We know little about Colonel Samuel Smith; that opens many avenues for exploration

Many people in Long Branch, I’ve learned, have an interest in the history of the mouth of Etobicoke Creek.

Some time ago I selected this area of Toronto as a focus of study and began sharing what I was learning.

Jane’s Walks and Heritage Rides offer great two ways in which we can share what we’ve learned.

Such events also enable us to engage in conversation about history, which is a great way for us to learn about the past.

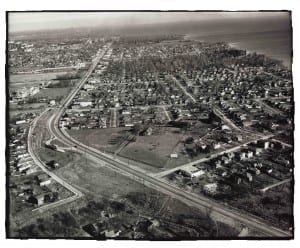

Aerial view looking east along Lake Shore Blvd West from near Long Branch Loop, Ontario Archives Acc 16215, ES1-814, Northway Gestalt Collection. Toward the back of the triangular plot of land in the middle of this November 1949 aerial photo can be seen the house of Colonel Samuel Smith, who fought on the British side in the American Revolutionary War.

I’ve also made it a project to study nearby areas including the site where Colonel Samuel Smith built his log cabin in 1797.

Here’s an overview of what I’ve learned.

The first humans to arrive in the area were Palaeo-Indian nomadic hunters who would have first seen Long Branch about 10,000 years ago at the end of the last Ice Age.

Long Branch was once located on the bottom of Glacial Lake Iroquois, and at other times has been located some ways north of Lake Ontario. The latter scenario was during the Lake Admiralty phase when the lake shrank in size.

The suitability of the soil of Long Branch for farming, once the forests had been cleared, is a result of processes that occurred during the time the land was under Lake Ontario.

The shoreline where Long Branch is now located has wandered north of its current location during the Glacial Lake Iroquois phase when Lake Ontario expanded, and south of it during the Lake Admiralty phase when the lake contracted.

Cannon at Marie Curtis Park

I’ve also learned details about the cannon near the shoreline at Marie Curtis Park.

The presence of the cannon highlights the history of technological advances in warfare.

As John K. Thornton notes in a chapter in Empires and indigenes (2011), starting around 1100, European iron workers began making stronger armour and horse breeders began breeding stronger and faster horses to carry the greater weight of armoured knights.

As John K. Thornton notes in a chapter in Empires and indigenes (2011), starting around 1100, European iron workers began making stronger armour and horse breeders began breeding stronger and faster horses to carry the greater weight of armoured knights.

At the same time, partly in response to the dominance of battlefields by armoured cavalry, European elites began to build more elaborate and stronger fortifications. As well, offensive weapons – first the crossbow and them firearms — were developed that could penetrate the stronger and thicker armour. Similarly, catapults – and eventually cannons — were developed to deal with stronger fortifications.

My parents were from Estonia. I have an interest in the history of the conquest of Estonia by Crusader knights in the 1200s.

Advances in technology of warfare played a key role in the conquest of Estonia on that occasion. As Andres Kasekamp (2010) has noted, in the Crusader attacks on the Baltic states in the early 1200s, the Crusader’s advantage over native warriors derived from the professionalism of their warrior class and their superior military technology.

The technology included the crossbow, the catapult, and the armoured knight on horseback, which Kasekamp describes as the equivalent of the tank in later warfare.

Kasekamp notes that native allies always formed the majority of manpower in the Crusaders’ force; he refers to similarities to the conquest of the Welsh by the English and the subsequent conquest of the Americas.

We know little about the personality of Colonel Samuel Smith

Little is known about the personal story of Colonel Samuel Smith, who served with the Queen’s Rangers in the American Revolutionary War; no myth has been built up around him.

To understand something about his life, it’s useful to know of the war that he fought in.

A study of the wars the colonel fought in has prompted me to study the history of warfare. What I’ve learned on that topic can be found in blog posts in the ‘Military History’ category on this website.

With regard to this topic, two major themes come to mind.

First, some of the conventions of warfare have changed.

Secondly, techological advancement is a key storyline in the world history of warfare.

Foreign relations in the American West

Wayne E. Lee’s book, Barbarians and brothers (2011), offers what a blurb for the book describes as “a sweeping examination of how intercultural interactions between Europeans and indigenous people influenced military choices and strategic action.”

