Sometimes, I could not get out any words at all; that was a long time ago

For many years, I was involved in community self-organizing on behalf of people who stutter. Years ago I formed a Toronto-based self-help group for people who stutter; our first meeting took place in September 1988 at the North York Central Library.

That meeting, for which I had made plans for several months beforehand, led in turn to my involvement in the organizing of the first national conference for people who stutter, that was ever held in Canada. The latter conference took place in August 1991; it led to the founding of an organization that is now known as the Canadian Stuttering Association. In those years, I also became active in community self-organizing at the international level.

I was involved in the early work of the International Fluency Association, which had the aim of bringing together researchers and speech pathologists from around the world whose work was focused upon the phenomenon of stuttering (and also, as it turned out, on the phenomenon known as cluttering, as the concept applies to speech) along with people who stutter.

Because I had the sense that, in practice, the IFA represented the interests of speech pathologists and researchers to a greater degree than it represented people who stutter, I was involved, in the 1990s, in the founding of another international body, the International Stuttering Association. I was also involved with the founding of the Estonian Stuttering Association.

Over many years, I moved back and forth between volunteer work in Canada and volunteer efforts at the international level. In the end, I focused in particular in helping out with work related to the Canadian Stuttering Association. During these years, I focused on two areas.

View of Lake Shore Blvd. West, looking toward the north, from inside the Long Branch Furniture store that is owned by Bill Rawson, who grew up in Long Branch before the Second World War. A recent, 2-minute Facebook video, accessible from my website, features Bill Rawson’s stories about what Elvis liked to do in his spare time. Jaan Pill photo

One area of focus has been media relations as a component of public education – as it relates to the experiences of people who stutter, and as it relates to the approaches that are available, to people who stutter and their families, when they consider how best to address stuttering.

A second area of focus has been leadership succession. I have had a strong interest, over the past 25 years, in ensuring that I am in a position to help out, in small but relevant ways, in ensuring that the Canadian Stuttering Association continues to grow and evolve as an organization, and that leadership succession along with strategic planning – which I see as a key component of leadership succession – is addressed as an ongoing process, as an integral element in the culture of the organization.

For many years, I have had no direct role in the staging of events, or in decision-making related to the Canadian Stuttering Association, or in the work of any other association, of any kind. Starting quite some years ago, I have moved on from media relations and community self-organizing on behalf of people who stutter.

View from south side of Lake Shore Blvd. West at Twenty Ninth Street. In June 2015 I was involved with a staging of a Long Branch Storytelling event at this location, in the empty lot that you can see behind the fence in the photo – part of my current volunteer work in the community where I have lived for the past 20 years. Jaan Pill photo

I have instead focused on media relations and community self-organizing as it relates to the community where I have lived with my family for the past 20 years, which happens to be Long Branch (Toronto not New Jersey). In the process, I have also developed an interest in the history of, and current developments related to, Lakeview in Mississauga, as well as Alderwood, which is just north of Long Branch, in addition to New Toronto, directly east of Long Branch, and Mimico, which is directly east of New Toronto.

Presentations to elementary school classes

The one area where I have remained active, as a volunteer as it relates to stuttering, has involved making presentations to elementary school students in the Greater Toronto Area. Once or twice a year, for the past several years, I’ve been invited by teachers, who are familiar with my previous volunteer work, to make such presentations. This generally involves quite a bit of work on the part of the teachers who invite me to speak to their classes. That is, the events need to be scheduled, a process that can involve many back and forth communications.

So, I am really pleased that I remain active, as a volunteer, in making such presentations. I never seek out such speaking opportunities. I depend entirely on teachers approaching me, and doing whatever we need to do, in order to schedule the events. I like the way that such arrangements have worked out in recent years.

