Where will the people go: Toronto’s Emergency Housing Program and the Limits of Canadian Social Housing Policy, 1944-1957

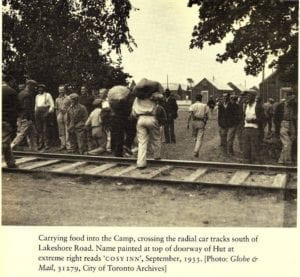

Click on the image to enlarge it; click again to enlarge it further. We owe thanks to Mississauga Ward 1 Councillor Jim Tovey for sharing this archival photo with us. “This is an image,” Councillor Tovey notes, “of the Federal Men’s Work Camp instituted in 1933, during the Depression. These are the buildings that became the social housing after WW II.”

A subsequent post is entitled:

Toronto’s 1950s emergency housing: An informative, comprehensive overview by Kevin Brushett (2007)

A previous post is entitled:

Seeking information: Wartime and postwar housing at Small Arms Ltd. in Lakeview and elsewhere

I have recently learned of a March 1, 2007 paper, in the Journal of Urban History, entitled “Where will the people go: Toronto’s Emergency Housing Program and the Limits of Canadian Social Housing Policy, 1944-1957,” by Kevin Brushett of the Royal Military College of Canada.

Click here to access a PDF file of the article >

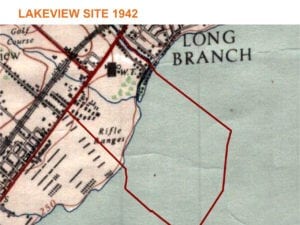

The map (click on the image to enlarge it) is from Jim Tovey, in response to a question from Garry Burke (see comments, at the end of this post). Councillor Tovey writes: “My understanding is the social housing was located in the barracks previously occupied by the Lorne Scots after WWII. Here is a map showing showing the barracks. The cluster just south of Lakeshore (in red) and in between the other red line and the creek. I believe the Work Camp was closer to Cawthra Rd. You should check with Mathew Wilkinson at Heritage Mississauga.”

The article, as the abstract notes, challenges the assumptions that Toronto’s homeless were “shiftless welfare bums”

The abstract reads:

“In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Canadian cities dealt with a growing housing shortage while the federal and provincial governments argued over who would implement the provisions of the 1944 National Housing Act. This was particularly true in Toronto. As Torontonians celebrated the construction of Regent Park, Canada’s ‘Premier Slum Clearance and Public Housing Project,’ nearly 1,350 Toronto families were housed in dilapidated old army barracks and staff houses. Until Regent Park, the shelters were Toronto’s only rent-geared-to-income housing project. This article challenges the assumptions that Toronto’s homeless were ‘shiftless welfare bums’ and examines the strategies shelter residents used to survive the often brutal conditions in which they lived and how they hoped to escape them. Finally, it argues that the inability of municipalities to replace emergency shelters with decent affordable housing reveals the long-standing reluctance of Canadian governments to develop social-housing programs to eliminate homelessness.”

Background related to my interest in this topic

Click here to access previous posts about Regent Park >

I have received messages from Douglas Hanlon on January 2017, through my Preserved Stories website, and am pleased to have the opportunity to follow up on his messages.

Mr. Hanlon has a close, personal connection to wartime and postwar housing in Canada. He would like me to post information at my website about the housing that was in place, in those years. He would like this information to be more widely known, including among the grandchildren of former residents of wartime-era housing in Canada. I would like to follow through on his request.

I have contacted a number of people and am starting to organize the material related to Canada’s wartime housing.

Any information and links that you, as a site visitor, would be able to share would be much appreciated.

Updates: Comment from Graeme Decarie

Click here for previous posts by and about Graeme Decarie >

Graeme, a retired Concordia University history professor, has commented:

I can’t even pretend to know much about those houses – but I do know a little bit about the reason for them.

These went up, usually in blocks, at the end of the war. All were one and a half stories. All had asbestos shingles. I remember my father taking us to see one when he got back from the navy. But, at $3,000, it was hopelessly out of our reach.

The reason for them was more subtle.

