When Britain burned the White House

I have an interest in military history including the history of the British empire.

My interest in the latter empire stems from the fact that Colonel Samuel Smith, who fought on the British side in the American Revolutionary War, in 1797 built a log cabin a one-minute walk from where I live in Long Branch (Toronto not New Jersey).

Battle of Crysler’s Farm

View of Battle of Crysler’s Farm national historical site, looking south toward the St. Lawrence Seaway. The battlefield vanished in 1958 when the area was flooded during the building of the Seaway. Jaan Pill photo

This summer (2014) I visited the site of the Battle of Crysler’s Farm, located west of Cornwall on the way to Kingston along the former No. 2 Highway which in this part of Ontario runs south of Highway 401 along a route that takes it close to the St. Lawrence Seaway.

When travelling toward Toronto from Quebec I usually drive along Highway 401 but on a day in mid-August 2014, I got off the 401 and began driving along the old No. 2 Highway. I came across the Battle of Crysler’s site quite by accident. I noticed a sign and slowed down to have a look.

Crysler not Chrysler

To my recollection, I never learned about the Battle of Crysler’s Farm and the Battle of Chateauguay when I was in school. As a student, I was well acquainted with the storylines of a standardized American version of North American history.

The fashioning of storylines occurs in every country including Canada.

A delightful feature of Canadian history, however, is that it’s generally not a tremendous source of excitement for Canadians. If we stumble across a historic site, that’s great. If we don’t, it’s not a big deal.

I had visited the Crysler site about a decade earlier but had forgotten about it until I was reminded of the earlier visit.

It was of interest to learn something on the more recent visit about the past, which remains a significant feature of the present moment, as a character in a novel by William Faulkner (see link at the start of this sentence) has remarked.

It took me a while to realize it’s “Crysler” not “Chrysler.”

The Battle of Crysler’s Farm on Nov. 11, 1813 – along with the Battle of Chateauguay on Oct, 26, 1813 – was a crucial battle in the War of 1812.

The battles marked the end of the American effort to conquer Canada.

Additional details about the Crysler battle can be found at another post.

Francophone soldiers played a significant role at the 1813 battles that saved Canada

An overview of the battle notes:

“[Lieutenant-Colonal Joseph Wanton] Morrison’s victory was paid for in blood. His ‘corps of observation’ suffered 200 casualties, or about one-sixth of his total force. The greatest percentage of casualties was taken by the Canadian Fencibles, a regiment raised in Quebec and whose ranks were about 50 per cent francophone. They suffered a casualty rate of nearly 33 per cent. Of note is the fact that of the 270 Canadian regulars under Morrison’s command that day two-thirds were French-speaking soldiers from Quebec.

“Stunned by the ferocity of the Anglo-Canadian army and their Mohawk allies, Wilkinson’s broken and dispirited army went into winter quarters at French Mills (present day Fort Covington), ending the threat to Canada.”

[End of excerpt. I’ve corrected a typo concerned with the spelling of Morrison.]

At Chateauguay, a military force of just over 300 British-led Canadiens defeated a force of at least 3,000 American troops

As I have noted at another post, this battle, combined with the defeat of another invading army at Chateauguay on October 26, saved Canada from conquest in 1813. The Battle of Chateauguay is described in Field of Glory: The Battle of Crysler’s Farm, 1813 (1999).

In that account, Donald E. Graves notes (p. 110) that the Battle of Chateauguay was “a clear demonstration of how a well-led and positioned military force can hold off an opponent vastly superior in numbers. In the final analysis, just over three hundred Canadiens led by [Charles] de Salaberry, with the support of [George] Macdonell, had beaten off an attack by at least three thousand American troops who came into action. It was not a question of courage, for courage was lacking on neither side; it was a question of leadership, and the fumbling and hesitant decisions and movements of [Wade] Hampton and [Robert] Purdy compare badly with the confident and sure decisions of the two British commanders.”

First Nations warriors played a significant role in the War of 1812

First Nations warriors supporting the British side contributed to the outcome of the Battle of Chateauguay and the Battle of Crysler’s Farm – and to the outcome of the War of 1812. It may be added that when the war was over, the December 24, 1814 Treat of Ghent, as Peter Snow (2013, p. 231) notes, “effectively left each side where it had been before the war began.” The exception was the First Nations side, which lost out.

At Crylser’s Farm, a British military force of 800 defeated an American force of 4,000

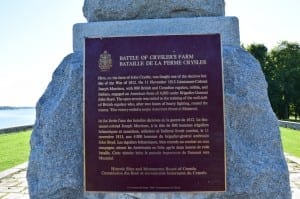

A plaque at the site, provided by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada (Commission des lieux et monuments historiques du Canada) notes that on Nov. 11, 1813, Joseph Morrison, with 800 British and Canadian regulars, militia, and First Nations warriors, engaged an American force of 4,000 under Brigadier-General John Boyd.

The plaque reads: “Here, on the farm of John Crysler, was fought one of the decisive battles of the War of 1812. On 11 November 1813 Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Morrison, with 800 British and Canadian regulars, militia, and [First Nations warriors], engaged an American force of 4,000 under Brigadier-General John Boyd. The open terrain was suited to the training of the well-drilled British regulars who, after two hours of heavy fighting, routed the enemy. This victory ended a major American thrust at Montreal.”

