Narcoland (2013) describes a disastrous “war on drugs” that has led to more than 80,000 deaths in Mexico since its inception in 2006

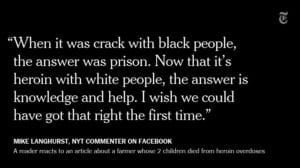

The image – click on it to enlarge it – is from a March 18, 2017 tweet from The New York Times @nytimes reading: Our top 10 comments of the week http://nyti.ms/2nD8BJX

Over the years, I’ve written several posts about the War on Drugs.

One post, by way of example, is entitled:

The Drug Wars in America, 1940-1973 (Kathleen J. Frydl, 2013)

A key point in the above-noted study is that national drug laws have to do with power. It has to do with the assertion, enactment, and demonstration of power.

With regard to these topics, a Feb. 1, 2017 Quartz article is entitled: “Duterte’s war on drugs has created ‘an economy of murder’ in the Philippines, says Amnesty International

A Feb. 2, 2017 New Republic article is entitled: “It Happened to Her: Why is Cat Marnell’s drug memoir so gripping?”

Film noir

When we discuss power, drugs, borders, murders, and incarcerations, we are dealing with storytelling, and with narrative arcs. We are dealing with gangster novels, film noir, and television entertainment. The CBC TV series Pure comes to mind.

Film Noir is a source of fascination for many people, as a series of lectures in 2017 at the Hot Docs Cinema attests.

With regard to modes of storytelling, an article (date unknown) at the website of the International Documentary Association (IDA) is entitled: “The Message Is the Medium: The Difference between Documentarians and Journalists.”

The article is well worth a read. Also with regard to storytelling, a recent post at the Preserved Stories website is entitled:

In addition to the above-noted three features, storytelling is also about exploring the fact that things may not be as they seem. That is, what is the backstage reality, given that we initially know only the frontstage? How do we separate the fact from the fiction, the rhetoric from the reality? What clues are available, to help us on our way?

The Deadly Life of Logistics (2014) by Deborah Cowen, Geography & Planning, University of Toronto

On Jan. 31, 2017 I came across a CBC article entitled: “Legalizing all drugs would be good for Canada, according to Toronto Liberal MP: Nathaniel Erskine-Smith, Liberal MP, says drug use should be treated as a health matter, not a criminal matter.”

A lot of problems would be solved if all drugs were legalized.

Given that they are not all legalized, many problems ensue. That is the message of the post you are now reading.

Recently I borrowed, from the Mississauga Library System, a study entitled: The Deadly Life of Logistics: Mapping Violence in Global Trade (2014).

The study by Deborah Cowen, which is concerned with the logistics of power in contemporary society, is available as a Circulating book at the Mississauga Library System. At the Toronto Public Library, where I usually borrow books, it’s only available as a Reference resource.

With libraries, different people make different choices, for all manner of reasons, with regard to which books to lend out, and which to keep as Reference, as Non-Circulating resources.

An excerpt from The Deadly Life of Logistics (2014) (pp. 218-219) (I’ve broken the longer paragraphs into shorter ones, for ease of online reading) reads:

How do the political geographies and affective economies of “Move or Die” work alongside those of “just-in-time”? In the UPS campaign, we are told that the love of order and efficiency defines logistics in the human world. This is a biopolitical logistics that enables the economy and so prosperity, vitality, and life itself.

Yet when traced through nonhuman worlds, logistics figures as a necropolitical game of survival; the ethos transforms into move or be killed. On the one hand, the national border is explicitly and deliberately problematized and traversed by both animal and cargo circulations. On the other hand, a new kind of bordering is under way, but this is a species border rather than an immediately territorial one.

Visions of nature’s migrations are deeply entangled in the building of logistical futures and spaces. The “human campaign” lays out important logistical lessons, but it also requires the nonhuman supplement. As Sarah Franklin et al. (2000, 9) suggest, heavy traffic or “borrowings” between global nature and culture is leading to their increasing isomorphism, even as their distinctiveness remains crucial.

Indeed, as Donna Haraway (1989, 139) elaborates so eloquently in the context of Cold War representations of nonhuman bodies, “The media and advertising industries of nuclear culture produce in the bodies of animals – paradigmatic natives and aliens – the reassuring images appropriate to this state of pure war.”