MacKenzie King was no socialist or people’s politician. He was a cold and calculating man. But he profoundly wanted to stay in power. He came to power in the late 1930s, and he embarked on welfare projects begun by R.B. Bennett, a coldly wealthy man who was quite reformed as he came to realize the suffering of the Depression. So King had to stay on that path. As well, he had to allow government to take full control over the economy. (This was not King’s style. He was the pet poodle of the business elite. But without government control, the economy would have gone haywire, and the country might well have collapsed.)

In the course of the war, he was under tremendous pressure to maintain morale by telling people what it was they were fighting for (besides adoration of the king).

One of the morale boosters he hit on was relatively cheap housing for returning soldiers. He did it – strictly because he had to do something…..

graeme

[End]

Also of interest:

“Wartime Housing Limited, 1941 – 1947: Canadian Housing Policy at the Crossroads,” Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine, vol. 15, n° 1, 1986, p. 40-59.

Houses for Canadians: A Study of Housing Problems in the Toronto Area, 1948, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1948

An excerpt from the 1948 paper reads:

“Obviously the most convenient and economical way of providing the community with an adequate supply of decent accommodation is through the economic market for new housing. If those who can afford to own or to rent new housing could maintain such a volume of production that every family could be well-housed and obsolete housing could be successively removed, then in the process of time there would be no housing problem. All the resources of science and industry must be applied to the removal of the obstructions at the point where, in a free economy, the bulk of the housing supply should be concentrated – at the mid-point in the income scale. Unless a balance in the ratio between incomes and housing costs can be established, the shortage will continue to stack up against families in the lower-income ranges. Unhappily, any study of the economic factors involved seems to lead inevitably to the conclusion that a balance of incomes and housing costs is most unlikely to be established at a level which would produce an adequate supply of housing. This has certainly been the experience of all other industrialized nations and there are no factors peculiar to our economy which indicate that Canada is likely to be an exception to this experience. In fact, the requirements of shelter in our stern climate are likely to make the economics of housing in Canada especially intractable.”

[End]

A Dec. 12, 2007 Spacing article is entitled: “Wartime Housing.”

Housing challenges call for ingenuity, which takes many forms. A Jan. 23, 2017 Toronto Star article is entitled: “Thank you for being a friend . . . I can buy a house with: Meet a new generation of golden girls: Shared home ownership of a renovated heritage house in Port Perry gives aging owners a comfortable – and affordable – place to grow old.”

So many articles and papers are available regarding the topic of housing. Here are a few of them.

A Jan. 12, 2017 Canadian Press article in the Toronto Star is entitled: “Federal government looks at creating new housing benefit for low-income renters: Generally, housing benefits are provided to renters who need help paying the bills, but if a renter moves to a new unit, the supplement doesn’t follow.”

A Jan. 20, 2017 Toronto Star article is entitled: “Big city mayors to demand cash for social housing: Canada’s big city mayors to meet in Ottawa Friday where they’re expected to push for urgent funding to repair social housing.”

Studies available at the Toronto Public Library include:

Social Policy and Practice in Canada: A History (2006)

The Emergence of Social Security in Canada (1997)

Military Workfare: The Soldier and Social Citizenship in Canada (2008)

The latter book, which I read with interest some years ago, is no longer available for loan at the Toronto Public Library; it is now Reference only. I have discussed the study in a November 2011 post entitled:

The American Revolution, the First Nations, and Colonel Samuel Smith

Hi Jaan,

The 1933 photo of the Federal Men’s Work Camp is most interesting. But those huts are not the ones families moved into after the war. The huts I vividly remember had been had been built specifically for the army. Do you know where the Men’s Work Camp was located? Might those shanties have been levelled for army barracks at he outbreak of the war?

Our Hut 7 bordered a large parade square, and was near the water tower that stood long after the Army Camp was demolished. At the south end of the square was a large boiler building that chugged out the hot water that heated all the huts, and provided hot water for showers and laundry.

Three years ago I jumped through hoops trying to get into records of the Camp and Staff House gathering dust in the provincial archives. Most of the records are still “restricted,” most annoying. I wondered who the lucky person was who perused the material I wanted and thought, “Gosh. This is too personal, too risqué.” What was given me was…not worth reading.