I recently spoke during four periods, starting at 9:10 am, 9:50 am. 10:30 am. and 11:50 am, at Nelson Mandela Public School, a new Peel District School Board school in Brampton, Ontario north of Toronto. I spoke at the school library. The photo shows disks hat are installed in the ceiling of the library. They appear – I look forward to verifying this point – to serve an acoustical function. In my experience, the acoustical environment in the library made for a great setting for a talk. When the acoustics are just right, as was the case at this school library, everybody can hear a presenter’s every word, even without the use of a microphone and amplifier. Jaan Pill photo

I was delighted that, at a recent series of presentations at a school in Brampton, a student who as I recall is now in Grade 4 mentioned to me that he had attended the same presentation at another school a couple of years earlier. I had addressed the same topics a couple of years earlier, at another school in Brampton. The student had been in Grade 2 at the previous school, when I had spoken there, and was now (as I recall) in Grade 4, when I spoke at his new school.

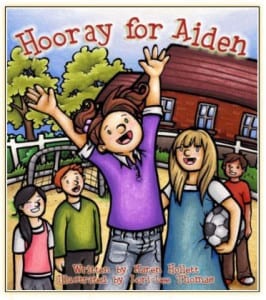

In the presentations in Brampton, I have spoken for a full day, or a half day, at a time. Two or three classes of elementary students would come to the library, and I would spend about 40 minutes each time, sharing my story and reading a story book about a child who stutters, to them. The book is called “Hooray for Aiden.”

Years ago, I was involved with offering feedback during the final stages of the production of the book. Along with other people that the author consulted at the time, I had the opportunity to offer comments as the final draft of the text for the book was in development. The book was written by Karen Hollett, who lives in Yellowknife.

Here’s a typical setting for a talk by Jaan Pill. Students sit on the floor and Jaan typically has a chair where he can sit and read. He often makes a video of his presentation, without including any recordings of the students; the camera is directed only at him. He records the sound track using a separate digital audio recorder. In time, Jaan will post a video at Vimeo.com based on his presentations at elementary schools over the years. Jaan Pill photo

Some years ago, I was invited to speak at a Kiwanis meeting in North York, regarding the topic of stuttering. For that event, I wrote and rehearsed a presentation which has also been featured at an online video at Vimeo.com under the title of Stuttering – A Listener’s Guide. The video has been seen by over 700 people at last count. It’s been well-received and I’m pleased that it’s available, for any person who wants to learn about stuttering – in particular, about what stuttering is, what is, and what it isn’t.

I developed the text for the story in such a way that I planned every word that I would say, down to the very last syllable. I like to be well-prepared when I make such a presentation. I did not read the text word for word, but proceeded instead with a set of jot notes, that reminded me of the topics that I was going to cover.

Whenever I speak to a class or classes of elementary students, I print out a copy of the text for the above-noted presentation and then write a few jot notes which serve as an outline for each presentation. I always make a point to time the talk in such a way that I have enough time to complete the reading of “Hooray for Aiden” before the allotted time, for the talk, has elapsed. I also make it a point to make the presentation an interactive one. Students have many opportunities to share information, and to make comments, pretty well all through the course of my presentations.

The following text, which is from the material that I type out, prior to a typical talk, outlines some of the key points from my talks. I trust you will find my story of interest!

I want to briefly share my own story

I began to stutter at the age of six. In my late teens and early twenties, I stuttered severely. Sometimes I could not get out any words at all. One time, I phoned someone and tried to say hello. I found the “H” sound at the beginnings of words especially hard to say. After about thirty seconds or so of trying to say hello, I just hung up the phone, without saying a word.

When I was thirty, I attended a three-week stuttering therapy program in Toronto. I attained some level of fluency as a result.

My fluency skills flew out the window; I could picture them flapping their wings

About a week after the Toronto clinic, however, I was speaking with a friend on the phone, and my newly acquired fluency skills flew out the window. I did retain enough of these skills, however, to graduate from a faculty of education. In the early years of my career, I taught small special education classes in Toronto.

