Graeme Decarie served as historical advisor and commentator for a 1993 NFB film about the Quiet Revolution in Quebec

A companion piece to the post you are now reading is entitled: Many changes have occurred in Cartierville where Malcolm Campbell High School was located from 1960s to late 1980s.

*

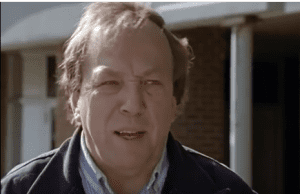

Good-looking guy on left is Graeme Decarie. Gray-haired guy on right is a blogger who ran into Mr. Decarie at a Tim Horton’s coffee shop in Moncton, N.B. on Aug. 6, 2016.

This post concerns an early 1990s documentary about the history of Montreal. A leader in the English rights movement in those years, Graeme Decarie served as a historical advisor and on-screen commentator for the film.

Previously and more recently, Graeme – who taught History at Malcolm Campbell High School in Montreal in the early 1960s – has spoken with me about the film, which is entitled:

The Rise and Fall of English Montreal (1993)

You can access the film by clicking on the You Tube link immediately above the sentence you are now reading.

In the course of preparing this post, I learned (by checking online using Google) how to take screenshots of selected areas of my screen. As a result, I’ve been able to prepare some screenshots from the 1993 documentary.

Resigns as high school teacher; pursues graduate degree

Graeme Decarie, Aug. 6, 2016. Moncton, N.B. In an email comment about the photo, Graeme writes: “It doesn’t capture the lush glory of my hair.”

As I’ve noted in previous posts, Graeme Decarie resigned in September 1963 as a History teacher at Malcolm Campbell High School (MCHS) to pursue a career as a university professor.

I didn’t know Graeme as a classroom teacher, but I got to know him because he had dealings with the MCHS student council during the 1962-63 school year when I was president of the council. I’m really pleased I got to know him then.

I’ve been in touch with him in recent years while helping to organize a Malcolm Campbell High School Sixties Reunion which took place in Toronto on Oct. 17, 2015.

Graeme Decarie, History professor at Concordia University, discusses the history of anglophones in Quebec in The Rise and Fall of the English in Montreal (1993).

In August 2016, I visited Graeme in Moncton, N.B. where he’s lived for many years:

Graeme Decarie keeps busy researching and writing his daily blog posts

After completing a Ph.D. in History at Queen’s University, Graeme Decarie taught History at the University of Prince Edward Island and later became a professor at Concordia University in Montreal. He also worked as a broadcaster with CBC and later with a CJAD Radio. Graeme resigned from high school teaching in September 1963; thus 30 years had passed, from 1963 until he appeared in the 1993 documentary.

1940s and ’50s Montreal

The Rise and Fall of English Montreal (1993) was directed and written by William Weintraub, who has written several books about Montreal including City Unique: Montreal Days and Nights in the 1940s and ’50s (1996).

Research for the film was by Terri Foxman and Graeme Decarie served as historical advisor.

The film now serves as an archival resource concerned with Montreal in the 1990s.

When watching this film, I viewed each sequence separately, as is my standard practice as a film reviewer, rather than watching the entire film from start to finish. I also made notes.

In the 1993 film, English Canadian journalist William Johnson argues that the predominant theme of French Canadian literature of the previous 150 years is anger directed at the English.

I like to have a sense how a sequence strikes me the first time I see it. The first viewing is the most important one. The second time I see a sequence, although a second or third viewing has value, it’s never as powerful or evocative as what I see the very first time.

In a message of Aug. 20, 2016 Graeme Decarie wrote:

A friend sent me a copy of this film – which I had forgotten I made. It was at the height of the Quiet Revolution in Quebec, and I was the chairman of the board for the English rights group, Alliance Quebec. It was a very tense and dangerous time.

The film was made for National Film Board. I haven’t looked at it yet but, if I recall correctly, I also did a few of the interviews in it – one in front of my elementary school – maybe one in front of my flat as a child – and maybe one in the director’s house.

[End of text]

Maria Peluso, who teaches Political Science at Concordia University, says: “The question is, ‘Why are these people wanting to leave Quebec, if they speak French perfectly?'”