I look back at Camp and Staff House life and shake my head. It was barely better than an existence. But my parents always told us, when we grumbled about having so little, that they had lived under much tougher conditions in Northern Ontario during Dirty Thirties. As kids, we always found things to do. The buildings were literally overrun with children. My sister and I both paraphrase that great line from Charles Dickens’ “Tale of Two Cities:” “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

Wonderful to read your message, Garry.

I have sent out some messages to several people, including to Mississauga Ward 1 Councillor Jim Tovey, to see if they can help us find answers to the questions, regarding the 1933 photo, that you have raised.

Some of the best material, for historians, is made available when archives are finally opened, after being hidden from view for decades. Let us hope that a time will come when the provincial archives, dealing with the records of the Camp and Staff House, are opened.

I look forward to sharing much more information, such as concerning details of your own childhood experiences at the Camp and Staff House, at the Preserved Stories website. I’m really pleased that Douglas Hanlon, who has moved from one place to another a total of 150 times in his life, contacted me with the hope that I would gather together information about Toronto-area emergency housing in the 1940s and 1950s. I have taken on the task and am delighted that there are many people out there, such as yourself and also Cairine Johnson, who have some great stories to share!

I will be organizing material, from the emails that you and also Cairine have sent me recently, and will post the material at this website. At the same time, I’m also working on studying available resources, at the Toronto Public Library and online, that describe the overall housing situation, as well as the emergency housing situation, in the Greater Toronto Area in the 1940s and 1950s. Plus there are other history-related (and storytelling-related) projects that I am working on, and that also tie in with the topic at hand.

I have cleared my desk, made myself comfortable, and am working on this project with much interest and enthusiasm.

Thanks, Jaan. There is an excellent published article on Emergency Housing sites following the war, GECO, Stanley Barracks, Little Norway, etc. It was that article that sent me running to the archives, which turned out like trying to get into personal letters of the medieval popes. I’ll have to unearth it from my very disorganized filing system. I believe it was published in sociology journal.

Thee was a very nasty piece in a Mississauga publication seven or eight years ago. The writer , who knew nothing about the Camp and Staff House, labelled them “black eyes” in Lakeview, inhabited by lazy welfare recipients. He did admit a few of the folks may have been truly down on their luck.

One had to take extreme caution, he wrote, whenever entering the grounds of those rundown buildings. I took the man to task, and he admitted that what he had written was based on hearsay. He must have interviewed one, maybe two, very uninformed residents. But I’m sure that for many folks of Lakeview and Port Credit, those building were indeed an eyesore, just like many public housing buildings today in the GTA. But the Camp and Staff house were very safe; no gangs, guns or drugs then. And no racial issues.

Who knows, people may have used the term “white trash” for tenants in those buildings. You couldn’t really blame them after seeing, every Saturday morning, the beer delivery truck parked, and the driver lugging in cases. My parents always ordered two, sometimes three. I always grit my teeth when I recall when they switched to powdered milk, not bottled, to “save money.” Powdered milks in the early ’50s was like coloured water. But they did same money; we hardly touched it. More cash for those Saturday morning beer deliveries?

One blessing for our family was the monthly baby bonus allowance. Always on time, and we really depended on that cheque for the week’s groceries.

Please let me know, Garry, what the name of the sociology article is, that you read some time ago, if you are able to locate it. I would like to read it, for sure. The Kevin Brushett (2007) article is one that I’ve posted a link for, and am currently writing a post summarizing its contents.

Over the years, I’ve encountered anecdotal remarks about the Emergency Housing at Small Arms Ltd., during conversations in the course of events at or near the Small Arms Building in recent years. I’ve also read at least one published account, again based on anecdotal remarks, in a Mississauga business newspaper.

I could sense at once that such anecdotal accounts are based on hearsay, and serve to mindlessly repeat stereotypical views in the absence of first-hand evidence. In contrast, the experiences that you have shared, and other people who have actually lived in the postwar buildings have shared, offer a more accurate, balanced, and nuanced view of things.