Visions of nature can make stark claims on the social while avoiding directly discussing it, and “Move or Die” is an unspeakably important ethos of logistics space. By talking nature in addition to singing culture, National Geographic and UPS at once invest logistics with a biological imperative and infuse the nonhuman world with market logics.

They herald a future of “Move or Die” where circulation is not simply a social good but a necessity for life, where disruption is a matter of when not if, where the powerful rule by virtue of their natural capacity for force, where borders can be both justified and transgressed, and where distinctions between military and civilian authority have no salience and so can be sidestepped.

[End]

Geographical Imagination (2014)

The above-noted excerpt brings to mind a study entitled Genocide and the Geographical Imagination: Life and Death in Germany, China, and Cambodia (2014).

I have discussed the latter study, along with related studies and concepts, at a post entitled:

I am also reminded of previous posts about a study entitled Soldaten: On Fighting, Killing, and Dying: The Secret World War II Transcripts of German POWs (2012)

I’m reminded, as well, of several previous posts at the Preserved Stories website including:

Erving Goffman’s “total institutions” warrant inclusion in a comprehensive theory of management

The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (1999)

Among previous posts about Soldaten (2013) is one entitled:

Instrumental reason drives climate change; and war is work that soldiers do

Narcoland (2013)

I became interested in Narcoland: The Mexican Drug Lords and their Godfathers, English Language Edition (2013) when I came across a Jan. 20, 2017 New Republic article entitled: “Was El Chapo’s Extradition a Gift to Donald Trump?: Theories abound about the suspicious timing of the drug lord’s extradition. But the real story is the information El Chapo might spill.”

A Nov. 21, 2014 Guardian article is entitled: “Narcoland: The Mexican Drugs Lords and their Godfathers by Anabel Hernández – review: A brave and important book that charts the rise of one of the most successful drugs barons of all time and the shocking cost to Mexico.”

The foreword to Narcoland: The Mexican Drug Lords and their Godfathers, English Language Edition (2013) reads:

Foreword by Roberto Saviano to Narcoland (2013)

[I’ve broken longer paragraphs into shorter ones.]

Anabel Hernández’s Narcoland is essential for understanding the power dynamics inside the Mexican economy – the economy’s deep, often concealed, links with politics. This is a book that exposes how everything in Mexico is implicated in the “narco system.” And yet, Anabel’s work is hard to describe. She doesn’t just write about drug trafficking or drugs or Mexico. Her storytelling becomes a method of revealing an entire world.

Anabel’s writing has a scientific, clear, rigorous, almost martial rhythm. She does not give in to lazy descriptions, nor does she give in to anger or disgust. She is a journalist who never loses focus on the mechanisms of power. Her method makes her a rarity in Mexico, and because of this, her voice is a precious resource.

She wants to know how it was possible that one of the great democracies of America became a narco-democracy. With her investigation of the “first government of change” of Vicente Fox (which brought an end to seventy years of one-party rule under the Partido Revolucionario Institucional), she showed how that “change” was fictitious.

She was one of the first reporters to talk about economic corruption, long before the crisis exploded, and she did that by tracking seemingly endless political expenditures. She could already see the system becoming a black hole of bribes and payoffs. Hernandez was one of the first to talk openly about El Chapa Guzman, and one of the first reporters to talk about El Chapo’s connections to politics. Because of this, she became a target of organized crime and now lives a life filled with danger.

Anabel was threatened in a way that might seem bizarre to those unfamiliar with political intimidation. The secretary of public security in Mexico, Genaro Garcia Luna, declared that Anabel had refused protection. Actually, she had never received any protection offers from the state, nor had she refused them. So the message was ominous and clear.

What they were saying was: We could protect you, we could grant you this protection, but not to defend your words: rather, only if you stop writing. And this invitation won’t come again. Anabel, when put in this corner, demonstrated her courage by saying she didn’t want to die.

The role of the journalist is often a difficult one. Journalists often hate each other, or envy each other. This is perhaps one of the jobs in which these feelings are most common, and it can lead to isolation.

