American Racism in the ‘White Frame’ – July 27, 2015 New York Times article

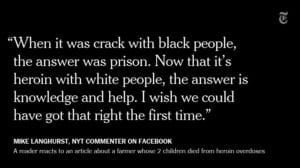

The image – click on it to enlarge it – is from a March 18, 2017 tweet from The New York Times @nytimes reading: Our top 10 comments of the week http://nyti.ms/2nD8BJX

A July 27, 2015 New York Times article is entitled: “American Racism in the ‘White Frame.’ ”

I have thought of adding a link to the above-noted article as an update to previous posts about military history and related topics, including the concept of extremely violent societies.

However, the July 27, 2015 New York Times article warrants a separate post.

Evidence has tremendous value, especially when adequate analytic tools, and an adequate analytic framework, are available

The article features an evidence-based, analytically useful overview of the history of racism in the United States. What it discusses is of relevance outside of the United States also.

“To understand well the realities of American racism,” the article notes, “one must adopt an analytical perspective focused on the what, why and who of the systemic white racism that is central and foundational to this society. Most mainstream social scientists dealing with racism issues have relied heavily on inadequate analytical concepts like prejudice, bias, stereotyping and intolerance. Such concepts are often useful, but were long ago crafted by white social scientists focusing on individual racial and ethnic issues, not on society’s systemic racism. To fully understand racism in the United States, one has to go to the centuries-old counter-system tradition of African-American analysts and other analysts of color who have done the most sustained and penetrating analyses of institutional and systemic racism.”

Updates

A Nov. 12, 2016 Guardian article is entitled: “How to talk to strangers: a guide to bridging what divides us: The more we do to interact with people who aren’t like us, the better off we’ll be in the face of hatred that has become so visible thanks to Donald Trump.”

Also of interest and relevance: White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide (2016)

As well: Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (2016)

A May 25, 2016 Guardian longread article is entitled: “The enduring whiteness of the American media: What three decades in journalism has taught me about the persistence of racism in the US.”

A March 13, 2017 CityLab article is entitled: “Mapping the Achievement Gap: A colorful dot map reveals the stark differences in educational levels across urban and rural areas—as well as the effects of racial segregation within cities.”

A July 26, 2017 Columbia Review of Journalism article is entitled: “Photos reveal media’s softer tone on opioid crisis.”

An Oct. 18, 2016 Guardian article is entitled: “Racial identity is a biological nonsense, says Reith lecturer: Philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah says race and nationality are social inventions being used to cause deadly divisions.”

Also of relevance is a book I learned about from a New York Times article, namely Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (2017).

Summary

How American race law provided a blueprint for Nazi Germany

Nazism triumphed in Germany during the high era of Jim Crow laws in the United States. Did the American regime of racial oppression in any way inspire the Nazis? The unsettling answer is yes. In Hitler’s American Model, James Whitman presents a detailed investigation of the American impact on the notorious Nuremberg Laws, the centerpiece anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi regime. Contrary to those who have insisted that there was no meaningful connection between American and German racial repression, Whitman demonstrates that the Nazis took a real, sustained, significant, and revealing interest in American race policies.

As Whitman shows, the Nuremberg Laws were crafted in an atmosphere of considerable attention to the precedents American race laws had to offer. German praise for American practices, already found in Hitler’s Mein Kampf, was continuous throughout the early 1930s, and the most radical Nazi lawyers were eager advocates of the use of American models. But while Jim Crow segregation was one aspect of American law that appealed to Nazi radicals, it was not the most consequential one. Rather, both American citizenship and antimiscegenation laws proved directly relevant to the two principal Nuremberg Laws–the Citizenship Law and the Blood Law. Whitman looks at the ultimate, ugly irony that when Nazis rejected American practices, it was sometimes not because they found them too enlightened, but too harsh.

Indelibly linking American race laws to the shaping of Nazi policies in Germany, Hitler’s American Model upends understandings of America’s influence on racist practices in the wider world.