Graeme has also reflected, in recent emails, about the changes that have occurred in Montreal since the 1990s. He has noted the language tensions aren’t as big a concern. He visited Montreal recently for a funeral, and stayed at a location not far from the building where our high school was located from the 1960s into the late 1980s. He spoke of a lot of changes in Cartierville, where the school was located.

Blurb for the film

A blurb for the YouTube link for the above-noted 1993 film reads:

In the past 20 years, some 300,000 English-speaking people have left Montréal, convinced they had no future in a Québec that had become increasingly French, increasingly nationalistic. In this video we meet some of the people who are moving away and recall the days, in the last century, when there were more English-speaking people than French in Montréal. The video poses a controversial question: Will the city, with its youth leaving in great numbers, become a community of the elderly, unable to renew itself?

[End of text]

Toward the end of the film Graeme Decarie notes that “Politics is about power, and power is about votes. The votes in Quebec are French. The result is that even government in Ottawa has been far, far more concerned about the French and almost indifferent to the English.”

Click here to play the video >

Role of the National Film Board in Canadian film history

The post you are now reading will provide an overview of the opening scenes of the 1993 film and some highlights based on segments that I found particularly interesting or compelling.

Related topics concern the role of the National Film Board in Canadian history, and the role of the Film Board in the history of documentary filmmaking.

A recent post addresses the historical tensions that have existed between independent Canadian filmmakers and the National Film Board; the post is entitled:

Precarious establishment: Cinema Canada article from 1978 about Canadian independent film production

Opening sequences

The opening of the 1993 documentary notes that the year 1992 was the city’s 350th birthday. [It may be noted, in turn, that in 2017 Montreal will celebrate the 375th anniversary of its founding.]

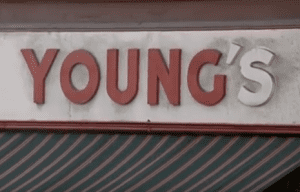

In accordance with the Quebec language legislation, a sign such as “Young’s” had to be changed to “Young” in order to change it from English to French. Similarly Simpson’s had to be changed to Simpson and Eaton’s had to be changed to Eaton.

We see people talk about how much they love Montreal and we see people moving belongings out of their house.

Language police

As the titles come on-screen, a voice over intones: “They are moving away from Montreal, away from Quebec, away from the tension between English and French.”

The voice over notes that: “It’s one of the great migrations of Canadian history.”

The French-Only sign laws is discussed, at the footage proceeds. An official of the Quebec government comments, in good English as she sits comfortably behind a desk, that from now on the signs outside of stores will be in French.

A range of scenes follow in which the effects of Bill 101, the Quebec language legislation mandating French-only signs for businesses, are documented. A voice over comments that the thought can arise that the legislation has the intent of making the English language vanish from Quebec. For Sale signs appear on the screen.

Another notable anglophone Montrealer featured in the 1993 NFB film is Carrie Derick, the first woman in Canada to be named a full university professor.

McGill University

Scenes of students at McGill University are accompanied by a voice over that notes that “many anglophone students are completely bilingual but there’s a belief that that’s not quite enough.”

A comment follows that possibly the anglophone community will in time not have any young people left, given that many are moving to Toronto or Vancouver. Scenes are also screened showing decay of buildings in Montreal’s English business areas.

A sequence shows opulent 1860s-era scenes from an era when anglophone businesses were in there ascendency; the voice over refers to rich Anglos “who lived in a house with 14 servants, most of them imported from England.” The house was situated in the legendary “Square Mile” stretching from Dorchester Blvd. to the slope of Mount Royal.

The 1993 NFB film about English Montreal notes that the Canadian Pacific Railway was an enterprise originating with anglophones in Montreal.

The voice over notes that: “By the end of the nineteenth-century, the men who lived here [in The Square Mile] controlled three-quarters of the wealth of Canada,” At this point we see historic photos of English captains of industry and socialites of the era.

There’s also a Then and Now discussion of the St. Andrew’s Ball, which since 1843 had been the “highlight of Montreal’s social season and a frolic for the rich.”

The voice over notes that in more recent years, attendees at the St. Andrew’s Ball find themselves as members of an “anxious minority, because the language they spoke was English.”

Large families living in a single room; no running water; no indoor toilets; rampant disease

The documentary notes that only a fraction of Montreal’s Anglos lived in The Square Mile. Many thousands lived well down the hill in Point St. Charles, Griffintown, and Goose Village [see second Comment, at the end of this post].

