Input from Jaan Pill of Preserved Stories regarding Feb. 7, 2017 Long Branch Guidelines Draft

Beach at Marie Curtis Park in Long Branch. The view is from a location to the west of the corner of Lake Promenade and Forty Second St. Jaan Pill photo. Click on the image to enlarge it; click again to enlarge it further.

As a rule, I make it a practice to avoid posting my own input with regard to ongoing public consultations such as the Long Branch Guidelines Draft.

Instead, I just send in my comments and then I forget about it.

My reasoning is that my own views are neither here nor there, in the wider scheme of things, but rather represent just one person’s limited perspective regarding whatever topics are at hand.

That said, sometimes I like to do things differently. For that reason, in this case I’ve decided to actually share (by way of a blog post) the content of my input, in this case in my role as a member of the Long Branch Guidelines Advisory Group, in response to the Feb. 7, 2016 Guidelines Draft.

Who is going to read what follows below, I have no idea.

Jaan Pill

March 3, 2017

Re: Feb. 7, 2017 Guidelines Draft

In these comments, I have covered as much ground as I can, in the time available to me. My major source of reading has been the 13-page Reference Material. I have also read parts of the 90-page document entitled “Long Branch Draft (for discussion purposes only) Neighbourhood Character Guidelines,” and the 67-page page document entitled: “February 7, 2017 Community Advisory Group Meeting: Long Branch Neighbourhood Character Guidelines.”

In the notes below, I mention that the urban planning terminology in the 13-page Reference Material is at times a challenge for me, as a layperson not familiar with architectural terminology, to follow. I want to add that the explanatory language in the 90-page document, and in the 67-page document, is generally much easier to follow.

1. Do you have any suggested refinements to the Character Framework Plan?

*

Part “a”

The Long Branch Character Defining Conditions, in the 13-page document, refer (Part “a”) to “Historic Long Branch houses dating back to original ‘villa’ lots.”

The reference brings to mind a May 22, 2008 insidetoronto.com article entitled: “OMB supports Lake Promenade homeowner: Long Branch house on city’s list of heritage properties for demolition, rebuilding.”

Among the houses that are referred to, in the above-noted article, is 25 Thirty Third St. I’ve been in touch a while back with a former resident of the cottage that was located at the site. The house is on the route of the Walking Tour that was a feature of the Long Branch Guidelines Pilot Project. A new house is now at the site.

The historic cottage that used to exist at 25 Thirty Third St was listed as a heritage property but was torn down anyway.

That is to say, the city’s list of heritage properties does not necessarily carry much weight, albeit designation under the Ontario Heritage Act does.

This is a recurring narrative, from what I can gather. High hopes, dashed.

Part “d”

The Long Branch Character Defining Conditions (in the 13-page document) refer (Part “d”) to “Predominant 40-50’ lot frontage with generous sideyard setbacks which both provide access to the rear of the lot and establish a street rhythm.”

It may also be noted with regard to this topic that, during the Village of Long Branch era, there were also 25’ lots in place in some parts of Long Branch (e.g. in parts of the northwest corner of Long Branch).

After the process by which the Villa of Long Branch was amalgamated to become part of the Borough of Etobicoke, it’s my understanding that these lots were classified as legal nonconforming lots, in the context of the Etobicoke bylaws that were introduced during that particular stage of amalgamation.

A key point here is that a lot of that size (that is, 25’ frontage) had a typical house footprint that featured generous setbacks, as contrasted to a footprint that would take up most of the available space on a current, 25’ severed lot.

Background concerning the overall historical narrative is available at a link at the Preserved Stories website:

Part “h”

Part “h” refers (on page 3 of the 13-page document) to “Consistent front yard setbacks and street walls along North-south streets which serve as important view corridors from the public realm to the waterfront.”

I very much like how the lake views – that is, the view corridors looking south toward Lake Ontario – are indicated (in blue) on the map accompanying the Long Branch Character Framework Plan.

I also like how the full westward reach of Long Branch (with the border along the shoreline extending almost to Applewood Creek) is accurately represented.

An interesting feature of the lake views is that some are unobstructed, whereas the one at the foot of Fortieth Street has some large rocks placed in front of it.

