more than cheap labour for “the shop”, and never would be more. Irvin and Alec realized that early, and struck off on their own. For the rest of their lives, they visited their parents, at most, once a year. Their children visited even less often.

Allan recognized what his father was. But he stayed with him, anyway – to look after the office, and to siphon money into his own pocket. (He was the first of the sons to have his own house and a car.)

Loyalty

My father was the only one who remained loyal to his father. I have no idea why. It cost him heavily; and he got neither reward nor thanks for it. Worse, my grandfather tried to stop my parents’ marriage – not because he gave a damn about it but because his wife loathed my mother, and would spend the rest of her life gossiping about her. She encouraged my sister and I to visit her often, probably because it was her way of slighting my mother.

My parents married at the tiny, mission church of Crystal Springs United in August of 1932 when my father, in a good week, made three to five dollars. On the night of August 26, 1933, my mother felt the coming of labour. My father walked to his parents’ house to ask for a drive to the hospital. His father refused.

My parents set out for the walk to the streetcar line on St. Denis, and then the long ride to Pine Ave, and the walk up the steep hill to Royal Victoria Hospital. There, on August 27, I was born. I was, of course, promptly diapered by a nurse. Years later, I learned that was the only diaper I ever had. When the doctor presented his bill, my father just shrugged his shoulders, and said, “I don’t have a cent.” Nor did he.

Three dollars a week

Business was slow, so my father’s salary had been cut to three dollars a week. He had been doing odd jobs of manual labour for the city, like shovelling snow to (just) get by. Meanwhile, my grandparents still drove a car, and kept a maid.

I was told that my father used to walk two miles to a charity depot every day to get free milk for me. But it wasn’t enough. I was once taken to emergency, suffering from malnutrition. But, of course, I remember none of that.

Baby sister

Of my infancy, all I remember is being held by someone outdoors, and my father coming toward us, his face and eyes lit up by a smile. In the background was a streetcar. My mother would later identify that as our Boyer Street home. I also have a vague memory of my carriage/crib, an elderly vehicle made of woven reeds. I remember peeking into it to see my baby sister when I was three.

Continuous memory began to form when I was about four, when we were living on de Gaspe. (We moved frequently, and always within the same district. I have no idea why. But I do remember, from age 6, my father and I carrying all the family possessions along the street. Luckily, there were few to carry.)

I remember, on a long walk to country cottage in Montreal North, a woman who had only two fingers on her hand giving me a banana. It was the most wonderful thing I had ever seen or tasted. To this day, a banana has special appeal for me.

Playing on the street, age of four

I remember playing on the street, unsupervised, by the age of four. It wasn’t as risky as it sounds because there were very few cars in our district. Bread and milk were still delivered in horse-drawn wagons. So was coal, and ice for the rich people who had ice-boxes. The garbage wagons were horse-drawn, great, square boxes, each on two, huge, wooden wheels. And the cry of the rag and scrap man was a daily sound as his wagon rolled down the alley.

My first friend, Stanley Short, lived just a few doors away. I once had supper at his house. We sat at a tiny, child table, and each had half a chocolate marshmallow biscuit for desert.

One summer day, Stanley and I were playing cowboys in the vacant lot across the street. As I raised my finger and shouted “tow, tow” (the French style of “pow, pow”), a pair of fingers gripped my ear, and hauled it, followed by me, across the road and up the stairs.

Calvinism

My mother, though attending the moderate, United Church, still carried in her veins the blood of the Calvinists that were her highland ancestors. Playing cowboys on Sunday was forbidden; so I was hauled, still walking backwards, all the way to the kitchen where the strap hung.

But I had an ace in the hole. I had already had enough instruction in the rules of Presbyterianism to know that God decided long in advance what we would do. It wasn’t up up to us. We were predestined to do whatever we did. And, as I remembered that, I opened the case for the defence.

“I couldn’t help it. God predestined me to play cowboys today.”

The grip on my ear relaxed a little. My mother loved a religious discussion. I felt a rush of joy as the flow of blood to my ear was somewhat restored.

“You’re right,” she said. “you’re absolutely right.”Then the flow of blood abruptly cut off as she added, “And God predestined me to strap you for it.”

Apple

By the time I was five, my sister was close to three, and she was playing on the street, too. I remember that well because my mother always warned us never to accept anything from strangers on the street. One day, when my sister was playing well down the block, a grocery boy on a bicycle offered her an apple. I grabbed her hand, and pulled her away.

A few months before my sixth birthday, we moved again, this time to a flat beside a coal yard on Berri St. This one was first floor – but only half of the first floor. It had a dank, earth-floored basement that scared me. One night, I dreamed I was going to the basement. A giant rat stood at the basement door, wearing a red uniform with brass buttons. I tried to ingratiate myself with him by telling him how nice he looked.

It was in September of that year that I started school in grade one at Crystal Springs.School. On day one, I was dressed up in my best clothes. They were not new. New clothes or new anythings were a rarity in our home. But they were washed, And they fit. Mostly.