Screenshot from “The Rise and Fall of English Montreal (NFB, 1993)” showing English-speaking children in Montreal around the late 1800s.

Photos are displayed depicting poverty among Anglophone Montrealers. The voice over notes that:

“Large families slept and ate in a singe small room. There was no running water, no toilets inside. Disease was rampant, and the infant mortality was among the highest in the world. Children who lived here often worked in factories 12 hours a day. Dock workers and other labourers earned wages that were among the lowest in North America.”

Those are words that certainly paint the scene, in the event a person has the occasion (as I do, since I’ve made a transcript of much of the sound track of the film, and can read the words at my leisure) has a moment to ponder them.

Mordecai Richler comments in the film that the first two people who called for the banning of his book, Oh Canada! Oh Quebec!: Requiem for a Divided Country (1992), had not read it.

The words remind me of a summer vacation that I spent in rural, francophone Quebec with my family, when I was five years old having arrived in the spring of 1951 as an immigrant from Sweden, where my family had arrived as refugees from Estonia during the Second World War. I was born in Sweden after the war.

During that summer, I learned of the extreme poverty that some families in rural Quebec were experiencing.

Among other things, they had little food to eat. As a child, it was the first time that I had learned about the fact that some people, including families with young children, are very poor – to the extent that their health, and indeed survival, is at risk.

My knowledge of those families, in my experience as a five-year-old, was just a fleeting thing but the image of poverty has stayed with me. Reading the passage about poverty in English Montreal has brought the fleeting memory of a glimpse of the 1950s Quebec countryside back to my awareness.

Thinking about my experiences as a five-year-old has also prompted me to remember stories that my mother shared, years later, of the starvation that she and others had experienced in Estonia during the German occupation of Estonia during the Second World War.

Resentment

“Quebecois mythology,” according to the voice over, “holds that the English grew rich by exploiting the French, but those robber barons up on the hill were all equal opportunity employers, quite happy to exploit their fellow anglos as well as the French.”

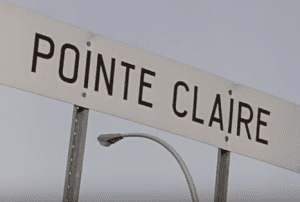

The fim describes how in Pointe Claire on the Island of Montreal, in accordance with the Quebec law regarding signage across the province, a hyphen had to be added between the words appearing on signs in all public places, as Point-Claire (with the hyphen) is the French version of the spelling and Point Claire (no hyphen) is the English version.

The first commentary by Graeme Decarie follows.

“We were English,” he notes, “but we didn’t entirely think of ourselves as English and French. That really wasn’t the way it was divided.”

Graeme refers as well to “a really deep resentment of the English, because the way Quebec has traditionally operated, the rich English and the rich French ran it between themselves, and the rest of us were expected to follow behind.”

A sequence of shots and a narrative follows that emphasizes that some homeless and poor people in Montreal are Anglos. A voice over notes that “for most Anglos, those bygone days were not all that good.”

The foregoing overview of the opening scenes from the film provides a sense of how the film begins. I will highlight two sequences that I found of particular interest.

Roman Catholic Church

The first sequence is concerned with one of several commentaries by Graeme Decarie about Montreal history. In a sequence leading up to one of his comments, the film outlines successful efforts, starting in the early 1960s with anglophones leading the way, to preserve the Papineau House and other historic buildings in Old Montreal.

“With anglophones leading the way,” the narration notes, “Old Montreal with its rich French heritage came to be preserved.”

The film next turns to the role of the Roman Catholic Church in the history of Quebec. For more than three centuries, the narration notes, the church dominated the life of the province.

“To it,” a voice over asserts, “goes much of the credit for preserving the French language in this corner of North America. But there was a price to pay. The church urged its followers to stay on the farm, to look inward, to avoid contact with the English. Thus, by largely withdrawing from the field, they left the way clear for the anglos to dominate industry and commerce.”

The 1993 NFB documentary notes that for more than three centuries until the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, the Roman Catholic Church dominated the life of Quebec. “To it,” a voice over adds, “goes much of the credit for preserving the French language in this corner of North America. But there was a price to pay. The church urged its followers to stay on the farm, to look inward, to avoid contact with the English. Thus, by largely withdrawing from the field, the left the way clear for the Anglos to dominate industry and commerce.”

