Everybody’s story matters: Speaking notes for Sept. 1, 2018 Nordic Meeting (for people who stutter) in Tallinn, Estonia

Update:

A second post, regarding this talk, is entitled:

Draft No. 2 of speaking notes: Sept. 1, 2018 Tallinn talk

[End]

Between 1988 and 2003, over a period of 15 years, I did a lot of volunteer work on behalf of people who stutter. Sometimes, I would work at this night and day. These days, I almost never work that hard.

Since 2003, my volunteering has been largely concerned with other matters. However, I still do some volunteer work concerned with stuttering. At least once a year, I give a talk at an elementary school in Toronto, telling about my own childhood experiences, as a person who stutters.

By telling my own story I can, in a small way, change public attitudes and dispel myths about stuttering. Telling our own stories, as people who stutter, is one of the ways we can change attitudes.

People like stories, because they engage our emotions. Sharing of factual information, without storytelling, is often less effective – because the emotional connection may not be there.

My own preference is to tell stories that are evidence-based, as contrasted to stories that are made up, or based solely on opinions.

I will speak at a meeting in Tallinn on Sept. 1, 2018

What follows below are speaking notes for a presentation at a Nordic Meeting – of people who stutter from Scandinavian countries including Estonia – in Tallinn, Estonia, on Sept. 1, 2018. Some (maybe most; I don’t have any details about this) Estonians like to position themselves as Scandinavians, instead of Eastern Europeans.

My previous visits to Estonia were in 1989 and 1990, at a time when Estonia was still occupied by the Soviet Union. In the summer of 1989, I did volunteer work in Estonia with an Estonian heritage society.

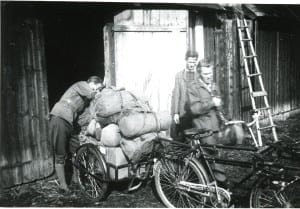

Estonia, Summer of 1944: My parents and other family members escaped from Estonia to Sweden, in separate boats across the Baltic Sea, in September 1944 during the second Soviet occupation of the Baltic states. Click on photos to enlarge them; click again to enlarge them further.

Even though I was dressed like everybody else in Estonia (instead of as a typical Western tourist) during my visits, people often told me they could see at once, that I was from the West. They noticed, among other things, that I wasn’t looking back over my shoulder, to see if anybody was following me.

Estonians I met also remarked that I spoke Estonian without a Western accent.

One person remarked, as well, that it was great to encounter a visitor from the West, who spoke Estonian as it was spoken in the 1940s.

My parents, and other members of my extended family, had fled Estonia as refugees in 1944, at about the time that Soviet forces were bombing the city of Tartu, during the Second World War.

I was born in Stockholm, Sweden after the war had ended. We spoke Estonian at home. That accounts, at least in part, for my lack of a Western accent. It also accounts for my language usage. I learned to speak Estonian in the late 1940s. That’s the only way of speaking, in Estonian, that I have ever known.

People like to hear stories; abstract concepts are of less interest

In the first 20 minutes of my talk in Tallinn, I will tell my own story, as a person who stutters.

As a speaker at conferences, I’ve learned it’s often a good idea to say a few things about myself, as a person who stutters.

Boat on which my father and grandfather and other refugees sailed across the Baltic Sea in September 1944 during the Second World War. Other family members travelled across the Baltic on a larger vessel.

In my talk on Sept. 1, 2018, I will refer to a brief outline, with key points, from my speaking notes, during the talk. The speaking notes are helpful, however, in organizing my thinking, during the planning stage.

During my first visit to Estonia in 1989, I met Ülo Lomp, who was involved with the organizing of the heritage work – the renovation of a manor building – that I was involved in. During my visit, Ülo Lomp also arranged for me to be interviewed by an Estonian reporter.

In the interview, I spoke about my volunteer work on behalf of people who stutter. The heading for the resulting magazine article was along the lines of: “We have a lot to learn from each other.”

After the article appeared, I was invited to deliver a series of lectures, in Estonian, at a children’s clinic in Tallinn, in the summer of 1990.

