Hansard excerpt (7): Presentation by Jennifer Keesmaat at Oct. 17, 2017 OMB Reform hearing

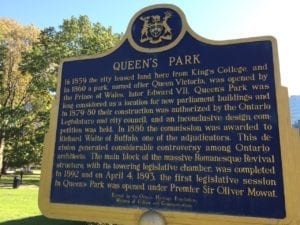

This post features an excerpt from the Hansard transcript of the Oct. 17, 2017 OMB Reform hearing at Queen’s Park.

My notes of the above-noted hearing are featured at a previous post entitled:

In the text below, I begin with my own notes, after which I conclude with the Hansard transcript, of the presentation by Jennifer Keesmaat.

Please note: I have posted the text in adherence to the Copyright provisions regarding Hansard texts.

A previous post features the following overview of the Jennifer Keesmaat presentation

At 5:00 p.m., Jennifer Keesmaat, former Chief Planner, City of Toronto, spoke.

Speaks of a lot of ground having been covered. Says new legislation will function within a pro-growth context. The challenge is the infrastructure to keep up with growth – such as parks and schools, that is, the things a complete community needs.

Planning is good – it directs growth to existing growth areas.

We need density. We need density to support transit, to reduce the environmental footprint. We need [that which is] proactive.

We do not need an approach, of a building at a time. We need a planning framework. “It’s difficult to say how transformative that [aspect of the new legislation] is.”

Currently, one individual fights [the citizen’s] interests. [Nor clear if I have this correct, from my notes. Please refer to the Hansard transcript, when it is posted.]

Describes OMB as a problem way [of making decisions], based on a very narrow framework.

Refers to Places to Grow; refers to density targets.

If we had a policy-drive process, then …

In this case, it is NOT a quasi-judicial process.

Unelected officials are making decisions. “How much does respect for democracy matter?”

The changes proposed in this Bill represents a fundamental shift. Planning Departments will re-shift efforts toward proactive planning.

We are a pro-growth Region. Vast majority [of planning proposals] do not go to the OMB. They are aligned with Provincial Policy and are accepted by local communities.

Certain developers work in collaboration with stakeholders. Refers to Westbank Corp. development for Bloor and Danforth – for former Honest Ed’s site. Refers to over 20 heritage buildings that have been included in the development.

This does not get done when it gets punted to the OMB.

Bill 139 is reinforcing how we use policy to get democracy to work.

Refers to situation wherein officials don’t take responsibility for decisions because it will be shunted to the OMB.

Refers to Eglinton Crosstown. Development industry said: Put as-of-right zoning in place. “We did. You can put up an eight-storey building.”

Development industry said: We want to see new development along transit corridors. Developers came back for more [after original proposals accepted]: The OMB has enabled this [that is, has enabled the coming back for additional density].

Notes that the question is: Should policy based on sound planning guide what we do?

Refers to mitigation of shadow impact.

Adds that the OMB does not respect local Council. Not the way to go.

Q: Refers to what is consistent with the developer side, and with the Municipal side: That is, it’s broken. If we work together, make the right decisions: How do you envision [the previous tensions, that are inherent in the process] would remain?

A: Two answers.

1) Proposed change to OMB brings us in alignment with a typical Plan Process.

2) Negotiation should not be site by site, but by the Area Plan level.

Q: Refers to major development: We need to know up front. Most appeals involve developer wanting more density. How to deal with that?

A: In Toronto we have 19 Corridors pre-zoned for mid-rise development.

Q: You’re enthusiastic about the Bill?

A: The Bill will change how Municipalities plan. More Area Plans, more Neighbourhood Plans.

Q: Refers to a situation where Policy drives decision making, and where local elected officials take more responsibility.

A: Absolutely. It’s also the better part of democracy. Accountability must be taken. The way Bill 139 it’s structured, [there’s a requirement] to look at policy. That compares to a dangerous way – that is, decisions made behind closed doors at the OMB, with no accountability. Notes that OMB Adjudicator may be a person who lives in Kingston, who makes a Planning decision affecting a Toronto Neighbourhood.

Q: What is the greatest impact, of Bill 139?

A: An opportunity for re-engagement by communities in the Planning process.

Q: Some sectors, we won’t see any more development. We won’t see density [that is required] to support transit and other things.

A: Refers to the Provincial Policy Framework. The Policy promotes growth. Otherwise, a proposal is overthrown at the OMB.

Refers to a situation: A developer says, “I bid eight storeys; I want to build what Policy allows.” Speculator, however, outbids the latter developer.

Says believes Bill 139 will reward the latter kind of developer, who wants to build the mid-rise buildings that the Policy allows.

Below is the Hansard transcript of the same presentation

The Acting Chair (Ms. Cindy Forster): We will now move on to Jennifer Keesmaat.