I look forward to learning, and sharing, more information with a focus on accurate and balanced reporting. I am delighted to know of your own experiences – such as about the beer, the powdered milk, the monthly baby bonus allowance, the appearance of the buildings, and other details – and look forward to learning much more, and sharing (through posts at this website) what I learn.

Among the small details that I’ve learned, and that I look forward to learning more about, is that kids (probably living, I imagine, in nearby postwar housing) used to play hide-and-seek around the wooden baffles located at the Long Branch Rifle Ranges between the Small Arms Building and the Lake Ontario shoreline.

A topic that comes to mind, as I think about these things, is research by Amy Cuddy among others regarding how stereotyping works and what drives bias, stereotyping, and prejudice in our society.

It’s a topic that I’ve explored at a number of posts during the past year.

Mississauga Ward 1 Councillor Jim Tovey has mentioned, in response to Garry Burke’s question:

“My understanding is the social housing was located in the barracks previously occupied by the Lorne Scots after WWII. Here is a map showing showing the barracks. The cluster just south of Lakeshore (in red) and in between the other red line and the creek.

I believe the Work Camp was closer to Cawthra Rd. You should check with Mathew Wilkinson at Heritage Mississauga.”

Click on the image to enlarge it; click again to enlarge it further

I lived in the army camp, and the staff house had very fond memories of being a kid there playing in the bunkers and the rifle ranges. Many happy memories. We didn’t know we were so poor.

Your comments are of much interest. A number of people have mentioned growing up in this general area including in Long Branch; a number of people have mentioned how the concept of being in a state of poverty did not register during their childhood years.

I am reminded that there are many other valid ways to measure the quality of life besides the economic aspect. Important as the economic aspect is, it is not the only variable that is in play, when we consider what makes for the good life. Young children especially tend in my experience to have a very good grasp of what makes for pure enjoyment in our days.

Following message is from Ted Long sent to his son Pat Long:

Hey Son…The last e-mail you sent me has the story from Garry Burke regarding the army camp and staff house…He’s right, those pics dont show the real army camp we lived in…He mentioned Hut 7, we lived in hut 13 and across the only street heading west inside the camp had huts 1, 2, 3 around the outside ring road of the camp..outside of that, on the west was the rifle range where we all played on the mounds and in the target bunkers down by the lake…He’s also right about the boiler room that supplied water to all the huts..on the right side of our hut was the fire hall or shed and behind it was the big barn where mr. noble ( one arm only ) the rag or sheeny man collected and bagged in sacks, newspapers and rags and junk…

After Hurricane Hazel hit in 1954 most people were moved to other places, we went right across from small arms into the staff house which was on the west north corner of dixie road and lakeshore and then like most people from those two areas all ended up in various war time houses across the city, we first went to 54 Norway Avenue in the beaches area ( between kenilworth avenue and elmer avenue and kingston road and queen street ) after that we or most people from the army camp and staff house ended up in regent park north…there was no regent park south yet….we lived on the third floor of the first 3 story building west of river street on dundas street….

Point being if Garry Burke was there, I should know him and would like to hear more and see more pics, meantime i think uncle steve has a picture of mom and us four from the camp, moms holding steve cause he was just a baby, so that would be around 1950 or 51…Forward this info to your man and ya, for sure i would be interested in digging further…Dad

Hi Jaan,

Re kids playing hide-and-seek around the wooden baffles between Small Arms and the Lake, that never happened. That area was well fenced for test firing Bern guns during the early 1950s. Climbing that fence, or squeezing under, would have be suicidal during that period.

We did play on the large earthen embankments behind the targets on the rifle range, but never during the summer when army units were using them. One memory I have is being in awe watching tracer rounds being used at night. I had never seen that. I’ve often wondered what the target was. Was some soldier half a mile away in a safe enclosure holding up a light on a pole? Maybe they were told just to fire rounds to see what using tracers were like.