Eleven years later, on May 4, 1987, I read an article in the Toronto Star describing a stuttering treatment program in Edmonton. In July of that year, I flew to Edmonton and attended a three-week treatment program at the Institute for Stuttering Treatment and Research, or ISTAR for short.

Einer Boberg and Deborah Kully of Edmonton developed this program in the mid-1980s. The program has been continuously updated ever since. In Edmonton, I relearned how to speak. I like to say I learned fluency as a second language.

The clinic taught five fluency skills

These included:

- Easy breathing

- Smooth blending of syllables

- Light touches on consonants

- Easy onset of voicing

- Prolongation of vowel sounds

I knew from experience that I would have to work hard to maintain these skills after I left the clinic. I practised these skills every day for over four years. I recorded large numbers of conversations and phone calls, and analyzed two-minute segments of them, to ensure that I was applying the skills correctly.

The self-talk insisted: “You’re not supposed to be able to do this”

Back in Toronto, I made many presentations. Every time I would be making a fluent presentation to a large audience, however, a voice inside me would say: “You’re not supposed to be able to do this. You’re supposed to be falling flat on your face.” That voice really bothered me.

At first I thought I should get some psychotherapy. But then I realized that what I needed to do was to compare notes with other people who stutter. That led me to start a local self-help group in Toronto. Our first meeting was in September 1988, at the North York Central Library.

A year later, a speech therapist who stutters, Tony Churchill of Mississauga, spoke at one of our meetings. At that meeting, I asked him about the self-talk that was bothering me each time I made a speech. Tony Churchill told me that this inner voice was telling me that I needed to adjust to some changes that had occurred in my life. After that, the inner voice never bothered me again.

Canadian Stuttering Association

My involvement with a local Toronto group led me to become active in the stuttering community. I was a co-founder of the Canadian Stuttering Association in 1991, of the Estonian Stuttering Association in 1993, and of the International Stuttering Association in 1995. In 1995, I switched from teaching special education classes in Toronto, and began teaching regular classes at a school in Mississauga.

What has worked for me will not work for all people who stutter. About 80 percent of stutterers can achieve lasting benefit from the kind of speech therapy that I encountered. Some people who stutter, about 20 percent, for reasons having to do with how their brains are wired for speech production, are not able to attain the same lasting benefit. In that case, people who stutter can benefit from a ‘stuttering modification’ approach whereby they learn to reduce the severity of their stuttering.

The Canadian Stuttering Association is a registered, incorporated, non-profit organization. We offer an impartial forum for the sharing of information about stuttering.

We do not endorse or reject any particular way of dealing with stuttering, except in cases where someone alleges that they have a sure-fire ‘cure’ for stuttering. As a rule, there is no cure for stuttering.

So that we can reach our full potential

Many stutterers can learn to control their stuttering, so it does not interfere with effective communication. If we are able to achieve control over our stuttering, it means that we are able to be more productive and reach our full potential. The earlier a person gets treatment, the better. Not getting any treatment at all is also an option.

The causes of stuttering are unknown. The evidence to date suggests that stuttering is a neurological problem affecting speech production. There is no evidence that the causes are emotional or psychological. There is no evidence that stutterers share particular personality characteristics.

Avoidance of speaking

Perhaps the most salient feature of stuttering is the avoidance of speaking situations.

When we stop speaking, we remove ourselves from the mainstream of life. Stuttering affects about one percent of the adult population – about 350,000 Canadians. About five percent of young children stutter during the years they are learning to speak. More boys are affected than girls. Most young children outgrow their stuttering – but some do not.

For an overview of statistics related to stuttering, click here >

Young children who stutter

Our advice to parents is that if your child stutters, you should seek assessment by a speech therapist who specializes in the treatment of stuttering. For preschoolers, effective programs are available, such as the Lidcombe Program.

A database of speech therapists, from across Canada, who are trained in the Lidcombe Program, is available at the website of the Montreal Fluency Centre.