Good afternoon. You will have up to 10 minutes for your presentation. If you could state your name for the record, please.

Ms. Jennifer Keesmaat: Fabulous. Thank you very much. My name is Jennifer Keesmaat, and I am the former chief planner and executive director of the city planning department in the city of Toronto.

I have practised planning for over 20 years in the province of Ontario and have attended many OMB hearings and mediations. I have overseen, over the course of the past five years, over 5,000 development applications in the city of Toronto alone, and have led a team that has been fully engaged in the consultation process on behalf of the province for reform of the OMB system.

I want to begin by saying that it’s important to recognize the proposed changes to how the OMB will function in the context of a pro-growth context.

Since 2009, approximately 140,000 housing units have been completed within the city of Toronto. This is an astronomical amount of new housing growth, by any measure, to the extent that the greatest challenge we face is the infrastructure to keep up with the new housing units that have been built, including water capacity, parks, schools, neighbourhood facilities, and all of the components that are essential to creating a sustainable, thriving, complete community over the long term.

1700

By any measure, we are a beacon in the world with respect to our planning process, and we recognize that a key part of our success is the provincial planning framework within which we operate, including Places to Grow and the Greenbelt Act, which have fundamentally transformed land use planning in the region, directing our growth to existing built-up areas in such a way that we are beginning—beginning—to transform our region to become transit-oriented and a fundamentally more sustainable place.

In the absence of these policy frameworks, the dream of being a transit-oriented region will not materialize. We need density. We need to be transforming and adding growth to existing built-up areas that currently do not have the growth to support high-frequency transit. We know that this is not only critical to our quality of life in reducing congestion times but it is also critical to reducing our environmental footprint and becoming a more sustainable region.

It’s important to note that our planning needs to be proactive. We need to be thinking about the future that we want to create, and creating policy frameworks that will result in that future. That is our objective: to not create a city or a region one building at a time, but to have a clearly articulated planning framework that will result in the future that we have, in fact, chosen.

This bill focuses on evaluating municipal actions in terms of their conformity with provincial plans and policies. It’s difficult to state how transformative that is. Currently in the city planning department, thousands and thousands of hours are spent at the Ontario Municipal Board—following council approval, following extensive consultation processes with the public—in order for one individual to fight to represent their specific interest. This is not a proactive way to plan a city or to plan a region. In fact, I would argue it’s an inherently problematic way. It is based on very narrow interests.

Our policy frameworks take into account the bigger picture. They look at how we are seeking to link together transit and transit densities with creating walkable, sustainable places. The vision for our region is clearly articulated through Places to Grow, with density targets.

We frequently have conversations with city councillors who will ask us, with respect to a specific proposal, about our success at the OMB: what we feel, as planners, will be achieved through the OMB process. Now, if we had a process that was driven primarily by policy, we could give a straight answer. But, in fact, we do something different: We frequently say to that councillor asking that question, “It will depend on the chair.” This demonstrates how this is not currently a quasi-judicial process. This is currently a process whereby unelected, unaccountable individuals make critical planning decisions that shape neighbourhoods. Despite living in Kingston, being appointed to your position, it might be possible to fundamentally transform a neighbourhood in Toronto.

My question to you today is this: How much does respect for democracy matter? It’s not just local democracy. It’s about democracy. It’s about accountability. The changes proposed in this bill represent a fundamental shift. They are a fundamental shift because they will change the way planning departments do their job. Rather than spending hours and hours writing witness statements and concocting arguments as to how to address a specific proposal, planning departments across this province will re-shift their efforts into creating the proactive planning frameworks that will shape and direct growth.

You might be afraid, and I’m sure you’ve heard today about a risk, that suddenly we will see growth stop. It’s important to note, first of all, that we are a pro-growth region in any scenario. The vast majority of applications that come forward through the city of Toronto are not, in fact, contested at the OMB. The ones that are have ripple effects and important implications, but the vast majority of projects are in fact in keeping with the provincial policy frameworks, with Places to Grow and are accepted by local communities as being an important part of creating a more sustainable region.

Some of the biggest, most significant and important developers in our city, like Westbank and First Gulf, don’t go to the OMB, and they don’t go to the OMB for a very important reason: They want to work collaboratively with communities and locally elected officials to create plans that are recommended and approved by city council.

One of the most recent and best examples to articulate this is the Westbank proposal for Bloor and Bathurst, or what you may know as the former Honest Ed’s site. A significant amount of density has been accommodated on this site, and it has been generated through a collaborative process with the community for a very simple reason: The developer made it clear that he was not interested in a fight. He wasn’t interested, from the outset, in going to the Ontario Municipal Board. He wanted to be a good corporate citizen. The community, in fact, rewarded him, and he rewarded the community with 28 heritage buildings that are now restored as part of that project, new park space and daycare on the site, and 20% affordable housing as part of that overall new development.

