Diversity is for white people: The big lie behind a well-intended word – Oct. 26, 2015 Salon article

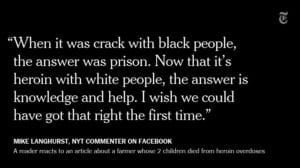

The image – click on it to enlarge it – is from a March 18, 2017 tweet from The New York Times @nytimes reading: Our top 10 comments of the week http://nyti.ms/2nD8BJX

An Oct. 26, 2015 Salon article is entitled: “Diversity is for white people: The big lie behind a well-intended word: ‘Diversity’ sounds polite and hopeful. It’s how we talk when we can’t talk about race, or when whites get nervous.”

The opening paragraphs read:

Our country is convulsing over the issues of diversity and race. Police departments from Baltimore to Minneapolis are talking about diversity hiring as the antidote to anti-black police brutality. Last month’s flash point was Hollywood darling Matt Damon whitesplaining diversity, igniting a Twitterstorm of outrage. Earlier this year was the failed Race Together stunt by the CEO of Starbucks, which tried to enlist customers in over-the-counter exchanges about America’s most vexing dilemma.

As an academic, I have spent more than a decade investigating this enigmatic term: What do we mean by “diversity” and what do we accomplish when we make it our goal? Using first-hand ethnographic observation and historical documents, my research has taken me from the U.S. Supreme Court during debates about affirmative action to a gentrifying Chicago neighborhood to the halls of a Fortune 500 global corporation.

Here’s what I’ve learned: diversity is how we talk about race when we can’t talk about race. It has become a stand-in when open discussion of race is too controversial or — let’s be frank — when white people find the topic of race uncomfortable. Diversity seems polite, positive, hopeful. Who is willing to say they don’t value diversity? One national survey found that more than 90 percent of respondents said they valued diversity in their communities and friendships.

[End of excerpt]

Comment: Social infrastructure of stereotyping, hatred, and bigotry

Some previous posts at this website are entitled:

Fascism and the Italians of Montreal: An Oral History: 1922-1945 (1998)

American Racism in the ‘White Frame’ – July 27, 2015 New York Times article

Erving Goffman’s “total institutions” warrant inclusion in a comprehensive theory of management

Mindfulness meditation – The concept of Buddhist violence (that is, most religions including Buddhism have a propensity toward violence, in particular circumstances)

Frames and framing drive outcomes

Cuddy et al. (2008) outline an evidence-based social infrastructure for stereotyping, bias, and prejudice – in short, the authors provide an overview of how bigotry works in our lives.

Power, competitiveness, and advancement

I would say, based on a reading of the research and theoretical models highlighted by Cuddy et al. (2008), that collaboration, cooperation, competition, and warfare, as well as practices of dismissive comments and words of support, bullying, inclusion, exclusion, and genocide, can all serve – and often do serve – to operationalize the social infrastructure of stereotyping, depending upon the circumstances.

The above-noted study by Cuddy et al. (2008) does not seek to outline ways in which stereotyping can be addressed – or should be addressed – although on occasion it notes that the evidence does not back up a specified instance of stereotyping. Dealing with stereotyping by way of countering its effects is not the point of the paper.

However, in a brief article (Cuddy 2009 as outlined in a previous post), Cuddy addresses ways in which a person can avoid being guided by stereotypes (and thus losing one’s way) when making business decisions.

Other studies by other researchers also address approaches whereby the advancement of ways of behaving, that are not built upon stereotyping, can be implemented.

Military history, propaganda, and public relations

A more recent, 2015 study by Cuddy, also described at a previous post, concerns how to enhance power, competitiveness, and advancement in one’s personal life and career.

Power can be used for good or for ill as military history and the history of policing demonstrate.

Warfare involves the operationalization of the social infrastructure – or social architecture – of stereotyping, bigotry, and hatred.

With regard to warfare and related concepts such as structural violence, useful insights can be obtained from the study of propaganda and public relations (whether used for good or for ill).

With regard to the latter points, previous posts come to mind:

Erving Goffman began his graduate work in Chicago in 1945

The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001)

Backstories related to public relations in the United States and China

Updates

A Nov. 12, 2016 Guardian article is entitled: “How to talk to strangers: a guide to bridging what divides us: The more we do to interact with people who aren’t like us, the better off we’ll be in the face of hatred that has become so visible thanks to Donald Trump.”