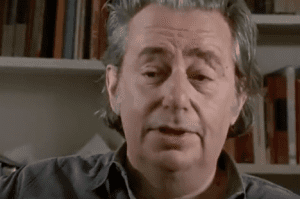

After this setting of the scene, Graeme Decarie appears (starting at 27:00 minutes into the film) in two interview sequences. In the second sequence (starting at 27:32) he speaks in a close-up.

The transition from medium shot to close-up works well. The close-up underlines the point that Graeme is making.

The film almost never uses to identify people who appear on the screen. However, in this case there is a two-line caption reading: “Graeme Decarie, Historian.”

“Education in Quebec,” Graeme notes (at 27:00) in a medium shot, “was based on the values of seventeenth-century Catholic France. Those who were born to lead, the children of the rich, got excellent education in private schools.

“Those who were born to follow – the children of the poor – well, there was no point in wasting education on them. The result was that in Quebec, [for] the rich, the only interest in public schooling was to keep the cost down.

Graeme Decarie notes, in a close-up sequence at 27:32 into the film, that “The French often blame the English for the educational problems of their society, but the fact is that it was their own elite that did them in.”

“Even after the Quiet Revolution, when the education system was democratized, the private school remained very important for the children of the rich.”

Close-up sequence at 27:32 minutes in the film

The screen switches to a close-up of Graeme who remarks:

“The French often blame the English for the educational problems of their society, buy the fact is that it was their own elite that did them in.”

Effort to save an English school at 41:34 minutes

An Anglophone parent speaks out – eloquently and cogently – against a plan to move English-speaking children out of a school, and to bus them to another school.

There is also a scene toward the end of the film where a woman – who was a key spokesperson for an effort to save the English section of a public school – speaks eloquently about the injustice of a forced move of English children from the school that they have shared, without problems, for many years with French students.

There’s a level of coordination, between her words, her body language, and her tone of voice that strongly holds a person’s attention.

It’s clear at once why she ended up as a leader in the efforts to keep the English students at the school that they had much enjoyed attending.

That is a part of the film, starting at 41:34 minutes, that can readily stand on its own, separate from whatever scenes appear before or after it.

Oscar Peterson is among the entertainers featured in a segment, about “the nightlife of bygone Montreal, in the 1993 NFB documentary.

I very much like this sequence, which begins with a shot of children chanting “Save our school.”

“Save our school”

St. Kevin’s School is the name of the school and the plan is for the children to be bussed away to another school. “They won’t permit us to share the school with the French children,” a leader of the anglophone school community says, “because they feel our language, English, is a detriment; they feel that we will contaminate the French children.”

The voice over notes: “Sept. 8, 1973. The Van Horne Building, one of the great mansions, is bring torn down to make way for a nondescript office building.”

The speaker notes that the French parents at the school had been surveyed. They had no objection to sharing the building. She said if the matter were taken out of the hands of politicians it would better.

“The common people,” she says, “have absolutely no objection to sharing buildings, French and English together.”

She is a highly articulate speaker.

Resources related to Quebec history

I arrived in Montreal as an immigrant in 1951 at the age of 5. I left to go to university, returned for a short time, and then settled in Toronto starting in 1975. I like the idea of learning a bit more about the history of the city.

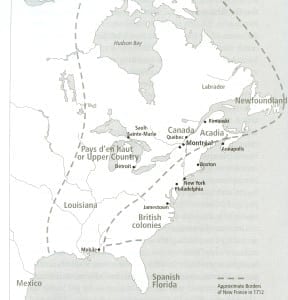

The History of Montréal: The Story of a Great North America City (2007) features a map (p. 41) of the French Empire in North America as it appeared in 1712. The next year, 1713, marked the first step, through the Treaty of Utrecht, the caption on p. 42 notes, in the dismantling of the empire. Click on the image to enlarge it; click again to enlarge it further.

The interviews featuring Graeme Decarie have given me a sense, more than any email conversation can do, of the role that he played as a leader in the English rights movement in Montreal.

As a result of viewing the film, I’ve made a list of online references, primarily from the Toronto Public Library – about the history of Quebec and about documentary making – that I would not otherwise have had the motivation to find out about.

Among the books I’ve begun to read, from the public library, is Language, Citizenship and Identity in Quebec (2009).