About roaming those fields, there was safety in numbers. You seldom saw a child there alone. I was always with two or three chums, and felt more at ease if one was a year or two older than me. If we spotted other kids, our first thought was, “friend or foe.” If we knew them, and liked them, we waved and joined forces. Those “hunting parties” were usually all male. Occasionally, a girl would be with them, but it had to be a gal considered a “tomboy,” one who handle herself. The character Scout in “To Kill a Mockingbird” reminded me of that type. There were a couple of girls our age in the Camp who were very tough. We respected them, and were careful never to challenge. I learned at an early age those were the very kids to become fiends with, veritable bodyguards.

Talking games, in the Staff House during winter months and after supper, boys would play tag throughout the hallways of the building. Great fun, but it must have be agony for residents hearing hordes of kids racing down the hall, and leaping from landing to landing down the stairwells. There was a myriad of routes you could take in that building, and never go outside. That is a very fond memory. Being a fast runner had its dividends for any boy in the Army Camp and Staff House; there was sometimes safety in speed. Now, I suspect, kids that age are mesmerized sitting quietly in front of a computer after supper.

Hi Garry,

Good to read your message. I recall how active I was as a child, playing all kinds of games and roaming across my own neighbourhood in Cartierville in Montreal (including on wooded areas) in the mid and late 1950s. I remember at Kindergarten in the early 1950s at Van Horne School in the Snowden district on Montreal, I just loved running all around the recess yard, in all kinds of chasing games, in a crowded recess yard. At recess times in the baby boom years, I guess that recess grounds everywhere in Canada were absolutely swarming with kids having fun. That was so much fun. How much I loved to run! I still make it a point to be physically active.

When I taught Grade 4, I remember students would tell me that among the favourite highlights of Grade 4 was having friends to hang out with and playing with friends at recess.

I will be interested to learn more, from additional sources, regarding the question of whether or not kids played hide-and-seek at the baffles.

The reason I’ve referred to such pursuits is the following paragraph in an online September 2013 City of Mississauga Cultural Heritage Assessment entitled: “Long Branch Outdoor Rifle Range.” The document refers to a single rifle range; the usage I’ve adopted for my website is to speak of it as “ranges.” Anyway, the paragraph in question reads:

Immediately after the end of the War in 1945, the City of Toronto leased all the land as part of the emergency housing program for Toronto area families. The Outdoor Firing Range was no longer being used as a firing range and children would climb the baffles and backstop and use them to play hide-and-seek. However, due to urban and industrial development, shooting resumed on site but only at the Indoor Firing Range in 1968 when the South Peel Rod and Gun Club signed a lease to use the building. Today, the Outdoor Firing Range is a public park with walkways going past several of the wooden baffles. The land is now owned by the Region of Peel.

End

Your first-hand observations are of much value, as they indicate that in the 1950s, some firing was still going on at the rifle ranges.

I will be most interested in exploring this topic further. I like to take very much an evidence-based approach toward such details, as is standard and necessary in any kind of responsible journalism and reporting. In this case, I will be interested to find out, when time permits, what the source is for the above-noted mention of the playing of hide-and-seek. I also look forward to learning of any corroboration of statements, from as many sources as possible, regarding this interesting question.

Hi Jaan,

I just keyboarded a long message and it went…somewhere. Poof! Dang. That never happened when I used to use pen and paper.

Rifle range or rifle ranges? Semantics. We’re talking where the Lakeshore Generating Station stood, all 52 hectares, construction stated in June of ’58 and the facilities closed in 2005(?). Those wooden and sand baffles, still standing behind the lone Small Arms building, were no part of the rifle range(s), and were used exclusively for test firing weapons, particularly Bren guns. They just wanted to make sure they worked. During my years at the Staff House, we frequently heard them doing that. That might have been where the kids played hide-and-seek, but it would have been long after the Small Arms was shut down, and the high fence around those baffles removed. There is still a concrete wall just south of those baffles on the edge of the lake from that era, sadly marred with graffiti. If bullets missed the baffles, they would hit that wall, and you can still see it was hit many times.