In those lectures, I described Western approaches to the treatment of stuttering. I also described a three-week stuttering treatment program that I had attended in Edmonton in July 1987.

Before the lectures, I met with another Estonian friend, Andres Loorand. Andres helped me with translation of technical terms, related to stuttering treatment. That was very helpful. It’s also as a result of an invitation, from Andres Loorand, that I am speaking in Tallinn on Sept. 1, 2018.

After I spoke in Tallinn, in 1990, an Estonian who stutters made a comment, which moved me deeply.

He said, “It really means something to us, that somebody from the West would actually have a concern about those of us who stutter, in Estonia.” I could relate perfectly, to what he was saying. It’s so valuable, when somebody has a concern, for those of us who stutter.

Boat on which my father and grandfather made it across the Baltic Sea in September 1944. My grandfather is on the right, in the photo.

Another person, who helped to organize the heritage work, that I took part during my first visit in 1989, I also met Aare Hindremäe. I have kept in touch with him, and with Ülo Lomp and Andres Loorand, ever since. All of us, of course, are a little older now.

Text of my speaking notes

I want to thank you for the opportunity to speak with you today. It’s been a while since my last visits to Estonia, which took place in 1989 and 1990. Much has changed in Estonia since then.

The title of my talk is: “Everybody’s story matters.”

I chose the title because each of our stories is equally important.

I’ve been involved in volunteer work, on behalf of people who stutter, for 30 years. In the first 15 years, from about 1988 to 2003, my focus was on community organizing on behalf of people who stutter.

As it turned out, I was the right person, at the right time, and at the right places, to help out with the founding of several national and international stuttering associations.

I will begin with my own story as a person who stutters.

I began to stutter at the age of six, in 1952. By that time I was living in Montreal.

My parents had fled Estonia as refugees in 1944. I was born in Stockholm in 1946. We travelled to Canada in 1951 when I was five years old. The next year I began to stutter.

When I was in elementary school I received some speech therapy, but it didn’t help. Sometimes when I tried to speak, no words would come out at all. I spent much of my time not saying anything.

In those early years, when I could barely speak, a most amazing thing would sometimes happen. Every once in a while, a person would look at me, and through a smile or gesture, would pass along a very important message. That message was: “Yes, you stutter. Nonetheless, you are a cherished, and valuable, part of the human race.” These small, but in fact also major, acts of kindness have always stayed with me.

The phone call that never got off the ground

I remember an event, in my late teens or early 20s. One time, in those years, I wanted to phone someone, and speak to them.

So, I picked up the phone, and in those days, the “H” sound was very difficult for me to say. Words like hello, house, or holiday: Sometimes, I just could not get past the “H” sound.

So, on this occasion I picked up the phone, and I wanted to speak to someone, and I wanted to say hello. And so, I tried to say hello but I could not, and for maybe 20 or 30 seconds there was a period of silence, on the phone line, and after that, I decided to hang up the phone.

I still remember the feeling: “Here I am, at the beginning of my life. My life is stretching out ahead of me. I pick up the phone, and I can’t even say hello.”

So, that was part of my experience, as a speaker in those years, but at the same time we know that the severity of stuttering can vary from situation to situation, and from time to time.

We also know, from anecdotal evidence, that some people who stutter severely have become very successful as actors, or singers, or other kinds of performers.

This has to do, perhaps, with taking on a particular role. It also has to do, perhaps, with having a prepared script, and enough time to rehearse one’s lines. In such a performance, a person usually has good control over her or his breathing. When we can breathe smoothly, we can often get the words out.

High school election speeches in 1962

And so, another story that I want to share concerns the time that I was in high school in grade 10, and we heard in our school of a call for nominations, for anybody who wanted to try to get elected, as president of the student council.

A friend of mine, who I think was very perceptive, had observed that sometimes, I had been very outspoken in our English classes. That gave him the idea that I would make a good president, of the student council. That is, on some occasions, it was clear I had opinions and liked to speak out.