As well, at the view corridor at the foot of Fortieth St., in the past there would have had a Ministry of Transportation checkerboard sign indicating that the road terminates at that point. That sign has been removed.

The presence of the rocks and the absence of the sign demonstrate a degree of encroachment of the view corridor by an adjoining landowner. The land is in a sense being treated as private property, with the expectation that members of the public will steer clear of this lake view.

My own discussions with the adjacent property owner have been cordial, and I have not had a problem in walking to the edge of the view corridor, to admire the view of the lake.

It may be useful to bring attention to encroachments, of the nature that I have described, and to underline the fact that a municipality has a responsibility to ensure that public land remains, clearly and demonstrably, in public hands.

It would also be worthwhile to promote registration of the lake views at the city’s heritage registry, as has been done elsewhere along the lake, as noted at a Preserved Stories blog post entitled:

A selection of lake views are now on the City of Toronto heritage register

Part “i”

I very much like the references to the mature tree canopy, in the document. However, as with many things, including how the Committee of Adjustment and the Ontario Municipal Board operates, the concept that all is working out well with our trees may require some fact-checking, as I will note further along in these notes.

What more could be added to the defining conditions?

As noted below, it may be useful to bring attention to the high water table that is characteristic of Long Branch. This is particularly of relevance given the likelihood that extreme weather events will increase in number and intensity in years ahead as a consequence of climate change.

2. What do you like about the draft Guidelines? How could they be improved? Are there any additional guidelines we should consider?

*

Comments regarding categories

*

3.2 Height & Massing

As a layperson, I had trouble with this item when I first encountered it in the Feb. 7, 2017, 13-page Reference Material document.

Some time later, I referred to a library book, Architecture: Form, Space, & Order, Fourth Ed. (2015) and found a definition of “datum” that enabled me to understand what part of 3.2 Height & Massing was about. I also subsequently noted that “datum” is indeed defined in the 90-page Guidelines document.

I don’t mind learning a new language (in this case architectural jargon), but I think it might be helpful for SvN to devote resources toward development of a “plain English” version of the Reference Material.

A plain English version of the text for 3.2 Height & Massing (and for each of the other categories of texts) could be added as a supplement to the standard version. The standard version is the one that is based on precise, and useful terms, from urban design and architecture. The plain English version would be a translation of such technical terms into everyday language.

Insurance companies and other lines of work sometimes make an effort to produce texts written in plain English. This is a commendable approach to ensuring that people understand what they are reading. Especially in a case like a Guidelines Pilot Project, which involves civic engagement, there is value in ensuring that members of the public have the best possible grasp, of the topics at hand.

In that way, the information would be clearly presented both for urban design professionals and for interested laypersons (who may be professionals, but in lines of work other than urban design and architecture).

Based on anecdotal evidence from what I have observed at Committee of Adjustment and Ontario Municipal Board meetings, it may also be the case that some COA members and OMB adjudicators would also benefit from being able to read plan English versions of such Guidelines, once the point arrives down the road, when the Guidelines would be implemented.

Plain English versions of the Guidelines, in their final form, would also be helpful for residents appearing at COA, OMB, and Toronto Local Appeal Body hearings in the future.

I believe it would be relatively straightforward to find a consultant who could help out with translation of technical terms into plain English. A person with a good track record for writing media releases (which often means a person with wide experience in media writing) would fit the bill perfectly.

A person with a strictly academic background but without experience in writing for media would, on the other hand, not be a good bet at all, in my view, as a reader of a wide range of texts.

I can add that, some years ago I began to write regular news updates, at my website, regarding the Lakeview Waterfront Connection Project and Inspiration Lakeview.

The fact that I have devoted much time and interest to such posts is not of relevance to readers of my current comments, regarding the Long Branch Guidelines Draft.

What may, possibly, be of interest, however, concerns the topic of how I originally became interested in following the Lakeview projects closely, and how I became a regular attendee at meetings connected with them.

What inspired my interest was simply the quality of the communications, directed toward residents in Mississauga, connected with the above-noted projects. The quality of the communications has been consistently first-rate. News releases and online pages are succinct and engaging. Technical information is presented in plain English.