Among things, the book notes that anglophones and francophones have made some measure of progress in getting along. The book refers, as well, to the time when English Montrealers played an elite role in society.

I’ve also been reading The History of Montréal: The Story of a Great North America City (2007), which has enabled me to learn of the distinction between Saint-Laurent (the suburb) and Saint-Laurent (the ward), as noted at another post.

As well, I’ve had a look at Opening the Gates of Eighteenth-Century Montreal (1992). The book is concerned with architectural history with a focus on fortifications and other military installations associated with North American military history. The capitulation of Montreal in 1760 after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759 is highlighted, as is the expansion of Montreal beyond the original fortification walls the surrounded it at an early stage of its history.

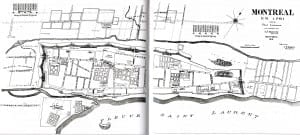

The History of Montreal: The Story of a Great North American City (2007) includes (p. 65) a redrawn version of an older map depicting Montreal as it appeared in 1761, a year after the Capitulation of Montreal. The Capitulation in 1760 occurred subsequent to the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759. The map shows Foubourg (that is, the suburb of) Saint-Laurent north of the fortified walls of the town. The map also shows suburbs to the east and west and the camps of the British occupying forces. The original older map is featured in Opening the Gates of Eighteenth-Century Montreal (1992). Click on the image to enlarge it; click again to enlarge it further.

The book notes that people who could not afford to build houses within the fortified boundaries began to build them along roads heading west, north, and east of the walls. The suburb that developed along the road leading north was called St. Laurent.

Also of interest for me, given that I’ve begun to read overviews of the documentary format by Bill Nichols, is a Sept. 17, 2015 No Film School article entitled: “Nichols’ 6 Modes of Documentary Might Expand Your Storytelling Strategies.”

Previous posts about documentary filmmaking

Previous posts, which among other things talk about the history of the National Film Board, include:

Precarious establishment: Cinema Canada article from 1978 about Canadian independent film production

Erving Goffman began his graduate work in Chicago in 1945

More details about St-Laurent

From the Montreal Memories Facebook Page, I’ve found this great link, from http://www2.ville.montreal.qc.ca :

Click here to access a Canadian Encyclopedia reference to Norgate Shopping Centre >

American Documentary Film (2011)

Also of interest: American Documentary Film: Projecting the Nation (2011). A blurb notes:

“This book examines how documentary films have contributed to the American public sphere – creating a kind of public space, serving as sites for community-building, public expression, and social innovation. Geiger focuses on how documentaries have been significant in forming ideas of the nation, both as an imagined space and a real place. [Publisher’s description].”

Information about sugar that was kept from us in the 1960s

I like to read stories that tell us things we did not know, at the time, about what was going on in the 1960s.

By way of a recent example, a Sept. 13, 2016 CBC article is entitled: “Sugar industry paid scientists for favourable research, documents reveal: Harvard study in 1960s cast doubt on sugar’s role in heart disease, pointing finger at fat.”

Click here for previous posts about sugar >

All Governments Lie (2016)

Click here to access a Trailer for All Governments Lie (2016) (opening at TIFF) >

With regard to the topic of documentaries, a Sept. 8, 2016 CBC The Current article is entitled: “All Governments Lie documentary takes aim at mainstream media.”

The opening paragraphs read:

“All governments lie” was the mantra of investigative journalist I.F. Stone. It’s also the title of a new documentary film premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival.

From the ’50s to the ’70s, Stone worked to reveal government and corporate deception in his weekly newsletter.

[End of text]

The subtitle for the film is: Truth, Deception, and the spirit of I.F. Stone.

Federal sponsorship scandal following the 1995 Quebec Referendum

The Rise and Fall of English Montreal (1993) focuses on Montreal history up until about 1992. Recent news reports highlight the 1995 Quebec Referendum and the federal sponsorship scandal the followed in the aftermath of the referendum.

An excellent overview about this period in history is provided in a Sept. 14, 2016 CBC The Current podcast.

The online CBC article introducing the podcast is entitled: Liberal sponsorship scandal trial recalls perception of party entitlement.

Opening the Gates of Eighteenth-Century Montréal (1992)

Among the resources I have begun to read, since viewing the 1993 film, is Opening the Gates of Eighteenth-Century Montréal (1992).