The reason I was outspoken in English classes was that I had learned, as a person who stutters, that if I interrupted our teacher, while he or she was talking, I could sometimes achieve some level of fluency. At other times in class, I would just get stuck, in trying to say a sentence, and not get anywhere. It also happened that I was a first-rate English student. I was among the best students, of English literature and composition, at the school.

So, my friend said to me, “Why don’t I nominate you as president of the student council?” I thought, “Why not?”

So, I was nominated, and as part of the election campaign, the two candidates, for the presidency of the school council, had to give campaign speeches in the school auditorium.

It was a big auditorium, and could seat hundreds of students. There would be two such speeches, so that as many students, as possible, could hear the two candidates make their speeches.

And so, as a person who usually stuttered severely, I was wondering what I should do. I decided that I would write a great speech, using the inaugural speech (made in January 1961) of the American president, John F. Kennedy as a starting point.

I would use Kennedy’s inaugural speech as a model, for crafting my own campaign speech.

At that time, we lived in a small, two-storey house in Montreal, and I would stand at the top of the stairs, on the second floor, and would rehearse my speech every day, while no one else was at home. Day after day, I would keep on rehearsing my speech, until I had it memorized.

Finally, the big day arrived, at the school auditorium.

I recall that, the first time that I gave my speech, I was walking down an aisle, toward a stage where a lectern and microphone had been set up. As I was walking toward the stage, some of the students looked at me, with expressions of concern and alarm.

They knew I stuttered severely. They were not at all keen to witness what, as they feared, was about to occur.

I stood on the stage, looked at my written text, and announced that I would be making no promises, in my campaign for the presidency. I said, and I quote, “In your hands, instead of mine, will rest the final success or failure of the student council.”

It turned out to be a great speech. I spoke fluently, I think because I had rehearsed my speech endlessly, and because I managed to maintain a smooth rhythm, in my breathing. I made the speech, using the strong cadences and turns of phase, that the American president John F. Kennedy, would have used.

So, I finished my speech. There was a moment of silence. And then I heard a tremendous round of applause. On a subsequent speech, I made the same speech. Once again, I heard a tremendous round of applause.

Soon it was confirmed that, as I had expected, I had won the election by a landslide.

I’m still friends, these many years later, with the person who was my opponent in the election. We both have leadership qualities.

Speaking at other times was a struggle

Despite my great speech, at the auditorium at my high school, most of the time it was a real struggle for me, to get out any words at all.

I had no idea what kind of work I would be able to do, as an adult, given that I could barely speak, much of the time.

Eventually, after many years, I managed to complete a bachelor of arts degree, at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, on the west coast of Canada.

After university, I began working with very young children, as a substitute teacher at a day care centre in Toronto. By a chance conversation, with someone I met at the day care centre, I learned that, as a university graduate, I could also do supply teaching in special education schools, that existed at that time in Toronto, for severely handicapped students. The classes were small, and the fact I stuttered was not a concern for anybody.

Speech therapy in Toronto in 1976

At the age of 30, I attended a speech therapy clinic in Toronto. This was a three-week clinic, where for the first time, since the age of five, I learned that it was possible for me to get through a full sentence, without struggling over any of the words.

When I achieved that feat, of saying a full sentence without a struggle, a voice inside me said, “You were very close to losing hope, that you would ever be able to do this. You’re not supposed to give up hope!”

After the clinic, I spoke quite well, although I was not prepared to engage in public speaking.

About a week after I had attended the Toronto clinic, in 1976, I was talking with a friend on the phone, and all of my newly acquired fluency skills flew out the window. All of the old ways of speaking seemed to return. It was like I was watching a flock of birds, flying away from me.

Despite this setback, however, I still was able to speak slightly more fluently, than had been the case previously.

As a supply teacher, working in special education classes, I realized that it would be a good idea for me to take a one-year course, at the University of Toronto faculty of education, in order to get a teaching certificate.

After a lot of hard work, I graduated from the program, and got a full-time contract as special education teacher. I still stuttered, but I had a job as a teacher.

May 4, 1987 Toronto Star article

At the age of 41, I read an article in the May 4, 1987 edition of the Toronto Star. That article, which described a newly opened speech clinic in Edmonton, Alberta, changed the trajectory of my life. I would not be speaking with you today, had I not come across the article. I still remember the chair where I was sitting, in an apartment in Toronto, across from the school where I was working.

