History begins with definition of terms

At a recent post, I began to write about my approach, as a layperson, to reading about history:

In his 2015 article, Kasekamp comments (p. 156):

“Using Stanley Payne’s typology of fascism [3], I have previously argued that it is more appropriate to describe the vaps movement as ‘radical right’ rather than ‘fascist’[4]. In this article, I hold nevertheless that there is some ground for including the vaps movement in the category of ‘generic fascism’ as defined by Roger Griffin and the ‘new consensus’ in fascism studies [5].”

Precision in terminology, and with regard to language usage in general, is from my perspective a key feature of high-quality nonfiction writing.

A Jan. 10, 2019 Guardian article, entitled “‘We the people’: the battle to define populism,” is of interest, with regard to the ongoing quest in Western society for precision, in the use of language, with regard to terms such as populism and fascism.

An excerpt from the article reads: “In what way are Occupy Wall Street and Brexit both possible examples of populist phenomena? Mudde’s simple definition caught on because it has no trouble answering this type of question. If populism is truly ideologically ‘thin’, then it has to attach itself to a more substantial host ideology in order to survive. But this ideology can lie anywhere along the left-right spectrum. Because, in Mudde’s definition, populism is always piggybacking on other ideologies, the wide variety of populisms isn’t a problem. It’s exactly what you would expect.”

As a follow-up to the above-noted post about 1930s Estonia and Europe, I have bought a copy of The Radical Right in Interwar Estonia (2000) by Andres Kasekamp. I know it will be a good read, because I’m interested in the topic, and I’m impressed with the author’s other work.

High intensity interval reading of history

Every few months since 2012, I’ve borrowed a good number of books from the Toronto Public Library and read them. Then for a few months I would not take out any library books at all. After such an interval, I would again take out as much as fifty books at a time, and spend time reading them. Over the years, I’ve maintained such a recurring cycle of intensive reading, followed by months when I wasn’t taking out any library books at all.

View of Lake Victoria in Stratford. The shoreline of Tom Patterson Island is visible on the left in the background. Jaan Pill photo

I am absolutely astounded by how much I’ve learned, since starting to read intensively about world history starting in 2012.

The process is akin to learning a new language, or learning to play a musical instrument, or to ride a bike.

I have attained a better understanding, about how first-rate professional historians go about their work, and how a layperson, such as myself, can gain tremendous benefit from the focused and systematic study of texts published by outstanding historians, of which there are many.

Criteria for assessing usefulness of a text

For books about history and related topics, my first criterion concerns how an author deals with evidence.

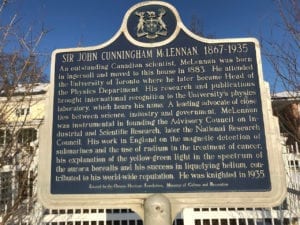

Plaque in celebration of local Stratford citizen, the Canadian physicist John Cunningham McLennan, who contributed to his chosen field in a huge way. Jaan Pill photo

My interest in evidence, and evidence-based practice, developed several decades ago. Before that, evidence as a criterion for making sense of things didn’t matter much to me. What mattered was my opinion, and I was always prepared to defend it vigorously.

I now ask myself: How well acquainted is a given author with evidence in a given field, as compared to other authors?

For a given subject area, such as Eastern Europe in the twentieth century, is a given author closely acquainted with the majority of archival and secondary sources, or are there gaps?

I look, as well, at the frame of reference, that an author uses to structure a research report or overview. Is it balanced or is it slanted?

If an author’s handling of evidence isn’t up to scratch, or if the frame of reference is strongly slanted in terms of ideology or some other strongly held belief system, I may check out some of the bibliographical citations. But I will not end up quoting from such a book, or spending a lot of time reading it.

Whether a given book is widely read, as evidenced by an appearance on a bestseller list or is not widely read, is irrelevant from my vantage point, with regard to whether or not the book warrants close reading.

As well, the author’s tone of voice will influence whether or not I will read a given text at length. I prefer a tone that is not characterized by vehemence, and by attempts, page after page, to direct the reader’s emotional response and judgement. I prefer to encounter a measured (as contrasted to polemic) marshalling, organizing, and presentation of evidence – in which the emotional response and judgement that arises, from the evidence, is left up to the reader.

Bird’s-eye view and view from the trenches

Some historical studies, which take a bird’s eye view of history, focus on high-level decision making by political and military leaders. Other accounts focus on experiences of civilians and combatants (military or irregular) at the frontline, or in terms of events of everyday life.