When I come across material that is so exquisitely well written, I pay close attention. I’m aware of how much work and coordination, at an organization-wide level, is involved in the creation of such materials. That is what has inspired me, no question. That’s what prompted me to start writing about these projects, at the Preserved Stories website.

The photos on pages 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13 of the Feb. 7, 2017 Reference Material work really well

For 3.2 Height & Massing, Figures 44, 45, and 46 (photos plus captions plus annotations laid over the photos) work really well in getting across whatever the content of the related Objectives and other texts may be.

3.3 Building Elements

Again, Figures 59, 60, and 61 tell the story very clearly for me. Given that I’ve subsequently figured out what “datum” means, after reading Francis D.K. Ching (2015) as noted above, I also have a better grasp of the Objectives and text for this category than would otherwise have been the case.

3.4 Driveways & Garages

Figures 75, 76, and 77 are very useful. They help me to understand what the Objectives and text (p. 8 of the Reference Material, handed out at Feb. 7. 2017 Advisory Group meeting) are about.

3.5 Setbacks & Landscape

I’m at a loss with regard to Figures 79, 80, and 81 because the captions are incomplete. Each says: “Identify image and cite your source.” That said, the annotations over the photos tell the story quite well.

3.6 Special Features

The Objectives and accompanying text on p. 12 of the Reference Material is very clear, and relatively free of jargon.

The references to trees are inspiring – but in the context of what has been observed in recent years in Long Branch, is to a large extent (I regret to say this) meaningless. That is to say, taking the final version of the Guidelines and using them to save some of the tree canopy in Long Branch would be feasible, I like to think, but it would be a major challenge, given the situation that is currently in place, as observed by long-time residents.

In my experience, as things currently stand members of the current Committee of Adjustment would care less about trees, and City of Toronto staff appear to have minimal impact on whether or not there are trees in place in Long Branch or not. There is a contrast between the protections that are in place, on paper, and what actually happens on the ground, from one week to the next.

Photos on page 13 are highly effective and informative

On a positive note, and forgetting about the trees, the photos in Figures 84 to 89 are very helpful. I very much like the reference to hardscaping at 20 & 22 James St. at Thirty Seventh St.

I would add that it would be useful to extend the dotted line to the back of the two houses, as the backyard space of the two buildings also features extensive hardscaping, as is noted in a blog post (with accompanying photos) at the Preserved Stories website:

Sump pump working really hard, at new 22 James St. severed-lot building in Long Branch

*

Are there any additional guidelines that warrant consideration?

*

A suggested addition to 3.6 Special Features

I might be useful for the Guidelines to address the fact that Long Branch has a high water table. That is, it would be useful if the Guidelines were to take that aspect of the physiography of Long Branch into account.

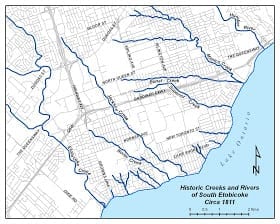

A general overview of the topic is provided by a Lost Creeks of South Etobicoke webpage set up by Michael Harrison, who has a longstanding reputation for provision of accurate and balanced information regarding local physiography and history. The map below is from the above-noted webpage.

In some cases (I am not aware of definitive, scientific evidence, however, so I am just sharing anecdotal evidence) there may be smaller, undocumented underground streams in parts of Long Branch that can give rise to consistent and unremitting stormwater problems.

I’ve heard (again, anecdotally speaking) of a number of cases of basement flooding in new builds across the community. In one case, it was as a result of power going off during an extreme weather event. In such a case, the solution is a backup generator.

In other cases, a more powerful sump pump and in some cases even a larger-diameter outflow hose, permitting more outflow per minute, is the solution – although the next issue is where does the water go on discharge. One of the best solutions is at a house that I know of on Forty Second St. facing Marie Curtis Park. It has no basement.

Getting information about water drainage and the like would be a huge challenge, in the event that the Guidelines were to discuss such topics. It’s my understanding, in this regard, based on anecdotal evidence, that questions related to stormwater runoff and drainage are of no interest whatever to members of the current Committee of Adjustment. They would care less.