I much enjoy this study, published by the Canadian Centre for Architecture and distributed by MIT Press. A blurb reads:

Based on a fifteen-year study of manuscript sources from Europe and North America, Opening the Gates of Eighteenth-Century Montréal focuses on the interrelationships of three key elements of Montréal’s urban form: its fortifications; the ownership, distribution, and use of property within its walls; and the nature of its buildings.The first section of the book, Fortifications, traces Montréal’s development as one of the most important military and commercial centers of the French colonial network arching from Louisbourg to the Great Lakes and down the Lake Champlain and Ohio corridors. It also discusses the related development of the town’s fortifications. Town, the second section, examines how Montréal’s diversifying economic activities – many connected with the building, maintenance, and supply of inland military posts – influenced land use and building within the walls. The last section, Buildings, focuses on the urban house, Montréal’s principal building type in the eighteenth-century, examining it in its material and social environments: morphology of town and fortifications, distribution of institutional buildings, and formative legal traditions – metropolitan French above all, but later also British and American. The demolition of the walls (1801-1817) that had defined the town blurred town and suburb and augured a new urban form.

Peopling the North American City: Montreal 1840-1900 (2011)

Another book about Montreal history is entitled: Peopling the North American City: Montreal 1840-1900 (2011). I enjoy this book because among other things it talks about the lives of everyday people.

Generalizations related to economic, political, and social trends are of interest, and have their place – as do descriptions of everyday life – and death, and overviews of the individual choices that people make in the course of their day-to-day lives.

Chapter 4, “The Hazards of City Living,” is particularly instructive, and evocative.

By way of example, research based on archival records indicates that the age of weaning had a significant impact on infant mortality rates in nineteenth-century Montreal.

That is, cultural differences related to breast-feeding practices gave rise to differential rates of infant mortality in the three major communities (French Canadian, Irish Catholic, and Protestant) that comprised the majority of the population.

The study notes (p. 106) that “Public health agents today argue that child-saving interventions require alteration of a sociocultural system.”

The chapter prompts me to think about the ongoing relevance of health epidemiology even now, with regard for example to what research continues to discover concerning the deleterious effects of sugar over-consumption.

Culmination of twenty-five years of work

A blurb for the book reads:

Benefiting from Montreal’s remarkable archival records, Sherry Olson and Patricia Thornton use an ingenious sampling of twelve surnames to track the comings and goings, births, deaths, and marriages of the city’s inhabitants. The book demonstrates the importance of individual decisions by outlining the circumstances in which people decided where to move, when to marry, and what work to do. Integrating social and spatial analysis, the authors provide insights into the relationships among the city’s three cultural communities, show how inequalities of voice, purchasing power, and access to real property were maintained, and provide first-hand evidence of the impact of city living and poverty on families, health, and futures. The findings challenge presumptions about the cultural “assimilation” of migrants as well as our understanding of urban life in nineteenth-century North America. The culmination of twenty-five years of work, Peopling the North American City is an illuminating look at the humanity of cities and the elements that determine whether their citizens will thrive or merely survive.

[End of text]

The book notes (p. 362) that “Before Expo ’67, Mayor Jean Drapeau ordered the removal of 350 families and demolition of the centuries-old [Goose Village] neighbourhood, whose nickname recalled the geese of the march.”

Given my strong interest in the lives of everyday people as a subject of historical inquiry, I am highly impressed with this detailed, evidence-based resource. It’s a great piece of work!

Fascism and the Italians of Montreal: An Oral History: 1922-1945 (1998)

I’ve also been reading Fascism and the Italians of Montreal: An Oral History: 1922-1945 (1998). Among the people interviewed is Hugh MacLennan who had the opportunity to acquaint himself with fascism and antifascism while travelling in Italy in the 1930s during his student days at Oxford, where he had arrived from Nova Scotia as a Rhodes Scholar.

The oral histories include a comment by MacLennan who observes (p. 55) that “Canada was built by losers.” He lists among the losers “the French, who explored most of the continent,” the United Empire Loyalists, “who didn’t go along with the American Revolution,” the Highland Scots, “who were kicked out by their own clan chiefs,” and the Irish, “victims of the potato famine.”