There were large earthen mounds, with very large numbered signs, at the south end of the rifle range, on the very edge of the lake. The signs marked the target area for shooters. For example if someone, hundreds of yards away, was assigned to target #1, he could easily locate that point, and then wait until the red target was raised. Directly in front(north) of those earthen mounds were sunken concrete accommodations where soldiers hoisting and lowering the targets kept score. When that was going on, kids kept well away from the rifle range(s). Serious business. During the autumn and spring, we used to play in those bunkers, and sometimes used the two-seater privies.

When I did research on Ontario’s school cadets, I found frequent references in the press of Toronto’s militia units going to the “Long Branch Rifle Range” for practice. That would have been the decade before WW 1. The Boers taught the Brits, and us, the importance of marksmanship with a rifle. There was a shooting range for militia units near Niagara-on-the- Lake, but that was little use for the well-heeled Toronto militiamen. It was a time when Canadians looked down on professional soldiers. A standing army was considered just too expensive, a waste of tax money. The belief was that a citizen army, well trained with the rifle, and having imbibed a smattering of military discipline at two-week summer camps, would be able to repel any invaders. In those times, “invaders” meant Americans. The “militia myth” from the War of 1812 was still very much in vogue. World War 1 would change all that.

Hi Garry,

It’s really valuable for me to know the additional details, about how things worked at the rifle ranges. Your overview gives me a much better picture of things, than I had before.

The War of 1812 is a topic that is of interest to me. In particular, I’ve enjoyed learning details about the Battle of Crysler’s Field and related events of that war:

John Boyd committed his infantry before his artillery could properly support them: Battle of Crysler’s Farm, Nov. 11, 1813

Battle of Chateauguay (1813) was one of two great battles that saved Canada

When Britain Burned the White House: The 1814 Invasion of Washington (2013)

Hi Jaan,

Nice to know you’re a War of 1812 aficionado. I have always been disappointed visiting the Lundy’s Lane site. The surroundings are so…sleezy. There at a couple of markers indicating positions of regiments during that battle, and few graves of the combatants, but that’s it. The four or five times I’ve ben there, usually in the evening, the little church/museum was closed. I wrote/complained to Parks Canada, and they were most understanding, hopeful that more funding would enable that tiny site to be take on the appearance of an historic parcel of land. If that battleground had been in the U.S., you can bet no money would have been spared to preserve it in detail. Perhaps the tourist attractions like the Falls, and the casino, Lundy’s Lane just doesn’t draw that many. The times of been there, I’ve been the only person wandering the grounds.

Hi Garry,

Your comments bring to mind, for me, that each of us deals with history in our own, characteristic way.

I’ve visited a few historic sites in Canada, and have noted that usually there’s not a huge crowd of people joining me on such occasions. Typically, I have the site all to myself. In my case, the lack of interest warrants celebration. As a general rule, people in Canada don’t make a practice of putting people from the past on pedestals. As a rule, Canadians don’t get much excited about history. By way of example, little information is available, in the archival records, concerning the first European settler in Long Branch, Col. Samuel Smith. I like that. I live in Long Branch and initially I knew nothing about local history, and would not have cared less.

The absence of a record about Col. Samuel Smith has meant that, in my case, I began to read about world military history, and about the history of the British empire and the times in which the colonel lived and engaged in warfare on the British side. I first became interested in his story when I learned that, in 1797, he had built a log cabin, at a location within a one-minute walk from where I have lived in Long Branch for the past 20 years. I began such a study project simply as a way to get a sense of what the colonel’s life was about, given that few details, related to his personal life, are available in the historical record.

A few years later now, I’ve learned so many things, and have had the opportunity to share some of what I’ve learned in a variety of venues, including at this website. The more I’ve read, and studied, the more my views about the past have changed – have been modified, and refined. I’ve had the freedom, the opportunity, to do that, because there are not a lot of myths built around such a figure, as the colonel, in Canada. Elsewhere, all manner of myths would have been built around him; it wouldn’t have been as easy for a person to just start reading, and just embark upon a personal project to learn more, and figure out what’s what.

In relation to history, I speak of myths as a way to refer to coherent, cohesive, fake-news stories about the past. The manufacture of such myths, and related traditions, for specified political, social, and purposes related to power relations, is a central feature of nationalisms, ideologies, and strongly held belief systems, in all of their many forms, in many countries around the world.