In a Nov. 15, 2015 tweet, Amy Cuddy writes: “An outstanding review of the efficacy of diversity trainings, from 178 papers, including practical recommendations.”:

Academy of Management Learning & Education, 2012, Vol. 11, No. 2, 207–227.

Reviewing Diversity Training: Where We Have Been and Where We Should Go

Also of interest and relevance: White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide (2016)

As well: Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (2016)

A May 25, 2016 Guardian longread article is entitled: “The enduring whiteness of the American media: What three decades in journalism has taught me about the persistence of racism in the US.”

A Feb. 27, 2017 Guardian article is entitled: “What’s the best way to create a diverse workplace? Ditch diversity programmes: Firms like Google are as white and male as ever despite costly initiatives. A shift to corporate empathy, taking ‘otherness’ out of the equation, can bring change.”

A March 13, 2017 CityLab article is entitled: “Mapping the Achievement Gap: A colorful dot map reveals the stark differences in educational levels across urban and rural areas—as well as the effects of racial segregation within cities.”

Also of relevance is a book I learned about from a New York Times article, namely Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (2017).

A July 26, 2017 Columbia Review of Journalism article is entitled: “Photos reveal media’s softer tone on opioid crisis.”

Richard Rorty

A July 2017 Los Angeles Review of Books article is entitled: “Conversational Philosophy: A Forum on Richard Rorty.”

The introduction reads:

AFTER DONALD J. TRUMP was elected president of the United States, the American philosopher Richard Rorty (1931–2007) returned to the pages of many of the major newspapers of the world as one of the few thinkers who had predicted the election of a “strongman” with Trump’s homophobic and racist features. The relevant passage can be found in the lectures Rorty delivered on the history of leftist thought in 20th-century America at Harvard University in 1997, and published as Achieving Our Country a year later. While reprints of this book were hitting several political philosophy best seller lists, Rorty’s Page-Barbour lectures — titled Philosophy as Poetry — were also released. If in Achieving Our Country, Rorty predicted the election of a right-wing populist, in the latter he stresses how valuable the imagination is for the future of philosophy, which is, in many ways, an imperiled discipline. Although these are not his most important books, they indicate that Rorty was a philosopher ahead of his time, a philosopher for the future.

The goal of this forum is not simply to remember Rorty 10 years after he passed away on the June 8, 2007, but also to continue the conversation which he urged all philosophers to pursue. I have invited Marianne Janack, María Pía Lara, Eduardo Mendieta, and Martin Woessner to cover specific aspects of Rorty’s thought, including feminism, social hope, and post-truth. Their concise contributions underscore the significance of Rorty’s writings for the 21st century. My introduction recalls important moments of the American thinker’s life as well as his outstanding contribution to continental philosophy.

— Santiago Zabala

An Oct. 18, 2016 Guardian article is entitled: “Racial identity is a biological nonsense, says Reith lecturer: Philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah says race and nationality are social inventions being used to cause deadly divisions.”

In this post, I have referred to a book I learned about from a New York Times article, namely Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (2017).

Summary

How American race law provided a blueprint for Nazi Germany

Nazism triumphed in Germany during the high era of Jim Crow laws in the United States. Did the American regime of racial oppression in any way inspire the Nazis? The unsettling answer is yes. In Hitler’s American Model, James Whitman presents a detailed investigation of the American impact on the notorious Nuremberg Laws, the centerpiece anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi regime. Contrary to those who have insisted that there was no meaningful connection between American and German racial repression, Whitman demonstrates that the Nazis took a real, sustained, significant, and revealing interest in American race policies.

As Whitman shows, the Nuremberg Laws were crafted in an atmosphere of considerable attention to the precedents American race laws had to offer. German praise for American practices, already found in Hitler’s Mein Kampf, was continuous throughout the early 1930s, and the most radical Nazi lawyers were eager advocates of the use of American models. But while Jim Crow segregation was one aspect of American law that appealed to Nazi radicals, it was not the most consequential one. Rather, both American citizenship and antimiscegenation laws proved directly relevant to the two principal Nuremberg Laws–the Citizenship Law and the Blood Law. Whitman looks at the ultimate, ugly irony that when Nazis rejected American practices, it was sometimes not because they found them too enlightened, but too harsh.

Indelibly linking American race laws to the shaping of Nazi policies in Germany, Hitler’s American Model upends understandings of America’s influence on racist practices in the wider world.