There was a collaboration that took place, as is always the case in our best city-building instances. That does not take place when a project gets punted to the Ontario Municipal Board. It’s a very difficult dynamic. At the Ontario Municipal Board it’s a bit of a crapshoot.

The opportunity with the changes that you see before you today is about reinforcing the importance of policy as being the way that we articulate in a democracy our shared objectives and what we are seeking to achieve. If you have a problem, take it up with the policy. If you have a problem, take it up with your local elected official, who will now be accountable. I’m sure you’ve heard stories of elected officials who don’t take responsibility for the decisions that are being made in their communities because they know it will be shunted off to the Ontario Municipal Board. That’s not a good way for us to plan our cities. It is better for municipal politicians to take responsibility for the decisions that they make and for the implications on the communities around them.

When we were undertaking our planning process for the Eglinton Crosstown, where 19 kilometres of LRT are currently being built, one of the things we heard loud and clear from the development industry was to put as-of-right zoning in place. This is a very important part of the narrative that needs to be understood, in this city in particular, so we did. So 25% of that corridor was transformed through as-of-right zoning, where you can now build an eight-storey building by pulling a permit; you don’t need to go through a community process because we did it all at once through the two-year Eglinton Connects process.

An interesting thing has happened that is one of the absurd outcomes of the OMB. The development industry said to us, “Give us as-of-right zoning,” and so we did. We want to see new development and intensification along our transit corridors. This is a critical part of combatting congestion. What’s happened is, even though we have in fact done so, we have seen developers coming back and asking for more. This is the speculative nature of development in a high-growth city that the OMB enables. If we create policy that’s based on sound planning principles, should that not be the policy that directs how we change and grow? The community really made a social contract in that process. They supported as-of-right zoning, recognizing that it was going to be compatible with the city’s guidelines around creating a walkable city, mitigating the shadow impacts. But, in fact, what we’ve seen as a result of the opportunity of an OMB that doesn’t currently respect the policy of local councillors is a whole industry that has been built on speculation. This is not in our best interests.

The Acting Chair (Ms. Cindy Forster): Thank you. We’ll start with Mr. Hardeman.

Mr. Ernie Hardeman: Thank you very much for that presentation. It was much appreciated. I think it’s consistent with a lot of the things we’ve heard from both the development side and from the municipal side that the OMB system is broken and needs to be fixed.

1710

I think in your presentation you pointed out that if you work together you can come up with the right decisions with the industry that wants to build and the municipality that wants it built. The developers told me today, the one group that was here, that they had only gone to the OMB once and the rest were all negotiated, but they said that the reason it was negotiated was because both sides realized that that was the best way to facilitate what should happen. That created tension in the system.

How do you envision that that would remain if there was no place to go, if there was nobody who had a risk of it going totally off the rails—“We have to come up with a compromise or it will go off the rails”? Could you comment on that?

Ms. Jennifer Keesmaat: Yes, thank you very much for the question. There are two answers that I’ll give in response to it. The first is that it’s important to recognize that the proposed changes to the OMB simply bring us in line with other jurisdictions across the country. They’re not radical; they in fact bring us in line with a more typical planning process. That’s the first.

The second is that I would argue that that question of negotiation should not be happening on a site-by-site basis with the lawyer and the developer for a specific project; it should be happening in the context of an area plan, where we create planning frameworks at the area plan level—like we did in Eglinton Connects. We in fact looked at the entire corridor, density targets for the entire corridor, the character of the corridor, and then put a planning framework in place to respond to that character, as opposed to the negotiation you’re talking about, which is really one specific interest. Many people are cut out of that process and are not at the negotiating table.

Mr. Ernie Hardeman: If I could, I talked to a major developer in Toronto—I’m not from Toronto—and that’s exactly the same thing he said about what was necessary: “We can accept whatever the community wants, but we need to know up front.” Most of the appeals that I’ve had concerns expressed about were density issues, the developers wanting more density and not being able to get it, and yet you say that the lack of density is the problem for creating that city that we want. I just wonder how we deal with that.

Ms. Jennifer Keesmaat: Well, one of the challenges that we face right now—and it’s important to note that in Toronto we have 19 corridors that are pre-zoned for mid-rise development. Let’s say that we never approve another application over the next 50 years. We’ll continue to grow at the rate that we’re growing at, because we have approvals in place along those mid-rise corridors. It’s very important to recognize that we already have an environment that can accommodate the significant amount of growth.

The Acting Chair (Ms. Cindy Forster): Thank you. We’re going to have to move on to Mr. Hatfield.