The clinic was called the Institute for Stuttering Treatment and Research, or ISTAR for short. These days, I make regular donations to ISTAR, in support of their work.

I was on the phone, speaking to staff at ISTAR, the next day. In July of 1987 I flew out to Edmonton, to attend the clinic. I like to say that, at the clinic, I relearned how to speak. I can also say that I learned fluency as a second language. I learned a set of five speech skills, and I practised them each day, once I was back in Toronto, for a period of time that lasted over four years.

The skills that are taught, at the clinic, are continuously changed, in small ways, based on research and clinical experience. The skills that I learned, over 30 years ago, have worked really well for me.

Having taken a three-week program, at age 30 in Toronto, I knew how easy it is for a person to lose the skills, that’d been learned at a clinic. I made sure I would do a great job of maintaining my skills, by consciously applying them each time I spoke, as the years went by. That took a lot of work, and it has paid off well for me.

On rare occasions, my speech does tighten up a little, even now, but I always know exactly what to do, to ensure that the words continue to flow, more or less smoothly.

YouTube video

Not everybody who stutters is going to end up at a three-week clinic, of the kind that I attended in 1987. Some people can make great progress, in their speech, just by being open about stuttering, and getting large amounts of practice in public speaking. One of my friends, Arun Khanna of Toronto, has achieved great results, without getting much in the way of formal speech therapy at all.

I say that, to underline that there are many ways, that a person can choose to deal with stuttering. Each of us can choose our own way. There is no one way that will work for everybody.

Some time back, I recorded a 90-second video, and posted it to YouTube. In this video, I briefly interviewed Arun Khanna, at a meeting of the Canadian Stuttering Association (or CSA for short). The video is of value for two reasons.

First, it provides a transition, from highlights about my own story as a person who stutters, to highlights about my role, in the founding of several associations for people who stutter, in Canada and elsewhere, in the 1990s.

Secondly, Arun’s testimonial, regarding the benefits that he’s received from being an active member of the Canadian Stuttering Association, speaks for itself.

Bothersome inner voice

The second stage, of my presentation today, involves how I became involved with community organizing.

After I got back from Edmonton, I began to make presentations to large audiences.

After the Edmonton clinic, however, I also began to run into a huge problem, which I had never expected, and which bothered me no end.

Each time that I would be making a presentation to a large audience, a voice inside me would say, “You’re not supposed to be able to do this. You’re supposed to be falling flat on your face.” Each time I was speaking to a large audience, the same inner voice would start to bother me.

I would talk about this with one of my friends, who did not stutter. My friend would say, “You’re now doing a great job at speaking. So, why would this inner voice now be a source of concern for you?”

At first, I thought that I should get some psychotherapy. But then, an even better idea occurred to me. I realized that, what I needed to do was to talk with other people who stutter, and compare notes with them. That would be the best way, I realized, to deal with this bothersome inner voice.

So, I decided to form a self-help group for people who stutter, in Toronto. I spent several months speaking with people, to get ideas about how best to go about launching such a group.

One of the people that I spoke with said that he had seen plenty of such groups come and go, over the years. Once the founder of the group got burned out, or moved on to other things, the group would fold.

I decided that, with the group I was starting, that would not happen. Instead, I decided that, from the start, we would focus on leadership succession. When we formed this Toronto group, at a meeting in September 1988, we called it the Stuttering Association of Toronto, or SAT for short. We met every two weeks, and I led the first few meetings. After that, we arranged for other people to take turns, if they wanted to, in leading two meetings in a row. In that way, we all got leadership experience – and developed a strong sense of shared ownership, of the association.

I had also seen meetings of groups, for people who stutter, where one or two people would do most of the talking. I decided that, in the group I was involved with, speaking time would be shared more or less equally. That’s a way of saying that everybody’s story matters.