A City of Toronto webpage is also of relevance: Toronto Maps v2.

According to the map, there are a number of properties on Forty First and Forty Second Streets that are within the Fill Control Line/Flood Line that would, as I understand, require TRCA approval in order for a build to proceed.

You can, it has been noted, see these on the Toronto Maps site by clicking on the “TRCA Regulation Limit” on the map. I have not been able to follow the procedure mentioned in the previous sentence, but have been able to access what may be the same information, by clicking on “Natural Heritage System” on the Legend part of the map.

Suggestions for the approach / format for the public meeting

I did not attend the initial public meeting for the Guidelines Pilot Project. I became interested in the Pilot Project, however, when a fellow Long Branch resident (Brian Liberty, Interim Chairperson of the Long Branch Neighbourhood Association) asked if I would be attending the Walking Tour that was announced some time after the initial public meeting.

I made inquiries regarding the Walking Tour and learned it was restricted to members of the Advisory Group and City of Toronto staff. My inquiries had the result, however, that after the Walking Tour, which I did not attend, I was able to become a member of the Advisory Group.

My attendance at the Feb. 7, 2017 meeting was my first contact with the SvN and City of Toronto staff involved with the Pilot Project. I was impressed with the quality of the information that was shared at the meeting.

In the course of discussions, I shared the thought that having a microphone and speaker system at the public meeting, what would follow the Feb. 7, 2017 meeting, would be a great idea.

For a smaller meeting like the Feb. 7, 2017 event, a good portable speaker system can also make a huge difference, in my experience, in ensuring that each person in the audience – including those whose hearing is not perfect, and including those sitting at the very back of a group of people – can hear, without straining, each word.

During the past five years, I’ve been involved in leading and/or organizing many Jane’s Walks in Toronto and Mississauga. I use a Taynor TVM10 portable amplifier and a wired microphone, purchased from Long & McQuade, to ensure that every person attending such a walk hears every word.

In other circumstances, I might be inclined to use a couple of such portable amplifiers, connected to a single mic. I might also be inclined to use a couple of wireless mics in place of wired mics, so that comments from the audience can be amplified, such as during a Q & A.

As it is, for Jane’s Walks and similar events, I like to use a wired mic because it’s a foolproof and totally uncomplicated way to work. In a Jane’s Walk, anybody on the walk can walk up to the mic, in order to speak to the group as a whole; there is no pressing need to arrange for a wireless mic.

Attitudes about the usefulness of a mic in at a meeting falls into three categories of receptivity, with regard to comments from me regarding the usefulness of sound amplification in particular circumstances:

a) Some people are used to using mics at meetings and use them as a matter of course;

b) Some people will use a mic if the concept, that it’s good to ensure that every person hears every word, is explained to them;

c) Some people are convinced that their voices and lungs are sufficiently powerful that the use of a mic is totally out of the question, under any circumstances, no matter what the size of the audience, and no matter what the ambient noise levels may be. People in the latter category are also likely to believe that if people at the back can’t readily hear them, or only hear bits and pieces of what is being said, that is of no concern to anybody.

In terms of format, as I have mentioned, I do not know what the format was, for the initial Guidelines public meeting. In general terms, I have the sense that organizers of such meetings often make a point of having people break into smaller groups to discuss a specified list of questions, after which a spokesperson from each group reports to the meeting as a whole.

The intent of such an arrangement is to ensure that each person at a meeting has the opportunity to offer input, instead of having a situation where one or a handful of vocal individuals monopolize the available speaking time, and everybody sits and listens (not patiently) while the minority of the most voluble and opinionated speakers, from the assembly of attendees, carry forth, non-stop.

The Feb. 7, 2017 Advisory Group meeting was exquisitely well organized. The format ensured that each person at the meeting had the opportunity to offer meaningful input. There was at least one facilitator at each group, who was taking notes and helping people stay on track. There was a list of specific questions to focus upon. Spokespeople, presenting on behalf of each table, were advised to keep to two or three key points.

I have in recent years attended many meetings in Mississauga concerned with the Lakeview Waterfront Connection Project and Inspiration Lakeview. I would like to suggest that people connected with these two projects might be great people to compare notes with.