Mr. Percy Hatfield: Thank you for coming in, Jennifer. If I understand correctly, you’re enthusiastic about the bill and you see the future for planning based on policy or based on sound planning principles. You expect planning departments will re-shift their framework. Can you expand on that?

Ms. Jennifer Keesmaat: That’s correct. I believe that the way the bill is structured, where the emphasis is placed on ensuring that planning policy will be the driver behind decision-making, will in fact change the way municipalities plan, re-shifting our efforts from being proactive and reacting to applications to doing more secondary plans, area plans, neighbourhood plans that put in place the policy framework that clearly articulates what it is that we’re looking for.

Today, there’s a disincentive to putting those proactive plans in place. As I explained with Eglinton Connects, we put it in place, and because it’s a highly speculative environment, we simply got proposals for something different. But if we have an environment that uses policy to drive decision-making, it will in fact change the way municipalities plan.

Mr. Percy Hatfield: I think enough of us around the table have served a bit of time on municipal councils that we’ve seen how locally elected officials sometimes play the board politics, but I’m encouraged by you saying that local elected officials will now have to take more responsibility for their decisions. Will that, through this bill, again, make better, sound planning policy?

Ms. Jennifer Keesmaat: Absolutely. It’s also a critical part of democracy. Currently we have people making decisions who have no accountability. In fact, the public doesn’t even know who they are. They can’t be voted out; they’re not held accountable for the mistakes that they made.

The whole dynamic of democracy is that it must happen in a transparent environment—that you must take accountability for the decisions that you make as an elected official. You must defend those decisions; you must believe in those decisions. I believe that the way this is now structured reinforces municipal politicians ensuring that they have their eye on the policy. Right now, you can be kind of flippant about policy because you know that someone you don’t know is going to make a decision behind closed doors and they’re going to accountable for it. I think that is a very dangerous way for a democracy to make decisions.

The Acting Chair (Ms. Cindy Forster): Thank you.

We’re going to move on to the government member: Mr. Rinaldi.

Mr. Lou Rinaldi: Thank you, Ms. Keesmaat, for being here today. Wow, the power and the enthusiasm you have—it’s overwhelming. Thank you for the work you did for the city of Toronto. I lived some part of my life in Toronto; I don’t anymore, but certainly I was here.

Anyway, back to Bill 139: I think the comment that you made along the way was that Bill 139 proposes fundamental changes to the way we plan, and it’s a different way for municipalities or elected officials—and staff—to deal with the planning process.

What do you think the greatest impact of these changes might be to a community—not necessarily Toronto, but in general?

Ms. Jennifer Keesmaat: I believe the greatest impact is that there will be an opportunity and a re-engagement by communities in the planning process, precisely because policy will become a key driver in how decisions will be made. That will be good for our cities; it will be good for democracy.

I’m not concerned about NIMBY constraints that you may have heard about today, for the two reasons that I stated: (1) We have so much that’s already approved, and (2) because we’ve overwhelmingly seen that we are a pro-growth region. We see the value of growth, and the vast majority of projects, even with the OMB playing the role it does today, have gone forward completely unappealed.

Mr. Lou Rinaldi: I’m not sure if you were here today, or even the other day when we were here. We’ve heard from some sectors that if Bill 139 were to go through, we won’t see any more development; we won’t see the density that’s needed to support transit; and we won’t see more affordable housing. How would you help us defend that?

Ms. Jennifer Keesmaat: It’s really, really important to go back to what has already been approved, and the provincial policy framework. The provincial policy framework would prevent that from happening. If local councils said, “We want no growth,” they would lose at the OMB, because they have a provincial policy framework in places that grow that already makes it clear where they are to accommodate growth. The policy actually works both ways. It works to promote growth.

In a corridor like Eglinton, I believe one of the positive outcomes is that we would see developers building according to the policy framework we have put in place. Right now, I have developers that come to me and say, “You up-zoned to eight storeys. I want to build an eight-storey building. I go to bid on a piece of property, and someone comes in and bids way more money. I want to build what the policy allows, but someone who is speculating, who is taking a gamble that they can make more money by asking for more than they’re permitted, is outbidding me. I want to build mid-rise buildings, but I’m getting bumped out of the process because of the way speculation works in the system.” I believe this will reward developers who want to build mid-rise development in the city of Toronto.

I was just in Auckland recently, and a mid-rise building in Auckland is four storeys. We’re very generous in Toronto; it’s anywhere between eight and 12. In most cities, that’s considered a tall building.

The Acting Chair (Ms. Cindy Forster): The time is up.

Mr. Lou Rinaldi: Thank you.

The Acting Chair (Ms. Cindy Forster): Thanks very much for your presentation.

Ms. Jennifer Keesmaat: Thank you.

1720

[End]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!