I had also seen a group where the members were all clients of a particular treatment program. If you hadn’t been through the program, you couldn’t join. I wanted to start a group that was open to everybody, whether they had encountered speech therapy or not. As well, friends and family members of stutterers would be free to join the group. In addition, our group would offer an impartial forum, for the sharing of information about stuttering. We would not advocate on behalf of any particular approach, for dealing with stuttering.

The one thing that would be off-limits would be claims for sure-fire “cures” for stuttering. We were not going to provide a forum for so-called treatments, that could not be backed up by solid evidence.

We also decided that the group would be run by people who stutter, not by speech therapists. Speech professionals were welcome to attend meetings as guests, but they were not going to be involved with the running of the group.

Several other thoughts occurred to me. I knew of a group where leaders had impressive titles, such as president, and where the group structure was very hierarchical. For some people, power just goes to a person’s head, and they can become very domineering, and difficult to work with.

We also did not want a situation where one person does all the work, makes all the decisions, and eventually drives all of the other volunteers away, until the group folds. That was not the kind of group that we had in mind, when we founded the Stuttering Association of Toronto.

I also decided that, in the group I was starting up, an informal, flat-hierarchy structure would be in place. To underline this, instead of calling the leader of the group the president, I suggested that the leader be called a coordinator. That’s a less impressive title, and more in fitting with a flat-hierarchy structure.

Adjusting to changes, that have occurred in a person’s life

After about a year of meetings, of this group, a speech therapist who stutters, named Tony Churchill, came to speak at one of our meetings. After the meeting, I asked him about this inner voice, that kept on telling me that I should be falling on my face, each time I spoke to a large audience. Tony knew at once, how I could address the inner voice. He said to me, and I paraphrase: “What you’re are dealing with is the need to adjust to some changes, that have occurred in your life.”

I said to myself, “Wow! That’s it. That’s what the inner voice has been telling me.” From that point on, the inner voice never bothered me again.

First-ever Canadian national conference for people who stutter

After about a year of meetings, those of us who were active, with the Stuttering Association of Toronto, began to work with other groups across Canada, to organize the first-ever national conference of self-help associations, of people who stutter. We spent two years organizing the conference, which took place in August 1991 in Banff, Alberta.

I worked with many other people to create a draft of a constitution for the new national group, which eventually became known as the Canadian Stuttering Association, or CSA for short. We had input from people across Canada, as we developed the association’s bylaws and constitution. Instead of a president, to lead the association, we had a national coordinator. That person would serve for two terms, of three years each, as I recall. Then a new national coordinator would take over.

As well, we would offer an impartial forum for the sharing of information. We would collaborate closely with speech professionals and researchers, but would be independent of them.

CSA has done very well, in the years that followed. I served as the first national coordinator, and since that time, a whole series of great leaders has taken on the role, of serving as the national coordinator. We have an informal structure, and input is welcome from every source. We never have a situation where just one to two people run the show.

When work has to be done, to organize national conferences and events, or develop an annual strategic plan, the work gets done smoothly, in a collegial atmosphere.

We don’t spend a lot of time dwelling on our early history. The culture of decision making, that was in place at the beginning, is still in place now. Our focus, as a national association, is on the present moment. We are always seeking new blood, to join the leadership team that is currently in place. We are always seeking ways to ensure that growth and renewal is at the forefront, of all of the work that CSA does, on behalf of people who stutter across Canada.

In my case, I’m a member of an advisory board, at the association, but I do not have a vote, when the board of directors makes decisions. That’s because it’s been many years, since I was on the CSA board of directors. I keep in touch with decision making, but primarily as an observer, viewing things from the sidelines.

The culture of decision making, that I have described, is a culture that has worked well in Canada, with input from many Canadians including myself. I would not say, for a moment, however, that what works for us in Canada is the only way to organize, at the national level.

Every country is different. Every country has a different culture. About all that I would want to say is that, as people who stutter, we have a lot to learn from each other. Speaking for myself, I do not see myself as an expert, regarding any topic.

I want to add, as I like to be accurate about things, that in time the Stuttering Association of Toronto folded. I eventually moved on to other things. Other people kept in running for some time, but eventually it folded. Indeed, such groups tend to come and go.