This topic brings to mind Nomads, empires, states: Modes of foreign relations and political economy, Vol. 1 (2007), in which Kees van der Pijl makes a case for re-reading of world history in terms of foreign relations.

A blurb for the book outlines the author’s case:

- “Kees van der Pijl argues that by making the ‘nation-state’ the focus of international relations, the discipline has become Eurocentric and ahistorical. Theories of imperialism and historic civilizations, and their relation to world order, have been discarded. With more than half the world’s population living in cities, with unprecedented levels of migration, global politics is present on every street corner. The ‘international’ is no longer only a balance of power among states, but includes tribal relations making a comeback in various ways.”

There’s much to be said for looking at history from a wide range of perpectives. There are other perspectives, of course — other than the one that Pijl espouses — that are available for us to choose from. I would add that some of the terms that the author uses — such as the expression ‘ethnic chauvinism’ — appear at times to be better suited to polemics than to the study of history.

“In North America,” Pijl notes, at any rate, that “the frontier phenomenon of recruiting auxiliaries by the ‘imperial’ civilization primarily involved scouting by Amerindians (Lattimore 1962: 136-7).”

According to the author, native peoples adopted a pattern of dealing with foreign communities that “limited their ability to fight the United States for a sustained period. So when, in the period during and following the American Civil War, a series of brutal campaigns to subject and effectively destroy the Great Plains Amerindians was unleashed, there were initial victories but terminal defeat in the end.”

Seven Years’ War

I became interested in the world history of warfare after Steve Green, a member of the Long Branch Historical Society, made a presentation, at one of our meetings, about the history of police services in the Village of Long Branch. I began by reading about the history of police services around the world, and then began to read about the wider topic of warfare.

In my reading of military history, I’ve often come across references to the key role of the Seven Years’ War in the history of North America.

Kees van der Pijl provides an overview of this role.

By way of setting the stage for discussion, the author expresses agreement with Frederick Turner, who argued in 1893 that American history is to a large degree the history of the colonization of the American West; in particular, Pijl concurs with Turner’s claim — in Turner’s words — that “This perennial rebirth, this fluidity of American life, this expansion westward with its new opportunities, its continuous touch with the simplicity of primitive society, furnish the forces dominating American character.”

The author notes that this expansion was achieved by “displacing and effectively exterminating the indigenous peoples. Here the West was supplied with the type of personality and community and the means to conquer the planet; on the frontier, Aglietta claims (1979: 74), ‘expansion became the dominant phenomenon of American life.’ Those in the way would be dealt with harshly.”

The Seven Years’ War, as outlined in Pijl (2007), involved competition between French and English for land in connection with the fur trade in North America. The outcome of the war was the termination of French sovereignty in North America.

The archaeological remains of the Colonel Samuel Smith homestead are located on the school grounds of Parkview School at 85 Forty First St. in Long Branch. The Ontario government announced on August 25, 2011 that it would provide $5.2 million in funding to enable the French public school board Conseil scolaire Viamonde to purchase Parkview School from the Toronto District School Board (TDSB).

According to the author, the French defeat brought about the independence of the United States. Britain’s costs for the war had required taxation of the colonies — “and this was responded to in ways that the changed geopolitical configuration permitted for the first time.”

The French would , in turn, become an ally in the severance of the colonial bond, while the displacement of Amerindian tribes continued under conditions in which the American frontier continued to demonstrate an “aspect of accelerated social development.”

Frederick Turner highlights, according to Pijl, a process of a “‘return to primitive conditions on a continually advancing frontier line,’ yet with the ‘complexity of city life’ never far behind. Colonial life is a microcosm of the successive stages of social development, from hunting to trading, from pastoral herding to sedentary farming, from landed to city and factory life.”

The frontier for white Americans, Pijl adds, operated as a military training school, in which Amerindians who sought to defend themselves were labelled as aggressors: “The idea that there was an enemy to be annihilated, that no compromise was possible, thus took root in the American mindset.”

Update

A December 2015 Atlantic article is entitled: “The Accidental Patriots: Many Americans could have gone either way during the Revolution.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!