Both vantage points are of interest and value, and complement each other. Books in each of these two separate categories offer valuable overviews of historical events and processes.

As well, local history is closely connected to world history. When I look at local history, I’m always keen to learn about the wider historical context, inside of which local history is embedded.

Local history is closely connected to world history including the history of art, music, and drama. It is also closely connected with world environmental history.

Two of the most exciting stories related to local history, that I’ve come across in Canada, outline the tremendously valuable contributions that Tom Patterson in Stratford, and Jim Tovey in Mississauga, have made on behalf of – and in close collaboration with – their respective Ontario communities.

A previous post regarding Patterson and Tovey is entitled:

Texts of plaques featured at this post

I’ve illustrated this post with photos from Stratford, where we have lived since Oct. 25, 2018. We sold our house in Toronto on July 23, 2018 and travelled across Southwestern Ontario and parts of Europe and Scandinavia, while waiting to purchase the kind of house that we were keen to buy in Stratford. We found the house, with the features we were seeking, and have now settled in. We are delighted to be living in Stratford – and Toronto remains for us a great place to visit.

As with most photos at this website, you can enlarge them by clicking on each image.

I have not double-checked, by way of proofreading, the texts that follow. The definitive text is in the photos on which the texts below are based.

The plaques read as follows [in some cases I’ve broken longer texts into shorter paragraphs, for ease of online reading]:

Re: Tom Patterson Theatre Centre

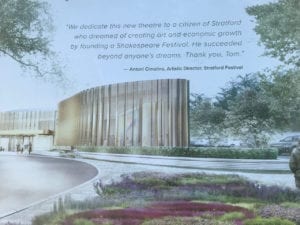

Quotation accompanying artist’s rendering of the Tom Patterson Theatre Centre:

“We dedicate this new theatre to a citizen of Stratford who dreamed of creating art and economic growth by founding a Shakespeare Festival. He succeeded beyond anybody’s dreams. Thank you, Tom.”

– Antoni Cimolino, Artistic Director, Stratford Festival

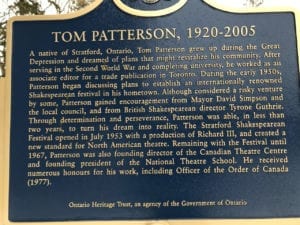

Tom Patterson, 1920-2005

A native of Stratford, Ontario, Tom Patterson grew up during the Great Depression and dreamed of plans that might revitalize his community. After serving in the Second World War and completing university he worked as an associate editor for a trade publication in Toronto.

During the early 1950s, Patterson began discussing plans to establish an internationally renowned Shakespearean festival in his hometown. Although considered a risky venture by some, Patterson gained encouragement from mayor David Simpson and the local council, and from British Shakespearean director Tyrone Guthrie.

Through determination and perseverance, Patterson was able, in less than two years, to turn his dream into reality. The Stratford Shakespearean Festival opened in July 1953 with a production of Richard III, and created a new standard for North American theatre.

Remaining with the Festival until 1967, Patterson was also founding director of the Canadian Theatre Centre and founding director of the National Theatre School. He received numerous honours for his work, including Officer of the Order of Canada (1977).

Ontario Heritage Trust, an agency of the Government of Ontario

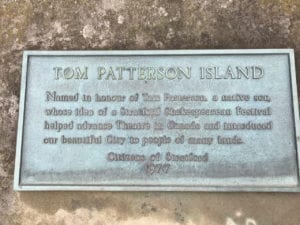

Tom Patterson Island

Named in honour of Tom Patterson, a native son, whose idea of a Stratford Shakespearean Festival helped advance Theatre in Canada and introduced our beautiful City to people of many lands.

Citizens of Stratford,

1977

Sir John Cunningham McLennan, 1867-1935

An outstanding Canadian scientist, McLennan was born in Ingersol and moved to this house in 1883. He attended the University of Toronto where he later became head of the Physics Department. His research and publications brought international recognition to the University’s physics laboratory, which bears his name.

A leading advocate of close ties between science, industry and government, McLennan was instrumental in the founding of the Advisory Council on Industrial and Scientific Research, later the National Research Council.

His work in England on the magnetic detection of submarines and the use of uranium in the treatment of cancer, his explanation of the yellow-green light in the spectrum of the aurora borealis and his success in liquefying helium, contributed to his world-wide reputation. He was knighted in 1935.

Erected by the Ontario Heritage Foundation, Ministry of Culture and Recreation

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!