Larger groups, such as national associations for people who stutter, tend to stay around for longer periods. There’s usually people around, with an interest in volunteer work, to keep it going. As well, in some cases national associations find a way to pay for an executive director and perhaps other staff. That is an arrangement that can be particularly effective.

Launch of the Estonian Association for People Who Stutter

One of my interests, in visiting Estonia this year, is to learn details about how the Claudius Club was launched, after my lectures in Estonia in 1990. I also have an interest in learning what steps were involved, in the launch of the Estonian Association for People Who Stutter. As I recall, the launch occurred around 1993. The English version of the Estonian associations’s name, I would note, is similar to the original name that we had for CSA.

Originally, the name of the Canadian association was the Canadian Association for People Who Stutter, or CAPS for short. Eventually, however, it occurred to me that, for the benefit of media outlets, reporting about our activities, it would be better if we had a shorter name. For that reason, some years ago, I suggested to the board of directors that the name, Canadian Stuttering Association, would work better than the longer name, that we had started out with. The board agreed with my suggestion, and we’ve called ourselves the Canadian Stuttering Association ever since.

Launch of the International Fluency Association, and of the International Stuttering Association

I was not involved with the launch of the International Fluency Association (IFA), but served for some time, around the early 1990s, as chair of the IFA’s support groups and consumer affairs committee. I also organized a panel discussion, featuring self-help groups and speech professionals, at an early IFA congress. Some years later, I made a keynote presentation at still another IFA congress, about things I had learned about the dynamics of national associations for people who stutter.

The IFA sought to bring together speech professionals, researchers, and people who stutter, all in one body. My sense was that, in practical terms, people who stutter were the junior partners in this arrangement. After some years, I was approached by Thomas Krall of Germany to launch another international body, the International Stuttering Association, which would serve as a voice for people who stutter, at the international level.

Again, I was involved as a key organizer, for the launch of this association. Along with Thomas Krall and other self-help leaders from countries around the world, we sought input from all interested national associations regarding the constitution, bylaws, and formal launch of this new international body. Among the provisions, in the constitution, was a formal policy of leadership succession, and the provision of an impartial forum, for the sharing of information.

For some years, I was active with ISA in an advisory capacity, offering input when the board of directors was exploring a wide range of options, in the early years of its growth. For a while, I also served as chair of an outreach committee that was involved in assisting in the launch of new associations in countries such as Israel, China, and several African countries.

In time, I stepped back from my volunteer work at the international level, and spent several years assisting CSA with organizing of conferences, and with media relations.

In the past 15 years, as I’ve noted, my volunteer work has largely been focused on areas other than stuttering. Nonetheless, I find it of much interest, to look back on what has been achieved in the early years, and to share some reflections, regarding what I have learned.

Acknowledgements

I want to express special thanks to Steve Nazar, now living in British Columbia, for help with the preparation of these speaking notes. Steve has not had any involvement with stuttering, but was intrigued to learn about my upcoming talk in Estonia.

In the past week or so, Steve and I have exchanged emails, regarding the content of my Sept. 1, 2018 talk in Tallinn. Steve has shared valuable suggestions, especially with regard to ensuing that I speak about what prompted me to advocate leadership succession, a flat hierarchy, an impartial forum, and the like, in the course of working to launch several stuttering associations. These suggestions have significantly enhanced the quality, of the final versions of the text.

All well done Jaan. I don’t know if you remember the summers our families spent together with the Timtschenkos and later on Isle Bizzard, Christmases together, visiting you at skaudi laager, etc.l You’re 4 years older than me but you became my childhood hero. I learned so much from you. Because you were my hero I wanted to do all the things you did and to emulate you. I even began to stutter, so I could be like you. I don’t ever remember you not being able communicate with me and I never realized how big a problem this was for you. I only remember you being able to talk with me and my parents. They were best of friends with your parents. It took some time for my parents to work me out of stuttering but they did. Obviously they knew how big a problem this was for you and did not want me to suffer the same burden. I still have all the respect in the world for you and am glad that you were an integral part in the shaping of my life. Thank you and much love.