I have read other, slightly different, figures for the sizes of the opposing forces.

Field of Glory: The Battle of Crysler’s Farm, 1813 (1999) by Donald E. Graves describes the battle in detail. He also describes how the British military maintained discipline – through floggings and military executions by firing squad, among other practices.

Also of interest is an event that occurred later in the War of 1812, namely the British burning of Washington, D.C. in retaliation for the American burning of York (now Toronto) in 1813.

When Britain Burned the White House: The 1814 Invasion of Washington (2013)

The blurb for When Britain Burned the White House: The 1814 Invasion of Washington (2013), at the Toronto Public Library website, which also features a separate book review, reads:

“Summary

“As heard on BBC Radio 4’s Book of the Week.

“Shortlisted for the Paddy Power Political History Book of the Year Award 2014.

“In August 1814 the United States’ army is defeated in battle by an invading force just outside Washington DC. The US president and his wife have just enough time to pack their belongings and escape from the White House before the enemy enters. The invaders tuck into the dinner they find still sitting on the dining-room table and then set fire to the place.

“9/11 was not the first time the heartland of the United States was struck a devastating blow by outsiders. Two centuries earlier, Britain – now America’s close friend, then its bitterest enemy – set Washington ablaze before turning its sights to Baltimore.

“In his compelling narrative style, Peter Snow recounts the fast-changing fortunes of both sides of this extraordinary confrontation, the outcome of which inspired the writing of the ‘Star-Spangled Banner’, America’s national anthem. Using a wealth of material including eyewitness accounts, he also describes the colourful personalities on both sides of these spectacular events: Britain’s fiery Admiral Cockburn, the cautious but immensely popular army commander Robert Ross, and sharp-eyed diarists James Scott and George Gleig. On the American side: beleaguered President James Madison, whose young nation is fighting the world’s foremost military power, his wife Dolley, a model of courage and determination, military heroes such as Joshua Barney and Sam Smith, and flawed incompetents like Army Chief William Winder and War Secretary John Armstrong.

“When Britain Burned the White House highlights this unparalleled moment in American history, its far-reaching consequences for both sides and Britain’s and America’s decision never again to fight each other.”

[End of text from Toronto Public Library website.]

Death at Snake Hill: Secrets from a War of 1812 Cemetery (1993)

A book about an archaeological dig, Death at Snake Hill: Secrets from a War of 1812 Cemetery (1993), provides an overview of how the War of 1812 was experienced by soldiers on both sides. I have found the book, and a talk based upon it by Ron Williamson, tremendously informative. It gave me a sense of what the war was like, from the perspective of the individual soldier. A Toronto Public Library website blurb for the study reads:

- In 1987, archaeologists working on a number of waterfront lots in Fort Erie, Ontario, discovered bones that turned out to be the remains of soldiers who had died during the American occupation of Fort Erie 173 years before. They had uncovered a U.S. military graveyard from the War of 1812.

- The archaeological dig that followed attracted great public interest and media attention on both sides of the border. Historical research and scientific analysis of the bones combined to produce a remarkably detailed profile of anonymous victims in a half-forgotten conflict. The Snake Hill story culminated in a remarkable repatriation ceremony in which twenty-eight American soldiers were returned to their homeland for an honorary reburial.

[End of excerpt]

A review for the book can be accessed here.

The book is also highlighted in an overview of War of 1812 studies which can be accessed here.

Waterloo: June 18, 1815: The Battle for Modern Europe (2005)

A useful resource, which helps to place the War of 1812 into a wider context, is Waterloo: June 18, 1815: The Battle for Modern Europe (2005).

Canadians and Their Pasts (2013)

My visit to the site of the Battle of Crysler’s Farm has prompted me to think about a passage in Canadians and Their Pasts (2013), which I’ve noted at a previous post:

I found of interest the following passage (pp. 157-158; I’ve broken the longer text into shorter paragraphs) from the book:

- The survey showed that many Canadians, particularly those with more schooling, viewed the stories conveyed by textbooks and teachers, family and friends, museums and monuments as being open to interpretation, challenge, and critique.

- Their expressed interest in “multiple sources,” “primary sources,” “archives,” and “the real thing” (i.e., artefacts) suggested that they could wield the tools necessary to interrogate claims about the past; they could use evidence to assess contending historical interpretations.

- As a twenty-first-century democratic state, Canada should promote precisely such critical historical practices. Our strategy should be to encourage citizens’ engagement in active interrogations.

Updates

An April 15, 2016 Globe and Mail article by Bob Rae is entitled: “Attawapiskat is not alone: Suicide crisis is national problem.”

A Jan. 23, 2017 article at earlycanadianhistory.ca is entitled: “Anishinaabeg in the War of 1812: More than Tecumseh and his Indians.”

A June 8, 2018 CBC article (which I found was somewhat convoluted, which is apt, as such a level of convolution is in keeping with the topic at hand) is entitled: “Trump blames Canada for torching White House. Meet the ‘reluctant arsonist’: Did Donald Trump get the War of 1812 wrong? Historians say yes, but a Halifax graveyard suggests another story.”

Also of interest is a link at the Brock University website:

Websites for War of 1812 Research

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!