At a post regarding Cartierville and Ville St.-Laurent history, I have added comments about the history of Ville St-Laurent

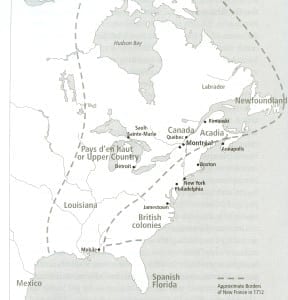

The History of Montréal: The Story of a Great North America City (2007) features a map (p. 41) of the French Empire in North America as it appeared in 1712. The next year, 1713, marked the first step, through the Treaty of Utrecht, the caption on p. 42 notes, in the dismantling of the empire. Click on the image to enlarge it; click again to enlarge it further.

Updates

A May 2017 CBC interactive webpage is entitled: “Montreal is 375 years old, but how old are its buildings?”

A May 17, 2017 Montreal Gazette article is entitled: “Montreal’s history did not start 375 years ago.”

[End]

A previous post is entitled:

Q & A with Graeme Decarie regarding the history of Cartierville and Ville St. Laurent

At a comment at the latter post, I have added some details, which were new for me, concerning the history of St. Laurent (or Saint-Laurent, as it is also spelled, in some sources). By way of bringing attention to the details, I am featuring them at the post you are now reading.

I am really pleased to have the opportunity, 53 years after I finished Grade 11 at Malcolm Campbell High School. to be learning these new things, that I had not known about before, about the history of Ville St. Laurent (also spelled as Saint-Laurent).

My knowledge remains indistinct and hazy; any assistance that you as a site visitor can provide by way of adding accurate details to my understanding of the history of Cartierville and Saint-laurent will be much appreciated.

A book called Opening the Gates of Eighteenth-Century Montréal (1992) describes how, when Montreal grew beyond its original boundaries (the boundaries being a walled fortification), one of the suburbs that developed on a road leading north of the walls was the Saint-Laurent suburb.

Saint-Laurent the suburb c.f. Saint-Laurent the ward

A passage (pp. 97-77) in The History of Montréal: The Story of a Great North America City (2007) has enabled me to learn of the distinction between Saint-Laurent (the suburb) and Saint-Laurent (the ward). The passage reads:

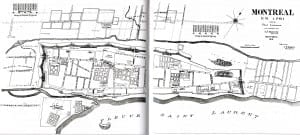

The History of Montreal: The Story of a Great North American City (2007) includes (p. 65) a redrawn version of an older map depicting Montreal as it appeared in 1761, a year after the Capitulation of Montreal. The Capitulation in 1760 occurred subsequent to the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759. The map shows Foubourg (that is, the suburb of) Saint-Laurent north of the fortified walls of the town. The map also shows suburbs to the east and west and the camps of the British occupying forces. The original older map is featured in Opening the Gates of Eighteenth-Century Montreal (1992). Click on the image to enlarge it; click again to enlarge it further.

In 1792, the government redefined the boundaries of Montreal, setting them at a distance from the walls of 100 chains, based on the old British measurement, or approximately two kilometres. The new territory, an enormous rectangle, contained the old town, the suburbs, and a sizable rural area around them.This ensured Montreal had plenty of room to grow for decades to come.

The trend continued: the suburbs especially grew and in 1825 contained a little over three quarters of the population. The biggest were the suburbs of Saint-Laurent, Quebec, and Saint-Joseph. In 1831, the government divided the area into wards for the first time, and then redivided it in 1840 and, in particular, in 1845. As of 1845, Montreal had nine wards:three in the old town (West, Centre, and East) and six elsewhere (Sainte-Anne, Saint-Antoine, Saint-Laurent, Saint-Louis, Saint-Jacques, and Sainte-Marie). The town would remain divided in this way, with only minor modifications, until the end of the century.

[End of excerpt]

The above-noted book – which includes a map, based on a historical map (where the details are harder to make out), showing among other things the early St. Laurent (or Saint-Laurent, or in English: St. Lawrence) suburb north of the original fortified walls – is written in the style of a breezy travelogue through time – fun to read, but if you seek a more nuanced account, there are other sources that also warrant a close read.