Miss Flower

My mother walked me to the corner where we turned right, and turned again at St. Gerard to a short street called Mistral (less than a year later, we would move to St. Gerard St). Then it was a left for a couple of streets along Mistral to a wire fence surrounding a play area with a low, brick building in the centre. My mother told me to remember the way because I would be on my own from that morning on.

I lined up with the other kids at the door to the green porch that led to grade one. I took the last seat in the last row. Miss Flower, the teacher, called for me to come forward, and sit in the seat in front of her desk. As I walked forward, Stanley Short hissed, “Teacher’s pet.”

But it didn’t bother me. I didn’t know what it meant.

(Many, many years later, I would meet Miss Flower at the hand-shaking lineup after I had led the service at a church. She told me she had asked me to sit in front because I seemed such an innocent chipmunk in a rough class that she wanted to protect me.)

Carol Roberts and Esther Jones

It was in grade one that I met Carol Roberts and Esther Jones, the first loves of my life. Esther became a phys ed teacher. Carol, last I heard, became a hooker.

I also met George Root, my best friend for the next seven years or so. He became a railway policeman.

That’s also where I also met Dick and Jane. And Spot.

But they weren’t real. They were in a book. That’s why their clothes looked so new and tidy. That’s why they had that nice, little house with a lawn. It never even occurred to us to wonder whether they used newspapers instead of toilet paper, or salt instead of toothpaste. Why would it? They were just story people who never had to use a toilet or brush their teeth.

I did well in grade one, then looked forward to a great thrill. A member of our church had a shack way out in the country in St. Rose near Rivieres des Prairies (about 15 kilometres from home) where there was a free beach. We could rent a shack, improbably called Killarney Cottage, really cheap for a week with outhouse, water barrel and furniture and everything all included..

I loved it. There was a wooden dance hall built on piles right on the beach. And at night, they sometimes showed cartoon movies on a big bedsheet hanging from a line.

They looked healthy, like Jack and Jill

It was early in the week when, walking back to Killarney Cottage from the beach, I passed a wire fence that surrounded a big, neat lawn with a nice, white house. I recognized it right away. But this time it was different. There were real children playing on the lawn. I went closer, gripping the wire to stare through at the children. Their clothes were neat, so neat they looked new. And they looked healthy, just like Dick and Jane.

I don’t know how long I stared at them. They even had their very own swings and a slide. I knew I couldn’t ask to play with them. I just stared. Then, at last, I turned back to the path.

It was still a story book world. I couldn’t be a part of a storybook world. I sensed, even then and with only a slight regret, that I would never play with Dick and Jane. Not ever.

New horizons, wider possibilities

But that moment is what this autobiography is all about. My whole life would be formed by chance meetings with Dicks and Janes and Spots, each set of them more alien than the one before. At each step, I learned of new horizons to life, wider possibilities, new values, new attitudes. And, with a lot of luck, it all worked out to a fuller life than I could have imagined.

But, like that day I stood clutching the fence and looking on, I always knew I could never become one of them. Nor, as I would also learn, did I want to.

Writing an autobiography seems like such a formidable undertaking that it must be prompted by some fear of running out of time. Otherwise I’ll leave it to another day. But I really do want to write it down. For myself , for my kids. I think the process of getting this underway must be made easier. Can’t lay out a grand scheme because I know I’ll haggle with myself and get tied up in a knot. Perhaps I can approach it by writing out little incidents/observations/explanations and then stringing these snippets together at some later time. Just get started, damn it!

Yes, Charles – Just get started! With our little incidents, observations, explanations, reflections. Little things mean a lot. Graeme Decarie has assigned us a task and it’s our duty to complete it. I look forward to an update on your first draft – please know that, at all times, whatever any of us writes can be published at the Preserved Stories website. It’s great to have an audience of interested readers, who can also share feedback and reflections. Graeme Decarie’s draft of an opening chapter is such a great template. Each of us will approach the story differently; that is the beauty of such stories.

Mr. Decarie,

I very much enjoyed reading this chapter of your story. How wonderful it is that your parents took the time to talk to you about the details of their lives and the lives of their parents and grandparents. The fact that you retained these details and the details of your own young life is remarkable. You then turned these details into text that is fascinating to read. I trust your family appreciates the great gift you have given them.

Sincerely,

Sara Simmons Valentine

MCHS Class of 1968

Graeme Decarie comments:

Thanks to Charles and Sara. My parents didn’t tell me all that much – but a kid overhears a lot of comments, and comes to his own conclusions.

And for Charles, you’re quite right. Start with little incidents, observations, etc. I started with the Dick and Jane reader. It turned out to be the theme of the whole autobiography.

But start with any incident. Then, when you have enough, blend some of those incidents into the first chapter. It really isn’t hard.

But don’t start with a scheme of any sort.

Gosh. I don’t even remember the hosts and hostesses group. What were they for? That sort of group was an important feature at MCHS. I can remember current events, public speaking,film, weight lifting, dance committee…..

Those have disappeared with the spread of school bussing. And it’s a big loss.

I’ve been in touch with Gail not long ago. As I look at the picture now, I can remember quite a few of them – and I recognized Gail from her picture.

Still can’t remember hosts and hostesses, though. What did the host and hostess?

graeme