The comment prompts me to think of key points in history when Canada was a winner. By way of example, the War of 1812 is, as I understand, seen by the United States as a victory because the U.S. was able to hold its own in a war with the major power of the time, namely Great Britain. On the other hand, from the Canadian perspective, the war was a victory for Canada given that the U.S. did not succeed in its project to conquer and annex Upper and Lower Canada during the war:

John Boyd committed his infantry before his artillery could properly support them: Battle of Crysler’s Farm, Nov. 11, 1813

Battle of Chateauguay (1813) was one of two great battles that saved Canada

The author of Fascism and the Italians of Montreal: An Oral History: 1922-1945 (1998) notes that archival resources, regarding the relation between fascism and Italian Canadians during the period under study, are scarce. Oral history serves as a great way, I would say, for readers to learn what individuals recollect about times gone by, and the mindset they bring to perceptions about the past.

My sense is that reference to archival sources – such as are available, or that become available with the passage of time – is also essential, nonetheless, if a person wants to get a sense of what was actually going on, with regard to fascism in Quebec and elsewhere in Canada during the 1930s and 1940s.

Archival resources that come to mind, with regard to the period under review, include among others:

Young Trudeau, 1919-1944: Son of Quebec, Father of Canada (2006)

Young Trudeau, 1919-1944: Son of Quebec, Father of Canada (2006) is the first book in a two-volume series; the second volume is entitled: Trudeau Transformed, 1944-1965: The Shaping of a Statesman (2011).

The blurb for the first volume reads:

This book shines a light of devastating clarity on French-Canadian society in the 1930s and 1940s, when young elites were raised to be pro-fascist, and democratic and liberal were terms of criticism. The model leaders to be admired were good Catholic dictators like Mussolini, Salazar in Portugal, Franco in Spain, and especially Pétain, collaborator with the Nazis in Vichy France. There were even demonstrations against Jews who were demonstrating against what the Nazis were doing in Germany.

Trudeau, far from being the rebel that other biographers have claimed, embraced this ideology. At his elite school, Brébeuf, he was a model student, the editor of the school magazine, and admired by the staff and his fellow students. But the fascist ideas and the people he admired – even when the war was going on, as late as 1944 – included extremists so terrible that at the war’s end they were shot. And then there’s his manifesto and his plan to stage a revolution against les Anglais.

This is astonishing material – and it’s all demonstrably true – based on personal papers of Trudeau that the authors were allowed to access after his death. What they have found has astounded and distressed them, but they both agree that the truth must be published.

Translated from the forthcoming French edition by William Johnson, this explosive book is sure to hit the headlines.

None is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933-1948 (1982)

None is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933-1948 (1982)

A blurb for the book is not available at the Toronto Public Library; however a blurb for the following book (below) refers to the 1982 study.

Nazi Germany, Canadian Responses: Confronting Antisemitism in the Shadow of War (2012)

Nazi Germany, Canadian Responses: Confronting Antisemitism in the Shadow of War (2012)

A blurb reads:

It has been thirty years since the publication of Irving Abella and Harold Troper’s seminal work None is Too Many, which documented the official barriers that kept Jewish immigrants and refugees out of Canada in the shadow of the Second World War. The book won critical acclaim, but a haunting question remained: Why did Canada act as it did in the 1930s and 1940s? Answering this question requires a deeper understanding of the attitudes, ideas, and information that circulated in Canadian society during this period. How much did Canadians know at the time about the horrors unfolding against the Jews of Europe? Where did their information come from? And how did they respond, on both public and institutional levels, to the events that marked Hitler’s march to power: the 1935 Nuremberg Race Laws, the 1936 Olympics, Kristallnacht, and the crisis of the MS St Louis?

The contributors to this collection – scholars of international repute – turn to the wider public sphere for answers: to the media, the world of literature, the university campus, the realm of international sport, and networks of community activism. Their findings reveal that the persecutions and atrocities taking place in Nazi Germany inspired a range of responses from ordinary Canadians, from indifference to outrage to quiet acquiescence. It is challenging to recreate the mindset of more than seventy years ago. Yet this collection takes up that challenge, digging deeper into archives, records, and testimonies that can offer fresh interpretations of this dark period. The answer to the question “why?” begins here.