The logistics associated with public consultations at such meetings are, as was the case with the Feb. 7, 2017 Guidelines meeting that I attended, well planned and well thought out. There is a great feeling of energy and enthusiasm in the air. People are aware that their input is a key feature of all of the ongoing work.

Among the key people, who would be great to compare notes with, about the organizing of such meetings, and who can offer names of other people to speak with, is:

Kate Hayes, Manager, Ecosystem Restoration Management, Watershed Transformation – Credit Valley Conservation:

khayes@creditvalleyca.ca

Kate Hayes is also familiar with the communications strategies associated with the Lakeview Waterfront Connection Project and with Inspiration Lakeview.

Another person, who is highly knowledgeable, with reference to communications strategies and civic engagement connected with the above-noted project, is City of Mississauga Ward 1 Councillor Jim Tovey:

Jim.Tovey@mississauga.ca

General comments

The following comments concern thoughts that have occurred to me, following the Feb. 7, 2017 Advisory Group meeting. Since the meeting, and in some cases prior to it, I’ve been reading about architectural terminology, history, theory, and related topics.

Below are a very small number of highlights from what I have learned.

Reinhabitation of the house through narrative

In speaking about Long Branch over the years, we are in a sense speaking of reinhabitation through narrative.

The Oxford Dictionary defines reinhabitation as: The action or an instance of reinhabiting a place.

Reinhabitation is a re-occurring phenomenon. In Long Branch, as in any local community, we need not speak of buildings simply as architectural artifacts.

We can, that is, also speak of the generations of people who reinhabit a given assortment of the lots on which the houses of Long Branch have been built, and in some cases are being rebuilt. People inhabit a given space for a given period of time. Then they move away or pass away, and a new generation lives at the property. A continuous process of reinhabitation occurs.

I came across this concept in a 1994 paper by Annmarie Adams and Pieter Sijpkes of McGill University. The paper is entitled: Wartime housing and architectural change, 1942-92.

It is included in a 1995 issue of Ethnologies, from the University of Laval, Quebec, devoted to Vernacular Architecture.

The research methodology that Annmarie Adams and Pieter Sijpkes have adopted is of interest:

“Our study offers no typology of architectural change; at least three other studies of wartime housing in Canada have fulfilled that objective. We focus, rather, on a smaller sample (25 case studies) in much more depth and employ methods more commonly used in the fields of anthropology, cultural geography, and folklore than in traditional architectural research. Instead of focusing on formal analysis, that is, this project assumes architecture as a dynamic process and grants building users agency in the shaping of their own spaces. Architecture as imagined or constructed by its designers is only a starting point for such analyses.

“Folklorist Michael Ann Williams has described this methodology (particularly the use of oral testimony) in the study of domestic space as a ‘reinhabitation of the house through narrative’ and has suggested that the richness of this case-study approach may call into question the usefulness of studying buildings as artifacts. Following this thinking, we hope our research contributes to a growing understanding of the do-it-yourself home improvement industry in Canada, and, more generally, to the study of vernacular architecture.”

Homeplace: The Making of the Canadian Dwelling Over Three Centuries (1998)

Peter Ennals and Deryck W. Holdsworth, authors of Homeplace: The Making of the Canadian Dwelling Over Three Centuries (1998), adopt a perspective similar to that of Annmarie Adams and Pieter Sijpkes (1998).

The authors of Homeplace (1998) speak (p. xiii) of rejecting “façadism – the interpretation that limits itself to the view from the street alone.”

The first chapter addresses (p. 6) frameworks for the study of Canadian shelter.