Peeter

Wonderful to read your message, Peeter. I did not know that I could serve as a role model, but now I can see the possibility, given your description. That is most interesting, to know about the most interesting perspective, that you have shared in your comment, regarding childhood events and times of many years ago. Your comment is really helpful, in enabling me to get a more detailed, more comprehensive understanding of childhood summertimes and events of many years ago.

I’m pleased that you grew out of your stuttering. About 5 percent of children stutter during the years when they are acquiring speech. Most outgrow it; about 1 percent of adults stutter.

I remember Ile Bizard and the summers before. We still have some photos of a house that our families rented on Ice Bizard. I also remember the last time I saw your parents, before they passed away. They visited at my parents’ cottage (it’s since been sold) on Fraser Lake in the Quebec Laurentians, one summer some years ago.

My Dad had much enjoyed the cottage, with its trees and water. It gave him a sense of peace and solace that, for an emigre Estonian, in his case no other resource could provide. He used to say (and I paraphrase), “The cottage is like a little bit of Estonia, for me.”

On that final visit to the cottage in the Laurentians, your Dad remarked (and, again, I paraphrase), “Jaan, you are one of those people, who hasn’t changed at all, with the passage of the years.” It was good to speak with your Mom, as well, on that occasion. The last time I saw your parents was when they drove away (your Mom was driving the car), on the unpaved roadway leading away from the cottage on Fraser Lake.

I’m really pleased, as well, that Gina Cayer, who played a key role helping to organize a Sixties Reunion for Malcolm Campbell High School, that took place in Toronto in 2015, has told me of her close connection with your family through a friendship dating back to the Ahuntsic days.

I’m really pleased to be keeping in touch with you! As I understand, you’ve been living in Vancouver for some years. I was there in the late sixties and early seventies, when I was a student at Simon Fraser University. I also travelled all over British Columbia. It’s a beautiful province, where I had many memorable experiences:

TRCA/Sawmill Sid portable sawmilling project is now underway at Small Arms Building in Mississauga

If I am ever back in B.C. for a visit, I would much enjoy meeting you, once again. Alternatively, if you are out visiting in Southwestern Ontario, at any time, please let me know. My email is jpill@preservedstories.com

Best,

Jaan

Hi Jaan, so lovely to come across your post tonight. I met you through your brother Juri way back in the late ’60s or early ’70s, and we shared a dinner at my wee 3rd floor flat on Playter Boulevard in the Broadview Danforth area then. Also, I believe we shared a lift to Metsaülikoor at about those years by from parents who delivered us to Kotkajärv. Just wanted to say hi, and to say how interesting it has been to read your story here.

Are you still based in Toronto? I used to pass a place just east of Lesmill before I retired several years ago, that was called something like the Cdn. Stuttering Assoc., or so., and always thought of you then.

Take care, and all the best with your good work!

Hi Marje, wonderful to read your message. I’m pleased to look back to those years, and I’m pleased you found my story of interest.

Our family has recently sold our house in Toronto. We will be living outside of Toronto but are still in close touch with friends and resources in the GTA. I now serve as a foreign correspondent, so to speak, with regard to local history and cultures of land-use decision making along the GTA waterfront:

I now serve as foreign correspondent, blogging on land-use decision making along the Lake Ontario waterfront in the GTA

I’ve been retired since 2006 from a teaching career of 30-plus years.

It was interesting to read your reference to the Canadian Stuttering Association. The association, run entirely by volunteers, was founded in August 1991 at a conference in Banff, Alberta, and is still going strong. I was closely involved with CSA in its early years. The association is still going strong, with new generations of leaders serving as key volunteers, as the years and decades come and go.

Yesterday, at Tartu College, I interviewed the archivist (and history enthusiast) Piret Noorhani, regarding the great work that Estonians are doing, outside of Estonian and within the country itself, with regard to preserving oral histories, books, photos, documents, and digital resources.

I much enjoy learning about all the great things that people (of all nationalities, around the world) are doing, with regard to preserving great stories (every story matters, in my view!) from the past.

Best,

Jaan