Contributors include: Doris Bergen, Chancellor Rose and Ray Wolfe Chair in Holocaust Studies, University of Toronto, Richard Menkis, Department of History, University of British Columbia; Harold Troper, Department of Theory and Policy Studies in Education, OISE/University of Toronto; Amanda Grzyb, Faculty of Information and Media Studies, University of Western Ontario; Rebecca Margolis, Centre for Canadian Jewish Studies, University of Ottawa; Michael Brown, Department of Languages, Literatures and Lingustics, York University; Norman Ravvin, Institute for Canadian Jewish Studies, Concordia University; and James Walker, Department of History, University of Waterloo.

The reference to Papineau House, in the 1993 film, has prompted me to attend more closely, than would otherwise be the case, to the story of Louis-Joseph Papineau. Every writer that I’ve encountered, who sums up Papineau’s role in some way, has a characteristic approach to the framing of the story.

One version is provided in The History of Montréal: The Story of a Great North America City (2007). The text (p.73) is by Paul André Linteau translated by Peter McCambridge:

The English-speaking population was no longer limited a handful of merchants and administrators: they were present in every class of society, swelling the ranks of artisans, as well as labourers and servants, among whom most were Irish. Moreover, the city’s new ethnic makeup followed its streets and lanes: the English and Scots dominated the west, the Irish the southwest, and the French-speaking Canadiens the east. Needless to say, there was also some overlap between these divisions, with some French Canadians in the west and some English in the east.

The arrival of the British, quickly and en masse, also had a significant impact on Montreal’s culture. The English lan guage was everywhere. Protestant churches, schools, and associations multiplied. The city’s architecture was trans formed as it began to draw on British inspiration.

This turnaround led to political and ethnic tensions that climaxed in the 1830s when the Parti patriote, formerly the Parti canadien led by Louis-Joseph Papineau, headed a political struggle that culminated in the rebellions of 1837 and 1838. Essentially, the political goals of the Patriotes, like those of the Reformers in Upper Canada led by William Lyon Mackenzie, involved obtaining self-government for the colonies. Violence grew and the city streets became a battle ground for loyalists pitted against Patriotes. However, the rebellions did not break out in Montreal itself – there were too many British about and the garrison was too strong – but in the surrounding area where Canadiens dominated. The rebellions were crushed by the military, consecrating the political victory of English-speaking Montrealers. Montreal now belonged to them.

[End of excerpt]

This is extremely interesting and has put a little more meat on the bones regarding the period of time when my G G Grandfather, in the Coldstream Guards, was sent from England to the British Garrison in Montreal, where he served between 1838 and 1842.

Although I have been responding to you in a different thread, I have predictably drifted into other areas on this marvellous website. My husband (we are both ex RAF officers) is passionate about all military history and I am forwarding this website to him.

Whilst his depth of knowledge and particular passions are the Cold War and the American Civil War (we have just finished 4 enjoyable years doing ACW re-enacting here in England, and were actually at Gettysburg on the day of 9-11 when visiting battle sites during an interval in yet another holiday in New England), his pre-existing interest in North American history has grown toward Canada with the discovery of my family connections.

We visited Fort Ticonderoga many years ago, on Lake Champlain, but at the time I did not realise I had so many past – and present – family connections not far north of there, in Montreal.

Yet again, you have provided a plethora of links to interesting tangents in the history of ‘matters Canadian’ which are a part of my ancestral life. I look forward to ‘wasting’ (not!) more time un-peeling the onion layers of Canadian history in this marvellous website.

Thank you, Jaan.

Jo Morris-Turner

Good to read your message, Jo.

I was most interested to learn of your biographical background, and the biographical background as well of your husband. I am delighted that you find my site of interest!

A Canadian military veteran who has had a strong and beneficial influence on my website in years past (and who has a strong influence even now) is the late Phil Gray. If you click on the link in the previous sentence, you will come across many posts associated with a message that he originally sent my by email.

As well, I’ve written extensively about the wartime work of William Stephenson and related topics such as the Special Operations Executive and irregular warfare.

I began to write about these topics, in recent years, because I had been thinking, since the 1970s, of comments by a woman, whom I have met on a number of occasions over the years, who had worked with William Stephenson during the Second World War.

Also among my recent interests is exploration of the value of historical details related to formative experiences as they relate to history (including recent history) in particular under – but not limited to – conditions, which can be frequently encountered, where accurate biographical details about a person may be in short supply.

Bedst,

Jaan