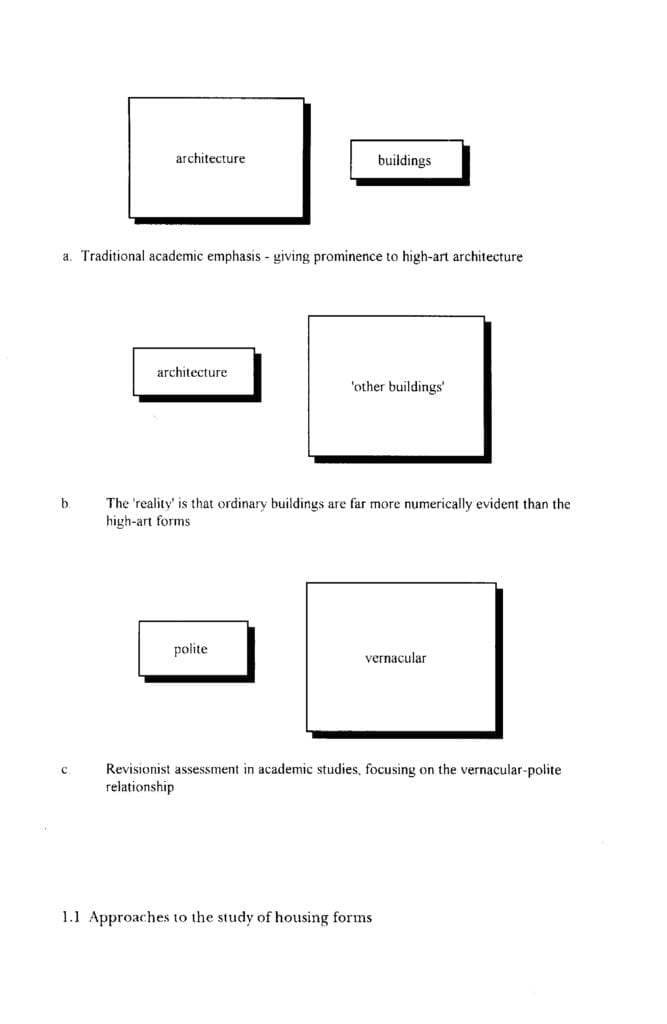

That is, they speak of three possible approaches to the study of housing forms:

a) a traditional academic emphasis giving prominence to high-art architecture;

b) an emphasis that acknowledges that the reality is that ordinary buildings are more “numerically evident” than the high-art forms; and

c) a revisionist assessment in academic studies, focusing on what the authors terms “the vernacular-polite relationship.”

These approaches, from the two above-mentioned studies, are useful in enabling a layperson such as myself to picture, in a better way than I otherwise would be able to do, the contents of the Feb. 7, 2017 Long Branch Guidelines Draft.

Conservation for Cities (2015)

The Guidelines Draft gives me some (small) measure of confidence that studies such as Conservation for Cities: How to Plan and Build Natural Infrastructure (2015) may include material that may be of relevance with regard to my understanding of next steps for Long Branch.

I’m very much aware that such principles are at play in the development of the Mississauga waterfront, through the Inspiration Lakeview project, which I’ve been following (with enthusiasm) through posts at the Preserved Stories website in recent years.

The Conservation for Cities (2015) study speaks of cities using green infrastructure to mitigate stormwater. In a description of work in Washington, D.C., the study notes (p. 67) that:

“Wetlands and other constructed natural habitats can slow the flow of stormwater and increase infiltration into the subsurface. Natural infrastructure also acts as a filter, reducing concentrations of some pollutants. In essence the city is restoring bits and pieces of the ecosystem that once was there, so they can receive its stormwater mitigation benefits.”

There’s always the chance that Long Branch will move in future toward such ways of addressing stormwater and related issues.

Updates

Also of interest:

Going Public: A Guide for Social Scientists (2017).

A Feb. 28, 2017 Cochrane Community article is entitled: “Results and conclusions of the CEU’s Plain Language Summary pilot project.”

The article underlines the value of plain English, evidence, and evidence-based practice.

A May 6, 2016 Cochrane Review article, entitled “Fixed-dose combination therapy for the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,” demonstrates how a typical plain language summary enables non-technical readers to readily comprehend a technical (in his case medical) report.

[End of updates]

Conclusion

The Feb. 7, 2017 Advisory Group meeting has prompted me to study the language of urban design, so that I can comprehend the contents of the Feb. 7, 2017 Guidelines Draft. It has also prompted me to focus, as an upcoming project, on sharing at the Preserved Stories website some narratives based on what actually occurs at Committee of Adjustment meetings. What occurs at such meetings is part of a larger story, of which the Guidelines is a part.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!