How to speak with a person who stutters

What can you, as a fluent person, do when speaking with a stutterer?

- Use natural eye contact and facial gestures to show you’re listening.

- Look the person in the eye every once in a while, even when that person is struggling with words. That tells us we are still part of the human race.

- Give the person enough time to finish his or her own sentences.

- Use a relaxed pace in your own speech, but not so slow as to sound unnatural.

- Avoid remarks like “slow down” or “take a deep breath.” Such advice is not helpful.

Hooray for Aiden

Aside from movies, books offer another great way to share stories about stuttering. Karen Hollett of Yellowknife has written a children’s book, Hooray for Aiden, about a girl who stutters. The central character, Aiden, faces the challenge of speaking out in front of her class, after arriving at a new school. This book, which is driven by a powerful and compelling story, has been sold widely to school boards across North America.

Social media offers another valuable way to share information. Daniele Rossi of Toronto has a podcast show called Stuttering Is Cool. His website offers a great way for people who stutter to learn from each other. Daniele

By way of summary, the sharing of accurate information helps to counter the myths about stuttering. Children’s literature and social media can play a strong role in the sharing of our stories. The Canadian Stuttering Association offers an impartial forum for sharing of information.

If you can help us in setting up presentations to other groups, please let us know.

Thank you.

Click here for a version of this article at the CSA website >

Evidence-based practice

The Journal of Fluency Disorders, whose article abstracts are available online, is a good source, in my view, for recent overviews of research about stuttering.

As in many fields of endeavour, evidence and evidence-based practice are of strong importance, in my view, for anyone who has an interest in finding a way to deal with stuttering. In learning to deal with my own stuttering I learned, on a first-hand basis, the value of evidence when it comes to making decisions with regard to treatment options – and in a broader sense, with regard to any other decision that a person may be called upon to make.

Estonia

In 1990 I gave a series of talks in Tallinn, Estonia, that led to the founding of the Estonian Stuttering Association.

Click here to access BBC Estonia country profile >

I’ve developed another version of this story, for posting at the Canadian Stuttering website. A draft of the additional material reads as follows:

Participation

Whenever I speak to a class or classes of elementary students, I write out a few jot notes which serve as the outline for each presentation. I always make a point to time the talk in such a way that I have enough time to complete the reading of “Hooray for Aiden” before the allotted time, for the talk, has elapsed. I also make it a point to make the presentation an interactive one. Students have many opportunities to ask for additional information, and to make comments, pretty well all through the course of my presentation.

I usually begin each talk by asking the students if they know what the topic of my talk will be. Sometimes a child will say, correctly, “You’re here to tell a story.” Or sometimes they have received more specific information, from their teacher, and someone says, “You’re going to talk about stuttering.” I ask students if they know what stuttering is; various people in the audience put up their hand and they explain. Usually, a classroom of students has a pretty good sense that stuttering refers to difficulty in getting words out, as well as the repetition of words.

As my talk proceeds, I talk about the time, in my late teens or early twenties, when I tried to phone someone but had trouble with saying “hello.” After 30 seconds or so, without managing to say a word, I just hung up the phone. I ask students to imagine how that would have felt. The students invariably use words such as : “Embarrassed;” “frustrated;” “lonely;” “sad.”

Often, there is time for a Q & A, after I have read the book to the class, or sometimes we arrange a short Q & A before I read the book.

There’s always extensive discussion; the students know from the outset that I’m interested in their thoughts, and in any questions that occur to them. The talk is really more of a conversation than a lecture. Invariably, some of the students make a point of thanking me, after the talk is over, for my presentation. Often, students and I chat briefly in the hallways, if we happen to run into each other again during the course of my visit.

My sense is that the students enjoy hearing the story of a person who has achieved success in life, even thought they happened to be faced with some major challenges during the early school years – in my case, as a person who stutters. Students also enjoy learning something new – in this case, about stuttering – that they had not known before.