It happened to Anna Politkovskaya after she said she was poisoned while on a flight. Many journalists accused Anna of having made it up, saying that she had become a sort of delirious writer who believed in 007-style poisonings. The honesty of her words became apparent when she was murdered. Anabel said: “I want to live. I do not want to be murdered. I don’t want my name to be added to the list of reporters killed every year in Mexico.” And this is courage. The strong, profound courage that I have always admired.

Narcoland is not only an essential book for anyone willing to look squarely at organized crime today. Narcoland also shows how contemporary capitalism is in no position to renounce the mafia. Because it is not the mafia that has transformed itself into a modern capitalist enterprise – it is capitalism that has transformed itself into a mafia. The rules of drug trafficking that Anabel Hernández describes are also the rules of capitalism. What I appreciate in Anabel is not only her courage – it is this comprehensive view of society that is so rare to find.

The value of Anabel’s work is also, perhaps above all, scientific. She managed to get information that had been held by the CIA. She was the first to collate police investigations in several different countries, and she did that by making use of her inheritance: the stories of journalists who came before her. One example is the case of journalist Manuel Buendia Tellezgiron, who had collected information on the relationship between the CIA and the narcos of Veracruz. He got this information from the Mexican secret service and paid for it with his life.

Anabel also had the courage to ask questions about politicians. And to pose these questions does not mean to defame. Her strength was in questioning how it could have been possible for politics to become so powerless or corrupt, justice so incompetent or reluctant. In a situation like this, asking questions becomes an instrument of freedom. A hypothesis can give us insight into the meaning of clues and force politicians to give answers.

When those answers are not given, when politicians do not deny allegations by providing evidence, one can justly suspect their complicity. In the case, for example, of the escape of El Chapa Guzman, Anabel proved the official version to be false while giving a political interpretation of it: politicians may have released El Chapa because it was convenient for them to do so.

In a country like Mexico, which has a deeply compromised democracy, reporters proposing interpretations like these are acting to save their democracy. It is an attempt to bring responsibility back into politics. While nailing politicians to their responsibilities, Anabel transforms her pages into an instrument for readers – an instrument of democracy.

Narcoland describes a disastrous “war on drugs” that has led to more than 80,000 deaths since its inception in 2006. A war that has been nothing more than a blood battle between feuding fiefdoms. A war between one, often corrupt, part of the state against another corrupt part of the state. Hence the war on drugs has not been a war on criminal cartels, nor did it weaken the strength of the cartels.

On the contrary, it boosted it. The war redistributed money, weapons, and repression – and eventually provoked counterattacks. Counter attacks by a government itself infiltrated by criminal organizations. Add to this the disastrous policies of the United States, which for years has claimed to be challenging drug trafficking in Mexico, with no positive results.

Anabel recounts all of this with the detachment of an analyst, but the pages themselves exude tragedy and drama. The drama of those who know that if things keep going this way, democracy itself will be destroyed, crushed. Anabel Hernández sketches a map for her readers, so they can navigate the state of things today. This is a map for all those who understand that the current economic crisis is not only the result of financial speculation without regulations, but also a total impunity for limitless greed. Anabel describes the geography of a world in which political economy has become criminal economy.

[End]

Updates

Topics of related interest are discussed at a post entitled:

Empathy is great provided that we use it wisely

An April 8, 2017 Washington Post article is entitled: “How Jeff Sessions wants to bring back the war on drugs.”

A May 30, 2017 Brookings article is entitled: “Hooked: Mexico’s violence and U.S. demand for drugs.”

A June 12, 2017 ProPublica article is entitled: “How the U.S. triggered a massacre in Mexico.”

A June 19, 2017 London School of Economics and Political Science article is entitled: “Book Review: Sharing This Walk: An Ethnography of Prison Life and the PCC in Brazil by Karina Biondi.”

A Feb. 2, 2017 Atlantic article is entitled: “Patients Are Ditching Opioid Pills for Weed: Can marijuana help solve the opioid epidemic?”

A Feb. 6, 2017 Guardian article is entitled: “‘We fear soldiers more than gangsters’: El Salvador’s ‘iron fist’ policy turns deadly: State security forces have turned the war on gangs into an extrajudicial siege in Distrito Italia, where young men are being killed indiscriminately with impunity.”