Canada has its share of myths, of course, but Canadians do not generally make it a practice, so far as I can see, to build their lives, institutions, and life projects around fake-news stories of this nature. The one exception concerns myths as they relate to the country’s current and past relationships with its First Nations citizens. In that area, myths are entrenched, but we appear to be making a measure of progress in dismantling them.

Little, or relatively little, is known in Canada about the decisive battles during the War of 1812 that had the result that the United States dropped its plan to conquer and annex Upper and Lower Canada. Thus when I went to visit the site of the Battle of Crysler’s Farm, I noted that, on that day in the summer a few years ago, that very few people were there, visiting the site. Few people know about the battle. I very much like that. I like the fact that it’s a characteristic of Canada that we do not as a rule use history to promote nationalism.

I had the same experience visiting a War of 1812 exhibit at Fort York in Toronto, some years ago. Almost no one else was there, as I went about checking out a first-rate exhibit. Did it bother me? Not in the least. So long as a few people were there (and it might just have been a slow day), they got a tremendous opportunity to learn something about the past. That’s what matters, in my view. It takes just a few people, a few dedicated individuals, to get all manner of things done in this world.

I am also pleased that in recent decades, an interest has developed in knowing about, and understanding and appreciating, the First Nations contribution to the building of Canada – as, by way of example, the critical role played by First Nations warriors fighting on the British side in the War of 1812. Carl Benn among other historians have made it a point to delve in depth into this aspect of Canadian history. Among my own current projects is a plan to learn much more about the First Nations aspects of local history, in Long Branch and Lakeview. There’s so much to learn, for those of us – whatever our numbers may be – who have an interest in looking back, and connecting what we learn to what we see before us in the here and now.

Some further thoughts:

We can say myth is what is required to make functional a situation or circumstance that is otherwise hard to deal with, that is otherwise more dysfunctional than it is when people are guided by myths. It’s an attempt to gloss over some inconvenient details of life through an attempt at sense-making through mythology.

There are lots of myths associated with Canada but they are not particularly overblown or overwhelming. There is an understanding that the study of history in Canada is open in a healthy way to contention, as each generation creates its own version of history anew. It’s a process in which professional historians and everyday citizens can participate.

I’ve given the matter still further thought. I was reminded of a post from some time back:

What can we learn about evidence-based practice when we read about Tecumseh?

As well, I think about two posts that deal with a variety of myths (and demystifications) related to the history of Montreal:

Peopling the North American City: Montreal 1840-1900 (2011)

Graeme Decarie served as historical advisor and commentator for a 1993 NFB film about the Quiet Revolution in Quebec

So I have to revise my generalization, expressed in a previous comment, suggesting that Canadians are less prone to myths about the past than Americans. Canadians are subject to myths as well, although perhaps one can say that on some occasions, the myths in Canada do not take hold quite as strongly as in the United States, where it appears the myths about that country – such as the myth of American exceptionalism, which reminds me of myths related to the British empire and other empires in history – are really drilled into people every day, from the time they are very young.

I’m reminded, as I think about these things, about a Jan. 4, 2017 Guardian article, entitled: “The Canada experiment: is this the world’s first ‘postnational’ country?: When Justin Trudeau said ‘there is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada’, he was articulating a uniquely Canadian philosophy that some find bewildering, even reckless – but could represent a radical new model of nationhood.”

For relaxation I sometimes read accounts of the War of 1812. By way of example, I’m currently reading a message of Oct. 26, 1813 from Robert Purdy to James Wilkinson, describing the American defeat at the Battle of Chateauguay, one of the two battles that saved Canada in those years. The source is The War of 1812 (2013), published by the Library of America. Wilkinson led the army that was defeated at the Battle of Crysler’s Farm, the other battle that saved Canada.

The larger context also comes to mind. In this regard, a Feb. 14, 2017 London School of Economics and Political Science article is entitled: “Mastering Trump’s mastermind: Sebastian Gorka and the struggle between Islam and the West.”