Lives of Montrealers in the nineteenth century

A related Comment, at a post entitled Graeme Decarie served as historical advisor and commentator for a 1993 NFB film about the Quiet Revolution in Quebec, has also been a source of much interest to me, as it provides a sense of what life was like in Montreal – including in the suburbs – in the nineteenth century.

The text of the latter Comment has already been featured in a separate post, and I am pleased to include it in this post as well. The text reads:

Peopling the North American City: Montreal 1840-1900 (2011)

Another book about Montreal history is entitled: Peopling the North American City: Montreal 1840-1900 (2011). I enjoy this book because among other things it talks about the lives of everyday people.

Generalizations related to economic, political, and social trends are of interest, and have their place – as do descriptions of everyday life – and death, and overviews of the individual choices that people make in the course of their day-to-day lives.

Chapter 4, “The Hazards of City Living,” is particularly instructive, and evocative.

By way of example, research based on archival records indicates that the age of weaning had a significant impact on infant mortality rates in nineteenth-century Montreal.

That is, cultural differences related to breast-feeding practices gave rise to differential rates of infant mortality in the three major communities (French Canadian, Irish Catholic, and Protestant) that comprised the majority of the population.

The study notes (p. 106) that “Public health agents today argue that child-saving interventions require alteration of a sociocultural system.”

The chapter prompts me to think about the ongoing relevance of health epidemiology even now, with regard for example to what research continues to discover concerning the deleterious effects of sugar over-consumption.

Culmination of twenty-five years of work

A blurb for the book reads:

Benefiting from Montreal’s remarkable archival records, Sherry Olson and Patricia Thornton use an ingenious sampling of twelve surnames to track the comings and goings, births, deaths, and marriages of the city’s inhabitants. The book demonstrates the importance of individual decisions by outlining the circumstances in which people decided where to move, when to marry, and what work to do. Integrating social and spatial analysis, the authors provide insights into the relationships among the city’s three cultural communities, show how inequalities of voice, purchasing power, and access to real property were maintained, and provide first-hand evidence of the impact of city living and poverty on families, health, and futures. The findings challenge presumptions about the cultural “assimilation” of migrants as well as our understanding of urban life in nineteenth-century North America. The culmination of twenty-five years of work, Peopling the North American City is an illuminating look at the humanity of cities and the elements that determine whether their citizens will thrive or merely survive.

[End of text]

The book notes (p. 362) that “Before Expo ’67, Mayor Jean Drapeau ordered the removal of 350 families and demolition of the centuries-old [Goose Village] neighbourhood, whose nickname recalled the geese of the march.”

Given my strong interest in the lives of everyday people as a subject of historical inquiry, I am highly impressed with this detailed, evidence-based resource. It’s a great piece of work!

Nineteenth century climate

When I read about the nineteenth century and earlier centuries, I think about the changes in carbon emissions that were set into place starting around the early 1600s and that began to manifest themselves in centuries that followed.

Regarding these trends, a Sept. 18, 2016 Five Thirty Eight article is entitled: “Why We Don’t Know If It Will Be Sunny Next Month But We Know It’ll Be Hot All Year.”

More details about St-Laurent

From the Montreal Memories Facebook Page, I’ve found this great link, from http://www2.ville.montreal.qc.ca :

Click here to access a Canadian Encyclopedia reference to Norgate Shopping Centre >

Archival photo of Cartierville

I recently came across a Jan. 31, 2021 Facebook post from Peter Halliday that I want to share; Peter writes:

I posted this shot a few years ago, but because of the renewed interest in the Canadair shot below, I thought I’d re-post this one too. Some landmarks are visible already – the path of highway 15, the railroad tracks, Sacre Coeur hospital, the neighbourhood where MCHS would be built, in the lower center of the photo. I think the picture was from the 1950’s, but I am not sure when… If you want the full zoomable photo/file you can try this link:

*

The History of Montréal: The Story of a Great North America City (2007) is a good read. I’ve learned a lot about Montreal, at least at a surface level, or at least one version of it, that I didn’t know about, from reading the book.

That said, the book would benefit from some copy editing, in my view. There was one chapter where I kept on encountering, time after time, the phrases “needless to say,” and “not to mention.” Don’t need such repetition.