Richard J. Evans’s trilogy and related 2015 text offers a valuable historical overview of Nazi Germany

Richard J. Evans’s Nazi Germany trilogy along with The Third Reich in History and Memory (2015) is strongly evidence-based, and is presented within a framework that is well-reasoned and well-informed by the available historiography.

A Jan. 4, 2016 review by Christopher E. Mauriello, Salem State University, of The Third Reich in History and Memory (2015), can be accessed here.

A Nov. 14, 2005 New Yorker mini-review of The Third Reich in Power (2005) can be accessed here.

The two other books in the above-noted trilogy are:

The Coming of the Third Reich (2004)

The Third Reich at War, 1939-1945 (2008)

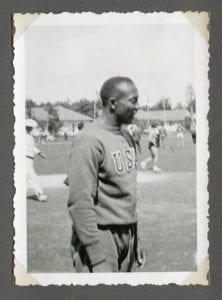

I became interested in the trilogy because I have an interest in reading about – and taking the time to picture in my imagination – events related to my father’s 1936 Berlin Olympics photo album:

Kaljo Pill, age about 21. Detail from 1936 group photo of young athletes from Estonia, who attended the 1936 Berlin Olympics as student observers. Source: Kaljo Pill

Small Arms Society

I also have an interest in the trilogy because it gives me a better understanding, than I would otherwise have, of the history related to the Small Arms Building in Mississauga.

I often think about the fact the Small Arms Building has a direct connection to all of the events associated with the Second World War and the history of events leading up to the war.

I have now read each of the books in the Richard J. Evans trilogy.

Some years ago, I read the third book in the series, but not closely. I read bits and pieces, to familiarize myself with the contents.

Group portrait of athletes, from the University of Tartu in Estonia, who attended the 1936 Berlin Olympics as student observers. The photo was taken, I believe, in 1936 or earlier. Source: Kaljo Pill

After I had spent sone time scanning and studying the photos in the above-noted 1936 Berlin Olympics photo album, I decided that I would read each of the trilogy books closely, from cover to cover. In my reading project, I was planning to proceed chronologically, starting with the first book. However, my Toronto Public Library copy of the first book was all marked up by some previous reader(s), and I decided to start with the second book, which I had borrowed from the library along with the first one.

Thus I read the second book, and requested another copy of the first book from the library. The second copy, of the first book in the trilogy, turned out to be unmarked by previous library patrons. Thus after I had finished the second book in the series, I proceeded to read the first, in the series.

That worked out really well, as it meant I was reading the texts in an active kind of way, which I like to do. Reading in chronological order sometimes also works out fine, but I like to mix up the order, when I can, or when I feel like it, because it means that I have a more active engagement with the text, than otherwise would be the case.

Among other ways that I have learned about reading strategies, I learned a lot about this topic years ago when I worked as an elementary teacher with the Peel District School Board.

Finally, I read the third book, about Nazi Germany at war, and then proceeded with The Third Reich in History and Memory (2015).

I am impressed with the work of Richard J. Evans. Among other things, I have learned about how first-rate professional historians go about their work.

I am particularly impressed with Evans’s preface to The Coming of the Third Reich (2004).

Colonialism

The first chapter in The Third Reich in History and Memory (2015) is concerned with links that have been posited between Germany’s colonial experience and the subsequent history of Nazi Germany. The author reviews a study which provides an excellent overview, with an apt conclusion, regarding this topic.

I have for many years been strongly interested in the topic at hand, for which reason I was delighted when I had the opportunity to read the chapter.

[Please see updates below regarding the theme of colonialism.]

Style of writing

I have read many books about Nazi Germany over the past half-century and more. The studies by Richard J. Evans are among the most valuable studies, in this body of literature, that I have come across.

I have already referred to the quality of the evidence and cogency of the framework within which the evidence is presented.

Also of value is Evans’ capacity to maintain the close attention of the reader, by combining high-quality, well-reasoned analysis while drawing aptly from diaries, anecdotes, and details. Such an approach brings the story to life, in a way that an extended essay is not able to do.

That said, there are potential drawbacks, in cases where the selection of details serves to engage readers through the power – and drawbacks – of stereotypes (in particular as it relates, by way of example, to the topic of stuttering).

Updates

A May 8, 2018 New York Times article is entitled: “Why Are So Many Democracies Breaking Down?”

Also of interest: The Imperial Nation: Citizens and Subjects in the British, French, Spanish, and American Empires (2018). A blurb reads:

Summary

How the legacy of monarchical empires shaped Britain, France, Spain, and the United States as they became liberal entities

Historians view the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as a turning point when imperial monarchies collapsed and modern nations emerged. Treating this pivotal moment as a bridge rather than a break, The Imperial Nation offers a sweeping examination of four of these modern powers–Great Britain, France, Spain, and the United States–and asks how, after the great revolutionary cycle in Europe and America, the history of monarchical empires shaped these new nations. Josep Fradera explores this transition, paying particular attention to the relations between imperial centers and their sovereign territories and the constant and changing distinctions placed between citizens and subjects.

Fradera argues that the essential struggle that lasted from the Seven Years’ War to the twentieth century was over the governance of dispersed and varied peoples: each empire tried to ensure domination through subordinate representation or by denying any representation at all. The most common approach echoed Napoleon’s “special laws,” which allowed France to reinstate slavery in its Caribbean possessions. The Spanish and Portuguese constitutions adopted “specialness” in the 1830s; the United States used comparable guidelines to distinguish between states, territories, and Indian reservations; and the British similarly ruled their dominions and colonies. In all these empires, the mix of indigenous peoples, European-origin populations, slaves and indentured workers, immigrants, and unassimilated social groups led to unequal and hierarchical political relations. Fradera considers not only political and constitutional transformations but also their social underpinnings.

Presenting a fresh perspective on the ways in which nations descended and evolved from and throughout empires, The Imperial Nation highlights the ramifications of this entangled history for the subjects who lived in its shadows.

[End]

A recent post addressing related, relevant themes is entitled:

Nazism and Stalinism: What (if anything) did they have in common?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!